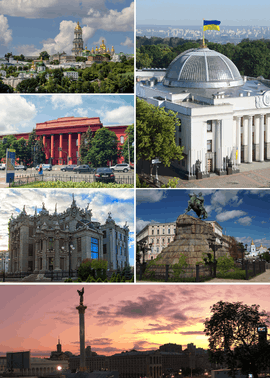

Kiev

Kiev (/ˈkiːɛf, -ɛv/)[7] or Kyiv (Ukrainian: Київ [ˈkɪjiu̯]; Russian: Киев [ˈkʲiɪf]) is the capital and largest city of Ukraine, located in the north central part of the country on the Dnieper River. The population in July 2015 was 2,887,974[4] (though higher estimated numbers have been cited in the press),[8] making Kiev the 7th most populous city in Europe.

Kiev is an important industrial, scientific, educational, and cultural centre of Eastern Europe. It is home to many high-tech industries, higher education institutions and world-famous historical landmarks. The city has an extensive infrastructure and highly developed system of public transport, including the Kiev Metro.

The city's name is said to derive from the name of Kyi, one of its four legendary founders (see Name, below). During its history, Kiev, one of the oldest cities in Eastern Europe, passed through several stages of great prominence and relative obscurity. The city probably existed as a commercial centre as early as the 5th century. A Slavic settlement on the great trade route between Scandinavia and Constantinople, Kiev was a tributary of the Khazars,[9] until seized by the Varangians (Vikings) in the mid-9th century. Under Varangian rule, the city became a capital of the Kievan Rus', the first East Slavic state. Completely destroyed during the Mongol invasion in 1240, the city lost most of its influence for the centuries to come. It was a provincial capital of marginal importance in the outskirts of the territories controlled by its powerful neighbours; first the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, followed by Poland and Russia.[10]

The city prospered again during the Russian Empire's Industrial Revolution in the late 19th century. In 1917, after the Ukrainian National Republic declared independence from the Russian Empire, Kiev became its capital. From 1919 Kiev was an important center of the Armed Forces of South Russia and was controlled by the White Army. From 1921 onwards Kiev was a city of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, which was proclaimed by the Red Army, and, from 1934, Kiev was its capital. During World War II, the city again suffered significant damage, but quickly recovered in the post-war years, remaining the third largest city of the Soviet Union.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and Ukrainian independence in 1991, Kiev remained the capital of Ukraine and experienced a steady migration influx of ethnic Ukrainians from other regions of the country.[11] During the country's transformation to a market economy and electoral democracy, Kiev has continued to be Ukraine's largest and richest city. Kiev's armament-dependent industrial output fell after the Soviet collapse, adversely affecting science and technology. But new sectors of the economy such as services and finance facilitated Kiev's growth in salaries and investment, as well as providing continuous funding for the development of housing and urban infrastructure. Kiev emerged as the most pro-Western region of Ukraine where parties advocating tighter integration with the European Union dominate during elections.[12][13][14][15]

Name

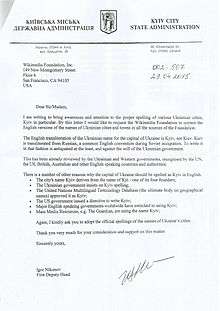

Currently, Kiev is the traditional and most commonly used English name for the city,[16] but in 1995 the Ukrainian government adopted Kyiv as the mandatory romanization for use in legislative and official acts.[17]

As a prominent city with a long history, its English name was subject to gradual evolution. The early English spelling was derived from Old East Slavic form Kyjev (Cyrillic: Къıєвъ[18]). The name is associated with that of Kyi (Кий), the legendary eponymous founder of the city.

Early English sources use various names, including Kiou, Kiow, Kiew, Kiovia. On one of the oldest English maps of the region, Russiae, Moscoviae et Tartariae published by Ortelius (London, 1570) the name of the city is spelled Kiou. On the 1650 map by Guillaume de Beauplan, the name of the city is Kiiow, and the region was named Kÿowia. In the book Travels, by Joseph Marshall (London, 1772), the city is referred to as Kiovia.[19] The name Kiev that started to take hold at later times is based on Russian orthography and pronunciation [ˈkʲijɪf], during a time when Kiev was in the Russian Empire (since 1708, a seat of a governorate).

In English, Kiev was used in print as early as in 1804 in the John Cary's "New map of Europe, from the latest authorities" in "Cary's new universal atlas" published in London. The English travelogue titled New Russia: Journey from Riga to the Crimea by way of Kiev, by Mary Holderness was published in 1823.[20] By 1883, the Oxford English Dictionary included Kiev in a quotation.

Kyiv ([ˈkɪjiw]) is the romanized version of the name of the city used in modern Ukrainian. Following independence in 1991, the Ukrainian government introduced the national rules for transliteration of geographic names from Ukrainian into English. According to the rules, the Ukrainian Київ transliterates into Kyiv. This has established the use of the spelling Kyiv in all official documents issued by the governmental authorities since October 1995. The spelling is used by the United Nations, all English-speaking foreign diplomatic missions,[21] several international organizations,[22] Encarta encyclopedia, and by some media in Ukraine.[23] In October 2006, the United States federal government changed its official spelling of the city name to Kyiv, upon the recommendation of the US Board of Geographic Names.[24] The British government has also started using Kyiv.[25] The alternate romanizations Kyyiv (BGN/PCGN transliteration) and Kyjiv (scholarly) are also in use in English-language atlases. Most major English-language news sources like the BBC,[26] The Economist,[27] and the New York Times[28] continue to prefer Kiev.

History

Kiev is one of the oldest cities of Eastern Europe and has played a pivotal role in the development of the medieval East Slavic civilization as well as in the modern Ukrainian nation.

It is believed that Kiev was founded in the late 9th century (some historians have wrongly referred to as 482 AD).[29] The origin of the city is obscured by legends, one of which tells about a founding-family consisting of a Slavic tribe leader Kyi, the eldest, his brothers Shchek and Khoryv, and also their sister Lybid, who founded the city (The Primary Chronicle). According to it the name Kyiv/Kiev means to "belong to Kyi". Some claim to find reference to the city in Ptolemy’s work as the Metropolity (the 2nd century).[30] Another legend states that Saint Andrew passed through the area and where he erected a cross, a church was built. Also since the Middle Ages an image of the Saint Michael represented the city as well as the duchy.

_painter_The_Hungarian_at_Kiev_(1896-99).jpg)

.jpg)

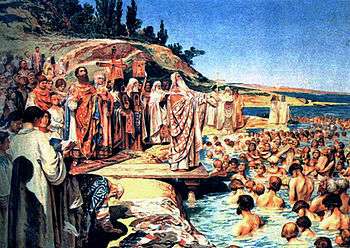

There is little historical evidence pertaining to the period when the city was founded. Scattered Slavic settlements existed in the area from the 6th century, but it is unclear whether any of them later developed into the city. 8th-century fortifications were built upon a Slavic settlement apparently abandoned some decades before. It is still unclear whether these fortifications were built by the Slavs or the Khazars. If it was the Slavic peoples then it is also uncertain when Kiev fell under the rule of the Khazar empire or whether the city was, in fact, founded by the Khazars. The Primary Chronicle (a main source of information about the early history of the area) mentions Slavic Kievans telling Askold and Dir that they live without a local ruler and pay a tribute to the Khazars in an event attributed to the 9th century. At least during the 8th and 9th centuries Kiev functioned as an outpost of the Khazar empire. A hill-fortress, called Sambat (Old Turkic for "High Place") was built to defend the area. At some point during the late 9th or early 10th century Kiev fell under the rule of Varangians (see Askold and Dir, and Oleg of Novgorod) and became the nucleus of the Rus' polity. The date given for Oleg's conquest of the town in the Primary Chronicle is 882, but some historians, such as Omeljan Pritsak and Constantine Zuckerman, dispute this and maintain that Khazar rule continued as late as the 920s (documentary evidence exists to support this assertion – see the Kievian Letter and Schechter Letter.) Other historians suggest that the Magyar tribes ruled the city between 840 and 878, before migrating with some Khazar tribes to Hungary. According to these the building of the fortress of Kiev was finished in 840 by the lead of Keő (Keve), Csák and Geréb, the three brothers, possibly members of the Tarján tribe (the three names are mentioned in the Kiev Chronicle as Kyi, Shchek and Khoryv, none of them are Slavic names and it has been always a hard problem to solve their meaning/origin by Russian historians. Their names were put into the Kiev Chronicle in the 12th century and they were identified as old-Russian mythological heroes).[31]

During the 8th and 9th centuries, Kiev was an outpost of the Khazar empire. However, being located on the historical trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks and starting in the late 9th century or early 10th century, Kiev was ruled by the Varangian nobility and became the nucleus of the Rus' polity, whose 'Golden Age' (11th to early 12th centuries) has from the 19th century become referred to as Kievan Rus'. In 968, the nomadic Pechenegs attacked and then besieged the city.[32] In 1000 AD the city had a population of 45,000.[33] During 1169, Grand Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky sacked Kiev taking many pieces of religious artwork including the Mother of God icon.[34] In 1203 Kiev was captured and burned by Prince Rurik Rostislavich and his Kipchak allies. In the 1230s the city was besieged and ravaged by different Rus' princes several times. In 1240 the Mongol invasion of Rus' led by Batu Khan completely destroyed Kiev,[35] an event that had a profound effect on the future of the city and the East Slavic civilization. At the time of the Mongol destruction, Kiev was reputed as one of the largest cities in the world, with a population exceeding 100,000 in the beginning of the early 12th century.[36][37]

In the early 1320s, a Lithuanian army led by Gediminas defeated a Slavic army led by Stanislav of Kiev at the Battle on the Irpen' River, and conquered the city. The Tatars, who also claimed Kiev, retaliated in 1324–1325, so while Kiev was ruled by a Lithuanian prince, it had to pay a tribute to the Golden Horde. Finally, as a result of the Battle of Blue Waters in 1362, Kiev and surrounding areas were incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania by Algirdas, Grand Duke of Lithuania.[38] In 1482, the Crimean Tatars sacked and burned much of Kiev.[39] In 1569 (Union of Lublin), when the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was established, the Lithuanian-controlled lands of the Kiev region, Podolia, Volhynia, and Podlachia, were transferred from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, and Kiev became the capital of Kiev Voivodeship.[40] In 1658 (Treaty of Hadiach), Kiev was supposed to become the capital of the Duchy of Rus' within the Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth,[41] but the treaty was never ratified to this extent.[42] Kept by the Russian troops since 1654 (Treaty of Pereyaslav), it became a part of the Tsardom of Russia from 1667 on (Truce of Andrusovo) and enjoyed a degree of autonomy. None of the Polish-Russian treaties concerning Kiev have ever been ratified.[43] In the Russian Empire Kiev was a primary Christian centre, attracting pilgrims, and the cradle of many of the empire's most important religious figures, but until the 19th century the city's commercial importance remained marginal.

In 1834, the Saint Vladimir University was established; it is now called the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kiev after the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko. Shevchenko was a field researcher and editor for the geography department.The medical faculty of the Saint Vladimir University has been separated into an independent institution during the Soviet period and is called now Bogomolets National Medical University.

During the 18th and 19th centuries city life was dominated by the Russian military and ecclesiastical authorities; the Russian Orthodox Church formed a significant part of Kiev's infrastructure and business activity. In the late 1840s, the historian, Mykola Kostomarov (Russian: Nikolay Kostomarov), founded a secret political society, the Brotherhood of Saint Cyril and Methodius, whose members put forward the idea of a federation of free Slavic people with Ukrainians as a distinct and separate group rather than a subordinate part of the Russian nation; the society was quickly suppressed by the authorities.

Following the gradual loss of Ukraine's autonomy, Kiev experienced growing Russification in the 19th century by means of Russian migration, administrative actions and social modernization. At the beginning of the 20th century, the city centre was dominated by the Russian-speaking part of the population, while the lower classes living on the outskirts retained Ukrainian folk culture to a significant extent. However, enthusiasts among ethnic Ukrainian nobles, military and merchants made recurrent attempts to preserve native culture in Kiev (by clandestine book-printing, amateur theatre, folk studies etc.)

During the Russian industrial revolution in the late 19th century, Kiev became an important trade and transportation centre of the Russian Empire, specialising in sugar and grain export by railway and on the Dnieper river. By 1900, the city had also become a significant industrial centre, having a population of 250,000. Landmarks of that period include the railway infrastructure, the foundation of numerous educational and cultural facilities as well as notable architectural monuments (mostly merchant-oriented). The first electric tram line of the Russian Empire was established in Kiev (arguably, the first in the world).

Kiev prospered during the late 19th century Industrial Revolution in the Russian Empire, when it became the third most important city of the Empire and the major centre of commerce of its southwest. In the turbulent period following the 1917 Russian Revolution, Kiev became the capital of several short-lived Ukrainian states and was caught in the middle of several conflicts: World War I, during which it was occupied by German soldiers from 2 March 1918 to November 1918, the Russian Civil War, and the Polish–Soviet War. Kiev changed hands sixteen times from the end of 1918 to August 1920.[44]

Starting in 1921, the city was a part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, a founding republic of the Soviet Union. Kiev was greatly affected by all the major processes that took place in Soviet Ukraine during the interwar period: the 1920s Ukrainization as well as the migration of the rural Ukrainophone population made the Russophone city Ukrainian-speaking and propped up the development of the Ukrainian cultural life in the city; the Soviet Industrialization that started in the late 1920s turned the city, a former centre of commerce and religion, into a major industrial, technological and scientific centre, the 1932–1933 Great Famine devastated the part of the migrant population not registered for the ration cards, and Joseph Stalin's Great Purge of 1937–1938 almost eliminated the city's intelligentsia[45][46][47]

In 1934 Kiev became the capital of Soviet Ukraine. The city boomed again during the years of the Soviet industrialization as its population grew rapidly and many industrial giants were created, some of which exist to this day.

In World War II, the city again suffered significant damage, and was occupied by Nazi Germany from 19 September 1941 to 6 November 1943. More than 600,000 Soviet soldiers were killed or captured in the great encirclement Battle of Kiev in 1941. Most of them never returned alive.[48] Shortly after the city was occupied, a team of NKVD officers that had remained hidden dynamited most of the buildings on the Khreshchatyk, the main street of the city, most of whose buildings were being used by German military and civil authorities; the buildings burned for days and 25,000 people were left homeless.

Allegedly in response to the actions of the NKVD, the Germans rounded up all the local Jews they could find, nearly 34,000,[49] and massacred them at Babi Yar over the course of 29–30 September 1941.[50][51] In the months that followed, thousands more were taken to Babi Yar where they were shot. It is estimated that more than 100,000 people of various ethnic groups, mostly civilians, were murdered by the Germans there during World War II.[52]

Kiev recovered economically in the post-war years, becoming once again the third most important city of the Soviet Union. The catastrophic accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in 1986 occurred only 100 km (62 mi) north of the city. However, the prevailing northward winds blew most of the radioactive debris away from the city.

In the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine was proclaimed in the city by the Ukrainian parliament on 24 August 1991. In 2004–2005, the city played host to until then the largest post-Soviet public demonstrations, in support of the Orange Revolution. From November 2013 until February 2014, central Kiev was the primary location of Euromaidan.

Environment

Geography

Geographically, Kiev belongs to the Polesia ecological zone (a part of the European mixed woods). However, the city's unique landscape distinguishes it from the surrounding region. Kiev is completely surrounded by Kiev Oblast.

Kiev is located on both sides of the Dnieper River, which flows south through the city towards the Black Sea. The older right-bank (western) part of the city is represented by numerous woody hills, ravines and small rivers. It is a part of the larger Dnieper Upland adjoining the western bank of the Dnieper in its mid-flow. Kiev expanded to the Dnieper's lowland left bank (to the east) only in the 20th century. Significant areas of the left-bank Dnieper valley were artificially sand-deposited, and are protected by dams.

The Dnieper River forms a branching system of tributaries, isles, and harbors within the city limits. The city is adjoined by the mouth of the Desna River and the Kiev Reservoir in the north, and the Kaniv Reservoir in the south. Both the Dnieper and Desna rivers are navigable at Kiev, although regulated by the reservoir shipping locks and limited by winter freeze-over.

In total, there are 448 bodies of open water within the boundaries of Kiev, which include Dnieper itself, its reservoirs, and several small rivers, dozens of lakes and artificially created ponds. They occupy 7949 hectares of territory. Additionally, the city boasts of 16 developed beaches (totalling 140 hectares) and 35 near-water recreational areas (covering more than 1000 hectares). Many are used for pleasure and recreation, although some of the bodies of water are not suitable for swimming.[53]

According to the UN 2011 evaluation, there were no risks of natural disasters in Kiev and its metropolitan area[54]

Climate

Kiev has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb).[55] The warmest months are June, July, and August, with mean temperatures of 13.8 to 24.8 °C (56.8 to 76.6 °F). The coldest are December, January, and February, with mean temperatures of −4.6 to −1.1 °C (23.7 to 30.0 °F). The highest ever temperature recorded in the city was 39.4 °C (102.9 °F) on 30 July 1936.[56][57] The coldest temperature ever recorded in the city was −32.9 °C (−27.2 °F) on 11 January 1951.[56][57] Snow cover usually lies from mid-November to the end of March, with the frost-free period lasting 180 days on average, but surpassing 200 days in recent years.[58]

| Climate data for Kiev (1981–2010, extremes 1881–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.1 (52) |

17.3 (63.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

33.6 (92.5) |

35.0 (95) |

39.4 (102.9) |

39.3 (102.7) |

33.8 (92.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

23.2 (73.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.9 (30.4) |

0.0 (32) |

5.6 (42.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

0.0 (32) |

12.5 (54.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.5 (25.7) |

−3 (27) |

1.8 (35.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −5.8 (21.6) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

5.1 (41.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.2 (57.6) |

16.1 (61) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

4.9 (40.8) |

0.0 (32) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.9 (−27.2) |

−32.2 (−26) |

−24.9 (−12.8) |

−10.4 (13.3) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

2.4 (36.3) |

5.8 (42.4) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−17.8 (0) |

−21.9 (−7.4) |

−30.0 (−22) |

−32.9 (−27.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36 (1.42) |

39 (1.54) |

37 (1.46) |

46 (1.81) |

57 (2.24) |

82 (3.23) |

71 (2.8) |

60 (2.36) |

57 (2.24) |

41 (1.61) |

50 (1.97) |

45 (1.77) |

621 (24.45) |

| Average rainy days | 8 | 7 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 138 |

| Average snowy days | 17 | 17 | 10 | 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 2 | 9 | 16 | 73 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 80 | 74 | 64 | 62 | 67 | 68 | 67 | 74 | 77 | 85 | 86 | 74 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 42 | 64 | 112 | 162 | 257 | 273 | 287 | 252 | 189 | 123 | 51 | 31 | 1,843 |

| Source #1: Pogoda.ru.net,[59] Central Observatory for Geophysics (extremes)[56][57] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Danish Meteorological Institute (sun, 1931–1960)[60] | |||||||||||||

Legal status, local government and politics

Legal status and local government

The municipality of the city of Kiev has a special legal status within Ukraine compared to the other administrative subdivisions of the country. The most significant difference is that the city is considered as a region of Ukraine (see Regions of Ukraine). It is the only city that has double jurisdiction. The Head of City State Administration — the city's governor, is appointed by the President of Ukraine, while the Head of the City Council — the Mayor of Kiev, is elected by a local popular vote.

The current Mayor of Kiev is Vitali Klitschko who was sworn in on 5 June 2014;[2] after he had won the 25 May 2014 Kiev mayoral elections with almost 57% of the votes.[61] Since 25 June 2014 Klitschko is also Head of Kiev City Administration.[3]

Most important buildings of the national government (Cabinet of Ukraine, Verkhovna Rada, others) are located along vulytsia Mykhaila Hrushevskoho (Mykhailo Hrushevsky Street) and vulytsia Instytutska (Institute Street). Hrushevskoho Street is named after the Ukrainian academician, politician, historian, and statesman Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, who wrote an academic book titled: "Bar Starostvo: Historical Notes: XV-XVIII" about the history of Bar, Ukraine.[62] That portion of the city is also unofficially known as the government quarter (Ukrainian: урядовий квартал). The city also has a great number of buildings for various embassies, ministerial and other important buildings.

The city state administration and council is located in the Kiev City's council building on Khreshchatyk Street. The oblast state administration and council is located in the Kiev Oblast council building on ploshcha Lesi Ukrayinky (Lesya Ukrayinka Square). The Kiev-Sviatoshyn Raion state administration is located near Kiltseva doroha (Ring Road) on prospekt Peremohy (Victory Parkway), while the Kiev-Svyatoshyn Raion local council is located on vulytsia Yantarna (Yantarnaya Street).

| Government buildings in Kiev | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Politics

The growing political and economic role of the city, combined with its international relations, as well as extensive internet and social network penetration,[63] have made Kiev the most pro-Western and pro-democracy region of Ukraine; (so called) National Democratic parties advocating tighter integration with the European Union receive most votes during elections in Kiev.[12][13][14][15] In a poll conducted by the Kiev International Institute of Sociology in the first half of February 2014, 5.3% of those polled in Kiev believed "Ukraine and Russia must unite into a single state", nationwide this percentage was 12.5.[64]

Subdivisions

Traditional subdivision

The Dnieper River naturally divides Kiev into the Right Bank and the Left Bank areas. Historically located on the western right bank of the river, the city expanded into the left bank only in the 20th century. Most of Kiev's attractions as well as the majority of business and governmental institutions are located on the right bank. The eastern 'Left Bank' is predominantly residential. There are large industrial and green areas in both the Right Bank and the Left Bank.

Kiev is further informally divided into historical or territorial neighbourhoods, each housing from about 5,000 to 100,000 inhabitants.

Formal subdivision

|

Right-bank districts

Left-bank districts

|

|

The first known formal subdivision of Kiev dates to 1810 when the city was subdivided into 4 parts: Pechersk, Starokyiv, and the first and the second parts of Podil. In 1833–1834 according to Tsar Nicholas I's decree, Kiev was subdivided into 6 police raions (districts); later being increased to 10. In 1917, there were 8 Raion Councils (Duma), which were reorganised by bolsheviks into 6 Party-Territory Raions.

During the Soviet era, as the city was expanding, the number of raions also gradually increased. These newer districts of the city, along with some older areas were then named in honour of prominent communists and socialist-revolutionary figures; however, due to the way in which many communist party members eventually, after a certain period of time, fell out of favour and so were replaced with new, fresher minds, so too did the names of Kiev's districts change accordingly.

The last raion reform took place in 2001 when the number of raions has been decreased from 14 to 10.

Under Oleksandr Omelchenko (mayor from 1999 to 2006), there were further plans for the merger of some raions and revision of their boundaries, and the total number of raions had been planned to be decreased from 10 to 7. With the election of the new mayor-elect (Leonid Chernovetsky) in 2006, these plans were shelved.

Each raion has its own locally elected government with jurisdiction over a limited scope of affairs.

Demographics

According to the official registration statistics, there were 2,847,200 residents within the city limits of Kiev in July 2013.[4]

Historical population

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 10xx | 100,000 | — |

| 1647 | 15,000 | −85.0% |

| 1666 | 10,000 | −33.3% |

| 1763 | 42,000 | +320.0% |

| 1797 | 19,000 | −54.8% |

| 1835 | 36,500 | +92.1% |

| 1845 | 50,000 | +37.0% |

| 1856 | 56,000 | +12.0% |

| 1865 | 71,300 | +27.3% |

| 1874 | 127,500 | +78.8% |

| 1884 | 154,500 | +21.2% |

| 1897 | 247,700 | +60.3% |

| 1905 | 450,000 | +81.7% |

| 1909 | 468,000 | +4.0% |

| 1912 | 442,000 | −5.6% |

| 1914 | 626,300 | +41.7% |

| 1917 | 430,500 | −31.3% |

| 1919 | 544,000 | +26.4% |

| 1922 | 366,000 | −32.7% |

| 1923 | 413,000 | +12.8% |

| 1926 | 513,000 | +24.2% |

| 1930 | 578,000 | +12.7% |

| 1940 | 930,000 | +60.9% |

| 1943 | 180,000 | −80.6% |

| 1956 | 991,000 | +450.6% |

| 1959 | 1,104,300 | +11.4% |

| 1965 | 1,367,200 | +23.8% |

| 1970 | 1,632,000 | +19.4% |

| 1975 | 1,947,000 | +19.3% |

| 1980 | 2,191,500 | +12.6% |

| 1985 | 2,461,000 | +12.3% |

| 1991 | 2,593,400 | +5.4% |

| 1996 | 2,637,900 | +1.7% |

| 2000 | 2,615,300 | −0.9% |

| 2005 | 2,596,400 | −0.7% |

| 2010 | 2,786,518 | +7.3% |

| 2015 | 2,890,432 | +3.7% |

| at 1 January of respective year.[65][66] | ||

According to the All-Ukrainian Census, the population of Kiev in 2001 was 2,611,300.[8] The historic changes in population are shown in the side table. According to the census men accounted for 1,219,000 persons, or 46.7%, and women for 1,393,000 persons, or 53.3%. Comparing the results with the previous census (1989) shows the trend of population ageing which, while prevalent throughout the country, is partly offset in Kiev by the inflow of working age migrants. Some 1,069,700 people had higher or completed secondary education, a significant increase of 21.7% since 1989.

The June 2007 unofficial population estimate based on amount of bakery products sold in the city (thus including temporary visitors and commuters) gave a number of at least 3.5 million people.[67]

Ethnic composition

According to the 2001 census data, more than 130 nationalities and ethnic groups reside within the territory of Kiev. Ukrainians constitute the largest ethnic group in Kiev, and they account for 2,110,800 people, or 82.2% of the population. Russians comprise 337,300 (13.1%), Jews 17,900 (0.7%), Belarusians 16,500 (0.6%), Poles 6,900 (0.3%), Armenians 4,900 (0.2%), Azerbaijanis 2,600 (0.1%), Tatars 2,500 (0.1%), Georgians 2,400 (0.1%), Moldovans 1,900 (0.1%).

Both Ukrainian and Russian are commonly spoken in the city; approximately 75% of Kiev's population responded "Ukrainian" to the 2001 census question on their native language, roughly 25% responded "Russian".[68] According to a 2006 survey, Ukrainian is used at home by 23% of Kievans, 52% use Russian and 24% switch between both.[69] In the 2003 sociological survey, when the question 'What language do you use in everyday life?' was asked, 52% said 'mostly Russian', 32% 'both Russian and Ukrainian in equal measure', 14% 'mostly Ukrainian', and 4.3% 'exclusively Ukrainian'.[70]

According to the census of 1897, of Kiev's approximately 240,000 people approximately 56% of the population spoke the Russian language, 23% spoke the Ukrainian language, 13% spoke Yiddish, 7% spoke Polish and 1% spoke the Belarusian language.[71]

Most of the city's population of Muslims comprises Tatars, Caucasians and other people from the former Soviet Union. The Ar-Rahma Mosque was built in 2000.

A 2015 study by the International Republican Institute found that 94% of Kiev was ethnic Ukrainian, and 5% ethnic Russian. The languages spoken at home were Ukrainian (27%), Russian (32%), and an equal combination of Ukrainian and Russian (40%).[72]

Jewish community

The Jews in Kiev are first mentioned in a 10th century letter. They experienced several pogroms, including the Babi Yar massacre during the Holocaust. Today there are approximately 20,000 Jews in Kiev, with two major synagogues: the Great Choral Synagogue and the Brodsky Choral Synagogue.[73]

Cityscape

Modern Kiev is a mix of the old (Kiev preserved about 70 percent of more than 1,000 buildings built during 1907–1914[74]) and the new, seen in everything from the architecture to the stores and to the people themselves. When the capital of the Ukrainian SSR was moved from Kharkiv to Kiev many new buildings were commissioned to give the city "the gloss and polish of a capital".[74] In the discussions centered on how to create a showcase city center the current city center of Khreshchatyk and Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) were not the obvious choices.[74] Some of the early, ultimately not materialised, ideas included a part of Pechersk, Lypky, European Square and Mykhailivska Square.[74] The plans of building massive monuments (of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin) were also abandoned; due to lack of money (in the 1930s–1950s) and because of Kiev's hilly landscape.[74] Experiencing rapid population growth between the 1970s and the mid-1990s, the city has continued its consistent growth after the turn of the millennium. As a result, Kiev's central districts provide a dotted contrast of new, modern buildings among the pale yellows, blues and greys of older apartments. Urban sprawl has gradually reduced, while population densities of suburbs has increased. The most expensive properties are located in the Pechersk, and Khreshchatyk areas. It is also prestigious to own a property in newly constructed buildings in the Kharkivskyi Raion or Obolon along the Dnieper.

Ukrainian independence at the turn of the millennium has heralded other changes. Western-style residential complexes, modern nightclubs, classy restaurants and prestigious hotels opened in the centre. And most importantly, with the easing of the visa rules in 2005,[75] Ukraine is positioning itself as a prime tourist attraction, with Kiev, among the other large cities, looking to profit from new opportunities. The centre of Kiev has been cleaned up and buildings have been restored and redecorated, especially Khreshchatyk and Maidan Nezalezhnosti. Many historic areas of Kiev, such as Andriyivskyy Descent, have become popular street vendor locations, where one can find traditional Ukrainian art, religious items, books, game sets (most commonly chess) as well as jewellery for sale.[76]

At the United Nations Climate Change Conference 2009 Kiev was the only Commonwealth of Independent States city to have been inscribed into the TOP30 European Green City Index (placed 30th).[77]

Kiev's most famous historical architecture complexes are the St. Sophia Cathedral and the Kiev Pechersk Lavra (Monastery of the Caves), which are recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. Noteworthy historical architectural landmarks also include the Mariyinsky Palace (designed and constructed from 1745 to 1752, then reconstructed in 1870), several Orthodox churches such as St. Michael's Cathedral, St. Andrew's, St. Vladimir's, the reconstructed Golden Gate and others.

One of Kiev's widely recognized modern landmarks is the highly visible giant Mother Motherland statue made of titanium standing at the Museum of The History of Ukraine in World War II on the Right bank of the Dnieper River. Other notable sites is the cylindrical Salut hotel, located across from Glory Square and the eternal flame at the World War Two memorial Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, and the House with Chimaeras.

Among Kiev's best-known monuments are Mikhail Mikeshin's statue of Bohdan Khmelnytsky astride his horse located near St. Sophia Cathedral, the venerated Vladimir the Great (St. Vladimir), the baptizer of Rus', overlooking the river above Podil from Volodymyrska Hill, the monument to Kyi, Schek and Khoryv and Lybid, the legendary founders of the city located at the Dnieper embankment. On Independence Square in the city centre, two monuments elevate two of the city protectors; the historic protector of Kiev Michael Archangel atop a reconstruction of one of the old city's gates and a modern invention, the goddess-protector Berehynia atop a tall column.

| Architecturally important and historically significant sites and monuments in Kiev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Culture

Kiev was the historic cultural centre of the East Slavic civilization and a major cradle for the Christianization of Kievan Rus'. Kiev retained through centuries its cultural importance and even at times of relative decay, it remained the centre of primary importance of Eastern Orthodox Christianity . Its sacred sites, which include the Kiev Pechersk Lavra (the Monastery of the Caves) and the Saint Sophia Cathedral are probably the most famous, attracted pilgrims for centuries and now recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site remain the primary religious centres as well as the major tourist attraction. The above-mentioned sites are also part of the Seven Wonders of Ukraine collection.

Kiev's theatres include, the Kiev Opera House, Ivan Franko National Academic Drama Theater, Lesya Ukrainka National Academic Theater of Russian Drama, the Kiev Puppet Theater, October Palace and National Philharmonic of Ukraine and others. In 1946 Kiev had four theatres, one opera house and one concert hall,[78] but most tickets then were allocated to "privileged groups".[78]

Other significant cultural centres include the Dovzhenko Film Studios, and the Kiev Circus. The most important of the city's many museums are the Kiev State Historical Museum, Museum of The History of Ukraine in World War II, the National Art Museum, the Museum of Western and Oriental Art, the Pinchuk Art Centre and the National Museum of Russian art.

In 2005 Kiev hosted the 50th annual Eurovision Song Contest as a result of Ruslana's "Wild Dances" victory in 2004.

Numerous songs and paintings were dedicated to the city. Some songs became part of Russian, Ukrainian, and Polish folklore, less known are German and Jewish. The most popular songs are "Without Podil, Kiev is impossible" and "How not to love you, Kiev of mine?". Renowned Ukrainian composer Oleksandr Bilash wrote an operetta called "Legend of Kiev".

Attractions

It is said that one can walk from one end of Kiev to the other in the summertime without leaving the shade of its many trees. Most characteristic are the horse-chestnuts (Ukrainian: каштани, kashtany).

Kiev is known as a green city with two botanical gardens and numerous large and small parks. The Museum of The History of Ukraine in World War II is located here, which offers both indoor and outdoor displays of military history and equipment surrounded by verdant hills overlooking the Dnieper river.

Among the numerous islands, Venetsianskyi (or Hydropark) is the most developed. It is accessible by metro or by car, and includes an amusement park, swimming beaches, boat rentals, and night clubs. The Victory Park (Park Peremohy) located near Darnytsia subway station is a popular destination for strollers, joggers, and cyclists. Boating, fishing, and water sports are popular pastimes in Kiev. The area lakes and rivers freeze over in the winter and ice fishermen are a frequent sight, as are children with their ice skates. However, the peak of summer draws out a greater mass of people to the shores for swimming or sunbathing, with daytime high temperatures sometimes reaching 30 to 34 °C (86 to 93 °F).

The centre of Kiev (Independence Square and Khreschatyk Street) becomes a large outdoor party place at night during summer months, with thousands of people having a good time in nearby restaurants, clubs and outdoor cafes. The central streets are closed for auto traffic on weekends and holidays. Andriyivskyy Descent is one of the best known historic streets and a major tourist attraction in Kiev. The hill is the site of the Castle of Richard the Lionheart; the baroque-style St Andrew's Church; the home of Kiev born writer, Mikhail Bulgakov; the monument to Yaroslav the Wise, the Grand Prince of Kiev and of Novgorod; and numerous other monuments.[79][80]

A wide variety of farm produce is available in many of Kiev's farmer markets with the Besarabsky Market located in the very centre of the city being most famous. Each residential region has its own market, or rynok. Here one will find table after table of individuals hawking everything imaginable: vegetables, fresh and smoked meats, fish, cheese, honey, dairy products such as milk and home-made smetana (sour cream), caviar, cut flowers, housewares, tools and hardware, and clothing. Each of the markets has its own unique mix of products with some markets devoted solely to specific wares such as automobiles, car parts, pets, clothing, flowers, and other things.

At the city's southern outskirts, near the historic Pyrohiv village, there is an outdoor museum, officially called the Museum of Folk Architecture and Life of Ukraine It has an area of 1.5 square kilometres (1 sq mi). This territory houses several "mini-villages" that represent by region the traditional rural architecture of Ukraine.

Kiev also has numerous recreational attractions like bowling alleys, go-cart tracks, paintball venues, billiard halls and even shooting ranges. The 100-year-old Kiev Zoo is located on 40 hectares and according to CBC "the zoo has 2,600 animals from 328 species".[81]

Museums and galleries

Kiev is home to some 40 different museums.[82] In 2009 they recorded a total of 4.3 million visits.[82]

The Museum of The History of Ukraine in World War II is a memorial complex commemorating the Eastern Front of World War II located in the hills on the right-bank of the Dnieper River in Pechersk. Kiev fortress is the 19th-century fortification buildings situated in Ukrainian capital Kiev, that once belonged to western Russian fortresses. These structures (once a united complex) were built in the Pechersk and neighbourhoods by the Russian army. Now some of the buildings are restored and turned into a museum called the Kiev Fortress, while others are in use in various military and commercial installations. The National Art Museum of Ukraine is a museum dedicated to Ukrainian art. The Golden Gate is a historic gateway in the ancient city's walls. The name Zoloti Vorota is also used for a nearby theatre and a station of the Kiev Metro. The small Ukrainian National Chernobyl Museum acts as both a memorial and historical center devoted to the events surrounding the 1986 Chernobyl disaster and its effect on the Ukrainian people, the environment, and subsequent attitudes toward the safety of nuclear power as a whole.

Sports

._%D0%A1%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%82..jpg)

Kiev has many professional and amateur football clubs, including Dynamo Kyiv, Arsenal Kyiv and FC Obolon Kyiv which play in the Ukrainian Premier League. Of these three, Dynamo Kyiv has had the most success over the course of its history. For example, up until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the club won 13 USSR Championships, 9 USSR Cups, and 3 USSR Super Cups, thus making Dynamo the most successful club in the history of the Soviet Top League.[83]

Other prominent non-football sport clubs in the city include: the Sokil Kiev ice hockey club and BC Kyiv basketball club. Both of these teams play in the highest Ukrainian leagues for their respective sports and whilst BC Kyiv was founded just recently in 1999, Sokil was founded in 1963, during the existence of the Soviet Union. Both these teams play their home games at the Kiev Palace of Sports.

During the 1980 Summer Olympics held in the Soviet Union, Kiev held the preliminary matches and the quarter-finals of the football tournament at its Olympic Stadium, which was reconstructed specially for the event. From 1 December 2008 stadium the stadium underwent a full-scale reconstruction in order to satisfy standards put in place by UEFA for hosting the Euro 2012 football tournament; the opening ceremony took place in the presence of president Viktor Yanukovich on 8 October 2011,[84] with the first major event being a Shakira concert which was specially planned to coincide with the stadium's re-opening during Euro 2012. Other notable sport stadiums/sport complexes in Kiev include the Lobanovsky Dynamo Stadium, the Palace of Sports, among many others.

Most Ukrainian national teams play their home international matches in Kiev. The Ukraine national football team, for example, will play matches at the re-constructed Olympic Stadium from 2011.

Tourism

Since introducing a visa-free regime for EU-member states and Switzerland in 2005, Ukraine has seen a steady increase in the number of foreign tourists visiting the country.[85] Prior to the 2008–2009 recession the average annual growth in the number of foreign visits in Kiev was 23% over a three-year period.[86] In 2009 a total of 1.6 million tourists stayed in Kiev hotels of which almost 259,000 (ca. 16%) were foreigners.[86]

Economy

See also: Category:Economy of Kiev, Economy of Ukraine

As with most capital cities, Kiev is a major administrative, cultural and scientific centre of the country. It is the largest city in Ukraine in terms of both population and area and enjoys the highest levels of business activity. On 1 January 2010 there were around 238,000 business entities registered in Kiev.[87]

Official figures show that between 2004 and 2008 Kiev's economy outstripped the rest of the country's, growing by an annual average of 11.5%.[88][89] Following the global financial crisis that began in 2007, Kiev's economy suffered a severe setback in 2009 with gross regional product contracting by 13.5% in real terms.[88] Although a record high, the decline in activity was 1.6 percentage points smaller than that for the country as a whole.[89] The economy in Kiev, as in the rest of Ukraine, recovered somewhat in 2010 and 2011. Kiev is a middle-income city, with prices currently comparable to many mid-size American cities (i.e., considerably lower than Western Europe).

Because the city boasts a large and diverse economic base and is not dependent on any single industry and/or company, its unemployment rate has historically been relatively low – only 3.75% over 2005–2008.[90] Indeed, even as the rate of joblessness jumped to 7.1% in 2009, it remained far below the national average of 9.6%.[90][91]

Kiev is the undisputed center of business and commerce of Ukraine and home to the country's largest companies, such as Naftogaz Ukrainy, Energorynok and Kyivstar. In 2010 the city accounted for 18% of national retail sales and 24% of all construction activity.[92][93][94][95] Indeed, real estate is one of the major forces in Kiev's economy. Average prices of apartments are the highest in the country and among the highest in eastern Europe.[96] Kiev also ranks high in terms of commercial real estate for it is here where the country's tallest office buildings (such as Gulliver and Parus) and some of Ukraine's biggest shopping malls (such as Dream Town and Ocean Plaza) are located.

In May 2011 Kiev authorities presented a 15-year development strategy which calls for attracting as much as EUR82 billion of foreign investment by 2025 to modernize the city’s transport and utilities infrastructure and make it more attractive for tourists.[97]

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal GRP (UAH bn)[88] | 61.4 | 77.1 | 95.3 | 135.9 | 169.6 | 169.5 | 196.6 | 223.8 | 275.7 | |

| Nominal GRP (USD bn)**[88][98] | 11.5 | 15.0 | 18.9 | 26.9 | 32.2 | 21.8 | 24.8 | 28.0 | 34.5 | |

| Nominal GRP per capita (USD)**[88][98] | 4,348 | 5,616 | 6,972 | 9,860 | 11,693 | 7,841 | 8,875 | 10,007 | 12,192 | |

| Monthly wage (USD)**[98][99] | 182 | 259 | 342 | 455 | 584 | 406 | 432 | 504 | 577 | |

| Unemployment rate (%)***[100] | n/a | 4.6 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.7 |

| Retail sales (UAH bn)[92] | n/a | n/a | n/a | 34.87 | 46.50 | 42.79 | 50.09 | 62.80 | 73.00 | 77.14 |

| Retail sales (USD bn)[92][98] | n/a | n/a | n/a | 6.90 | 8.83 | 5.49 | 6.31 | 7.88 | 9.14 | 9.65 |

| Foreign direct investment (USD bn)[101] | 2.1 | 3.0 | 4.8 | 7.0 | 11.7 | 16.8 | 19.2 | 21.8 | 24.9 | 27.3 |

* – data not available; ** – calculated at annual average official exchange rate; *** – ILO methodology (% of workforce).

Industry

Primary industries in Kiev include utilities – i.e., electricity, gas and water supply (26% of total industrial output), manufacture of food, beverages and tobacco products (22%), chemical (17%), mechanical engineering (13%) and manufacture of paper and paper products, including publishing, printing and reproduction of recorded media (11%).[102] The Institute of Oil Transportation is headquartered here.

Manufacture

- Leninska Kuznya, naval production

- Antonov Serial Production Plant (former Aviant), airplanes manufacturing

- Aeros, small aircraft production

- Kiev Roshen Factory, confectionery

- Kiev Arsenal (former arms manufacturer), specializes in production of optic-precision instruments

- Obolon, brewery

- Kiev Aircraft Repair Plant 410, repair factory located at Zhulyany Airport

Education and science

Scientific research

Scientific research is conducted in many institutes of higher education and, additionally, in many research institutes affiliated with the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. Kiev is home to Ukraine's ministry of education and science, and is also noted for its contributions to medical and computer science research.

University education

Kiev hosts many universities, the major ones being Kiev National Taras Shevchenko University,[103] the National Technical University "Kiev Polytechnic Institute",[104] and the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.[105] Of these, the Mohyla Academy is the oldest outright, having been founded as a theological school in 1632, however the Shevchenko University, which was founded in 1834, is the oldest in continuous operation. The total number of institutions of higher education in Kiev currently approaches 200,[106] allowing young people to pursue almost any line of study. While education traditionally remains largely in the hands of the state there are several accredited private institutions in the city.

Secondary education

There are about 530 general secondary schools and ca. 680 nursery schools and kindergartens in Kiev.[107] Additionally, there are evening schools for adults, and specialist technical schools.

Public libraries

There are many libraries in the city with the Vernadsky National Library, which is Ukraine's main academic library and scientific information centre, as well as one of the world's largest national libraries, being the largest and most important one.[108] The National Library is affiliated with the Academy of Sciences in so far as it is a deposit library and thus serves as the academy's archives' store. Interestingly the national library is the world’s foremost repository of Jewish folk music recorded on Edison wax cylinders. Their Collection of Jewish Musical Folklore (1912–1947) was inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in 2005.[109]

Transportation

Local public transport

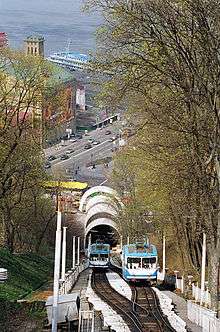

Local public transportation in Kiev includes the Metro (underground), buses and minibuses, trolleybuses, trams, taxi and funicular. There is also an intra-city ring railway service.

The publicly owned and operated Kiev Metro is the fastest, the most convenient and affordable network that covers most, but not all, of the city. The Metro is continuously expanding towards the city limits to meet growing demand, currently having three lines with a total length of 66.1 kilometres (41.1 miles) and 51 stations (some of which are renowned architectural landmarks). The Metro carries around 1.422 million passengers daily[110] accounting for 38% of the Kiev's public transport load. In 2011, the total number of trips exceeded 519 million.

The historic Kiev tram system was the first electric tramway in the former Russian Empire and the third one in Europe after the Berlin Straßenbahn and the Budapest tramway. The tram system currently consists of 139.9 km (86.9 mi) of track,[111] including 14 km (8.7 mi) two Rapid Tram lines, served by 21 routes with the use of 523 tram cars. Once a well maintained and widely used method of transport, the system is now gradually being phased out in favor of buses and trolleybuses.

The Kiev funicular was constructed during 1902–1905. It connects the historic Uppertown, and the lower commercial neighborhood of Podil through the steep Volodymyrska Hill overseeing the Dnieper River. The line consists of only two stations.

All public road transport (except for some minibuses) is operated by the united Kyivpastrans municipal company. It is heavily subsidized by the city.

The Kiev public transport system, except for taxi, uses a simple flat rate tariff system regardless of distance traveled: tickets or tokens must be purchased each time a vehicle is boarded. Digital ticket system is already established in Kiev Metro, with plans for other transport modes. Discount passes are available for grade school and higher education students. Pensioners use public transportation free. There are monthly passes in all combinations of public transportation. Ticket prices are regulated by the city government, and the cost of one ride is far lower than in Western Europe.

The taxi market in Kiev is expansive but not regulated. In particular, the taxi fare per kilometer is not regulated. There is a fierce competition between private taxi companies.

Roads and bridges

Kiev represents the focal point of Ukraine's "national roads" system, thus linked by road to all cities of the country. European routes ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() cross Kiev.

cross Kiev.

There are 8 over-Dnieper bridges and dozens of grade-separated intersections in the city. Several new intersections are under construction. There are plans to build a full-size, fully grade-separated ring road around Kiev.[112][113][114]

Overall, Kiev roads are in poor technical condition and maintained inadequately.[115]

Traffic jams and lack of parking space are growing problems for all road transport services in Kiev.

Air transport

Kiev is served by two international passenger airports: the Boryspil Airport located 30 kilometres (19 miles) away, and the smaller, municipally owned Zhulyany Airport on the southern outskirts of the city. There are also the Gostomel cargo airport and additional three operating airfields facilitating the Antonov aircraft manufacturing company and general aviation.

Railways

Railways are Kiev’s main mode of intracity and suburban transportation. The city has a developed railroad infrastructure including a long-distance passenger station, 6 cargo stations, depots, and repairing facilities. However, this system still fails to meet the demand for passenger service. Particularly, the Kiev Passenger Railway Station is the city's only long-distance passenger terminal (vokzal).

Construction is underway for turning the large Darnytsia Railway Station on the left-bank part of Kiev into a long-distance passenger hub, which may ease traffic at the central station.[116] Bridges over the Dnieper River are another problem restricting the development of city’s railway system. Presently, only one rail bridge out of two is available for intense train traffic. A new combined rail-auto bridge is under construction, as a part of Darnytsia project.

In 2011 the Kiev city administration established a new 'Urban Train' for Kiev. This service runs at standard 4- to 10-minute intervals throughout the day and follows a circular route around the city centre, which allows it to serve many of Kiev's inner suburbs. Interchanges between the Kiev Metro and Fast Tram exist at many of the urban train's station stops.[117]

Suburban 'Elektrichka' trains are serviced by the publicly owned Ukrainian Railways. The suburban train service is fast, and unbeatably safe in terms of traffic accidents. But the trains are not reliable, as they may fall significantly behind schedule, may not be safe in terms of crime, and the elektrichka cars are poorly maintained and are overcrowded in rush hours.

There are 5 elektrichka directions from Kiev:

- Nizhyn (north-eastern)

- Hrebinka (south-eastern)

- Myronivka (southern)

- Fastiv (south-western)

- Korosten (western)

More than a dozen of elektrichka stops are located within the city allowing residents of different neighborhoods to use the suburban trains.

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

Kiev is twinned with:

Ankara, Turkey (since 1993)[118]

Ankara, Turkey (since 1993)[118] Baku, Azerbaijan[119]

Baku, Azerbaijan[119] Beijing, China (since 1993)[120]

Beijing, China (since 1993)[120] Bratislava, Slovakia[121]

Bratislava, Slovakia[121] Chicago, Illinois, United States[122]

Chicago, Illinois, United States[122] Chişinău, Moldova (since 1999)[123]

Chişinău, Moldova (since 1999)[123] Edinburgh, Scotland, UK (since 1989)[124]

Edinburgh, Scotland, UK (since 1989)[124] Florence, Italy[125]

Florence, Italy[125] Kastoria, Greece (since 1998)[126]

Kastoria, Greece (since 1998)[126] Kraków, Poland (since 1993)[127]

Kraków, Poland (since 1993)[127] Kyoto, Japan[128]

Kyoto, Japan[128] Leipzig, Germany (since 1961)[129]

Leipzig, Germany (since 1961)[129] Munich, Germany[130]

Munich, Germany[130] Odense, Denmark[131]

Odense, Denmark[131] Riga, Latvia (since 1998)[132]

Riga, Latvia (since 1998)[132] Rio de Janeiro, Brazil[133]

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil[133] Tbilisi, Georgia (since 1999)[134]

Tbilisi, Georgia (since 1999)[134] Vienna, Austria[135]

Vienna, Austria[135] Vilnius, Lithuania[136]

Vilnius, Lithuania[136] Warsaw, Poland (since 1994)[137]

Warsaw, Poland (since 1994)[137]

In February 2016 the Kiev city council terminated its twinned relations with the Russian cities Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Volgograd, Ulan-Ude, Makhachkala, and the Komi Republic due to the Russian military intervention in Ukraine.[138][139]

Other cooperation agreements

Honour

- Kiev Peninsula in Graham Land, Antarctica is named after the city of Kiev.[144]

References

- ↑ "Kyiv's 1,530th birthday marked with fun, protest".

- 1 2 Vitali Klitschko sworn in as Kyiv mayor, Interfax-Ukraine (5 June 2014)

- 1 2 Poroshenko appoints Klitschko head of Kyiv city administration – decree, Interfax-Ukraine (25 June 2014)

Poroshenko orders Klitschko to bring title of best European capital back to Kyiv, Interfax-Ukraine (25 June 2014) - 1 2 3 "Чисельність населення м.Києва" (in Ukrainian). UkrStat.gov.ua. 1 November 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ "Major Agglomerations of the World". Citypopulation.de. 1 April 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ kievan. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged, retrieved 29 May 2013 from Dictionary.com

- ↑ "Kiev". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- 1 2 The most recent Ukrainian census, conducted on 5 December 2001, gave the population of Kiev as 2 611 300 (Ukrcensus.gov.ua – Kyiv city Web address accessed on 4 August 2007). Estimates based on the amount of bakery products sold in the city (thus including temporary visitors and commuters) suggest a minimum of 3.5 million. "There are up to 1.5 mln undercounted residents in Kiev", Korrespondent, 15 June 2005(Russian)

- ↑ "Kiev". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ "Kiev (Ukraine) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ Magocsi, Door Paul Robert. History of Ukraine – 2nd, Revised Edition: The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press.

- 1 2 (Ukrainian) Виборчі комісії фіксують перемогу опозиційних кандидатів у Києві

- 1 2 Битва за Київ: чому посада мера вже не потрібна Кличку і чи будуть вибори взагалі (in Ukrainian). Kontrakty. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- 1 2 У кожного киянина в голові – досвід Майдану (in Ukrainian). 20 April 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- 1 2 (Ukrainian) Interactive parliamentary election 2012 result maps by Ukrayinska Pravda

(Ukrainian) Election results in Ukraine since 1998, Central Election Commission of Ukraine

Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview, ABC-CLIO, 2008, ISBN 1851099077 (page 1629)

Ukraine on its Meandering Path Between East and West by Andrej Lushnycky and Mykola Riabchuk, Peter Lang, 2009, ISBN 303911607X (page 122)

After the parliamentary elections in Ukraine: a tough victory for the Party of Regions, Centre for Eastern Studies (7 November 2012)

Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe by Uwe Backes and Patrick Moreau, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-36912-8 (page 396)

Party of Regions gets 185 seats in Ukrainian parliament, Batkivschyna 101 – CEC, Interfax-Ukraine (12 November 2012)

UDAR submits to Rada resolution on Ukraine’s integration with EU, Interfax-Ukraine (8 January 2013)

(Ukrainian) Electronic Bulletin "Your Choice – 2012". Issue 4: Batkivshchyna, Ukrainian Center for Independent Political Research (24 October 2012)

Ukraine's Party System in Transition? The Rise of the Radically Right-Wing All-Ukrainian Association "Svoboda" by Andreas Umland, Centre for Geopolitical Studies (1 May 2011)"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-18. - ↑ In 2008, the Oxford English Dictionary included 19 quotations with 'Kiev' and none with any other spelling. This spelling is also given by Britannica and Columbia Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "Resolution of the ukrainian commission for legal terminology No. 5". Ukrainian Commission for Legal Terminology. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ The form "Къıєвъ" (Kyiev) is used in old Rus chronicles like Lavretian Chronicle (Мстиславъ Къıєвьскъıи, Mstislav Kyievski; Къıӕне, Kyiene (Kievans)), Novgorod Chronicles and others.

- ↑ Marshall, Joseph, fl.1770 (1971) [1772]. Travels through Germany, Russia, and Poland in the years 1769 and 1770. New York: Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-02763-X. LCCN 77135821. Originally published: London, J. Almon, 1773, LCCN 03-5435.

- ↑ Holderness, Mary (1823). Journey from Riga to the Crimea, with some account of the manners and customs of the colonists of new Russia. London: Sherwood, Jones and co. p. 316. LCCN 04024846. OCLC 5073195.

- ↑ Embassies of Australia Archived 8 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine., Great Britain, Canada, United States Archived 8 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The list includes NATO, OSCE, World Bank

- ↑ Kyiv Post, the leading English language publication in Ukraine.

- ↑ U.S. Begins to Spell Kiev as Kyiv About.com Geography, Friday 20 October 2006

- ↑ GenocideUKraine – epetition response The National Archives, The official site of the Prime Minister's Office, Friday 31 July 2009

- ↑ "K" – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "Ukrainian names". economist.com.

- ↑ "NYTimes.com Search". nytimes.com.

- ↑ Rabinovich GA From the history of urban settlements in the eastern Slavs. In the book.: History, culture, folklore and ethnography of the Slavic peoples. M. 1968. 134.

- ↑ Wilson, Andrew (2000). The Ukrainians. Unexpected Nation. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08355-6

- ↑ dr. Viktor Padányi – Dentu-Magyaria p. 325, footnote 15

- ↑ "The Pechenegs". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-27., Steven Lowe and Dmitriy V. Ryaboy

- ↑ The Making of Urban Europe, 1000–1994 – Paul M. HOHENBERG, Lynn Hollen Lees, Paul M Hohenberg – Google Břger. Books.google.dk. 2009-06-30. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- ↑ Janet Martin, Medieval Russia:980–1584, (Cambridge University Press, 1996), 100.

- ↑ The Destruction of Kiev, University of Toronto Research Repository

- ↑ The Ukraine – W. E. D. Allen – Google Břger. Books.google.dk. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- ↑ Ukraine: A History – Orest Subtelny – Google Břger. Books.google.dk. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- ↑ Jones, Michael (2000). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 6, c.1300–c.1415. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36290-0

- ↑ Jerzy Lukowski, W. H. Zawadzki (2006). A concise history of Poland. Cambridge University Press. p.53. ISBN 0-521-61857-6

- ↑ Davies, Norman (1982). God's Playground: A History of Poland, Vol. 1: The Origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-05351-8

- ↑ Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine, University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97580-6

- ↑ Т.Г. Таирова-Яковлева, Иван Выговский // Единорогъ. Материалы по военной истории Восточной Европы эпохи Средних веков и Раннего Нового времени, вып.1, М., 2009: Под влиянием польской общественности и сильного диктата Ватикана сейм в мае 1659 г. принял Гадячский договор в более чем урезанном виде. Идея Княжества Руського вообще была уничтожена, равно как и положение о сохранении союза с Москвой. Отменялась и ликвидация унии, равно как и целый ряд других позитивных статей.

- ↑ Eugeniusz Romer, O wschodniej granicy Polski z przed 1772 r., w: Księga Pamiątkowa ku czci Oswalda Balzera, t. II, Lwów 1925, s. [358].

- ↑ Eksteins, Modris (1999). Walking Since Daybreak. Houghton Mifflin. p. 87. ISBN 0-618-08231-X.

- ↑ "The Great Purge under Stalin 1937–38". brama.com. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ↑ Orlando Figes The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia, 2007, ISBN 0805074619 , pages 227–315.

- ↑ Robert Gellately, Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe (Knopf, 2007: ISBN 1-4000-4005-1), 720 pages.

- ↑ Daniel Goldhagen, Hitler's Willing Executioners (p. 290) – "2.8 million young, healthy Soviet POWs" killed by the Germans, "mainly by starvation... in less than eight months" of 1941–42, before "the decimation of Soviet POWs... was stopped" and the Germans "began to use them as laborers".

- ↑ "Babi Yar." Jewish Virtual Library. 2012. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/babiyar.html

- ↑ Andy Dougan, Dynamo: Triumph and Tragedy in Nazi-Occupied Kiev (Globe Pequot, 2004: ISBN 1-59228-467-1), p. 83.

- ↑ Samuel W. Mitcham, The Rise of the Wehrmacht: The German Armed Forces and World War II, Vol. 1 (ABC-CLIO, 2008: ISBN 0-275-99659-X), p. 539.

- ↑ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, "Kiev and Babi Yar," Holocaust Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Design by Maxim Tkachuk; web-architecture by Volkova Dasha; templated by Alexey Kovtanets; programming by Irina Batvina; Maxim Bielushkin; Sergey Bogatyrchuk; Vitaliy Galkin; Victor Lushkin; Dmitry Medun; Igor Sitnikov; Vladimir Tarasov; Alexander Filippov; Sergei Koshelev. "Где в Киеве лучше не купаться " Новости в Киеве – Корреспондент". Korrespondent.net. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ↑ "Urban agglomerations with 750,000 inhabitants or more in 2011 and types of natural risks". United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. April 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ Kottek, M.; J. Grieser; C. Beck; B. Rudolf; F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Кліматичні дані по м.Києву" (in Ukrainian). Central Observatory for Geophysics. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Кліматичні рекорди" (in Ukrainian). Central Observatory for Geophysics. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ "Kiev (Ukraine)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ↑ "Weather and Climate – The Climate of Kiev" (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Cappelen, John; Jensen, Jens. "Ukraine – Kiev" (PDF). Climate Data for Selected Stations (1931–1960) (in Danish). Danish Meteorological Institute. p. 332. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ Klitschko officially announced as winner of Kyiv mayor election, Interfax-Ukraine (4 June 2014)

- ↑ Hrushevsky, M., Bar Starostvo: Historical Notes: XV-XVIII, St. Vladimir University Publishing House, Bol'shaya-Vasil'kovskaya, Building no. 29-31, Kiev, Ukraine, 1894; Lviv, Ukraine, ISBN 5-12-004335-6, pp. 1 – 623, 1996.

- ↑ Сюмар, Вікторія (22 May 2012). "Київ: стратегічна позиція чи "чемодан" без ручки?". Ukrayinska Pravda. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ How relations between Ukraine and Russia should look like? Public opinion polls’ results, Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (4 March 2014)

- ↑ Vilenchuk, S. R.; Yatsuk, T.B. (eds.) (2009). Kyiv Statistical Yearbook for 2008. Kiev: Vydavnytstvo Konsultant LLC. p. 213. ISBN 978-966-8459-28-3.

- ↑ Kudritskiy, A. V. (1982). KIEV entsiklopedicheskiy spravochnik. Kiev: Glavnaya redaktsia Ukrainskoy Sovetskoy Entsiklopedii. p. 30.

- ↑ "There are up to 1.5 mln undercounted residents in Kiev". Korrespondent (in Russian). 15 June 2007. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ According to the official 2001 census data: "Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 | Результати | Основні підсумки | Національний склад населення | місто Киів:". ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 14 January 2010. & "Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 | Результати | Основні підсумки | Мовний склад населення | місто Київ:". ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ↑ "Kiev: the city, its residents, problems of today, wishes for tomorrow.", Zerkalo Nedeli, 29 April – 12 May 2006. in Russian Archived 17 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine., in Ukrainian Archived 17 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "What language is spoken in Ukraine?". Welcome to Ukraine. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- ↑ Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Распределение населения по родному языку и уездам. г. Киев

- ↑ "Ukrainian Municipal Survey, March 2–20 2015" (PDF). IRI.

- ↑ alla levy. "Jewish People Around the World". Archived from the original on 2013-06-29. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Forgotten Soviet Plans For Kyiv Archived 4 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Kyiv Post (28 July 2011) Archived 4 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Workpermit.com. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ↑ Kiev.info. Retrieved 20 June 2006.

- ↑ Kyiv found among greenest cities in Europe, Emirates News Agency (10 December 2009)

- 1 2 The Ukraine, Life, 28 October 1946

- ↑ "Andreyevskiy Spusk". Hotels-Kiev.com. Optima Tours. Retrieved 20 June 2006.

- ↑ "Andreevsky spusk". Kyiv Guide (in Russian). Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2006.

- ↑ "Kiev zoo a 'concentration camp for animals'". CBC news. Associated Press. 23 March 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- 1 2 "Culture and Arts" (in Ukrainian). Kyiv Statistics Office. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ Trophies of Dynamo Archived 18 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. – Official website of Dynamo Kyiv Archived 18 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Kyiv opens host stadium for Euro 2012 final". Kyiv Post. 9 October 2011. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011.

- ↑ "Туристичні потоки". Ukrstat.gov.ua. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- 1 2 "Головне управління статистики м.Києва – Туристичні потоки". Gorstat.kiev.ua. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ↑ Vilenchuk, R. G.; Mashkova, L. O. (eds.) (2010). Kyiv Statistical Yearbook for 2009. Kiev: Vydavnytstvo Konsultant LLC. p. 58. ISBN 978-966-8459-28-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Gross Regional Product" (in Ukrainian). Kyiv Statistics Office. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- 1 2 "Gross Domestic Product" (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Committee. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- 1 2 "Labour Market" (in Ukrainian). Kyiv Statistics Office. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ↑ "Labour Market" (in Ukrainian). Kyiv Statistics Office. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Retail Sales" (in Ukrainian). Kyiv Statistics Office. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- ↑ "Retail Sales" (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Committee. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ "Construction Works" (in Ukrainian). Kyiv Statistics Office. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ "Construction Works" (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Committee. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ "Square Metre Prices in Ukraine". Global Property Guide. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ Santarovich, Andrey (27 May 2011). "Kiev Development Strategy Calls for EUR82 billion in foreign investment" (in Russian). Business Information Network. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Statistical Bulletin (May 2012)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). National Bank of Ukraine. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ "Average Monthly Wage Dynamics" (in Ukrainian). Kyiv Statistics Office. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ↑ "Labour Market Indicators" (in Ukrainian). Kyiv Statistics Office. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ↑ "Foreign Direct Investment" (in Ukrainian). Kyiv Statistics Office. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ↑ "Industrial Production by Economic Activity" (in Ukrainian). Kyiv Statistics Office. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ↑ See also:Kiev University official website. Retrieved 28 July 2006.

- ↑ See also: KPI official website. Retrieved 28 July 2006.

- ↑ See also: Kyiv-Mohyla Academy official website Archived 13 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Archived 13 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 28 July 2006. Archived 13 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ See also: Osvita.org URL accessed on 20 June 2006

- ↑ Vilenchuk, S. R.; Yatsuk, T.B. (eds.) (2009). Kyiv Statistical Yearbook for 2008. Kiev: Vydavnytstvo Konsultant LLC. p. 283. ISBN 978-966-8459-28-3.

- ↑ "The Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine". Nbuv.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ↑ "Collection of Jewish Musical Folklore (1912–1947)". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 16 May 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- ↑ (Ukrainian) Kyiv General Department of Statistics, 2011

- ↑ For a 2004 plan of the Kiev tram, please see mashke.org

- ↑ "Азаров дал добро на строительство кольцевой дороги вокруг Киева – Газета "ФАКТЫ и комментарии"". Fakty.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Вторая кольцевая дорога вокруг Киева обойдется в $5-5,5 млрд. – Последние новости Киева – Однако в направлении окружной дороги уже вся земля выкуплена | СЕГОДНЯ". Segodnya.ua. 27 June 2007. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Азаров прогнозирует начало строительства второй кольцевой дороги вокруг Киева в 2012 году | Новости Киева". Korrespondent.net. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ Kyiv Administration: Roads Are In Poor Technical State Because They Have Reached End Of Their Service Lives And Annual Maintenance Volume Is Low Archived 16 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine., Ukrainian News Agency (12 June 2009) Archived 16 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ (Russian) Archunion.com.ua Archived 6 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 20 June 2006. Archived 6 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Азаров запустил в Киеве городскую электричку | Экономика | РИА Новости – Украина". Ua.rian.ru. 13 August 2012. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Kardeş Kentleri Listesi ve 5 Mayıs Avrupa Günü Kutlaması [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Turkish). Ankara Büyükşehir Belediyesi – Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ "Executive Power of the Baku City" (in Russian). Azerbaijan.az. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ↑ "Sister Cities". Beijing Municipal Government. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- ↑ "Bratislava City – Twin Towns". 2003–2009 Bratislava-City.sk. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ "Chicago Sister Cities". Chicago Sister Cities International. 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ↑ "Orașe înfrățite (Twin cities of Chișinău) [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Romanian). Primăria Municipiului Chișinău. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ↑ "Twin and Partner Cities". The City of Edinburgh Council.

- ↑ "Gemellaggi, Patti di amicizia e di fratellanza" (in Italian). Comune di Firenze. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Twinnings" (PDF). Central Union of Municipalities & Communities of Greece. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ "Kraków – Miasta Bliźniacze" [Kraków – Twin Cities]. Miejska Platforma Internetowa Magiczny Kraków (in Polish). Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Sister and Other Associated Cities". Kyoto General Affairs Bureau. City of Kyoto. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ "Leipzig – International Relations". Referat Internationale Zusammenarbeit, City of Leipzig. Retrieved 2015-01-29.

- ↑ "Partnerstädte". Muenchen.de (official website) (in German). Landeshauptstadt München. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ↑ "Twin Cities". Odense Municipality. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Sister cities of Riga: Kiev (Ukraine)". Riga municipality. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ "LEI Nº 5.919, DE 17 DE JULHO DE 2015 (Art. 2º: § 2º Na Europa: XlV- a Cidade de Kiev, na Ucrânia" (in Portuguese). Câmara Municipal do Rio de Janeiro. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Tbilisi Sister Cities". Tbilisi City Hall. Tbilisi Municipal Portal. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "City-to-city cooperation activities of the City of Vienna". Vienna City Administration. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ "International Relations". Vilnius Municipality. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Miasta partnerskie Warszawy – Strona 6" (in Polish). City of Warsaw. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ (Ukrainian) City council has put an end to the "fraternal" relations with Moscow, The Ukrainian Week (February 1, 2016)

- ↑ "Kyiv breaks twinning relationship with Moscow". Day.

the decision taken due to "military aggression of Russia against Ukraine, Crimea annexation and occupation of the territory of Donetsk and Lugansk regions.

- ↑ "International Cooperation". Official website. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ↑ "Acordos de Geminação, de Cooperação e/ou Amizade da Cidade de Lisboa" [Lisbon – Twinning Agreements, Cooperation and Friendship]. Camara Municipal de Lisboa (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ↑ "Toronto's International Alliance Program". Toronto.ca. October 23, 2000. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Yerevan – Partner Cities". Yerevan Municipality Official Website. © 2005—2013 www.yerevan.am. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- ↑ Kiev Peninsula. SCAR Composite Gazetteer of Antarctica.

External links

- Київська міська державна адміністрація – official web portal of the Kiev City State Administration (Ukrainian)

- Official Kiev tourism portal

| Preceded by Istanbul 2004 |

Eurovision Song Contest Hosts Kiev 2005 |

Succeeded by Athens 2006 |

_in_Ukraine_(claims_hatched).svg.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)