Kearns–Sayre syndrome

| Kearns-Sayre syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | ophthalmology |

| ICD-10 | H49.8 |

| ICD-9-CM | 277.87 |

| OMIM | 530000 |

| DiseasesDB | 7137 |

| eMedicine | article/950897 |

| MeSH | D007625 |

| GeneReviews | |

Kearns–Sayre syndrome (abbreviated KSS), also known as oculocraniosomatic disorder or oculocraniosomatic neuromuscular disorder with ragged red fibers, is a mitochondrial myopathy with a typical onset before 20 years of age. KSS is a more severe syndromic variant of chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (abbreviated CPEO), a syndrome that is characterized by isolated involvement of the muscles controlling movement of the eyelid (levator palpebrae, orbicularis oculi) and eye (extra-ocular muscles). This results in ptosis and ophthalmoplegia respectively. KSS involves a combination of the already described CPEO as well as bilateral pigmentary retinopathy and cardiac conduction abnormalities. Other symptoms may include cerebellar ataxia, proximal muscle weakness, deafness, diabetes mellitus, growth hormone deficiency, hypoparathyroidism, and other endocrinopathies.[1] In both of these diseases, muscle involvement may begin unilaterally but always develops into a bilateral deficit, and the course is progressive. This discussion is limited specifically to the more severe and systemically involved variant.

Signs and Symptoms

Individuals with KSS present initially in a similar way to those with typical CPEO. Onset is in the first and second decades of life.

The first symptom of this disease is a unilateral ptosis, or difficulty opening the eyelids, that gradually progresses to a bilateral ptosis. As the ptosis worsens, the individual commonly extends their neck, elevating their chin in an attempt to prevent the eyelids from occluding the visual axis. Along with the insidious development of ptosis, eye movements eventually become limited causing a person to rely more on turning the head side to side or up and down to view objects in the peripheral visual field.

- Pigmentary retinopathy

KSS results in a pigmentation of the retina, primarily in the posterior fundus. The appearance is described as a "salt-and-pepper" appearance. There is diffuse depigmentation of the retinal pigment epithelium with the greatest effect occurring at the macula. This is in contrast to retinitis pigmentosa where the pigmentation is peripheral. The appearance of the retina in KSS is similar to that seen in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (abbreviated DM1). Modest night-blindness can be seen in patients with KSS. Visual acuity loss is usually mild and only occurs in 40–50% of patients.[2]

- Cardiac conduction abnormalities

These most often occurs years after the development of ptosis and ophthalmoplegia.[2] Atrioventricular(abbreviated "AV") block is the most common cardiac conduction deficit. This often progresses to a Third-degree atrioventricular block, which is a complete blockage of the electrical conduction from the atrium to the ventricle. Symptoms of heart block include syncope, exercise intolerance, and bradycardia

- Other

As characterized in Kearns' original publication in 1965 and in later publications, inconsistent features of KSS that may occur are weakness of facial, pharyngeal, trunk, and extremity muscles, hearing loss, small stature, electroencephalographic changes, cerebellar ataxia and elevated levels of cerebrospinal fluid protein.

Etiology

Kearns–Sayre syndrome occurs spontaneously in the majority of cases. In some cases it has been shown to be inherited through mitochondrial, autosomal dominant, or autosomal recessive inheritance. There is no predilection for race or sex, and there are no known risk factors. As of 1992 there were only 226 cases reported in published literature.[3]

Genetics

KSS is the result of deletions in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) that cause a particular phenotype. mtDNA is transmitted exclusively from the mother's ovum.[4] Mitochondrial DNA is composed of 37 genes found in the single circular chromosome measuring 16,569 base pairs in length. Among these, 13 genes encode proteins of the electron transport chain (abbreviated "ETC"), 22 encode transfer RNA (tRNA), and two encode the large and small subunits that form ribosomal RNA (rRNA). The 13 proteins involved in the ETC of the mitochondrion are necessary for oxidative phosphorylation. Mutations in these proteins results in impaired energy production by mitochondria. This cellular energy deficit manifests most readily in tissues that rely heavily upon aerobic metabolism such as the brain, skeletal and cardiac muscles, sensory organs, and kidneys. This is one factor involved in the presentation of mitochondrial diseases.

There are other factors involved in the manifestation of a mitochondrial disease besides the size and location of a mutation. Mitochondria replicate during each cell division during gestation and throughout life. Because the mutation in mitochondrial disease most often occurs early in gestation in these diseases, only those mitochondria in the mutated lineage are defective. This results in an uneven distribution of dysfunctional mitochondria within each cell, and among different tissues of the body. This describes the term heteroplasmic which is characteristic of mitochondrial diseases including KSS. The distribution of mutated mtDNA in each cell, tissue, and organ, is dependent on when and where the mutation occurs.[5] This may explain why two patients with an identical mutation in mtDNA can present with entirely different phenotypes and in turn different syndromes. A publication in 1992 by Fischel-Ghodsian et al. identified the same 4,977-bp deletion in mtDNA in two patients presenting with two entirely different diseases. One of the patients had characteristic KSS, while the other patient had a very different disease known as Pearson marrow pancreas syndrome.[6] Complicating the matter, in some cases Pearson's syndrome has been shown to progress into KSS later in life.[7]

More recent studies have concluded that mtDNA duplications may also play a significant role in determining what phenotype is present. Duplications of mtDNA seem to be characteristic of all cases of KSS and Pearson's syndrome, while they are absent in CPEO.[7][8]

Deletions of mtDNA in KSS vary in size (1.3–8kb), as well as position in the mitochondrial genome. The most common deletion is 4.9kb and spans from position 8469 to position 13147 on the genome. This deletion is present in approximately ⅓ of people with KSS

Diagnosis

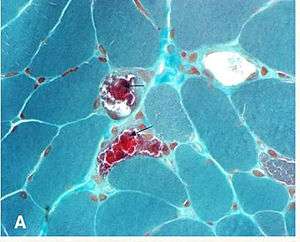

A neuro-ophthalmologist is usually involved in the diagnosis and management of KSS. An individual should be suspected of having KSS based upon clinical exam findings. Suspicion for myopathies should be increased in patients whose ophthalmoplegia does not match a particular set of cranial nerve palsies (oculomotor nerve palsy, fourth nerve palsy, sixth nerve palsy). Initially, imaging studies are often performed to rule out more common pathologies. Diagnosis may be confirmed with muscle biopsy, and may be supplemented with PCR determination of mtDNA mutations. Biopsy findings: It is not necessary to biopsy an ocular muscle to demonstrate histopathologic abnormalities. Cross-section of muscle fibers stained with Gömöri trichrome stain is viewed using light microscopy. In muscle fibers containing high ratios of the mutated mitochondria, there is a higher concentration of mitochondria. This gives these fibers a darker red color, causing the overall appearance of the biopsy to be described as "ragged red fibers. Abnormalities may also be demonstrated in muscle biopsy samples using other histochemical studies such as mitochondrial enzyme stains, by electron microscopy, biochemical analyses of the muscle tissue (ie electron transport chain enzyme activities), and by analysis of muscle mitochondrial DNA. "[9]

Laboratory studies

Blood lactate and pyruvate levels usually are elevated as a result of increased anaerobic metabolism and a decreased ratio of ATP:ADP. CSF analysis shows an elevated protein level, usually >100 mg/dl, as well as an elevated lactate level.[3]

Management and Treatment

Currently there is no curative treatment for KSS. Because it is a rare condition, there are only case reports of treatments with very little data to support their effectiveness. Several promising discoveries have been reported which may support the discovery of new treatments with further research. Satellite cells are responsible for muscle fiber regeneration. It has been noted that mutant mtDNA is rare or undetectable in satellite cells cultured from patients with KSS. Shoubridge et al. (1997) asked the question whether wildtype mtDNA could be restored to muscle tissue by encouraging muscle regeneration. In the forementioned study, regenerating muscle fibers were sampled at the original biopsy site, and it was found that they were essentially homoplasmic for wildtype mtDNA.[5] Perhaps with future techniques of promoting muscle cell regeneration and satellite cell proliferation, functional status in KSS patients could be greatly improved.

One study described a patient with KSS who had reduced serum levels of coenzyme Q10. Administration of 60–120 mg of Coenzyme Q10 for 3 months resulted in normalization of lactate and pyruvate levels, improvement of previously diagnosed first degree AV block, and improvement of ocular movements.[10]

A screening ECG is recommended in all patients presenting with CPEO. In KSS, implantation of pacemaker is advised following the development of significant conduction disease, even in asymptomatic patients.[11]

Screening for endocrinologic disorders should be performed, including measuring serum glucose levels, thyroid function tests, calcium and magnesium levels, and serum electrolyte levels. Hyperaldosteronism is seen in 3% of KSS patients.[12]

History

The triad of CPEO, bilateral pigmentary retinopathy, and cardiac conduction abnormalities was first described in a case report of two patients in 1958 by Thomas P. Kearns (1922-2011), MD., and George Pomeroy Sayre (1911-1992), MD.[13] A second case was published in 1960 by Jager and co-authors reporting these symptoms in a 13-year-old boy.[14] Previous cases of patients with CPEO dying suddenly had been published, occasionally documented as from a cardiac dysrhythmia. Other cases had noted a peculiar pigmentation of the retina, but none of these publications had documented these three pathologies occurring together as a genetic syndrome.[15] Kearns published a defining case in 1965 describing 9 unrelated cases with this triad.[15] In 1988, the first connection was made between KSS and large-scale deletions of muscle mitochondrial DNA (abbreviated mtDNA)[16][17] Since this discovery, numerous deletions in mitochondrial DNA have been linked to the development of KSS.[18][19][20]

References

- ↑ Harvey JN, Barnett D (July 1992). "Endocrine dysfunction in Kearns-Sayre syndrome". Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 37 (1): 97–103. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02289.x. PMID 1424198.

- 1 2 Miller, Neil R.; Newman, Nancy J., eds. (2007). Walsh & Hoyt's Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology: The Essentials. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- 1 2 Kearns-Sayre Syndrome at eMedicine

- ↑ Fine PE (September 1978). "Mitochondrial inheritance and disease". Lancet. 2 (8091): 659–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(78)92764-2. PMID 80581.

- 1 2 Shoubridge EA, Johns T, Karpati G (December 1997). "Complete restoration of a wild-type mtDNA genotype in regenerating muscle fibres in a patient with a tRNA point mutation and mitochondrial encephalomyopathy". Hum. Mol. Genet. 6 (13): 2239–42. doi:10.1093/hmg/6.13.2239. PMID 9361028.

- ↑ Fischel-Ghodsian N, Bohlman MC, Prezant TR, Graham JM, Cederbaum SD, Edwards MJ (June 1992). "Deletion in blood mitochondrial DNA in Kearns-Sayre syndrome". Pediatr. Res. 31 (6): 557–60. doi:10.1203/00006450-199206000-00004. PMID 1635816.

- 1 2 Poulton J, Morten KJ, Weber K, Brown GK, Bindoff L (June 1994). "Are duplications of mitochondrial DNA characteristic of Kearns-Sayre syndrome?". Hum. Mol. Genet. 3 (6): 947–51. doi:10.1093/hmg/3.6.947. PMID 7951243.

- ↑ Miller, Neil R.; Newman, Nancy J.; Bioussee, Valerie; Kerrison, John B. (2008). "Ch. 20, adapted from a chapter 22 by Paul N. Hoffman". Walsh and Hoyt's Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology: the essentials. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 432–6.

- ↑ Rubin, Richard M.; Sadun, Alfredo A. (2008). "Ch. 9.17 Ocular Myopathies". In Yanoff, Myron; Duker, Jason. Ophthalmology (Online Textbook) (3rd ed.). Mosby.

- ↑ Ogasahara S, Yorifuji S, Nishikawa Y, et al. (March 1985). "Improvement of abnormal pyruvate metabolism and cardiac conduction defect with coenzyme Q10 in Kearns-Sayre syndrome". Neurology. 35 (3): 372–7. doi:10.1212/WNL.35.3.372. PMID 3974895.

- ↑ Gregoratos G, Abrams J, Epstein AE, et al. (October 2002). "ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 guideline update for implantation of cardiac pacemakers and antiarrhythmia devices: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/NASPE Committee to Update the 1998 Pacemaker Guidelines)". Circulation. 106 (16): 2145–61. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000035996.46455.09. PMID 12379588.

- ↑ Kearns-Sayre Syndrome~diagnosis at eMedicine

- ↑ Kearns TP, Sayre GP (August 1958). "Retinitis pigmentosa, external ophthalmophegia, and complete heart block: unusual syndrome with histologic study in one of two cases". AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 60 (2): 280–9. doi:10.1001/archopht.1958.00940080296016. PMID 13558799.

- ↑ Jager BV, Fred HL, Butler RB, Carnes WH (November 1960). "Occurrence of retinal pigmentation, ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, deafness and heart block. Report of a case, with findings at autopsy". Am. J. Med. 29 (5): 888–93. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(60)90122-4. PMID 13789175.

- 1 2 Kearns TP (1965). "External Ophthalmoplegia, Pigmentary Degeneration of the Retina, and Cardiomyopathy: A Newly Recognized Syndrome". Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 63: 559–625. PMC 1310209

. PMID 16693635.

. PMID 16693635. - ↑ Zeviani M, Moraes CT, DiMauro S, et al. (September 1988). "Deletions of mitochondrial DNA in Kearns-Sayre syndrome". Neurology. 38 (9): 1339–46. doi:10.1212/wnl.38.9.1339. PMID 3412580.

- ↑ Lestienne P, Ponsot G (April 1988). "Kearns-Sayre syndrome with muscle mitochondrial DNA deletion". Lancet. 1 (8590): 885. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(88)91632-7. PMID 2895391.

- ↑ Carod-Artal FJ, Lopez Gallardo E, Solano A, Dahmani Y, Herrero MD, Montoya J (September 2006). "[Mitochondrial DNA deletions in Kearns-Sayre syndrome]". Neurologia (in Spanish). 21 (7): 357–64. PMID 16977556.

- ↑ Lertrit P, Imsumran A, Karnkirawattana P, et al. (1999). "A unique 3.5-kb deletion of the mitochondrial genome in Thai patients with Kearns-Sayre syndrome". Hum. Genet. 105 (1–2): 127–31. doi:10.1007/s004390051074. PMID 10480366.

- ↑ Soga F, Ueno S, Yorifuji S (September 1993). "[Deletions of mitochondrial DNA in Kearns-Sayre syndrome]". Nippon Rinsho (in Japanese). 51 (9): 2386–90. PMID 8411717.

External links

- kearns_sayre at NINDS

- Kearns Sayre syndrome at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases