Katherine Schmidt

| Katherine Schmidt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

February 6, 1899[1] Xenia, Ohio |

| Died |

April 18, 1978 (aged 79)[2] Sarasota, Florida[1] |

| Known for |

|

Katherine Schmidt (February 6, 1899 – April 18, 1978) was an American artist and art activist. Early in her career the figure studies, landscapes, and still lifes she painted drew praise for their "purity and clarity of color," "sound draftsmanship," and "individual choice of subject and its handling."[3] During the 1930s she was known mainly for the quality of her still life paintings which showed, one critic said, "impeccable artistry."[4] At the end of her career, in the 1960s and 1970s, she produced specialized and highly disciplined still lifes of objects such as dead leaves and pieces of crumpled paper, which, said a critic, approached a "magical realism."[5] As an art activist she helped promote the rights of artists for fair remuneration.[6]

Art training

In 1912, at the age of 13, Schmidt began to take Saturday classes at the Art Students League under the artist Agnes Richmond.[7][note 1] At that time the League was popular with girls and young women who wished to study art and its Saturday classes made it accessible to those, like Schmidt, who were attending school on weekdays.[note 2] While still in high school she, her sister, and two other girls spent part of one summer painting at the art colony in Woodstock, New York. With her sister and another girl she spent the next two summer vacations painting in Gloucester, Massachusetts, then a popular destination for artists. During these trips Agnes Richmond acted as chaperon and guardian.[7][note 3]

In 1917 after graduating from high school Schmidt took regular afternoon classes at the League. By chance she joined the class of Kenneth Hayes Miller, the artist who would most influence her mature style.[6][14][note 4] Schmidt found Miller's teaching style to be emotionally and intellectually demanding. She said that in addition to teaching technique Miller helped each student bring out his or her unique talents and as a result, she said, "all of us were enormously different" in manner of working and artistic style.[7] By giving them group assignments and inviting them to regular Wednesday afternoon teas at his apartment Miller also helped his students become well acquainted with one another.[7][note 5]

During the time she was his student the League abolished its same-sex classroom policy and, mixing more freely with men than she had previously been able to do, Schmidt broadened her circle of friends. To a group of women she had previously befriended she now added a roughly equal number of men.[7][15]:6[note 6] Over the next few decades this group of students would form the nucleus of three others: (1) the "Fourteenth Street school" or "Miller gang" made up of Miller students who rented apartments in the vicinity of his apartment at 30 E. 14th Street, (2) the "Whitney Circle" all of whom were members of the Whitney Studio Club, and (3) the artists attached to two galleries, the Daniel Gallery and, after its demise, the Downtown Gallery.[17][18][19][20] In 1932 Peggy Bacon produced a drypoint print showing the group enjoying themselves at a Third Avenue bowling alley. Entitled "Ardent Bowlers," it showed Alexander Brook, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Reginald Marsh, along with Peggy herself and others of Schmidt's friends.[21] In an oral history interview of 1969 Schmidt named many of the ardent bowlers as her lifelong friends.[7][note 7]

Artistic career

Schmidt became founding member of Whitney Studio Club in 1918.[7][20]:31[note 8] The club welcomed talented young artists such as Schmidt and her friends from the Miller class. Proponents of all artistic styles were welcome and the membership grew quickly as members proposed other artists for membership. In addition to holding group shows, the club held solo exhibitions in separate galleries for two or three members at a time.[15]:8[22] These exhibitions drew favorable reviews from New York critics thus helping Schmidt and the club's other young members, especially the women among them, to advance their careers.[20]:30[note 9] Schmidt later recalled that the young League students in the club were among the first League artists of her time to be given exhibitions.[7][note 10]

In 1919 Schmidt married fellow student Yasuo Kuniyoshi at an artist compound that had been established by Hamilton Easter Field in Ogunquit, Maine. As a patron of young artists, Field had recognized Kuniyoshi's talent and had invited him to spend summers in Ogunquit beginning in 1918. Schmidt met Field through Kuniyoshi and was herself invited to attend. As a wedding present Field gave them the use of a studio in the compound and also gave them an apartment in one of two houses he owned in Brooklyn's Columbia Heights.[7][14][15]:8[24]

1920s

Although both Schmidt and Kuniyoshi were able to sell a few paintings in the early 1920s, they had to take jobs both to support themselves and to save for a planned trip to Europe. Schmidt ran the lunch room at the League during this time and later ran an evening sketch class and performed odd jobs for the Whitney Studio Club.[7][20][23]:60[note 11]

Schmidt and Kuniyoshi spent two years in Europe during 1925 and 1926 and returned there in 1927. Unlike Kuniyoshi and other American artists who traveled in France, Spain, and Italy during the 1920s, Schmidt did not find in those places subjects that she wished to paint and she returned to the United States feeling that the American environment suited her artistic outlook better than the European.[7][note 12]

The Whitney Studio Club had given Schmidt her first solo exhibition in 1923. She and two other artists showed works in three separate galleries.[15]:8[25][note 13] In 1927 Schmidt was given her second solo show, the first of an annual series of them held at the Daniel Gallery.[7][26][note 14] By this time Schmidt's work had become familiar to both critics and gallery goers.[30] Earlier shows at the Whitney Studio Club, the Society of Independent Artists, and a few other galleries had attracted notice from New York art critics, but these reviews were not nearly as comprehensive as the write ups her work received at this time.[note 15] A critic for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Helen Appleton Read, said her work during the early years of her career had showed Kenneth Hayes Miller's influence but was nonetheless "distinctly personal." The paintings in the solo show at the Daniel Gallery were now, she said, less given to Miller-like subjects than they had been.[30] A critic for the New York Times noted an influence of Renoir in the figure studies and praised her ability to capture a sense of drama in her subjects but felt, overall, that her work lacked feeling, was "somewhat dry in aspect."[35]

In reviewing the solo show given her a year later a Brooklyn Daily Eagle critic noticed a continuing improvement in her work. This critic saw little influence of Miller's naïve style, a continuing feeling for texture and color, and, in general, and increasing competency in her work.[36][note 16] Writing about the same show Margaret Bruening of the New York Evening Post mentioned lingering traces of "Kenneth Hayes Millerism," praised Schmidt's self-portrait as "a likeness and a good piece of plastic design carried out in reticence and surety," and said that she "seems to grow quite steadily and triumphantly into her own." One painting, called "Still Life" was to Breuning the highlight of the exhibition. "A real joy to behold," it was, she said, a work of "power and beauty" having "aesthetic emotion" that was lacking in Schmidt's landscapes and figure paintings.[37] The tendency to see increasing strength and maturity in Schmidt's work continued in reviews of her solo show at the Daniel Gallery in 1930 of which one critic pointed to a "a rich and natural realization of her gifts" and said "she is now reaping the artistic reward for this strenuous apprenticeship, in a power and concentration that the more easily satisfied painter does not attain."[38][39]

1930s

Schmidt held her last solo show at the Daniel Gallery in 1931.[40] By then she was seen as primarily a still life painter.[40] One critic found the still lifes in the show to be technically sound but lacking in "soul."[40] Finding in them a "substantial fund of humor," another said they showed an "uncanny skill in surrounding three-dimensional forms with air" and possessed a "mysterious realism."[41] A third critic, Breuning in the Evening Post, saw in them an "astonishing vitality."[3] In 1932 the new Whitney Museum of American Art showed one of Schmidt's paintings in a group exhibition and the following year the museum purchased it.[42][43]

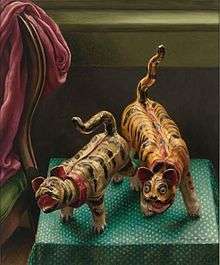

Schmidt began showing at the Downtown Gallery in 1933, following the closure of the Daniel Gallery the year before.[7][19][note 17] Of her first solo show at the Downtown Gallery in 1934, Edward Alden Jewell of the New York Times said she showed a lingering influence of both Miller and Renoir in some figure studies but added "it never does to pigeonhole Katherine Schmidt's art with too much easy confidence." He called her painting, "Tiger, Tiger," humorous, exotic, and, in all, the best work she had done in a long time. Noting her skillful handling of portraits, figure studies, landscapes, and still lifes, he added, "Katherine Schmidt may well be styled the Ruth Draper of the art world."[45][note 18] Writing that "she has by no means attained the position as one of the foremost painters of the younger generation that she deserves," a critic for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle called this show "one of the outstanding exhibitions of the year."[48] Schmidt continued to receive thoughtful reviews of both solo and group shows held at the Downtown Gallery, the Whitney Museum, and other venues in the middle and late 1930s.

Fellow artist, friend, art historian, curator, and critic, Lloyd Goodrich said that Schmidt's technical command increased during the early 1930s and this command was most apparent in her still life work: "Every object was modeled with a complete roundness and a sensation of solidity and weight... The relations of each element to the others, and to the space in which they were contained, were clearly understood. The result was finely conceived, closely knit design. Color was full-bodied, earthy, neither sweet nor brilliant."[15]:8 At this time she began to make figure studies of the Depression's victims and for portraying these subjects Edward Alden Jewell wrote that she was "the right artist for the right task." Describing the paintings in a 1939 solo show at the Downtown as "delightfully congruous," he said they revealed "a charming, subtle style that has ripened and that has real stature."[49] Goodrich described one of these figure studies, "Broe and McDonald Listen In," as different from "the idealized pictures of the proletariat common at the time" and said "every element" of the painting "played its part as form, even Broe's shirtsleeves, whose folds were as consciously designed as the draperies in old masters."[15]:12[note 19]

1940s, 1950s, and 1960s

After 1939 Schmidt produced less work and although she appeared in group shows she gave no further solo exhibitions until 1961.[15] During the war years she produced an atypical painting, "Home," evoking patriotic sentiments. Noting that it was a marked departure from the aesthetic distance she had previously maintained, a critic called this work "almost religious."[50][note 20]

Toward the end of the 1930s Schmidt had begun to feel dissatisfied with her work in general and particularly with her technique.[15][note 21] To solve the problem she returned to fundamentals. Using a German text that her husband translated for her, she slowly rebuilt her skills over the next two decades.[note 22] The book was Max Doerner's Malmaterial und seine Verwendung im Bilde.[note 23] She said: "The reading of the Doerner book was very important personally to me. It took me years to understand the technique really, I mean the meaning of it."[7] Doerner called for a disciplined approach to painting. Deploring what he saw as a modern tendency for artists to use a "free and easy technique untrammeled by any regard for the laws of the materials," he called for "systematically constructed pictures" produced by "clearly thought-out pictorial projects, where every phase of the picture is developed almost according to a schedule."[51]:337[note 24] In 1960 she found a new focus for her art. Capitalizing on the strength she had previously shown in still lifes and employing the disciplines she learned from Doerner, she began to use a naturalistic approach which, as one critic said, approached a "magical realism."[2]

Her decision to work in a new style was sudden. She said: "One day I washed my hands. My waste basket wasn't right there so I threw the paper towel down on the table. Later when I went back into this little room I had in the country, there was this piece of paper lying there. I thought, "Oh, my, that's beautiful." And I painted it."[7] Her new work was precise and realistic almost to the point of trompe-l'œil.[15]:8 Her subjects were ordinary objects of no obvious beauty, crumpled paper and dead leaves. Using what one critic called a "neat and painstaking draftsmanship,"[5] she made pictures which one critic found to contain "an almost pre-Raphaelite intensity."[52] Her method was slow and methodical. She built up each painting systematically over as many as five months. As a result, it took her a long time to accumulate enough new work for a gallery exhibition.[7] She had used objects such as these in some of her earlier still lifes but never as the main element of a painting. Lloyd Goodrich said that in paintings like "Blue Paper and Cracker Boxes" Schmidt was able to give "movement and life" to the "unsubstantial, immobile" objects she painted and concluded that her paintings at this time "within their severely limited content, achieved the purest artistry of all her works."[15]:18[note 25]

Schmidt respected and admired the work of abstract and non-objective artists, but she never felt inclined to work in that style. In 1969 she said

I never have liked to work from my imagination. I like to work from a fact, and I will try to make something out of the fact. I enjoy that most. And I do my best work when I do that. I don't know whether it's just because I put it out of my mind that I don't like to make things up. Some artists are marvelous at just fantastic inventions. But I love the smell and the feel of life. You have to follow your appetites. You don't choose to be what you are. You are what you are.[7]

During the 1960s and 1970s Schmidt showed at the Isaacson, Zabriskie, and Durlacher Galleries, in exhibitions that appeared, as she said, pretty much as she pleased.[5][7][52][53] During the 1970s her output diminished up to her death in 1978.[2]

Exhibitions

Schmidt's work appeared most frequently in group and solo shows held in the early 1920s by the Whitney Studio Club, in the later 1920s by the Daniel Gallery, in the 1930s by the Downtown Gallery and the Whitney Museum of American Art, and in the 1960s and 1970s by the Isaacson and Durlacher Galleries. In addition to these shows, Schmidt's work appeared in group exhibitions at A.W.A. Clubhouse, An American Group, Inc., Art Students League, Associated American Artists, Brooklyn Society of Modern Artists, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, Penn., Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C., Grand Central Galleries, J. Wanamaker Gallery of Modern Decorative Art, New York World's Fair, 1939, Newark Museum, Newark, N.J., Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Penn., Pepsi Cola Portrait of America Exhibit, Society of Independent Artists, and Salons of America. She appeared in solo exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, Newark Museum, University of Nebraska, and Zabriskie Gallery.[note 26]

Collections

Schmidt's work has been widely collected American museums, including the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, Newark Museum (Newark, N.J.), Santa Barbara Museum (Santa Barbara, Cal.), Sata Roby Foundation Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, D.C.), University of Arizona, Weatherspoon Art Museum (University of North Carolina at Greensboro), and Whitney Museum of American Art. Unless otherwise indicated, these museums are in New York.[note 27]

Art activism

During the early years of her career Schmidt joined the Society of Independent Artists and the Salons of America as well as the Whitney Studio Club and these connections suggest a liberal, or as it was then termed, radical attitude toward art and artists.[54] Wishing to further the careers of young American artists, these organizations aimed to counter the conservative practices of the National Academy of Arts and Sciences by holding exhibitions free of juries and prizes and offering works for sale without commission.[7][14][54][note 28] They engaged the New York public with advertising and with publicity campaigns having slogans such as "what is home without a modern picture?" In joining them Schmidt placed herself among the progressive and independent artists of the time.[22]

In 1923, the same year in which she was given a solo show at the Whitney Studio Club, Schmidt's work appeared in the New Gallery on Madison Avenue. The gallery was then it its inaugural year, she was one of the few women included in its roster, and a painting of hers achieved what was probably her first commercial sale.[56][57][note 29] It may be more significant, however, that the New Gallery had published a strongly-worded manifesto which aligned it with the club as a liberal force in the New York art world. The statement said the gallery was "an experiment to ascertain whether there is a public ready to take an interest in contemporary pictures which are something more than slick and servile patterns of the past"[57]:2 and it envisioned the formation of a society of artists who agreed with its goals.[57]:5[note 30] To accomplish this vision the gallery formed a club made up of artists and gallery patrons of which Schmidt became a member.[57]:2

In the early 1930s Schmidt participated in another organization devoted to the support of art in contemporary American culture, and on behalf of that organization she led an effort to convince museums that they should compensate artists through rental fees when they exhibited works without purchasing them. The organization was the American Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Gravers and her position was chair of the Committee on Rentals.[15][58][59][note 31] Despite repeated requests and an intense publicity campaign most museums refused to pay the requested rental fees. The controversy reached a peak when many artists refused to participate in a show at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh and it dwindled out after the museums and several influential art critics refused to budge.[59][62][63][64][note 32]

In the mid-1930s Schmidt and Kuniyoshi had what proved to be an amicable divorce and, believing herself happily independent, she was surprised to find herself in love. Her second husband was Irvine J. Shubert who would become a lifelong companion. Because Shubert made a good living as a lawyer, she did not experience the financial straits which afflicted many other artists in those times. All the same she became a strong supporter of government support of the arts and when it was announced that the Federal Art Project would be shut down she joined Alfred Barr and others in giving testimony before a congressional committee to urge its continuance.[7][15] After its demise she helped draw up a plan by which New York State would purchase works by artists for use in public buildings and for exhibitions that would circulate to public buildings and community centers. Although the effort did not succeed, it helped inspire the state's Council on Arts some years later.[15] Of her involvement in arts activism Schmidt later said, "I enjoyed very much doing that kind of thing. I had been freed from a lot of responsibilities and I had the time to do it."[7]

Personal life

Schmidt was born on February 6, 1899, in Xenia, Ohio.[1] Both her parents had been born in Germany having emigrated to the United States following the turmoil of the German revolutions of 1848–49. They named her after a maternal aunt whose amateur painting would help Schmidt find her own love of art.[7] She had one sibling, Anna, who was a year younger.[7][note 33] Before she was ten her family moved to New York City.[note 34] There she attended local public schools and was still a high school student when she started attending Saturday afternoon classes at the Art Students League.[note 35]

Schmidt met Yasuo Kuniyoshi in 1917 while studying at the League. When they married two years later Schmidt's parents cut her off from the family and formally disowned her, causing her to lose American citizenship.[7][14][note 36] Because Kuniyoshi had little income and Schmidt none, they were fortunate to have been supported by Hamilton Easter Field's gift of places to stay during the winter at a house he owned in Brooklyn and during the summer in a small studio he had built in Ogunquit. While the summer place proved to be temporary, the apartment in Brooklyn was theirs to use, free of payment, from the time they married until their divorce in 1932.[7][14] Despite careful budgeting of limited finances, they both had to take jobs, Schmidt as director of a sketch class at Whitney and as informal assistant to Juliana Force and Kuniyoshi as frame-maker and art photographer. They were able to earn enough to support a ten-month trip to Europe over 1926 and 1926, a return trip in 1928, and the purchase of a house in Woodstock, N.Y., in 1932.[7][15]:11[note 37]

They returned to France in May 1928 but Schmidt came back to New York early saying the French influence did not suit her and that she was most comfortable with what she called "American corn."[7] After they had begun spending their summers in the Woodstock house she found that managing it and providing hospitality to the many guests they were expected to entertain kept her from making art.[7][15]:11[note 38]

When Kuniyoshi and Schmidt divorced in 1932 she stopped spending her summers in Woodstock. Although she was upset about Kuniyoshi's failure to treat her as an equal, the divorce was not acrimonious and the two remained friends. She was at his bedside when he died in 1953 and subsequently remained on good terms with his wife Sara.[7][14][note 39] Soon after the divorce she was befriended by a young lawyer with artistic inclinations and the following year they married. They lived in Greenwich Village for some years, but after he became a vice president for a large hotel chain, they moved to a hotel apartment. She welcomed the change because it was time-consuming and frustrating for her to maintain an old townhouse during wartime labor shortages and apartment living gave her more time to paint and draw.[7][15]:11

Her new husband, Irvine J. Shubert, had been born in Austria in 1902.[72] His family emigrated to New York in 1910 and he became a lawyer on graduating from Columbia University Law School in 1925.[73][note 40]

Schmidt was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1964. Two operations and a long recovery period reduced the time she could devote to painting and drawing. She nonetheless remained at work and survived until 1978 when she died of a recurrence of cancer.[2][15]:18[note 41]

Other names

Schmidt used Katherine Schmidt as her professional name throughout her career. An exception appeared in 1921 when she showed in the fifth annual exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists as "K. Kuniyoshi." In transacting business and performing community service functions she was sometimes known by either of her married names, Kuniyoshi or Shubert.[15][54]

Notes

- ↑ Agnes Richmond, (1870–1964) began taking Saturday classes at the Art Students League in 1888. She won a scholarship prize for a figure study in 1903 and from 1910 to 1916 was an instructor at the school. She painted figure studies, mainly realistic portraits of women in front of urban or rural outdoor backgrounds, and her style resembled that of John Sloan. As a teacher she would advise students not to follow any teacher's ideas too closely but to look within themselves to develop their own individual styles.[8][9][10]

- ↑ Founded in 1875, the Art Students League was a pay-as-you-go cooperative endeavor that gave classes but did not have a course of study and granted no degrees. Conceived by and for the art students themselves, its administration was composed of League members and included both men and women. Based on the Parisian atelier model, its instruction was informal. Students were expected to seek out the instructors who would best meet their needs. The League's aim of developing "unselfish and true friendship" among its students was achieved as many of those who took classes in the period during which Schmidt attended became lifelong friends.[11][12][13]

- ↑ Schmidt later recalled that Richmond watched over the girls to keep them from scandalous association with the local artists. They kept to themselves the whole time, although Schmidt recalled that in Woodstock she did cause comment by forming an acquaintance with a local man, Shamus O'Shield.[7]

- ↑ When Schmidt started taking weekday classes at the League there were separate classes for men and women, the men in the evening and the women in the afternoon. Many classes involved drawing live models, generally nudes, and her first class was one such life class taught by the lithographer, Louis Maurer. She recalled that she did not learn anything useful from him. She also took classes from George Bridgman and John Sloan. She had hoped to study under George Bellows, but, due a mistake in payment of the fee, she found she could not and thereupon joined Miller's class which was being taught next door.[7]

- ↑ Miller would give Schmidt and his other students lists of paintings by the old masters to examine at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the group would spend their Sunday afternoons carrying out these assignments.[15][16] Schmidt called Miller's teas his "Wednesday afternoons." She said Miller expected his students to show up for them.[7]

- ↑ She and other participants recalled that Peggy Bacon, Isabel Bishop, Arnold Blanch, Lucile Lundquist Blanch, Alexander Brook, Betty Burroughs, Edmund Duffy, Lloyd Goodrich, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Dick Lahey, Molly Luce, Reginald Marsh, David Morrison, Lloyd Parsons, Ann Rector, Henry Schnakenberg, and Dorothy Varian belonged to this artistic clique.[7][15]:6[16]

- ↑ The interview is part of the oral history program of the Archives of American Art. It was conducted by the art historian, Paul Cummings, in December 1969. In it Schmidt listed artists from the Miller class with whom she had maintained social contact over the years. The list included Peggy Bacon, Isabel Bishop, Arnold and Lucile (Lundquist) Blanch, Alexander Brook, Betty Burroughs, Lloyd Goodrich, Dorothy Greenbaum, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Molly Luce, Reginald Marsh, David Morrison, Lloyd Parsons, Ann Rector, Henry Schnakenberg, and Dorothy Varian.[7]

- ↑ A project of the collector, sculptor, and philanthropist, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the Whitney Studio Club provided a gallery to exhibit work produced by its members, a studio for sketch classes, and space for social gatherings. With Juliana R. Force as director, the Club began in 1918 and continued until 1928 when it was superseded by the Whitney Studio Gallery, which itself was superseded in 1930–31 by the Whitney Museum of American Art.[22] The club was known for helping to provide recognition for young artists and one of these artists, Raphael Soyer said the club was the "main gateway to an art career."[23]:72

- ↑ Schmidt was one of the club's founding members, as were Dorothy Varian, Nan Watson, Peggy Bacon, and Mabel Dwight. Others who joined later included Isabel Bishop, Molly Luce, and Anne Goldthwaite.[20]:20

- ↑ In the oral history interview she gave in 1969 she said, "I suppose at the League we belong to what would be known as the swinging group; I mean we were the first of the younger group to have shows, and so on. You see, there was quite a group in that period of the early 1920s or just before the twenties; it was before the twenties because we were all out [of League classes] by that time."[7]

- ↑ In 1969 Schmidt described her daily routine in the years when she ran the League lunchroom: "I used to get up at five o'clock in the morning... We had just one room at that time and I'd paint at one end of the couch and Yas would paint the other. But there was a certain amount of house work to do. Then I had to be at the League at ten o'clock. Then there was the lunch. I had to sit at the cash register. I had to order food. I had to plan the menu for the next day. Then I had a few hours off in the afternoon when I could go out for a walk. Then there was dinner at night."[7]

- ↑ In the oral history interview of 1969 she said "I would go out and walk for miles and never find anything to paint. The idiom was wrong. It didn't look natural. It wasn't right.[7]

- ↑ The other two artists were Alexander Altenburg and L. William Quanchi.[25]

- ↑ The Daniel Gallery had opened in 1913. Run by Charles Daniel, with help from Alanson Hartpence, it showed the work of young American artists such as Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Rockwell Kent, Maurice Prendergast, and Man Ray.[7][27][28] One of the relatively few galleries that showed art by women, its stable of artists included many of Schmidt's friends from the Art Students League and Whitney Studio Club.[7][27][28][29]

- ↑ For example, regarding a group show held at the New Gallery in December 1923, an article in the New York Times said "It would be a pleasure to quite physically balance in one's hand the color and arrangement of Katherine Schmidt's still life flowers."[31] In January and February of 1924 her work was singled out for comment within group shows at the Whitney Studio Club and Wanamaker department store gallery, respectively.[32][33] In 1925 she was listed among artists who arranged for their own group show at a New York bookstore.[34]

- ↑ This review of the 1928 exhibition in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle was accompanied by a photo of "Portrait of Reginald Marsh" by Schmidt.

- ↑ Owned by Edith Halpert, the Downtown Gallery, like the Daniel Gallery, specialized in the works of contemporary American artists, including women. In addition to Schmidt and some of her friends its artists included Stuart Davis, Georgia O'Keeffe, Arthur Dove, Jacob Lawrence, Charles Sheeler, David Fredenthal, Ben Shahn, and Jack Levine.[44] The list of Schmidt's friends who exhibited at the Downtown includes Bacon, Brook, Fiene, Goldthwaite, Karfiol, Kuniyoshi, Laurent, Spencer, Varian, and the Zorachs.[19][29]

- ↑ Ruth Draper was a monologist famed for her one-woman shows. During her career she created thirty-seven sketches and fifty-eight characters which she performed with success in the United States and Europe as well as across Africa, Asia, Australia, and South America.[46] In 1932 a New York Times drama critic said: "The proof of Miss Draper's artistry—if such is needed—is the manner in which she creates and elaborates not only the character of the person whom she personifies on the stage but also the characters of those invisible persons with whom she comes into intangible contact. It is a difficult accomplishment—the success of which depends as much upon the writing of her sketches, which she herself does, as upon the acting of them.[47]

- ↑ Walter Broe became a friend of Schmidt's and others of her artist friends. He was a New York derelict who, she said, "appealed to me as a subject to be painted. He interested me not only for the special qualities which he had as an individual but for the symbolic character which to me he represented as well. Ill-used by life, Walter needed warmth, and he wanted something in his life which would give value. The fact that some of us instinctively liked him and used him stirred Walter deeply. He became devoted to us. The pictures we painted became his pictures. He watched over them, helped prepare them, indeed, he began to watch over and take care of us. His life became meaningful... Walter is more than a model. He is a devoted co-worker."[15]:12

- ↑ The subject of the painting was a wood frame building portrayed in a "cloud of light such as the old painters used to reserve for their saints," which symbolized a "feeling toward the home now in many a heart, a feeling that will continue to grow in the grim days still ahead."[50]

- ↑ In 1969 Schmidt said was discouraged by what she perceived as a change in artistic taste which made her work less desirable. She felt she was not realizing her full potential and could not discover how to move forward. She became disenchanted with the hurly burly of galleries, collectors, prize-winning, and pursuit of sales. Adding to these issues, she was distracted by personal concerns; her responsibilities to her ailing mother and the hard work of running the three residences that she and her husband owned.[15]

- ↑ In 1969 she said "Well, then I studied techniques very hard. This was in the 1940s, in the 1950s.[7]

- ↑ Originally published in 1921, Malmaterial und seine Verwendung im Bilde was reissued in reprints and new editions for many years. An English-language edition appeared as early as 1934 (The Materials of the Artist and Their Use in Painting, New York, Harcourt, Brace and Co.),[51] but Schmidt was apparently unaware of its existence. Friends had bought a copy of the German edition while traveling in Europe. Schmidt's husband, Irvine Shubert, translated it for them, reading out loud to a group of artists who would take notes.[7]

- ↑ Doerner wrote: "We shall see what infinite pains were taken by the old masters in the selection and preparation of their materials. It strikes one as curious, to say the least, when one hears modern artists insist upon their favorite superstition that originality and personal expression are better safeguarded by the use of a free and easy technique untrammeled by any regard for the laws of the materials... Through changing times and techniques, however, one basic idea persists: systematic construction, with a concurrent division of treatment of form and color as two distinct phases of the process. .. [The old masters worked on] clearly thought-out pictorial projects, where every phase of the picture is developed almost according to a schedule. Obviously it is not a technique for quick studies, but only for systematically constructed pictures; and it is exactly in this manner that it was used by the old masters. It is not for everyone, because it presupposes a thorough disciplinary training."[51]:337

- ↑ Goodrich said the crumpled paper in her paintings "assumed all kinds of fantastic shapes, suggesting flames, the crust of the earth, mountain ranges — but beautiful in itself... Crumpling produced innumerable ridges and valleys, facets that caught the light; and the play of light and shadows was depicted with the utmost precision, and with that command of light that can be one of the beauties of realistic painting.[15]:16–17

- ↑ This brief compilation comes from contemporary news sources, including the New York Times, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, New York Evening Post, and New York Sun, as well as online art galleries and the book, The Katherine Schmidt Shubert bequest and a selective view of her art (Whitney Museum of American Art, 1982).[15]

- ↑ This brief compilation comes from contemporary news sources, as well as online art galleries and the book, The Katherine Schmidt Shubert bequest and a selective view of her art (Whitney Museum of American Art, 1982).[15]

- ↑ In 1922 by Hamilton Easter Field founded Salons of America to give artists an alternative to the Society of Independent Artists which he felt unfairly was giving preferential treatment to some of its members. He wholly endorsed the "no prizes, no juries" policy of the society but disliked the preference given to some artists in its advertising and the hanging of its shows. A reporter said he aimed "to give equal opportunity to every member, whether he or she be a conservative or a post-Dadaist." To this end its exhibitions were hung in alphabetical order by artist surname.[55]

- ↑ The New Gallery was founded by a successful lawyer and aspiring artist, James N. Rosenberg. It specialized in showing the work of artists, both American and foreign whose names had not yet become well known in the art community. Of the thirty seven artists who showed in the New Gallery's inaugural year only five were women. In addition to Schmidt they were Gladys Roosevelt Dick, Edith Haworth, Lorna Reid, and Marguerite Zorach. The work that Schmidt sold was an untitled modernist portrait of a seated young woman painted in the style of Kenneth Hayes Miller.[57]

- ↑ The gallery aimed to "encourage those living artists who are not merely clever imitators, skillful draftsmen, facile copyists, but who are laboriously and bravely working out their own problems, nor does it make a secret of the fact that one of the purposes in the creation of The New Gallery Art Club has been to enable those men and women who sympathize with the views of the Gallery, to form a society which shall help to accomplish these ends."[57]:5

- ↑ The American Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Gravers (also called the Society of American Painters, Sculptors, and Gravers) was founded in 1919 in opposition to the National Academy of Design, was restructured in 1922 as the New Society, and, in 1930, restructured again under its original name. During the 1930s its members included prominent liberal artists and its stated purpose was to "give purpose and direction to the plastic and graphic arts" by means of a "flexible and progressive" organization that was "more in tune with temper and aspirations of the times" than others. Many of Schmidt's friends were members of the society and some joined her in various positions of leadership. Like the Whitney Studio Club and the New Gallery, the society held exhibitions of its members' works.[15][58][60][61]

- ↑ In 1969 Schmidt said: "The Painters, Sculptors and Engravers was very interesting historically because it was formed really to help American art grow its own legs; and also to counteract the terrible influence of the Academy... I've been asked to join the Academy several times... But I never would join."[7]

- ↑ Educated at Barnard College, Anna became an actress associated with the Neighborhood Playhouse (a part of the Henry Street Settlement, it was later called Henry Street Playhouse, and then Harry De Jur Playhouse). She used the name Ann, or Anne, Schmidt and is remembered for her performance in The Grand Street Follies.[7][65]

- ↑ In 1910 the Schmidt family lived near Columbia University at 406 Hamilton Place. Schmidt's father was then a washing machine salesman.[66] Ten years later Schmidt's parents and Anna were living at 96 Riverside Drive and he was proprietor of a laundry.[67]

- ↑ Schmidt remembered their neighborhood on the upper east side of Manhattan as middle-class, easy-going, and quite cosmopolitan. She attended PS 186 on 145th Street. Although the building has been derelict for years, that school was then "the architectural and academic pride of the community." (The quote comes from the web site of a community coalition devoted to restoration of the building.)[7][68]

- ↑ Because Kuniyoshi had been born in Japan and had not obtained U.S. citizenship, Schmidt was considered to be a Japanese national after her marriage. Some years later she regained U.S. citizenship through naturalization proceedings.[69][70]

- ↑ In 1969 Schmidt spoke about their financial problems: "We had a very hard time. You see, my family disowned me when I married Yas. So that we had a hard time earning a living. I had never done a thing. I didn't know what to do with a carrot when I was first presented with one. But I soon learned. We had to earn a living and at that time it was very hard to do so."[7] Of the scrimping they did during their first trip to Europe she said, "We were there for one year. And we went with friends, Camby Chambers, Esther Andrews, and Sue Lawson who was the wife of the playwright Howard Lawson. They were going over to meet Hemingway. They were very good friends of his. Yas and I were really shocked. We thought these people lived too high, you know, drank too much wine, did too much . . . and we couldn't afford it. We had a very hard time."[7]

- ↑ The Woodstock house was at 194 Ohayo Mountain Road. To pay for its construction they used what remained of their savings plus money from a small inheritance Schmidt had received. To reduce costs they did much of the finishing work themselves. Schmidt later said, "We had nothing but friendly assistance from most of the people we knew. This house we built was only a summer house... I found that living in that kind of atmosphere—I being the woman of the house—the responsibilities of providing food, having people come up for weekends. For me every weekend was a nightmare. Because who knew who was driving up from New York. People would drive up and there they were. They simply appeared. And getting dinner—well, it still takes me a whole day, or a day and a half to prepare a proper dinner. And then a day to clean up. And while I was a very strong, healthy young woman I resented all the time that had to be spent this way.[7]

- ↑ Kuniyoshi died of cancer in New York and was buried in Woodstock in May 1953.[71] Schmidt said of their relationship after the divorce: "You know, we were close to him until he died. He was very dependent on Irvine and myself in many ways. While he was dying I went to the hospital every day. He wanted me to be there; I felt that he did. And also I felt that I was helpful to Sara, I mean to sit through that long, awful business."[7]

- ↑ The record for the Shubert family in the U.S. Census of 1920 states that Irvine was then a student while his three older sisters and niece who was living with them were all at work as operators in the garment trade. Irvine's father was a dealer in groceries who spoke Yiddish but not English.[73] In the 1940s Shubert became the general manager and vice president of the Sheraton Corporation. When he retired in 1961 he was chairman of the board of Thompson Industries Inc.[74]

- ↑ She died in Sarasota, Florida, where they resided, while also maintaining a home in Little Compton, on the Rhode Island shore.[2][7][75]

References

- 1 2 3 "Katherine Schmidt, Jan 1978". "United States Social Security Death Index," database, FamilySearch; citing U.S. Social Security Administration, Death Master File, database (Alexandria, Virginia: National Technical Information Service, ongoing). Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Katherine Schmidt, Artist Worked in Oils, Pencil, Charcoal and Chalk Notes". New York Times. 1961-01-20. p. B10.

- 1 2 Margaret Breuning (1931-02-28). "One-Man Exhibitions Feature the Current Week's Calendar of Art". New York Evening Post. p. D5.

- ↑ A.Z. Kruse (1939-03-19). "At the Art Galleries; Downtown Gallery; Katherine Schmidt". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Stuart Preston (1978-01-20). "Art: Typical Variety: Still-Lifes, Oils, Water-Colors and Italian Figure Sculpture Displayed". New York Times. p. 25.

- 1 2 "Katherine Schmidt". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 "Oral history interview with Katherine Schmidt, 1969 December 8–15". Oral Histories; Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ↑ "Agnes Richmond – Artist, Fine Art Prices, Auction Records for Agnes Richmond". askart.com. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ Alice Cogan (1936-01-12). "Pick Artist Spouse and Learn to be Happy Though Married, Agnes Richmond and Winthrop Turney Tell Brooklyn Youth". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. p. 14B.

- ↑ Marian Wardle; Sarah Burns (2005). American Women Modernists: The Legacy of Robert Henri, 1910–1945. Rutgers University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-8135-3684-2.

- ↑ "An Art Students' League". New York Times. 1875-07-26. p. 8.

- ↑ "The Art Students' League". New York Times. 1876-11-21. p. 8.

- ↑ Holland Cotter (2005-09-09). "A School's Colorful Patina". New York Times. p. B10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Katherine Schmidt; Circle of Friends – The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Lloyd Goodrich (1982). The Katherine Schmidt Shubert bequest and a selective view of her art. Whitney Museum of American Art. ISBN 0-8014-8742-0.

- 1 2 "Oral history interview with Peggy Bacon, 1973". Oral Histories; Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "Figure Study: The Fourteenth Street School and the Woman in Public". University of Virginia Art Museum – Exhibitions – Archive – 2011 – Fall. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- ↑ "Kenneth Hayes Miller". Museum of the City of New York –. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- 1 2 3 Edward Alden Jewell (1933-10-26). "Art in Review; Various "Regulars" Exhibit in a Group Show at the Downtown Gallery". New York Times. p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Janet Wolff (2003). AngloModern: Painting and Modernity in Britain and the United States. Cornell University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-8014-8742-0.

- ↑ Kathleen Monaghan (1986). City life : New York in the 1930s : prints from... by Whitney Museum of American Art. City life : New York in the 1930s : prints from the permanent collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Whitney Museum of American Art. p. 11.

- 1 2 3 The Whitney Studio Club and American Art, 1900–1932. Whitney Museum of American Art. 1975.

- 1 2 Ellen Wiley Todd (1993). The "new Woman" Revised: Painting and Gender Politics on Fourteenth Street. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07471-2.

- ↑ "Jasus Kuniyoshi and Katherine Schmidt, 02 Sep 1919". "Maine, Marriage Index, 1892–1966, 1977–1996," database, FamilySearch; citing Marriage, Maine, United States, State Archives, Augusta. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- 1 2 "Display Ad: Whitney Studio Club". New York Times. 1923-02-04. p. 7.

Paintings by Alexander Altenburg and L. William Quanchi and Katherine Schmidt

- ↑ "Seen in the New York Galleries". New York Times. 1927-01-30. p. X9.

- 1 2 "Man With a New Method". New York Press. 1914-01-25. p. 8.

- 1 2 Robert M. Austin (11 December 1992). American Salons : Encounters with European Modernism, 1885–1917. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-19-536220-6.

- 1 2 Michael Kimmelman (1994-01-07). "Review/Art; An Early Champion of Modernists". New York Times. p. C27.

The list of artists, diverse and impressive, includes Man Ray and Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Stella and Marsden Hartley, Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler, Peter Blume and Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Marguerite Zorach and William Zorach, Raphael Soyer and Glenn O. Coleman.

- 1 2 Helen Appleton Read (1927-02-06). "News and Views on Current Art". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. p. E7.

- ↑ "Art Exhibitions for the Week". New York Times. 1923-12-23. p. 17.

- ↑ "Art Exhibitions for the Week". New York Times. 1924-01-27. p. X12.

- ↑ "Art Exhibitions for the Week". New York Times. 1924-02-10. p. X10.

- ↑ "News and Views on Current Art; Artists Manage Own Gallery". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1925-01-25. p. 2B.

- ↑ "Seen in the New York Galleries". New York Times. 1927-01-30. p. X10.

- ↑ "Peggy Bacon's Pastel Portraits Are Feature of Her Exhibit at the Intimate Gallery; Katherine Schmidt's Exhibit". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1928-04-01.

- ↑ Margaret Bruening (1928-03-31). "Paintings by Charles Burchfield at the Montross Gallery—Recent Canvases by Katherine Schmidt at Daniel's—Other Notes and Comment". New York Evening Post. p. 14.

The handsome "Still Life," however, compensates for any such disappointment. Its power and beauty mark it as the real achievement of the whole exhibition. Each accent of color, each detail of linear pattern or spatial design contributes so definitely to the harmony of the whole canvas that it is a real joy to behold. It is strange that in this purely formal arrangement of subject matter more aesthetic emotion seems to get through than in the landscapes or figure paintings. It is one of the "fair" rewards of the week's gallerying.

- ↑ "Katherine Schmidt and Peggy Bacon Show Recent Work". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1929-03-31. p. E7.

- ↑ Lloyd Goodrich (1933-10-26). "Seen in the Galleries". New York Times. p. 113.

Miss Schmidt has always traveled a difficult road in art, abjuring all pleasing allurements, all entertaining subject-matter, all technical flourishes, and has concentrated on the more difficult and important matter of the mastery of form and color. She nas never been content to leave things vague and undefined, but has painted absolutely, concretely and definitely, even when, as in some of her earliest work, this meant painting unbeautifully. She is now reaping the artistic reward for this strenuous apprenticeship, in a power and concentration that the more easily satisfied painter does not attain.

- 1 2 3 "Work of Two American Realists; Recent Paintings by Katherine Schmidt and Gifford Beal Shown". New York Times. 1931-02-21. p. 6.

- ↑ Edward Alden Jewell (1931-02-18). "Art; Katherine Schmidt's Exhibition". New York Times. p. 14.

- ↑ Edward Alden Jewell (1932-11-27). "Native Art: A Lively Display at Whitney Museum on American surrealism show at Whitney". New York Times. p. X9.

- ↑ Edward Alden Jewell (1933-01-08). "Purchases at Whitney". New York Times. p. X12.

- ↑ "Detailed description of the Downtown Gallery records, 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- ↑ Edward Alden Jewell (1934-04-06). "Eve and Her Snake Adorn Art Exhibit; Katherine Schmidt's Painting of Serpents and Nudes Illustrated in Show". New York Times. p. 26.

- ↑ "Ruth Draper, 72, Monologist, Dies". New York Times. 1956-12-31. p. 13.

- ↑ "Ruth Draper". New York Times. 1934-12-27. p. 24.

- ↑ "In the Galleries—News and Comments; Katherine Schmidt At Downtown Galleries". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1934-04-15. p. 14 B-C.

- ↑ Edward Alden Jewell (1939-03-12). "Our Annual Non-Objective Field-Day". New York Times. p. 158.

- 1 2 "Art Doings of the Week". New York Sun. 1942-09-25. p. 25.

- 1 2 3 Max Doerner (1984). The Materials of the Artist and Their Use in Painting, with Notes on the Techniques of the Old Masters. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0-15-657716-8.

- 1 2 "Art: Something for Everyone in Prints: Graphic Society's Show at the A.A.A. Gallery". New York Times. 1965-03-06. p. 22.

- ↑ Hilton Kramer (1971-01-30). "In Giacometti's Graphic Art, Adventure". New York Times. p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Hamilton Easter Field (1921). "Comment on the Arts" (PDF). The Arts. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Hamilton Easter Field. 1 (4): 50.

- ↑ "Salons of America, Inc., Next; Offshoot of Independents Prepares for Spring Exhibition". The Sun. New York, N.Y. 1924-03-14. p. 9.

- ↑ "New Gallery". Brooklyn Standard Union. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1927-04-24. p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 James N. Rosenberg (1923). New Pictures and the New Gallery 1923. New York: Privately printed for The New Gallery.

- 1 2 "Karfiol Heads Painters". New York Post. 1935-04-04. p. 2.

- 1 2 "Editor of Art Magazine Supports Museum Rental". New York Post. 1936-01-18. p. 26.

- ↑ "The New Society Adopts a Progressive Program". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1930-04-27. p. A18.

- ↑ "Recent News of Woodstock". Kingston Daily Freeman. Kingston, N.Y. 1933-02-18.

- ↑ Katherine Schmidt et. al. (January 1936). "Comment and Criticism; On the Rental Issue". American Magazine of Art (PDF). 29 (1): 43–44. JSTOR 23938861.

- ↑ "Artists Spurn Bid to Carnegie Show; Eight Members of Society of Painters Demand Rent for Exhibiting Pictures". New York Times. 1936-03-09. p. 1.

- ↑ Robert C. Vitz (January 1976). "Struggle and Response: American Artists and the Great Depression". New York History (PDF). 57 (1): 97. JSTOR 23169707.

- ↑ "The Neighborhood Playhouse" (PDF). Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- ↑ "Catherine Schmidt in household of Charles Schmidt, Manhattan Ward 12, New York, New York, United States". "United States Census, 1910," database with images, FamilySearch; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 1431, sheet 16A, NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,375,040. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Charles Schmidt, Manhattan Assembly District 22, New York, New York, United States". "United States Census, 1920," database with images, FamilySearch; citing sheet 4B, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,821,226. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ↑ "History – The Residences at PS186". Alembic Community Development, Boys & Girls Club of Harlem, and Monadnock Development, LLC. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- ↑ "Katherine Kuniyoshi, 1926". "New York, New York Passenger and Crew Lists, 1909, 1925–1957," database with images, FamilySearch; citing Immigration, New York, New York, United States, NARA microfilm publication T715 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.). Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ↑ "Katherine Kuniyoshi". "New York, Southern District Index to Petitions for Naturalization, 1824–1941," database, FamilySearch; from "Alphabetical Index to Petitions for Naturalization of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, 1824–1941," database, Fold3.com; citing NARA microfilm publication M1676 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 80. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ↑ "Services Are Held, Woodstock, May 23, Funeral of Yashuo Kuniyoshi". Kingston Daily Freeman. Kingston, N.Y. 1953-05-26. p. 7.

- ↑ "Irvine Shubert, Jan 1986". "United States Social Security Death Index," database, FamilySearch; citing U.S. Social Security Administration, Death Master File, database (Alexandria, Virginia: National Technical Information Service, ongoing). Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- 1 2 "Irving Shuber in household of Max Shuber, Brooklyn Assembly District 18, Kings, New York, United States". "United States Census, 1920," database with images, FamilySearch; citing sheet 28B, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,821,172. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ↑ "Irvine J. Shubert, Obituary". New York Times. 1986-01-23. p. D26.

- ↑ Ann Lee Morgan Former Visiting Assistant Professor University of Illinois at Chicago (27 June 2007). The Oxford Dictionary of American Art and Artists. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-19-802955-7.