Karlskirche

| Karlskirche | |

|---|---|

|

Dome of Karlskirche in Vienna illuminated at night | |

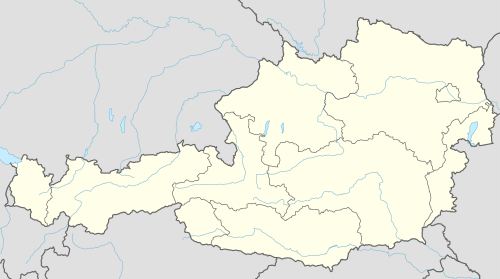

Shown within Austria | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Vienna, Austria |

| Geographic coordinates | 48°11′54″N 16°22′17″E / 48.198333°N 16.371389°ECoordinates: 48°11′54″N 16°22′17″E / 48.198333°N 16.371389°E |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Year consecrated | 1737 |

| Status | Active |

| Leadership | P. Milan Kucera, OCr |

| Website |

www |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, Joseph Emanuel Fischer von Erlach |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Architectural style | Baroque, Rococo |

| Groundbreaking | 1716 |

| Completed | 1737 |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | NNW |

| Length | 55 m (180.4 ft) |

| Width | 40 m (131.2 ft) |

| Dome(s) | 1 |

| Dome height (outer) | 70 m (229.7 ft) |

Karlskirche (St. Charles's Church) is a baroque church located on the south side of Karlsplatz in Vienna, Austria. Widely considered the most outstanding baroque church in Vienna, as well as one of the city's greatest buildings, Karlskirche is dedicated to Saint Charles Borromeo, one of the great counter-reformers of the sixteenth century.[1]

Located on the edge of the Innere Stadt, approximately 200 meters outside the Ringstraße, Karlskirche contains a dome in the form of an elongated ellipsoid. Since Karlsplatz was restored as an ensemble in the late 1980s, Karlskirche has garnered fame due to its dome and its two flanking columns of bas-reliefs, as well as its role as an architectural counterweight to the buildings of the Musikverein and of the Vienna University of Technology. The church is cared for by a religious order, the Knights of the Cross with the Red Star, and has long been the parish church as well as the seat of the Catholic student ministry of the Vienna University of Technology. Next to the Church was the Spitaler Gottesacker. Antonio Vivaldi was buried there.

Design and construction

In 1713, one year after the last great plague epidemic, Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, pledged to build a church for his namesake patron saint, Charles Borromeo, who was revered as a healer for plague sufferers. An architectural competition was announced, in which Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach prevailed over, among others, Ferdinando Galli-Bibiena and Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt. Construction began in 1716 under the supervision of Anton Erhard Martinelli. After J.B. Fischer's death in 1723, his son, Joseph Emanuel Fischer von Erlach, completed the construction in 1737 using partially altered plans. The church originally possessed a direct line of sight to the Hofburg and was also, until 1918, the imperial patron parish church.

As a creator of historic architecture, the elder Fischer von Erlach united the most diverse of elements. The façade in the center, which leads to the porch, corresponds to a Greek temple portico. The neighboring two columns, crafted by Lorenzo Mattielli, found a model in Trajan's Column in Rome. Next to those, two tower pavilions extend out and show the influence of the Roman baroque (Bernini and Borromini). Above the entrance, a dome rises up above a high drum, which the younger J.E. Fischer shortened and partly altered.

Iconography

The iconographical program of the church originated from the imperial official Carl Gustav Heraeus and connects St. Charles Borromeo with his imperial benefactor. The relief on the pediment above the entrance with the cardinal virtues and the figure of the patron on its apex point to the motivation of the donation. This sculpture group continues onto the attic story as well. The attic is also one of the elements which the younger Fischer introduced. The columns display scenes from the life of Charles Borromeo in a spiral relief and are intended to recall the two columns, Boaz and Jachim, that stood in front of the Temple at Jerusalem. They also recall the Pillars of Hercules and act as symbols of imperial power. The entrance is flanked by angels from the Old and New Testaments.

This program continues in the interior as well, above all in the dome fresco by Johann Michael Rottmayr of Salzburg and Gaetano Fanti, which displays an intercession of Charles Borromeo, supported by the Virgin Mary. Surrounding this scene are the cardinal virtues. The frescos in a number of side chapels are attributed to Daniel Gran.

The high altarpiece portraying the ascension of the saint was conceptualized by the elder Fischer and executed by Ferdinand Maxmilian Brokoff. The altar paintings in the side chapels are by various artists, including Daniel Gran, Sebastiano Ricci, Martino Altomonte and Jakob van Schuppen. A wooden statue of St. Anthony by Josef Josephu is also on display.

As strong effect emanates from the directing of light and architectural grouping, in particular the arch openings of the main axis. The color scheme is characterized by marble with sparring and conscious use of gold leaf. The large round glass window high above the main altar with the Hebrew Tetragrammaton/Yahweh symbolizes God's omnipotence and simultaneously, through its warm yellow tone, God's love. Below is a representation of Apotheosis of Saint Charles Borromeo.

Next to the structures at Schönbrunn Palace, which maintain this form but are more fragmented, the Karlskirche is Fischer's greatest work. It is also an expression of the Austrian joie de vivre stemming from the victorious end of the Turkish Wars.

Popular History

Hedwig Kiesler (age 19), later American movie actress and inventor Hedy Lamarr, married Friedrich Mandl (age 32), businessman and Austrofascist, in the tiny chapel of this elaborate church on 10 August 1933. With over 200 prominent guests attending, Kiesler wore “a black-and-white print dress” and carried “a bouquet of white orchids.”[2]

Gallery

Karlskirche

Karlskirche- Karlskirche

Karlskirche

Karlskirche Karlskirche

Karlskirche Karlskirche

Karlskirche- Karlskirche at night

Karlskirche at night

Karlskirche at night Karlskirche at night

Karlskirche at night Old Testament Angel

Old Testament Angel- Organ loft

Karlskirche at dusk

Karlskirche at dusk Saints Jerome and Augustine, High Altar, by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach

Saints Jerome and Augustine, High Altar, by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach Apotheosis of Saint Charles Borromeo by Alberto Camesina

Apotheosis of Saint Charles Borromeo by Alberto Camesina- Intercession of Charles Borromeo supported by the Virgin Mary by Rottmayr

Column with spiral narrative as on Trajan's Column

Column with spiral narrative as on Trajan's Column High Altar

High Altar The gold piece high above the altar symbolizing Yahweh

The gold piece high above the altar symbolizing Yahweh

References

- Citations

- Bibliography

- Brook, Stephan (2012). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Vienna. London: Dorling Kindersley Ltd. ISBN 978-0756684280.

- Charpentrat, Pierre (1967). Living Architecture: Baroque. Oldbourne. p. 91. OCLC 59920343.

- Clark, Roger (1985). Precedents in Architecture. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. pp. 165, 208. ISBN 0-442-21668-8.

- Gaillemin, Jean-Louis (1994). Knopf Guides: Vienna. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0679750680.

- Meth-Cohn, Delia (1993). Vienna: Art and History. Florence: Summerfield Press. ASIN B000NQLZ5K.

- Schnorr, Lina (2012). Imperial Vienna. Vienna: HB Medienvertrieb GesmbH. ISBN 978-3950239690.

- Schulte-Peevers, Andrea (2007). Alison Coupe, ed. Michelin Green Guide Austria. London: Michelin Travel & Lifestyle. ISBN 978-2067123250.

- Trachtenberg, Marvin; Hyman, Isabelle (1986). Architecture: From Prehistory to Post-Modernism. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. pp. 370–371. ISBN 0-13-044702-1.

- Unterreiner, Katrin; Gredler, Willfried (2009). The Hofburg. Vienna: Pichler Verlag. ISBN 978-3854314912.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Karlskirche, Vienna. |

- Karlskirche at Sacred Destinations

- Great Buildings