Kalmykia

| Republic of Kalmykia Республика Калмыкия (Russian) Хальмг Таңһч (Kalmyk) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| — Republic — | |||

| |||

|

| |||

| |||

|

| |||

| Political status | |||

| Country | Russia | ||

| Federal district | Southern[2] | ||

| Economic region | Volga[3] | ||

| Established | July 29, 1958[4] | ||

| Capital | Elista | ||

| Government (as of July 2014) | |||

| • Head[5] | Alexey Orlov[6] | ||

| • Legislature | People's Khural (Parliament)[7] | ||

| Statistics | |||

| Area (as of the 2002 Census)[8] | |||

| • Total | 76,100 km2 (29,400 sq mi) | ||

| Area rank | 41st | ||

| Population (2010 Census)[9] | |||

| • Total | 289,481 | ||

| • Rank | 78th | ||

| • Density[10] | 3.8/km2 (9.8/sq mi) | ||

| • Urban | 44.1% | ||

| • Rural | 55.9% | ||

| Population (January 2014 est.) | |||

| • Total | 282,021[11] | ||

| Time zone(s) | MSK (UTC+03:00)[12] | ||

| ISO 3166-2 | RU-KL | ||

| License plates | 08 | ||

| Official languages | Russian;[13] Kalmyk[14] | ||

| Official website | |||

The Republic of Kalmykia (Russian: Респу́блика Калмы́кия, tr. Respublika Kalmykiya; IPA: [rʲɪsˈpublʲɪkə kɐlˈmɨkʲɪjə]; Kalmyk: Хальмг Таңһч, Xaľmg Tañhç) is a province of Russia (a republic). As of the 2010 Census, its population was 289,481.[9]

It is the only region in Europe where Buddhism is practiced by a plurality of the population.[15] It has become well known as an international center for chess. Its former President, Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, is the head of the International Chess Federation (FIDE). The 33rd Chess Olympiad was held in Elista, the capital of Kalmykia.

Geography

stan

*Smaller areas along the north Caucasus are the republics: Karachay-Cherkessia, Kabardino-Balkaria, North Ossetia-Alania, Ingushetia, and Chechnya

*Yellow is the Southern Federal District and Pink is the North Caucasus Federal District

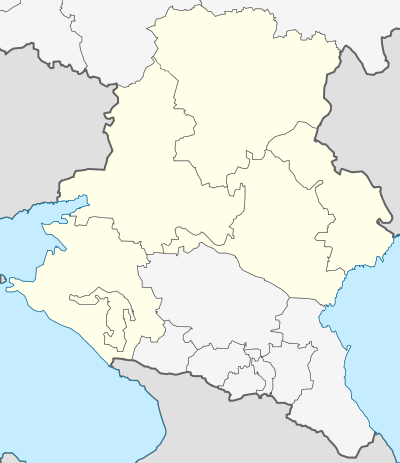

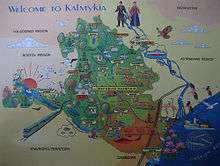

The republic is located in the southwestern part of European Russia and borders, clockwise, with Volgograd Oblast in the northwest and north, Astrakhan Oblast in the north and east, the Republic of Dagestan in the south, Stavropol Krai in the southwest, and with Rostov Oblast in the west. It is washed by the Caspian Sea in the southeast.

A small stretch of the Volga River flows through eastern Kalmykia. Other major rivers include the Yegorlyk, the Kuma, and the Manych. Lake Manych-Gudilo is the largest lake; other lakes of significance include Lakes Sarpa and Tsagan-Khak. In all, however, Kalmykia possesses few lakes.

Kalmykia's natural resources include coal, oil, and natural gas.

The republic's wildlife includes the saiga antelope, whose habitat is protected in Chyornye Zemli Nature Reserve.

Climate

Kalmykia has a continental climate, with very hot and dry summers and cold winters with little snow. The average January temperature is −5 °C (23 °F) and the average July temperature is +24 °C (75 °F). Average annual precipitation ranges from 170 millimeters (6.7 in) in the east of the republic to 400 millimeters (16 in) in the west.

History

According to the Kurgan hypothesis the upland regions of Kalmykia formed part of the cradle of Indo-European culture. Hundreds of Kurgans can be seen in these areas, known as the Indo-European Urheimat (Samara culture, Sredny Stog culture, Yamna culture).

The territory of Kalmykia is unique in that it has been the home in successive periods to many major world religions and ideologies. Prehistoric paganism and shamanism gave way to Judaism with the Khazars. This was succeeded by Islam with the Alans while the Mongol hordes brought Tengriism, and the later Nogais were Muslim, before their replacement by the present-day Buddhist Oirats/Kalmyks. With the annexation of the territory by the Russian Empire, Christianity arrived with Slavic settlers, while all religions were suppressed after the Russian Revolution, when Communism dominated. Shamanism has in all probability remained a constant, often hidden, substrate of folk-practice, as it is today.

Kalmyk autonomy

The ancestors of the Kalmyks, the Oirats, migrated from the steppes of southern Siberia on the banks of the Irtysh River to the Lower Volga region. Various reasons have been given for the move, but the generally accepted answer is that the Kalmyks sought abundant pastures for their herds. Another motivation may have been to escape the growing dominance of the neighboring Dzungar Mongol tribe.[16] They reached the lower Volga region in or about 1630. That land, however, was not uncontested pastures, but rather the homeland of the Nogai Horde, a confederation of Turkic-speaking nomadic tribes. The Kalmyks expelled the Nogais who fled to the Caucasian plains and to the Crimean Khanate, areas under the control of the Ottoman Empire. Some Nogai groups sought the protection of the Russian garrison at Astrakhan. The remaining nomadic Mongol Oirats tribes became vassals of Kalmyk Khan.

The Kalmyks settled in the wide open steppes from Saratov in the north to Astrakhan on the Volga delta in the south and to the Terek River in the southwest. They also encamped on both sides of the Volga River, from the Don River in the west to the Ural River in the east. Although these territories had been recently annexed by Russia, it was in no position to settle the area with Russian colonists. This area under Kalmyk control would eventually be called the Kalmyk Khanate.

Within twenty-five years of settling in the lower Volga region, the Kalmyks became subjects of the Tsar. In exchange for protecting Russia’s southern border, the Kalmyks were promised an annual allowance and access to the markets of Russian border settlements. The open access to Russian markets was supposed to discourage mutual raiding on the part of the Kalmyks and of the Russians and Bashkirs, a Russian-dominated Turkic people, but this was not often the practice. In addition, Kalmyk allegiance was often nominal, as the Kalmyk Khans practiced self-government, based on a set of laws they called the Great Code of the Nomads (Iki Tsaadzhin Bichig).

The Kalmyk Khanate reached its peak of military and political power under Ayuka Khan (1669–1724). During his era, the Kalmyk Khanate fulfilled its responsibility to protect the southern borders of Russia and conducted many military expeditions against its Turkic-speaking neighbors. Successful military expeditions were also conducted in the Caucasus. The Khanate experienced economic prosperity from free trade with Russian border towns, China, Tibet and with their Muslim neighbors. During this era, the Kalmyks also kept close contacts with their Oirat kinsmen in Dzungaria, as well as the Dalai Lama in Tibet.

Imposition of Russian rule

After the death of Ayuka Khan, the Tsarist government implemented policies that gradually chipped away at the autonomy of the Kalmyk Khanate. These policies, for instance, encouraged the establishment of Russian and German settlements on pastures the Kalmyks roamed in the lower Volga region. The settlers took over land used by Kalmyks to feed their livestock and, in some cases, forced Kalmyks into servitude. The Russian Orthodox church, by contrast, pressured many Kalmyks to adopt Orthodoxy. The Tsarist government imposed a council on the Kalmyk Khan, diluting his authority, while continuing to expect the Kalmyk Khan to provide cavalry units to fight on behalf of Russia. By the mid-18th century, Kalmyks were increasingly disillusioned with Russian encroachment and interference in its internal affairs.

Ubashi Khan, the great-grandson of Ayuka Khan and the last Kalmyk Khan, decided to return his people to their ancestral homeland, Dzungaria. Under his leadership, approximately 200,000 Kalmyks migrated directly across the Central Asian desert. Along the way, many Kalmyks were killed in ambushes or captured and enslaved by their Kazakh and Kyrgyz enemies. Many also died of starvation or thirst. After several grueling months of travel, only 96,000 Kalmyks reached the Manchu Empire's western outposts in Xinjiang near the Balkhash Lake.

After failing to stop the flight, Catherine the Great abolished the Kalmyk Khanate, transferring all governmental powers to the Governor of Astrakhan. The Kalmyks who remained in Russian territory continued to fight in Russian wars, e.g., the Napoleonic Wars (1812–1815), the Crimean War (1853–1856) and Ottoman wars. They gradually created fixed settlements with houses and temples, instead of their transportable round felt yurts. In 1865, Elista, the future capital of the Kalmykia, was built. This settlement process lasted until well after the Russian Revolution.

Civil War and the flight of the Don Kalmyks

After the October Revolution in 1917, many Don Kalmyks joined the White Russian army and fought under the command of Generals Denikin and Wrangel during the Russian Civil War. Before the Red Army broke through to the Crimean Peninsula towards the end of 1920, a large group of Kalmyks fled from Russia with the remnants of the defeated White Army to the Black Sea ports of Turkey.

The majority of the refugees chose to resettle in Belgrade, Serbia. Other, much smaller, groups chose Sofia (Bulgaria), Prague (Czechoslovakia) and Paris and Lyon (France). The Kalmyk refugees in Belgrade built a Buddhist temple there in 1929.

The years of Soviet rule

In the summer of 1919, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin issued an appeal[17] to the Kalmyk people, calling for them to revolt and to aid the Red Army. Lenin promised to provide the Kalmyks, among other things, a sufficient quantity of land for their own use. The promise came to fruition on November 4, 1920 when a resolution was passed by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee proclaiming the formation of the Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast. Fifteen years later, on October 22, 1935, the Oblast was elevated to republic status, Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

Contrary to the proclamations of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and of the Bolshevik propaganda slogan promising the "right of nations to self determination," the Oblast and its successor government were not autonomous governing bodies. Its nominal leaders, radical Communist intellectuals, failed to promote and protect the interests of the Kalmyk people, because real power was concentrated in the hands of the Soviet authorities in Moscow. According to Dorzha Arbakov, a Kalmyk school teacher turned anti-Soviet partisan fighter, these governing bodies were a tool the Bolsheviks used to control the Kalmyk people:

... the Soviet authorities were greatly interested in Sovietizing Kalmykia as quickly as possible and with the least amount of bloodshed. Although the Kalmyks alone were not a significant force, the Soviet authorities wished to win popularity in the Asian and Buddhist worlds by demonstrating their evident concern for the Buddhists in Russia.[18]

In spite of the efforts of Soviet authorities to gain popular support, the Kalmyk people remained staunchly loyal, first and foremost to their traditional leaders, the nobility and the clergy, as they always had been. To the Soviet authorities, Kalmykia's leaders were sources of anti-Communism and Kalmyk nationalism. Later on, the authorities would persecute Kalmyk leaders through executions, deportations to labor camps in Siberia and the confiscation of property.

After establishing control, the Soviet authorities did not overtly enforce an anti-religion policy, other than through passive means, because it sought to bring Mongolia[19] and Tibet[20] into its sphere of influence. The government also was compelled to respond to domestic disturbances resulting from the economic policies of War Communism and the famine its policies induced in 1921.

The passive measures taken by Soviet authorities to control the people included the imposition of a harsh church tax to close churches, monasteries and parish schools. Public education became mandatory to indoctrinate the youth. The Cyrillic script replaced Todo Bichig, the traditional Kalmyk vertical script. In spite of these measures, some of the better known Kalmyk monasteries were able to expand their religious and educational work.

The Kalmyks of the Don Host, however, were not so fortunate. They were subject to the policies of de-cossackization where villages were destroyed, khuruls (temples) and monasteries were burned down and executions were indiscriminate. At the same time, grain, livestock and other food stuffs were seized. By 1925 the Don Host did not have any khuruls, monasteries or practicing clergy.

In December 1927 the Fifteenth Party Congress of the Soviet Union passed a resolution calling for the "voluntary" collectivization of agriculture, but a shortage of grain in the following year was used as a pretext by the Soviet authorities to use force. The change in policy was accompanied by a new campaign of systematic and merciless repression, directed initially against the small farming class. The objective of this campaign was to suppress the resistance of the farming peasants to full-scale collectivization of agriculture.

In 1931, Joseph Stalin ordered the collectivization, closed the Buddhist monasteries, and burned the Kalmyks' religious texts. He deported all monks and all herdsmen owning more than 500 sheep to Siberia. The forced collectivization (as well as the dry, treeless landscape) was unsuited to the Kalmyk temperament and was a social, economic, and cultural disaster. About 60,000 Kalmyks died during the great famine of 1932 to 1933.

World War II

On June 22, 1941 the German army invaded the Soviet Union. By August 12, 1942 the German Army Group South captured Elista, the capital of the Kalmyk ASSR. After capturing the Kalmyk territory, German army officials established a propaganda campaign with the assistance of anti-communist Kalmyk nationalists, including white emigre, Kalmyk exiles. German benevolence, however, did not extend to all people living in the Kalmyk ASSR. At least 93 Jewish families, for example, were rounded up and killed. The total Jewish dead numbered between 100[21] and upwards of 700, according to documents held in the Kalmyk State Archives.[22] The campaign was focused primarily on recruiting and organizing Kalmyk men into anti-Soviet, militia units.

- Kalmüken Verband Dr. Doll (Kalmukian Volunteers)

- Abwehrtrupp 103 (Kalmukian Volunteers)

- Kalmücken-Legion or Kalmücken-Kavallerie-Korps (Kalmukian Volunteers)

The Kalmyk units were extremely successful in flushing out and killing Soviet partisans. But by December 1942, the Soviet Red army retook the Kalmyk ASSR, forcing the Kalmyks assigned to those units to flee, in some cases, with their wives and children in hand.

The Kalmyk units retreated westward into unfamiliar territory with the retreating German army and were reorganized into the Kalmuck Legion, although the Kalmyks themselves preferred the name Kalmuck Cavalry Corps. The casualty rate also increased substantially during the retreat, especially among the Kalmyk officers. To replace those killed, the German army imposed forced conscription, taking in teenagers and middle-aged men. As a result, the overall effectiveness of the Kalmyk units declined.

By the end of the war, the remnants of the Kalmuck Cavalry Corps made its way to Austria where the Kalmyk soldiers and their family members became post-war refugees.

Those who did not want to leave formed militia units that chose to stay behind and harass the oncoming Soviet Red Army.

Although a large number of Kalmyks chose to fight against the Soviet Union, the majority by-and-large remained loyal to their country, fighting the German army in regular Soviet Red army units and in partisan resistance units behind the battlelines throughout the Soviet Union. Before their removal from the Soviet Red Army and from partisan resistance units after December 1943, approximately 8,000 Kalmyks were awarded various orders and medals, including 21 Kalmyk men who were recognized as a Hero of the Soviet Union.[23]

Kalmyk deportation of 1943

On December 27, 1943, Soviet authorities declared the Kalmyk people guilty of cooperation with the German Army and ordered the deportation of the entire Kalmyk population, including those who had served with the Soviet Army, to various locations in Central Asia and Siberia. In conjunction with the deportation, the Kalmyk ASSR was abolished and its territory was split between adjacent Astrakhan, Rostov and Stalingrad Oblasts and Stavropol Krai. To completely obliterate any traces of the Kalmyk people, the Soviet authorities renamed the former republic's towns and villages.[24]

The population transfer occurred immediately in the middle of the evening. No one was given advanced notification or time to assemble their belongings, including warm clothing, in preparation for their forced relocation. They were transported in trucks from their homes to the local railway stations where they were loaded in unheated cattle cars. In many cases, the cars were filled beyond capacity and did not contain bathrooms. Food was not provided, and water fell through the holes and cracks in the cattle car in the form of snow. As a result of these harsh conditions, many children and elderly men and women died en route.

Post-war Kalmykia

Due to their widespread dispersal in Siberia their language and culture suffered possibly irreversible decline. Khrushchev finally allowed their return in 1957, when they found their homes, jobs and land occupied by imported Russians and Ukrainians, who remained. On January 9, 1957, Kalmykia again became an autonomous oblast, and on July 29, 1958, an autonomous republic within the Russian SFSR.

In the following years bad planning of agricultural and irrigation projects resulted in widespread desertification, and economically unviable industrial plants were constructed.

After dissolution of the USSR, Kalmykia kept the status of an autonomous republic within the newly formed Russian Federation (effective March 31, 1992).

Administrative divisions

Demographics

Population: 289,481 (2010 Census);[9] 292,410 (2002 Census);[25] 322,589 (1989 Census).[26]

Vital statistics

| Average population (x 1000) | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | Fertility rates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 269 | 4,801 | 1,661 | 3,140 | 17.8 | 6.2 | 11.7 | |

| 1975 | 283 | 5,923 | 2,228 | 3,695 | 20.9 | 7.9 | 13.1 | |

| 1980 | 299 | 7,062 | 2,735 | 4,327 | 23.6 | 9.1 | 14.5 | |

| 1985 | 314 | 7,945 | 2,832 | 5,113 | 25.3 | 9.0 | 16.3 | |

| 1990 | 326 | 6,828 | 2,669 | 4,159 | 20.9 | 8.2 | 12.7 | 2,66 |

| 1991 | 327 | 6,369 | 2,755 | 3,614 | 19.5 | 8.4 | 11.1 | 2,58 |

| 1992 | 323 | 5,865 | 2,806 | 3,059 | 18.2 | 8.7 | 9.5 | 2,57 |

| 1993 | 319 | 5,027 | 3,167 | 1,860 | 15.8 | 9.9 | 5.8 | 2,30 |

| 1994 | 317 | 4,684 | 3,226 | 1,458 | 14.8 | 10.2 | 4.6 | 2,20 |

| 1995 | 316 | 4,321 | 3,359 | 962 | 13.7 | 10.6 | 3.0 | 2,03 |

| 1996 | 314 | 3,929 | 3,232 | 697 | 12.5 | 10.3 | 2.2 | 1,82 |

| 1997 | 313 | 3,845 | 3,072 | 773 | 12.3 | 9.8 | 2.5 | 1,77 |

| 1998 | 311 | 3,858 | 3,279 | 579 | 12.4 | 10.5 | 1.9 | 1,76 |

| 1999 | 309 | 3,598 | 3,356 | 242 | 11.6 | 10.8 | 0.8 | 1,62 |

| 2000 | 308 | 3,473 | 3,439 | 34 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 0.1 | 1,55 |

| 2001 | 302 | 3,530 | 3,357 | 173 | 11.7 | 11.1 | 0.6 | 1,57 |

| 2002 | 295 | 3,729 | 3,637 | 92 | 12.7 | 12.3 | 0.3 | 1,70 |

| 2003 | 291 | 3,874 | 3,437 | 437 | 13.3 | 11.8 | 1.5 | 1,77 |

| 2004 | 291 | 3,923 | 3,184 | 739 | 13.5 | 11.0 | 2.5 | 1,77 |

| 2005 | 290 | 3,788 | 3,350 | 438 | 13.1 | 11.5 | 1.5 | 1,69 |

| 2006 | 289 | 3,820 | 3,207 | 613 | 13.2 | 11.1 | 2.1 | 1,69 |

| 2007 | 289 | 4,146 | 3,141 | 1,005 | 14.3 | 10.9 | 3.5 | 1,83 |

| 2008 | 289 | 4,354 | 2,976 | 1,378 | 15.1 | 10.3 | 4.8 | 1,93 |

| 2009 | 289 | 4,270 | 3,115 | 1,155 | 14.8 | 10.8 | 4.0 | 1,81 |

| 2010 | 289 | 4,432 | 3,191 | 1,241 | 15.3 | 11.0 | 4.3 | 1,88 |

| 2011 | 288 | 4,194 | 2,920 | 1,274 | 14,5 | 10,1 | 4.4 | 1,81 |

| 2012 | 286 | 4,268 | 2,870 | 1,398 | 15,0 | 10,1 | 4.9 | 1,89 |

| 2013 | 283 | 4,126 | 2,805 | 1,321 | 14,6 | 9,9 | 4.7 | 1,88 |

| 2014 | 281 | 3,969 | 2,787 | 1,182 | 14,1 | 9,9 | 4.2 | 1,85 |

| 2015 | 280 | 3,823 | 2,743 | 1,080 | 13,6 | 9,8 | 3.8 | 1,82(e) |

Ethnic groups

According to the 2010 Census, Kalmyks make up 57.4% of the republic's population. Other groups include Russians (30.2%), Dargins (2.7%), Chechens (1.2%), Kazakhs (1.7%), Turks (1.3%), Avars (0.8%) Ukrainians (0.5%), ethnic Germans (0.4%).[9]

| Ethnic group |

1926 census | 1939 census | 1959 census | 1970 census | 1979 census | 1989 census | 2002 census | 2010 census1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Kalmyks | 107,026 | 75.6% | 107,315 | 48.6% | 64,882 | 35.1% | 110,264 | 41.1% | 122,167 | 41.5% | 146,316 | 45.4% | 155,938 | 53.3% | 162,740 | 57.4% |

| Russians | 15,212 | 10.7% | 100,814 | 45.7% | 103,349 | 55.9% | 122,757 | 45.8% | 125,510 | 42.6% | 121,531 | 37.7% | 98,115 | 33.6% | 85,712 | 30.2% |

| Others | 19,356 | 13.7% | 12,555 | 5.7% | 16,626 | 9.0% | 34,972 | 13.0% | 46,850 | 15.9% | 54,732 | 17.0% | 38,357 | 13.1% | 35,239 | 12.4% |

| 1 5,790 people were registered from administrative databases, and could not declare an ethnicity. It is estimated that the proportion of ethnicities in this group is the same as that of the declared group.[27] | ||||||||||||||||

This statistics is about the demographics of the Kalmyks in the Russian Empire, Soviet Union and Russian Federation.

| 1897[28] | 1926 | 1939 | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | 2002 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 190,648 | 128,809 | 129,786 | 100,603 | 131,318 | 140,103 | 165,103 | 174,000 | 183,372 |

Religion

Tibetan Buddhism is the traditional and most popular religion amongst the Kalmyks, while Russians in the country practise predominantly Russian Orthodoxy. A minority of Kalmyks practises pre-Buddhist shamanism or Tengrism (a contemporary revival of the Turkic and Mongolic shamanic religions). Many people are unaffiliated and non-religious.

As of a 2012 official survey[29] 37.6% of the population of Kalmykia adheres to Buddhism, 18% to the Russian Orthodox Church, 4% to Islam, 3% to Tengrism or Kalmyk shamanism, 1% declares to be generically unaffiliated Christian, 1% are either Orthodox Christian believers who don't belong to church or members of non-Russian Orthodox churches, 0.4% adheres to forms of Hinduism, and 9.0% follows other religion or did not give an answer to the survey. In addition, 13% of the population declares to be "spiritual but not religious" and another 13% to be atheist.[29]

Politics

The head of the government in Kalmykia is called "The Head of the Republic". The President of Russia selects a candidate for the Head of the Republic position and presents it to the Parliament of Kalmyk Republic, the People's Khural, for approval. If a candidate is not approved, the President of the Russian Federation can dissolve the Parliament and set up new elections.

From 1993 to 2010, the Head of the Republic was Kirsan Nikolayevich Ilyumzhinov. He is also the president of the world chess organization FIDE. He has spent much of his fortune on promoting chess in Kalmykia—where chess is compulsory in all primary schools—and also overseas, with Elista, the capital of Kalmykia, hosting many international tournaments.

In the late 1990s, the Ilyumzhinov government was alleged to be spending too much government money on chess-related projects. The allegations were published in Sovietskaya Kalmykia, the opposition newspaper in Elista. Larisa Yudina, the journalist who investigated these accusations, was kidnapped and murdered in 1998. Two men, Sergei Vaskin and Tyurbi Boskomdzhiv, who worked in the local civil service, were charged with her murder, one of them having been a former presidential bodyguard. After prolonged investigations by the Russian authorities, both men were found guilty and jailed, but no evidence was discovered that Ilyumzhinov himself was in any way responsible.[31][32][33]

On October 24, 2010, Ilyumzhinov was replaced by Alexey Orlov as the new Head of Kalmykia. Since 2008, Anatoly Kozachko has been President of the Parliament, the People's Khural. The current Prime Minister of Kalmykia is Lyudmila Ivanovna. All the three top politicians belong to the Kremlin's "United Russia" Party.[34]

Economy

Kalmykia has a developed agricultural sector. Other developed industries include the food processing and oil and gas industries.

As most of Kalmykia is arid, irrigation is necessary for agriculture. The Chernye Zemli Irrigation Scheme (Черноземельская оросительная система) in southern Kalmykia receives water from the Caucasian rivers Terek and Kuma via a chain of canals: water flows from the Terek to the Kuma via the Terek-Kuma Canal, then to the Chogray Reservoir on the East Manych River via the Kuma-Manych Canal, and finally into Kalmykia's steppes over the Chernye Zemli Main Canal, constructed in the 1970s.[35]

Annual budget: revenues and expenditures: about $100 million. Annual oil production: about 200,000 metric tonnes.

Education

Kalmyk State University is the largest higher education facility in the republic.

Emigration and culture

The Kalmyks of Kyrgyzstan live primarily in the Karakol region of eastern Kyrgyzstan. They are referred to as Sart Kalmyks. The origin of this name is unknown. Likewise, it is not known when, why and from where this small group of Kalmyks migrated to eastern Kyrgyzstan. Due to their minority status, the Sart Kalmyks have adopted the Kyrgyz language and culture of the majority Kyrgyz population. As a result, nearly all now are Muslims.

Although Sart Kalmyks are Muslims, Kalmyks elsewhere by and large remain faithful to the Gelugpa Order of Tibetan Buddhism. In Kalmykia, for example, the Gelugpa Order with the assistance of the government has constructed numerous Buddhist temples. In addition, the Kalmyk people recognize Tenzin Gyatso, 14th Dalai Lama as their spiritual leader and Erdne Ombadykow, a Kalmyk American, as the supreme lama of the Kalmyk people. The Dalai Lama has visited Elista on a number of occasions.

The Kalmyks have also established communities in the United States, primarily in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The majority are descended from those Kalmyks who fled from Russia in late 1920 to France, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and, later, Germany. Many of those Kalmyks living in Germany at the end of World War II were eventually granted passage to the United States.

As a consequence of their decades-long migration through Europe, many older Kalmyks are fluent in German, French and Serbo-Croatian, in addition to Russian and their native Kalmyk language. There are several Kalmyk Buddhist temples in Monmouth County, New Jersey, where the vast majority of American Kalmyks reside, as well as a Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center and monastery in Washington Township, New Jersey. At one point during the 20th century, there was a Kalmyk Buddhist temple in Belgrade, Serbia.

The word Kalmyk means 'those who remained'. Its origin is unknown but this name was known centuries before a large part of the Kalmyks moved back from the Volga River to Dzhungaria in the 18th century.

There are three cultural subgroups within the Kalmyk nation: Turguts, Durbets (Durwets), and Buzavs (Oirats, who joined the Russian Cossacks), as well as some villages of Hoshouts and Zungars. The Durbets subgroup includes the Chonos tribe (literally meaning "a tribe of the wolf", also called "Shonos", "Chinos", "A-Shino", or "A-Chino"), which is considered to be one of the most ancient tribes in the world, dating back to the 6th to 11th century.

Kalmykia staged the 2006 World Chess Championship between Veselin Topalov and Vladimir Kramnik.[36]

Most of the Republic of Kalmykia lies in the Caspian Depression, a low-lying region up to 27 meters (89 ft) below sea level.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Law #44-I-Z

- ↑ Президент Российской Федерации. Указ №849 от 13 мая 2000 г. «О полномочном представителе Президента Российской Федерации в федеральном округе». Вступил в силу 13 мая 2000 г. Опубликован: "Собрание законодательства РФ", №20, ст. 2112, 15 мая 2000 г. (President of the Russian Federation. Decree #849 of May 13, 2000 On the Plenipotentiary Representative of the President of the Russian Federation in a Federal District. Effective as of May 13, 2000.).

- ↑ Госстандарт Российской Федерации. №ОК 024-95 27 декабря 1995 г. «Общероссийский классификатор экономических регионов. 2. Экономические районы», в ред. Изменения №5/2001 ОКЭР. (Gosstandart of the Russian Federation. #OK 024-95 December 27, 1995 Russian Classification of Economic Regions. 2. Economic Regions, as amended by the Amendment #5/2001 OKER. ).

- ↑ Decree of July 29, 1958

- ↑ Steppe Code (Constitution) of the Republic of Kalmykia, Article 25

- ↑ Official website of the Head of the Republic of Kalmykia. Alexey Maratovich Orlov (Russian)

- ↑ Steppe Code (Constitution) of the Republic of Kalmykia, Article 33

- ↑ Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service) (2004-05-21). "Территория, число районов, населённых пунктов и сельских администраций по субъектам Российской Федерации (Territory, Number of Districts, Inhabited Localities, and Rural Administration by Federal Subjects of the Russian Federation)". Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года (All-Russia Population Census of 2002) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- 1 2 3 4 Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года (2010 All-Russia Population Census) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ↑ The density value was calculated by dividing the population reported by the 2010 Census by the area shown in the "Area" field. Please note that this value may not be accurate as the area specified in the infobox is not necessarily reported for the same year as the population.

- ↑ Republic of Kalmykia Territorial Branch of the Federal State Statistics Service. Численность постоянного населения Республики Калмыкия по городам и районам на 01.01.2014 года (Russian)

- ↑ Правительство Российской Федерации. Федеральный закон №107-ФЗ от 3 июня 2011 г. «Об исчислении времени», в ред. Федерального закона №271-ФЗ от 03 июля 2016 г. «О внесении изменений в Федеральный закон "Об исчислении времени"». Вступил в силу по истечении шестидесяти дней после дня официального опубликования (6 августа 2011 г.). Опубликован: "Российская газета", №120, 6 июня 2011 г. (Government of the Russian Federation. Federal Law #107-FZ of June 31, 2011 On Calculating Time, as amended by the Federal Law #271-FZ of July 03, 2016 On Amending Federal Law "On Calculating Time". Effective as of after sixty days following the day of the official publication.).

- ↑ Official on the whole territory of Russia according to Article 68.1 of the Constitution of Russia.

- ↑ Steppe Code (Constitution) of the Republic of Kalmykia, Article 17: Государственными языками в Республике Калмыкия являются калмыцкий и русский языки. [The official languages of the Republic of Kalmykia are the Kalmyk and Russian languages.]

- ↑ Brendan, Koerner. "How Buddhism Got to Russia". The Slate Group. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ↑ Robert L. Worden and Andrea Matles Savada. "Caught Between the Russians and the Manchus". Mongolia a Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ↑ Isvestia, Moscow, July 24, 1919

- ↑ Dorzha Arbakov, 'The Kalmyks' in Nikolai Dekker and Andrei Lebed, (Eds) Genocide in the USSR, Chapter II, Complete Destruction of National Groups as Groups, Series I, No. 40, (Institute for the Study of the USSR, 1958), p. 90.

- ↑ Bawden, C.R. The Modern History of Mongolia, Frederick A. Praeger, Publishers, New York, (1968).

- ↑ Meyer, Karl E. and Brysac, Shareen Blair. Tournament of Shadows, Counterpoint, Washington, DC, (1999)

- ↑

- ↑ "USHMM Receives Lost Archives from Kalmyk Republic of the Russian Federation Detailing Previously Unknown Atrocities". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. December 22, 2000. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ↑ Republic of Kalmykia | History

- ↑ Polian, P.M.; Pobol', N.L., eds. (2005). Stalinskie deportatsii 1928–1953. Rossiia. XX vek. Dokumenty (in Russian). Moscow: Mezhdunarodnyi fond "Demokratiia"; Maternik. pp. 410–34. ISBN 5-85646-143-6. OCLC 65289542.

- ↑ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian). Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ↑ Demoscope Weekly (1989). "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ↑ Перепись-2010: русских становится больше. Perepis-2010.ru (2011-12-19). Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- ↑ Demoscope.ru

- 1 2 3 Arena – Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia. Sreda.org

- ↑ 2012 Survey Maps. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27/08/2012. Retrieved 24-09-2012.

- ↑ World Press Freedom Review

- ↑ In Russia, many conform, few resist

- ↑ Kalder. Lost Cosmonaut, p70.

- ↑ http://gov.kalmregion.ru/ – See the web site of the Government of Kalmykia with links.

- ↑ "What Kalmykia's economy is based on" (Russian)

- ↑ Rohrer, Finlo (2006) "Game of kings takes centre stage"

Sources

- Конституционное Собрание Республики Калмыкия. 5 апреля 1994 г. «Степное Уложение (Конституция) Республики Калмыкия», в ред. Закона №358-IV-З от 29 июня 2012 г. «О внесении изменений в отдельные законодательные акты Республики Калмыкия по вопросам проведения выборов Главы Республики Калмыкия». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования в газетах "Хальмг Унн" и "Известия Калмыкии". Опубликован: "Известия Калмыкии", №60, 7 апреля 1994 г. (Constitutional Assembly of the Republic of Kalmykia. April 5, 1994 Steppe Code (Constitution) of the Republic of Kalmykia, as amended by the Law #358-IV-Z of June 29, 2012 On Amending Various Legislative Acts of the Republic of Kalmykia on the Issues of Organization of the Elections of the Head of the Republic of Kalmykia. Effective as of the day of the official publications in the Khalmg Unn" and "Izvestiya Kalmykii" newspapers.).

- Народный Хурал (Парламент) Республики Калмыкия. Закон №44-I-З от 14 июня 1996 г. «О государственных символах Республики Калмыкия», в ред. Закона №152-IV-З от 18 ноября 2009 г. «О внесении изменения в Закон Республики Калмыкия "О государственных символах Республики Калмыкия"». Вступил в силу с момента опубликования. Опубликован: "Ведомости Народного Хурала (Парламента) Республики Калмыкия",

№2, стр. 113, 1997 г. (People's Khural (Parliament) of the Republic of Kalmykia. Law #44-I-Z of June 14, 1996 On the Symbols of State of the Republic of Kalmykia, as amended by the Law #152-IV-Z of November 18, 2009 On Amending the Law of the Republic of Kalmykia "On the Symbols of State of the Republic of Kalmykia". Effective as of the moment of publication.).

- Президиум Верховного Совета СССР. Указ от 29 июля 1958 г. «О преобразовании Калмыцкой автономной области в Калмыцкую Автономную Советскую Социалистическую Республику». (Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. Decree of July 29, 1958 On the Transformation of Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast into the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. ).

Further reading

- Arbakov, Dorzha. Genocide in the USSR, Chapter II, Complete Destruction of National Groups as Groups, The Kalmyks, Nikolai Dekker and Andrei Lebed, Editors, Series I, No. 40, Institute for the Study of the USSR, Munich, 1958.

- Balinov, Shamba. Genocide in the USSR, Chapter V, Attempted Destruction of Other Religious Groups, The Kalmyk Buddhists, Nikolai Dekker and Andrei Lebed, Editors, Series I, No. 40, Institute for the Study of the USSR, Munich, 1958.

- Bethell, Nicholas. The Last Secret, Futura Publications Limited, Great Britain, 1974.

- Corfield, Justin. The History of Kalmykia: from Ancient times to Kirsan Ilyumzhinov and Aleksey Orlov, Australia, 2015. [The first major history of Kalmykia in English, heavily illustrated, and drawing on interviews with Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, Nicholas Ilyumzhinov and Aleksey Orlov amongst others.]

- Epstein, Julius. Operation Keelhaul, Devin-Adair, Connecticut, 1973.

- Grousset, René. The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia, Rutgers University Press, 1970.

- Halkovic, Jr., Stephen A. The Mongols of the West, Indiana University Uralic and Altaic Series, Volume 148, Larry Moses, Editor, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, Indiana University, Bloomington, 1985.

- Joachim Hoffmann: Deutsche und Kalmyken 1942 bis 1945, Rombach Verlag, Friedberg, 1986.

- Kalder, Daniel. Lost Cosmonaut: Observations of an Anti-tourist

- Muñoz, Antonio J. The East Came West: Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist Volunteers in the German Armed Forces, 1941–1945, Chapter 8, Followers of "The Greater Way": Kalmück Volunteers in the German Army, Antonio J. Muñoz, Editor, Axis Europa Books, Bayside, NY, 2001.

- Tolstoy, Nikolai. The Secret Betrayal, 1944–1947, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1977.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kalmykia. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kalmykia. |

- Official website of the Republic of Kalmykia (Russian)

- News from Kalmykia (English)

- Official website of the Kalmyk diplomatic representation at the President of the Russian Federation (English)(Russian)

- News about life in Kalmykia (Russian)

- Official website of the Kalmyk State University (Russian)

- News Agency of the Republic of Kalmykia (English)(Russian)

- Ethnologue report on Kalmyk language

- Forum of Kalmyk Internet Community

- Kalmyk Portal

- Web-Portal of the Interregional Not-for-Profit Organization "The Leaders of Kalmykia"

- Mistaken Foreign Myths about Shambhala

- The man who bought chess, The Observer 29 October 2006

- The Buddhist hordes of Kalmykia, The Guardian September 19, 2006

- Kalmyk Buddhist Temple in Belgrade (1929–1944)

- Earth to Kalmykia, Come In Please The Economist December 18, 1997

- Czech republics, New Humanist November–December, 2007

- Lagansky Express free bulletin board of the city Lagan

- Caspian fish Сity Lagan

- The nature of Kalmykia Video

- Photographs of Buddhist sites in Kalmykia and in Central Asia

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| |

|

Caspian Sea Mangystau Region, |