OR-7

OR-7 in Jackson County, Oregon, in May 2014 | |

| Other name(s) | Journey |

|---|---|

| Species | Canis lupus |

| Breed | Canis lupus occidentalis |

| Sex | Male |

| Born |

April 2009 Oregon |

| Nation from | United States |

| Parents | B-300 (mother)[1] |

| Offspring | 7 pups[2] |

| Weight | 90 pounds (41 kg) in February 2011[3] |

| Appearance | Gray |

| Named after | 7th wolf collared in Oregon |

| http://or7expedition.org/ | |

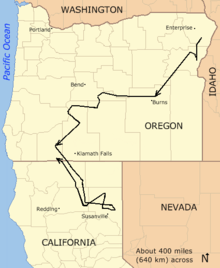

OR-7, also known as Journey, is a male gray wolf that was electronically tracked in Oregon and California in the United States. He was the first confirmed wolf in western Oregon since 1947, and the first in California since 1924. After the wolf left his pack in northeastern Oregon in September 2011, he wandered more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) through Oregon and Northern California.

By 2014, OR-7 had returned to the Rogue River watershed in the southern Cascade Range east of Medford, Oregon, with a mate. It is not known when the two wolves met but DNA tests of fecal samples show that she is related to wolves in two of the eight packs in northeastern Oregon. In early 2015, officials designated the two adult wolves and their offspring the Rogue Pack, the first wolf pack in western Oregon and the state's ninth overall since contemporary wolves entered Oregon from Idaho in the 1990s. The batteries in OR-7's tracking collar expired in October 2015, after which tracking of the pack depended on trail cameras and live sightings.

Background

Wolves were reintroduced into the Northern Rocky Mountains in the 1990s.[4] In February 2011, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife attached radio collars to several wolves in the Imnaha Pack in northeastern Oregon to allow study of their migration.[5] The pack was Oregon's first wolf pack since wolves were reintroduced in the state.[6] The wolves were numbered; one of them, a year-old male, was given the code OR-7 as the seventh wolf to be collared.[5][7][8]

Migration

As is common for non-dominant wolf males, OR-7 left the Imnaha Pack in the Wallowa Mountains near Joseph on September 10, 2011, presumably in search of a mate.[8][9] On November 1, he became the first wolf detected in Western Oregon in more than 60 years. Throughout November and most of December, OR-7 stayed within an area of 100 square miles (260 km2) south of Crater Lake National Park.[10] On November 14 the wolf was photographed east of Butte Falls, Oregon, by an automatic trail camera placed by a hunter hoping to track deer. OR-7 reached the southern Cascade Range in December, marking the first wolf appearance in southwestern Oregon since 1946.[4]

The wolf crossed the border into Northern California on December 28, becoming the first and only documented wolf in the state since 1924.[11][12] OR-7 remained in California, trekking through Siskiyou, Shasta and Lassen counties, until March. Tracks were found in Lassen County, but OR-7 was not seen in California. The wolf re-entered Shasta County on February 7, then moved into Siskiyou County approximately one week later. For 12 days OR-7 remained within roughly 10 miles (16 km) of the Oregon–California border before returning to Oregon's Klamath County on March 1.[9] OR-7 quickly made his way to Jackson County. By then the wolf had traveled more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km). (The Los Angeles Times reported more than 2,000 miles.)[12][13]

OR-7 returned to California, spending the summer of 2012 in the Plumas National Forest south of Mount Lassen and as of December 2012 had migrated to near Lake Almanor. The batteries in the wolf's GPS collar, by which he is tracked, were thought likely to expire by February 2014.[14] However, the tracking unit was still emitting signals in early June 2014.[15] The batteries lasted until October 2015.[16]

Pack formation

In May 2014, remote cameras in the Rogue River – Siskiyou National Forest captured photographs of OR-7 along with a female wolf who might have mated with him. In June 2014, US Fish and Wildlife and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists returned to the Cascade Mountains of southwest Oregon and photographed two pups. They took fecal samples for DNA testing in order to make decisive confirmation of the relation of the pups to OR-7.[17][18][19] By September, genetic tests run at the University of Idaho on the fecal samples confirmed that OR-7's mate is a wolf and that the two pups are their offspring. The tests also showed that the mate is related to the wolves in the Minam and Snake River packs of northeastern Oregon.[20]

The birth of wolf pups so close to the California border makes it likely that further dispersals will re-introduce a long-term wolf population to that state. It is possible that at about age 2, one or more of the pups may disperse south along the scent trail left by their father everywhere he went. On June 3, the California Fish and Game Commission voted 3–1 to protect those wolves, if any, under the state Endangered Species Act.[15]

In late 2014, the adult wolves and their pups were living in the southern Cascades east of Medford, in the Rogue River watershed. In early 2015, Oregon and Federal officials designated the group as the Rogue Pack, the ninth wolf pack in Oregon and first west of the Cascades.[21] By July 2015, wildlife officials reported evidence (small piles of scat) that OR-7 and his mate had produced a second litter of pups.[22] This was confirmed in August 2015, when trail cameras identified two new pups, bringing the known total of wolves in this pack to seven.[23]

Officials, who originally had no plans to replace OR-7's tracking collar when its three-year batteries went dead, decided to replace the collar in order to keep track of the pack,[15] which is protected under Oregon law and the Federal Endangered Species Act.[24] (Wolves were removed from the Oregon Endangered Species List in November 2015, but the OR–7 pack and other wolves in western Oregon remained on the Federal list.)[25] However, after three attempts to trap OR-7 or other members of the pack failed, the batteries died in October 2015. After that tracking of OR-7 depended on trail cameras and live sightings.[16] On February 26, 2016, a trail camera in the Rogue River – Siskiyou National Forest captured the image of OR-7 and one of his offspring.[26]

A few days after the OR-7 family became a designated pack, wildlife officials announced a "new area of known wolf activity" south of Klamath Falls. A wildlife camera near Keno confirmed the presence of an adult gray wolf unrelated to the Rogue Pack. This and any other wolves that migrate to western Oregon may offer genetic diversity to offspring of the Rogue Pack that disperse as adults to search for mates.[20][27] By July 2015, the Keno activity was being referred to as the "Keno Pair".[22]

The northeastern packs, as shown on an Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife map of wolf activity in January 2015, were the Snake River, Wallowa, Minam, Walla Walla, Wenaha, Mt. Emily, Umatilla River, and Meacham.[28][29] Not counting OR-7's new pups, there were 77 known wolves in Oregon in July 2015.[22] By the end of 2015, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife estimated that the total had grown to a minimum of 110 wolves.[25]

Sometime in 2016, OR-7 and his mate added two new pups to the Rogue Pack, bringing the total number of wolves in the pack to nine.[2]

As of November 2016, biologists are attempting to capture OR-7 so they can replace the GPS tracking collar to continue monitoring and alert ranchers when the pack is near. Four steer were killed by the pack in October in Wood River Valley. The scientists place four padded foot-hold traps each day in the western Klamath County area where he was last seen on trail cameras. If the weather turns much colder, they would have to postpone trapping until spring to protect against endangering a trapped animal.[30]

California wolves

Scant physical evidence exists of earlier wolf populations in California. Natural history museums in the state hold only two specimens of wild wolves from the 20th century, one of which is the 1924 wolf, and none from the 19th century. On the other hand, separate words for "wolf" and "coyote" as well as stories and ceremonies involving wolves are found in many indigenous cultures that have existed in northern, central, and southern California since before 1800.[31]

Although OR-7 was the first gray wolf to visit California in nearly 100 years, other wolves have since started a family in Siskiyou County, just south of the Oregon–California border. On August 20, 2015, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife released a photo of the Shasta Pack, consisting of two adults and five pups. The Shasta Pack breeding pair came from the same pack as OR7, making them his siblings. The adults are thought to have entered California from Oregon.[32]

In early November 2016, one of OR7's sons from the Rogue Pack was sighted in California with a female wolf.

Reaction

OR-7's migration captured the attention of viewers around the world after the story "went viral" in early December 2011.[8] On January 4, 2012, OR-7 was named "Journey" through an art and naming competition for children sponsored by Oregon Wild.[33] The conservation group acknowledged the naming contest was part of an effort to make the wolf "too famous to kill".[4] Steve Pedery, conservation director of Oregon Wild, said of the wolf: "Journey is the most famous wolf in the world. It is not surprising that the paparazzi finally caught up with him."[4]

German-born filmmaker Clemens Schenk, who lives in Bend, has created a documentary, OR7: The Journey. A look-alike wolf from Wolf People, an Idaho reserve, is the star of the film, which includes interviews with wolf experts as well as a woman who encountered OR-7 in the wild. The initial screening of the documentary occurred on May 25, 2014, at the Hollywood Theatre in Portland.[34]

Livestock losses

In early October 2016, wolves killed two calves in Klamath County and injured a third. The area in which the calves were killed is frequented by the Rogue Pack, but Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife officials could not immediately confirm that Rogue Pack wolves were involved.[35]

See also

References

- ↑ Elgin, Beckie (October 9, 2016). "Book Review: Wolf Advocate's Memoir Filled with Insight and Awe". The Oregonian. p. 8.

- 1 2 "Wolf Pack Grows As OR-7 Slows Down". Daily Tidings. August 1, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ↑ "OR-7 – A Lone Wolf's Story". California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "OR-7, Rare Gray Wolf That Crossed Into California, Likely Photographed". The Huffington Post. January 4, 2012. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- 1 2 "Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management Plan 2011 Annual Report" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ↑ Cockle, Richard (February 12, 2012). "Male Wolf OR-9 from Imnaha Pack Killed by Idaho Hunter with Expired Tag". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon: Advance Publications. ISSN 8750-1317. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Wandering Wolf Back in Oregon". The Observer. La Grande, Oregon. March 5, 2012. OCLC 30722076. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Freeman, Mark (February 23, 2012). "Wandering Wolf OR-7 Moves Within 10 Miles of Oregon". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon: Dow Jones Local Media Group. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- 1 2 Cockle, Richard (March 2, 2012). "OR-7 Returns to Oregon Apparently Still Looking for Love". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon: Advance Publications. ISSN 8750-1317. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ↑ Trail, Pepper (January 25, 2012). "The Romantic, Post-apocalyptic Journey of Wolf OR-7". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon: Advance Publications. ISSN 8750-1317. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ↑ Lee, Renee (January 18, 2012). "California Welcomes Wild Wolf for First time in 87 Years". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- 1 2 Kane, Will (March 3, 2012). "California Wolf Is Back in Oregon". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. ISSN 1932-8672. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ↑ Boxall, Bettina (March 3, 2012). "Wandering Gray Wolf Leaves California, Returns to Oregon". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. ISSN 0458-3035. OCLC 3638237. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ↑ Cockle, Richard (December 7, 2012). "OR-7's Biological Clock Ticking As He Moves to Lower Ground for Winter". The Oregonian. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Weiser, Matt (June 4, 2014). "Meet Wolf OR7's New Pups; California Moves to Protect Species". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- 1 2 "GPS Collar Stops Tracking Oregon's OR-7 Wolf". The Oregonian. October 31, 2015. p. A5.

- ↑ Swart, Cornelius (June 4, 2014). "Biologists Think Wolf OR-7 Has Pups in S. Ore.". KGW. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ↑ Terry, Lynn (May 12, 2014). "Oregon Wolf OR-7 Appears to Have Found a Mate After 3-Year Journey". The Oregonian. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ↑ La Ganga, Maria L. (May 14, 2014). "OR7, The Wandering Wolf, Looks for Love in All the Right Places". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. ISSN 0458-3035. OCLC 3638237. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- 1 2 "Wolf Program Updates". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ↑ Barnard, Jeff (January 8, 2015). "Oregon's Wandering Wolf, OR-7, Gets Official Pack Status". ABC News. ABC News Internet Ventures. Associated Press. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- 1 2 3 House, Kelly (July 8, 2015). "OR-7 and His Mate Raise More Pups". The Oregonian. p. A4.

- ↑ Associated Press (August 6, 2015). "Oregon's Famed OR-7 Adds at Least 2 Pups to Its Pack". The Oregonian. Retrieved August 7, 2015 – via Oregon Live.

- ↑ Barnard, Jeff (January 8, 2015). "Oregon's Wandering Wolf, OR-7, Gets Official Pack Status". ABC News. ABC News Internet Ventures. Associated Press. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- 1 2 "Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management: 2015 Annual Report" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. pp. 2–5. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Newsmaker: OR-7". The Oregonian. April 8, 2006. p. A5.

- ↑ House, Kelly (January 14, 2015). "Another Wolf Spotted in S. Oregon". The Oregonian. p. A9.

- ↑ "Wolves in Oregon". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. January 7, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Areas of Known Wolf Activity" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ↑ Mark Freeman (November 4, 2016). "Feds try to collar OR-7 again". Mail Tribune. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ↑ Marris, Emma. "Return of the Wild" (in The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2016). Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing: 195–202. ISBN 978-0-544-74899-6. ISSN 1530-1508.

- ↑ House, Kelly (August 20, 2015). "California Has Its First Wolf Pack in More Than 100 Years". The Oregonian. Oregon Live. Retrieved August 23, 2015 – via Advance Digital.

- ↑ "Don't Stop Believing...The Journey of OR-7". Oregon Wild. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ↑ Terry, Lynne (May 21, 2014). "Documentary of Oregon's Wandering Wolf, OR-7, Screened at Hollywood Theatre". The Oregonian. Oregon Live – Advance Digital. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ↑ Hernandez, Tony (October 12, 2016). "OR-7's Pack Suspected in 3 Attacks on Cattle". The Oregonian. p. A12.

External links

- Map of wolf packs in Oregon in 2014 (PDF) by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

- Photo of OR-7 in southern Oregon, November 14, 2011