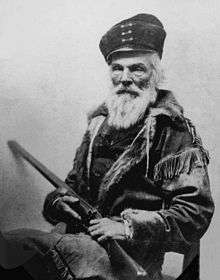

Joseph R. Walker

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.

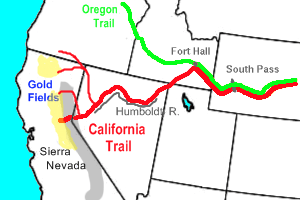

Joseph R. Walker[lower-alpha 1] (December 13, 1798 — October 27, 1876) was a mountain man and experienced scout. He established the segment of the California Trail, the primary route for the emigrants to the gold fields during the California gold rush, from Fort Hall, Idaho to the Truckee River. The Walker River and Walker Lake in Nevada were named for him by John C. Frémont.[lower-alpha 2]

Early Years

Walker was born in Roane County, Tennessee, the fourth child of seven born to Joseph and Susan Willis Walker.[3] In 1819, the family emigrated to Missouri,[4] settling west of Fort Osage.[5] In 1820, he traveled to Santa Fe and was detained for a short while by Spanish authorities.[6] He may have become one of the "Taos trappers" trapping beaver in the Spanish/Mexican[lower-alpha 3] territory of Alta California, then working on the Santa Fe Trail from Missouri to Santa Fe with "Old" Bill Williams. He returned to Missouri and in 1827 was appointed sheriff of Jackson County.[7]

Explorations of California and the Great Basin

In 1830, Walker was driving horses to Fort Gibson in Oklahoma, where he met Benjamin Bonneville.[8] Walker wanted to explore the American frontier, and Bonneville offered him an opportunity to join him in his expeditions. In 1832, Walker left from Fort Osage with Bonneville[9] and 110 other men, traveling to the Green River in Wyoming.[10]

In 1833, Bonneville sent Walker in command of a party of men, including Old Bill Williams, from the Green River to explore the Great Salt Lake and to find an overland route to California.[11] They left on July 27 and eventually discovered a route along the Humboldt River across present-day Nevada. They followed it to the Humboldt Sink,[lower-alpha 4] then made their way to present day Genoa, Nevada at the base of the Sierra Nevada. They began their ascent of the Sierras by traveling up the west fork of the Carson River to Hawkins Peak. At that point, they began wandering, trying to find a path to a dividing ridge and down the western slope. They finally made their way to the headwaters of the Stanislaus River, and descended on the ridgeline north of the river canyon. They eventually made it to the river itself, then followed it down to the Central Valley of California.[lower-alpha 5]

On February 14, 1834, Walker and his party of fifty two men left on their return trip from California, crossing back over the Sierra Nevada through one of the southern passes.[lower-alpha 6] The group made it to Owens Valley on May 1, 1834.[14] and traveled up it but became impatient to turn east. They crossed out of the valley on May 10, but soon became alarmed by the lack of water.[15] They went back west to the base of the Sierras, and traveled north to the Humboldt Sink, then traveled back to Rocky Mountains the way they had come the previous summer.

At some point in the ensuing years, Walker took a Shoshone wife.[16]

In 1840 Walker and a band of followers made the first known north to south crossing of the eastern Great Basin by Americans. Starting from Brown's Hole along the Green River, Walker and his men crossed the Wasatch Range to the Sevier Lake and traveled south to the upper Virgin River which they descended until reaching its confluence with the Colorado River. From the Colorado, they crossed the Mojave Desert to Los Angeles where Walker sold 417 pounds of beaver pelts to Abel Stearns, a prominent American expatriate living in Los Angeles, who became Walker's business agent in purchasing horses. Walker left California with a hundred mares and an unknown number of mules.[16]

Emigrant Leader

After travelling to California in the Bartleson–Bidwell Party of 1841 Joseph B. Chiles returned to western Missouri and organized the first wagon train of California bound emigrants in 1843.[lower-alpha 7] At Fort Laramie, Chiles hired Walker to guide the wagon train to California for $300. In August, at Black's Fork of the Green River, the party stopped to rest the animals and hunt, trying to stock dried meat for the trail. They were marginally successful, and being able to only acquire four head of cattle at Ft. Hall, Walker and Chiles decided to split the party in order to make best use of the remaining provisions. After leaving Fort Hall on September 16, Chiles took 13 men on horseback to Fort Boise for further provisions. If food was not available, he was to cross the Sierra Nevada in the vicinity of the Truckee River, proceed to Sutter's Fort for food, and bring it across the Sierra to Humboldt Sink where Walker and the wagon train would be waiting.[lower-alpha 8] Once reunited they would proceed south through the Owens Valley, along the eastern scarp of the Sierra Nevada to a southern pass, possibly Oak Creek Pass where Walker believed the wagons could cross.[lower-alpha 9] The Chiles group was unable to obtain provisions at Fort Boise and circumvented the Sierra Nevada far to the north, rather than crossing at the Truckee River. Chiles reached Sutter's Fort on 11 November. Walker's group left the Humboldt Sink about 1 November and traded horseshoe nails for fish with the Paiute at what would later be known as Walker Lake. Possibly because of inadequate forage (it was a drought year) the animals were unable to pull the wagons beyond Owens Lake where the wagons were abandoned along with a disassembled saw mill (see also Bancroft 1886:IV:392 395). The party proceeded on foot and crossed the summit of the Sierras on December 3, 1843.[16] Thereafter they crossed the San Joaquin Valley (the southern half of the Central Valley) and the Coast Range and wintered pleasantly in Peachtree Valley on the headwaters of a tributary to the Salinas River in the Salinas Valley (Bancroft 1886:IV:395). About the journey Gilbert states:

- "The overland caravan had done no true exploring but had laid down 500 miles of what was to become the California Trail."[17]

The trail segment referred to appears to extend from Fort Hall (Idaho) to the Truckee River (Nevada and California).[18]

Scouting with Frémont

After the expedition dispersed, Walker once again presented his passport to the authorities and was granted permission to trade. As before, he left southern California with a herd of horses and mules in April 1844 along the Old Spanish Trail and overtook John C. Frémont's second military topographic expedition (his first to California) somewhere beyond Las Vegas. The two had met previously in 1842 at Independence, Missouri, when Walker declined Frémont's invitation to guide the expedition. Walker's group traveled with Frêmont to Bent's Fort (Colorado) where they went their separate ways. In 1845 by prearrangement, Walker, with his wife and retainers, joined Frémont's third government expedition at White River (eastern Utah) bound for California and Oregon. Frémont had recruited Bill Williams and Kit Carson but Walker was appointed the chief guide. Walker and his followers had previously camped with one of the first U.S. dragoon units to patrol the emigration trails and was described as follows by Captain Philip St. George Cooke:

- "This afternoon Mr. Walker, whom we met at Independence Rock, visited our camp: he has picked up a small party at Fort Laramie; and wild looking creatures they are white and red. This man has abandoned civilization, married a squaw or squaws, and prefers to pass his life wandering in these deserts; carrying on, perhaps, an almost nominal business of hunting, trapping and trading but quite sufficient to the wants of a chief of savages. He is a man of much natural ability, and apparently of prowess and ready resource."[19]

Walker led the main body of the expedition down the Humboldt River to Walker Lake where they met Frémont and a smaller group who had taken a more southerly route after leaving the vicinity of the Great salt Lake. The party again divided, with Walker taking the main body to the current location of Lake Isabella in December while Frémont and a small group crossed the Sierra Nevada in the vicinity of Truckee River, eventually reaching Sutter's Fort (California). The two parties missed their planned rendezvous along the Kings River in the San Joaquin Valley but were reunited in February 1846.

Later life

In 1862-63, Walker led a well-known gold-hunting expedition of 34 men into the mountains of central Arizona, near what is now the city of Prescott.[20] The company struck gold along the Hassayampa River and Lynx Creek, which was the impetus for subsequent white settlement in the area. The village of Walker, Arizona is named for him.

Walker returned to the family base of Manzanita Ranch in Contra Costa County, California in 1867.[21] He died there on October 27 1876, and is buried in the Alhambra Cemetery in Martinez, California.[22]

Footnotes

- ↑ The R. stood for Rutherford, but is also found as Reddford, Reddeford, and Redeford. "Rutherford" came from his great-grandmother's, Kathleen Rutherford Walker, line,[1] and not his mother's, as incorrectly stated in some sources.

- ↑ Oak Creek Pass was also named for him by Frémont,[2] but the designation was later changed to another pass to the north, now known as Walker Pass.

- ↑ Mexico declared independence from Spain in 1822

- ↑ The approach to the Sierra via the Humboldt River route later became known as the California Trail, the primary route for the emigrants to the gold fields during the California gold rush.

- ↑ After Walker's death, he was eulogized as being the leader of the first group of Europeans to "gaze upon Yosemite Valley." Subsequent historians, Francis P. Farquhar in particular, tried to recreate a route that would have Walker's group start their Sierra ascent at present day Bridgeport, to the rim of Yosemite, then descending between the Tuolumne and Merced River drainage.[12] Scott Stine, Professor Emeritus in the Department of Anthropology, Geography, and Environmental Studies at California State University, East Bay, conducted an extensive study of Zenas Leonard's, a member of the group, journal, in comparison with the geography of the Sierras and reasonable distances the group might have traveled each day, and determined that Walker's group's route could not have traveled as far south as Yosemite, and instead proposed the northern route described in the body of the article.

- ↑ Which pass Walker used is disputed. While it is generally accepted that the Native American guides he engaged took him over what is today known as "Walker Pass", G. Andrew Miller avers that the party crossed over 50 miles north of there, descending the eastern Sierras at Haiwee Pass.[13]

- ↑ The Bartleson-Bidwell Party had to abandon their wagons at the Great Salt Lake and had used pack animals to cross the Sierras at Ebbetts Pass

- ↑ Another account (Bancroft 1886:IV:394 395) places the proposed rendezvous at the west end of Walker Pass. The Walker party reached the Humboldt Sink on approximately October 22, 1843.

- ↑ Haiwee Pass was too steep for wagons, and it was probably too late in the year to cross such a higher (8500') pass.

Citations

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 25

- ↑ Frémont, John Charles (1970). Jackson, Donald; Spence, Mary Lee, eds. The Expeditions of John Charles 1 Frémont. Vol. 1: Travels from 1838 to 1844. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 657–57, 668.

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 49

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 58

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 62

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 71

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 87

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 96-7

- ↑ O'Meara, James (1 Dec 1915). "Joseph R. Walker". The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society. 16. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 105

- ↑ Gilbert, pp. 125-27

- ↑ History of the Sierra Nevada (1946)

- ↑ Miller, p. 123

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 144

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 145

- 1 2 3 Rudo, Section 8, p. 7

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 197

- ↑ Rudo, Section 8, p. 8

- ↑ Gilbert p. 210

- ↑ Jack Swilling and Joseph Walker's Arizona Adventure Part I. Sharlot Hall Museum

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 282

- ↑ http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=5755541

Major References

- Gilbert, Bil (1985) [1983]. Westering Man: The Life of Joseph Walker. Tulsa: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806119349.

- Miller, G. Andrew (2004). Joseph R. Walker, California Expedition 1833-34. Silver Spur Publishing.

- Rudo, Mark O. (September 26, 1989). "Walker Pass" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places - Nomination and Inventory. National Park Service. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.