John Hazelwood

| John Hazelwood | |

|---|---|

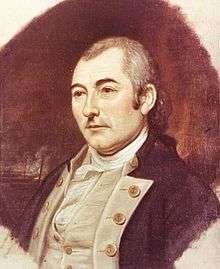

Commodore John Hazelwood by Charles Wilson Peale | |

| Born |

1726 (exact date unknown) England |

| Died |

March 1, 1800 Philadelphia |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1775–1785 |

| Rank | Commodore |

| Signature |

|

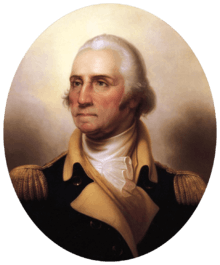

John Hazelwood (1726 – March 1, 1800)[lower-alpha 1] served as a Commodore in the Pennsylvania Navy and Continental Navy and was among the most noted naval officers during the American Revolutionary War. Born in England about 1726, he became a mariner and settled in Philadelphia early in life, became married and had several children. Promoted to Commodore during the Philadelphia campaign, he also became commander of Fort Mifflin while it was under siege by the British. Throughout the campaign Hazelwood and General Washington were in frequent communication with letters.[lower-alpha 2] During the weeks spent engaging the British navy on the Delaware River Hazelwood innovated many naval tactics, kept the British navy at bay for weeks and played a major role in the development of riverine warfare for the American navies. Recommended by Washington and his council, Hazelwood was chosen to lead a large fleet of American ships and riverboats up river to safety. For his bravery and distinguished service Congress awarded him with a ceremonial military sword, while the famous presidential artist Charles Peale found Hazelwood worthy enough to paint his portrait. After the Revolution Hazelwood lived out his remaining years in Philadelphia.

Personal life

In the years before the American Revolution broke out Hazelwood served as a captain on various merchant vessels, most often shipping goods between Philadelphia and London. In 1772 he became one of the founders of the Saint George society of Philadelphia.[1] Hazelwood married his first wife, Mary Edgar, who died in 1769 at age 36. In 1771 he married the widow Ester Leacock. His first and second marriage brought him five children. His first child, Thomas, by his first wife, became a captain in the Pennsylvania Navy during the Revolution. His son, John, was a lieutenant in an artillery company serving in the Pennsylvania Western Expedition in 1794. John Jr. died in action only weeks after his father's death in 1800 and was buried next to him. Hazelwood was a vestryman of Christ Church in Philadelphia from 1779 to 1783.[2]

Naval career

A commissioned officer in the Pennsylvania Navy,[lower-alpha 3] Commodore Hazelwood commanded all naval vessels of the Pennsylvania and Continental navies on the Delaware River. In the years before the American Revolution he commanded a number of ships including the Susanna and Molly in 1753, the Greyhound in 1762, the Monckton in 1763, the Sally in 1771 and the Rebecca in 1774.[4] The earliest known record of Hazelwood's service in the American Revolutionary War is 1775.[5] Hazelwood was appointed supervisor of building and management of fire-vessels in December, 1775, and by October 1776 was promoted to Commodore in the Pennsylvania Navy.[6]

Early Revolution

During the Revolutionary War against the British Hazelwood played an important role in the planning of the various American river defenses. During the months prior to the British advance on Philadelphia he oversaw the development and construction of fire-vessels,[lower-alpha 4] which were used in conjunction with the many river obstructions, Cheval de frise, that were also developed for use in the Delaware River.[5] The designs proved effective and in July, 1776, Hazelwood was immediately sent to Poughkeepsie, New York, (one among a committee of three) with orders to plan for and construct similar river obstructions to prevent British marine navigation on the upper Hudson River;[5]

At the time Commodore John Barry was the senior navy captain in Philadelphia and the visible choice to command both the Pennsylvania and Continental navies, but command was given to Hazelwood, already in command of the Pennsylvania Navy.[7] Hazelwood was soon promoted to Commodore of both the Pennsylvania and Continental navies in the Delaware River some time in 1777 but the exact date is not known.[4][8]

Hazelwood planned for and participated in the defense of the Delaware River approach to Philadelphia in 1777 before and during the Siege of Fort Mifflin, which lasted approximately three weeks. He was soon appointed to oversee the building of and command of fire rafts, which were used to prevent passage of British ships bringing badly needed supplies to British in Philadelphia. In planning for the fort's defense the Committee of Safety authorized the construction of war-ships, a flotilla of fire-rafts, floating batteries and the construction of river obstacles which were floated into place and sank. Construction of ten fire-rafts reached completion by December 27 where Hazelwood was appointed commander of this fleet of rafts. In the following May the Committee of Safety selected Hazelwood "to survey the river from Billingsport to Fort Island and the East side across from the island.[5]

Hazelwood was given a scouting assignment on September 19, with orders to move the American fleet to Darby Creek to observe British strength, vessels and activity at Chester. Various American rivercraft also engaged and harassed the British at various points along the river. In the process Hazelwood obtained much information about the British presence, which was copied and passed on to other commanders in the greater area.[8]

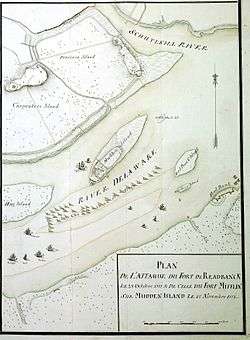

Philadelphia finally fell on September 26 and Vice Admiral Howe and the British army entered the city, however they were low on ammunition and supply and had not established a naval supply route along the heavily defended Delaware River. In the days that followed the British began fortifying the shore surrounding the city and at the mouth of the Schuylkill River, bringing in heavy guns and supplies. During October the American fleet engaged British naval vessels and gave support to American forts along the river. Hazelwood frequently ordered galleys to deter British ships away from Billingsport.[9] Hazelwood's galleys kept up a disrupting fire while others patrolled the waters around Fort Mifflin. On October 9, Hazelwood's fleet of galleys attacked the British battery at Webb Ferry. Two days later, Hazelwood landed a body of militia on Carpenter's Island, assaulting the middle battery and capturing fifty men and two officers. A second assault on British batteries was attempted the next day but was met with heavy fire, causing the American vessels to withdraw after receiving heavy losses.[10]

On October 22 the British launched naval assaults on positions below the fort in concert with a ground assault on Fort Mercer.[9] In a letter of October 23, 1777, to General Washington, a fatigued Hazelwood reported that on that morning his fleet had driven the British fleet down river and forced one of its frigates ashore where the vessel accidentally exploded somehow. He reported also that his fleet was in need of reinforcements but maintained that he would not draw any men from the fort, as they were badly needed there.[11] At this time the Marine Committee of Congress ordered Hazelwood and his second in command, Captain Charles Alexander, to take a small fleet of vessels and fire on British positions in and about Philadelphia. During the exchange of fire, the American frigate USS Delaware, commanded by Alexander, received heavy damage and was run aground where Alexander, his crew and ship were soon captured.[12][13] When the tide had risen the Delaware was brought back to Philadelphia. On October 23, Hazelwood's gunboats and galleys maintained a harassing fire on British men-of-war trying to dismantle river obstructions. In the process the British frigate Merlin and ship of the line Augusta grounded, forcing its crew to burn them. On October 27 Washington advised Hazelwood that he should send a party to the waterfront at Philadelphia at night and burn the captured Delaware but Hazelwood thought the prospect too risky and declined.[14]

Though the capture of the Delaware was a major tactical loss, Hazelwood now realized that attacking British positions and vessels about Philadelphia with smaller vessels more suitable to river navigation was a feasible effort.[15] During the weeks Hazelwood had engaged the British on the Delaware River he innovated and developed many naval riverine tactics and introduced the idea of small boat riverine warfare to the American navy.[16] However, in the face of mounting British forces Hazelwood's fleet eventually proved too small to maintain an effectual fire while maintaining a defense for forts Mifflin and Mercer.[10]

Siege of Fort Mifflin

Hazelwood played a major role in the American effort in keeping British ships from reaching Philadelphia by way of the Delaware River. In the months leading up to the British siege of Fort Mifflin Washington's headquarters at this time was located north of Philadelphia in Whitemarsh where he maintained frequent communication with Hazelwood, sending him reports, orders and advice.[17][lower-alpha 5] Fort Mifflin, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith, was located on an island in the middle of this river and was a key point of defense for the Americans. The fortress, along with Fort Mercer on the east bank, were the only obstacles preventing the British naval access to Philadelphia. Vice Admiral Howe dispatched a message to Hazelwood requesting that he surrender the Pennsylvania fleet, allowing Howe and his fleet to control the Delaware Bay, where Hazelwood was allegedly promised a pardon from the King if he cooperated. Hazelwood refused the dubious offer, declaring that he would "defend the fleet to the last".[1][18]

The successful siege upon the stone and earthen fort required the prolonged bombardment by the British Navy under the command of Admiral Howe, also involving land batteries, lasting from September 26 to November 16, 1777. The standoff and defense of the fort allowed time for Washington and the Continental Army to safely deploy for the Battle of White Marsh and its subsequent withdrawal to Valley Forge. Washington received warnings from Generals Porter and Lee, stationed on the Schuylkill River at Philadelphia, that the British were making communication runs across the river at night using small boats. In a letter of November 4, Washington advised Hazelwood to do all he could to stop the activity.[19] Hazelwood's efforts to end the communications were less than effectual. Several days before the fall of the fort Washington dispatched another letter to Hazelwood inquiring about his status, urging that if at all possible to remain at his station with the fleet after the fort has fallen so as to hinder and prolong British operations long enough to allow the river to freeze over, preventing passage of supply ships into Philadelphia until the spring thaw.[20]

After weeks of almost constant bombardment from British ships and batteries and receiving extensive damage and heavy casualties, Fort Mifflin was finally abandoned on November 15, while the fort's flag was left there and remained flying. Capture of the fort was finally effected on November 16, leaving only Fort Mercer on the Red Bank of New Jersey to defend the river. Two days later, with 7,000 British troops led by General Cornwallis and with General Howe's 1000 troops marching north to Fort Mercer, Hazelwood scuttled many of the smaller ships and galleys located there while Captain Christopher Greene and the American garrison abandoned the fort on November 20 leaving it to the advancing British.[21] Two days later General Washington called a Council of War, meeting with several of his generals on board one of Hazelwood's ships. During the assembly Washington's council recommended that Commodore Hazelwood lead the effort "with the first favorable wind", and get the American ships and supplies in the area safely up river just past Burlington, New Jersey. On the night of the 21st Hazelwood and the American naval fleet managed to pass by the British who were busy securing their position in Philadelphia, with no shots fired by them to stop passage of Hazelwood and the American fleet.[22][23]

Soon after the fall of Forts Mifflin and Mercer Washington and other commanders sought an explanation about what lead to their capture. Washington had sent General Varnum to Fort Mifflin in November to quell the frequent command disputes between garrison and naval commanders with little success. Varnum faulted himself and offered his apologies to Washington. Hazelwood and Smith, already rivals, laid the blame on each other. Exchanges between the two became increasingly heated and bitter, while each embarked on campaigns in Congress and the Pennsylvania Council for the purpose of exonerating themselves of any shortcomings, while the blaming from both continued. At one point their exchanges became so heated that Varnum and other officers had to intervene to prevent a duel.[lower-alpha 6][24]

In June 1778 the British were ordered to abandon Philadelphia and defend New York. In August The Assembly of Pennsylvania decided that a large State navy was no longer necessary and recommended that most of its ships and supplies be disbanded. During the transition Commodore Hazelwood, who was the last to hold this rank, was discharged along with a number of other officers.[22] Widely trusted and respected in Pennsylvania and elsewhere, he was appointed Receiver of Provisions for the Pennsylvania militia.

Later Revolution

In February 1779, urged by the Board of War and merchants, Hazelwood was part of a committee of six defense experts chosen to survey the Delaware River, and represented the State of Pennsylvania in this effort. They were accompanied by Continental Army chief engineer Du Portail and Baron Von Steuben. Hazelwood and the defense Committee crossed the Delaware from Gloucester Point in south Philadelphia to New Jersey at Red Bank. There they embarked on horseback across Gloucester County to inspect defense works at Billingsport. From there they crossed the river to Mud island and then returned to Philadelphia with advice for General Washington as how best to defend the river.[25] Later that year Hazelwood became a member of a public committee chosen to meet in Philadelphia to raise money to help provide for the Army. In 1780 he became the Commissary of Purchases for the Continental Army, considered an office of great trust and responsibility over the great sums of money involved.[22]

Post Revolution

On April 11, 1785, Hazelwood was selected to be one of the port wardens in Philadelphia.[2]

Later life

Relatively less is known about Hazelwood's life after the American Revolution. The renowned patriot and artist Captain Charles Wilson Peale considered Hazelwood worthy of one of his portraits, which was later acquired by the city of Philadelphia and was hung in Independence Hall. John Hazelwood died in Philadelphia at age 74 on March 1, 1800. He was buried on March 3 in the graveyard of Saint Peter's Church.[2]

Legacy

For Hazelwood's role in the War for Independence, the Continental Congress awarded him a handsome silver and gold enameled sword, one of only fifteen awarded during the Revolution, all swords being identical in design. Hazelwood's sword now hangs in the collection of the Naval Historical Foundation.[26]

USS Hazelwood (DD-107) was named in his honor.[26]

See also

- Other notable naval commanders of the time : John Paul Jones • Commodore John Barry • Commodore Stephen Decatur • Admiral David Farragut • Admiral Richard Howe • Admiral Horatio Nelson

- List of Revolutionary War naval battles

- Bibliography of George Washington : Fitzpatrick, 1933 v.10, letters to Hazelwood from Washington

- Battle of Brandywine

- List of American Revolutionary War battles

- Bibliography of early American naval history

Notes

- ↑ Exact date of birth unknown

- ↑ Most of Washington's and Hazelwood's letters have been published. See : Bibliography of George Washington#Primary sources

- ↑ The 48-ship Pennsylvania state fleet comprised a variety of generally smaller vessels, including one frigate, a brig, several sloops and a larger number of armed galleys.[3]

- ↑ Smaller boats or rafts, laden with combustionable materials

- ↑ See: Fitzpatrick, 1933, The Writings of George Washington, volumes 9 & 10.

- ↑ During this period duels between officers, despite any laws against the practice, were somewhat common, sometimes causing a shortage of experienced officers.

References

- 1 2 History Central article: John Hazelwood

- 1 2 3 Leach, 1902, p. 6

- ↑ USHistory.org: Pennsylvania State Navy

- 1 2 Leach, 1902, p.1

- 1 2 3 4 Leach, 1902, p.2

- ↑ History Central, 2016

- ↑ McGrath, 2015, pp. 165–166

- 1 2 Dunnavent, 1998, p. 31

- 1 2 Dorwart, 1998, pp. 36–38

- ↑ Hazelwood, Sparks, 1853, pp. 12–13

- ↑ Dorwart, 2008, p.144

- ↑ Dunnavent, 1998, pp. 31–33

- ↑ Dornwart, 1998, pp. 41–42

- ↑ Dunnavent, 1998, p. 37

- ↑ Dunnavent, 1998, p. 38

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, 1933, v.9, numerous letters to Hazelwood at this time: See Table of Contents.

- ↑ Leach, 1902, pp. 3–4

- ↑ Washington, Fitzpatrick (Ed), 1933, p. 9

- ↑ Washington, Fitzpatrick (Ed), 1933, pp. 59–60

- ↑ Dorwart, 2008, p.146

- 1 2 3 Leach, 1902, p. 5

- ↑ Lockwood (ed). 1895, pp. 22–23

- ↑ Dorwart, 1998, p. 54

- ↑ Dorwart, 1998, p. 62

Bibliography

- Dorwart, Jeffery M. (1998). Fort Mifflin of Philadelphia: An Illustrated History. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1644-8.

- —— (2008). Invasion and Insurrection: Security, Defense, and War in the Delaware Valley, 1621–1815. Associated University Presse,. ISBN 978-0-8741-3036-2.

- Dunnavent, R. Blake (1998). "Muddy Waters: A History of the United States Navy in Riverine Warfare and the Emergence of a Tactical Doctrine, 1775 – 1989". Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- Hazelwood, John (1853). Jared Sparks, ed. Correspondence of the American Revolution being letters of Eminent Men to George Washington, volume II. Little, Brown, and Company.

- Hickman, Kennedy. "American Revolution: Siege of Fort Mifflin". About.com. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- Leach, Josiah Granville. "Commodore John Hazlewood, Commander of the Pennsylvania Navy in the Revolution". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1902), pp. 1–6 and The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. JSTOR 20086007.

- Lockwood, Mary S. (1895). Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine, Volume 7. National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

- McGrath, Tim (2015). Give Me a Fast Ship: The Continental Navy and America's Revolution at Sea. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-4514-1611-7.

- McGuire, Thomas J. (2007). The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume I. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0178-5.

- McGuire, Thomas J. (2007). The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume II. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-4945-9.

- "The Pennsylvania State Navy". USHistory.org. 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- Washington, George (1933). Fitzpatrick, John C., ed. The writings of George Washington from the original manuscript sources, 1745–1799. v.9. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- —— (1933). Fitzpatrick, John Clement, ed. The writings of George Washington from the original manuscript sources, 1745–1799. v.10. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- "USS HAZELWOOD (DD-107)". NavSource. NavSource Naval History. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

Further reading

- Jackson, John W. (1977). The Delaware Bay and river defenses of Philadelphia 1775–1777. Philadelphia Maritime Museum.

- Whiteley, William Gustavus (1875). The revolutionary soldiers of Delaware. Wilmington, Del., James & Webb, printers.