John Gould

| John Gould | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

14 September 1804 Lyme Regis, Dorset |

| Died |

3 February 1881 (aged 76) Bedford Square, London |

| Resting place | Kensal Green cemetery |

| Nationality | British |

| Fields | Ornithology |

| Known for | Illustrated monographs on birds |

| Influences | Charles Darwin |

John Gould FRS (/ɡuːld/; 14 September 1804 – 3 February 1881) was an English ornithologist and bird artist. He published a number of monographs on birds, illustrated by plates that he produced with the assistance of his wife, Elizabeth Gould, and several other artists including Edward Lear, Henry Constantine Richter, Joseph Wolf and William Matthew Hart. He has been considered the father of bird study in Australia and the Gould League in Australia is named after him. His identification of the birds now nicknamed "Darwin's finches" played a role in the inception of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection. Gould's work is referenced in Charles Darwin's book, On the Origin of Species.

Early life

Gould was born in Lyme Regis, Dorset, the first son of a gardener. He and the boy probably had a scanty education. Shortly afterwards his father obtained a position on an estate near Guildford, Surrey, and then in 1818 Gould became foreman in the Royal Gardens of Windsor. He was for some time under the care of J. T. Aiton, of the Royal Gardens of Windsor. The young Gould started training as a gardener, being employed under his father at Windsor from 1818 to 1824, and he was subsequently a gardener at Ripley Castle in Yorkshire. He became an expert in the art of taxidermy. In 1824 he set himself up in business in London as a taxidermist, and his skill helped him to become the first Curator and Preserver at the museum of the Zoological Society of London in 1827.[1][2]

Research and works published

_by_John_Gould.jpg)

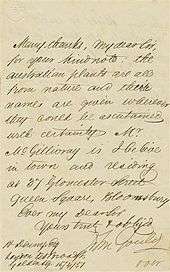

Gould's position brought him into contact with the country's leading naturalists. This meant that he was often the first to see new collections of birds given to the Zoological Society of London. In 1830 a collection of birds arrived from the Himalayas, many not previously described. Gould published these birds in A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains (1830–1832). The text was by Nicholas Aylward Vigors and the illustrations were lithographed by Gould's wife Elizabeth, daughter of Nicholas Coxen, of Kent. Most of Gould's work were rough sketches on paper from which other artists created the lithographic plates.[3][4]

This work was followed by four more in the next seven years, including Birds of Europe in five volumes. It was completed in 1837; Gould wrote the text, and his clerk, Edwin Prince, did the editing. Some of the illustrations were made by Edward Lear as part of his Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae in 1832. Lear, however, was in financial difficulty, and he sold the entire set of lithographs to Gould. The books were published in a very large size, imperial folio, with magnificent coloured plates. Eventually 41 of these volumes were published, with about 3000 plates. They appeared in parts at £3 3s. a number, subscribed for in advance, and in spite of the heavy expense of preparing the plates, Gould succeeded in making his ventures pay, realizing a fortune. In 1838 he and his wife moved to Australia to work on the Birds of Australia. Shortly after their return to England, his wife died in 1841.[1][5]

Work with Darwin

When Charles Darwin presented his mammal and bird specimens collected during the second voyage of HMS Beagle to the Zoological Society of London on 4 January 1837, the bird specimens were given to Gould for identification. He set aside his paying work and at the next meeting on 10 January reported that birds from the Galápagos Islands which Darwin had thought were blackbirds, "gross-bills" and finches were in fact "a series of ground Finches which are so peculiar" as to form "an entirely new group, containing 12 species." This story made the newspapers. In March, Darwin met Gould again, learning that his Galápagos "wren" was another species of finch and the mockingbirds he had labelled by island were separate species rather than just varieties, with relatives on the South American mainland. Subsequently, Gould advised that the smaller southern Rhea specimen that had been rescued from a Christmas dinner was a separate species which he named Rhea darwinii, whose territory overlapped with the northern rheas. Darwin had not bothered to label his finches by island, but others on the expedition had taken more care. He now sought specimens collected by captain Robert FitzRoy and crewmen. From them he was able to establish that the species were unique to islands, an important step on the inception of his theory of evolution by natural selection. Gould's work on the birds was published between 1838 and 1842 in five numbers as Part 3 of Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, edited by Charles Darwin.[6][7]

Research in Australia

In 1838 the Goulds sailed to Australia, intending to study the birds of that country and be the first to produce a major work on the subject. They took with them the collector John Gilbert. They arrived in Tasmania in September, making the acquaintance of the governor Sir John Franklin and his wife. Gould and Gilbert collected on the island. In February 1839 Gould sailed to Sydney, leaving his pregnant wife with the Franklins. He travelled to his brother-in-law's station at Yarrundi,[8] spending his time searching for bowerbirds in the Liverpool Range. In April he returned to Tasmania for the birth of his son. In May he sailed to Adelaide to meet Charles Sturt, who was preparing to lead an expedition to the Murray River. Gould collected in the Mount Lofty range, the Murray Scrubs and Kangaroo Island, returning again to Hobart in July. He then travelled with his wife to Yarrundi. They returned home to England in May 1840.

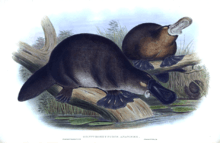

The result of the trip was The Birds of Australia (1840–1848). It included a total of 600 plates in seven volumes; 328 of the species described were new to science and named by Gould. He also published A Monograph of the Macropodidae, or Family of Kangaroos (1841–1842) and the three volume work The Mammals of Australia (1849–1861).[9][10]

Elizabeth died in 1841 after the birth of their eighth child, Sarah, and Gould's books subsequently used illustrations by a number of artists, including Henry Constantine Richter, William Matthew Hart and Joseph Wolf.

.jpg)

Hummingbirds

Throughout his professional life Gould had a strong interest in hummingbirds. He accumulated a collection of 320 species, which he exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851.[11] Despite his interest, Gould had never seen a live hummingbird. In May 1857 he travelled to the United States with his second son, Charles. He arrived in New York too early in the season to see hummingbirds in that city, but on 21 May 1857, in Bartram's Gardens in Philadelphia, he finally saw his first live one, a ruby-throated hummingbird. He then continued to Washington D.C. where he saw large numbers in the gardens of the Capitol. Gould attempted to return to England with live specimens, but, as he was not aware of the conditions necessary to keep them, they only lived for two months at most.

Other works

Gould published: A Monograph of the Trochilidae or Humming Birds with 360 plates (1849–61); The Mammals of Australia (1845–63), Handbook to the Birds of Australia (1865), The Birds of Asia (1850–83), The Birds of Great Britain (1862–73) and The Birds of New Guinea and the adjacent Papuan Islands (1875–88).

The Birds of Great Britain

The University of Glasgow, which owns a copy of Birds of Great Britain, describes John Gould as "the greatest figure in bird illustration after Audubon",[12] and auctioneers Sotherans describe the work as "Gould's pride and joy".[13]

Gould had already published some of the illustrations in Birds of Europe, but Birds of Great Britain represents a development of his aesthetic style in which he adds illustrations of nests and young on a large scale.

Sotherans Co.[14] reports that Gould published the book himself, producing 750 copies, which remain sought after both as complete volumes, and as individual plates, currently varying in price from £450 – £850. The University of Glasgow records that the volumes were issued in London in 25 parts, to make the complete set, between 1863 and 1873, and each set contained 367 coloured lithographs.

Gould undertook an ornithological tour of Scandinavia in 1856, in preparation for the work, taking with him the artist Henry Wolf who drew 57 of the plates from Gould’s preparatory sketches. According to The University of Glasgow [12] Gould’s skill was in rapidly producing rough sketches from nature (a majority of the sketches were drawn from newly killed specimens) capturing the distinctiveness of each species. Gould then oversaw the process whereby his artists worked his sketches up into the finished drawings, which were made into coloured lithographs by engraver William Hart.

There were problems: the stone engraving of the snowy owl in volume I was dropped and broken at an early stage in the printing. Later issues of this plate show evidence of this damage and consequently the early issue – printed before the accident – are considered more desirable.

The lithographs were hand coloured, and, in writing the introduction for the work, Gould states "every sky with its varied tints and every feather of each bird were coloured by hand; and when it is considered that nearly two hundred and eighty thousand illustrations in the present work have been so treated, it will most likely cause some astonishment to those who give the subject a thought."

The work has gathered critical acclaim: according to Mullens and Swann, Birds of Great Britain is "the most sumptuous and costly of British bird books", whilst Wood describes it as "a magnificent work". Isabella Tree writes that it "was seen – perhaps partly because its subject was British, as the culmination of [his] ... genius".[15]

In 2012 the rare book dealer Peter Harrington [16] described a complete edition of 5 volumes as follows:

5 volumes, folio (580 × 350 mm). Finely bound by Tuckett (binder to the Queen) in contemporary full green Morocco, spines elaborately gilt in compartments, raised bands, ruling and elaborate floral rolls to boards gilt, yellow coated endpapers, all edges gilt. 367 fine, handcoloured lithograph plates by Richter and Hart after Gould and Wolf, heightened with gum-Arabic.— Peter Harrington

Tributes

A number of animals have been named after Gould, including those in English such as the Gould's mouse.

Birds named after Gould include

- Gould's petrel (Pterodroma leucoptera)

- Gould's shortwing (Brachypteryx stellata)

- Gould's frogmouth (Batrachostomus stellatus)

- Gould's jewelfront (Heliodoxa aurescens)

- Gould's inca (Coeligena inca)

- Gould's toucanet (Selenidera gouldii )

- Dot-eared coquette (Lophornis gouldii )

- Olive-backed euphonia (Euphonia gouldi )

Two species of reptiles are named in his honor: Gould's monitor (Varanus gouldii ) and Gould's black-headed snake (Suta gouldii ).[17]

Gould's sunbird, or Mrs. Gould's sunbird, (Aethopyga gouldiae) and the Gouldian finch (Erythrura gouldiae) were named after his wife.[18]

A visit to Gould in his old age provided the inspiration for John Everett Millais's painting The Ruling Passion.

The Gould League, founded in Australia in 1909, was named after him. This organization gave many Australians their first introduction to birds, along with more general environmental and ecological education. One of its major sponsors was the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union.

In 1976 he was honoured on a postage stamp, bearing his portrait, issued by Australia Post. In 2009, a series of birds from his Birds of Australia, with paintings by H C Richter, were featured in another set of stamps.[19]

Family

His son, Charles Gould, was notable as a geological surveyor.

See also

- All pages with titles containing Gouldi for species named for Gould

- All pages with titles containing Gouldii for species named for Gould

Bibliography

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: John Gould |

- John Gould; Birds of Europe; 1832–37. 5 vols. Drawn from nature & on stone by J. & E. Gould. Printed by Hullmandel

- John Gould; A monograph of the Ramphastidae, or family of toucans; 1833–35. 1 vol. 34 plates; Artists: J. Gould, E. Gould, E. Lear and G. Scharf; Lithographers: E. Gould and E. Lear;

- John Gould; A synopsis of the birds of Australia, and the adjacent islands; 1837–38 1 vol. 73 plates; Artist and lithographer: E. Gould

- John Gould; The birds of Australia; 1840–48. 7 vols. 600 plates; Artists: J. Gould and E. Gould; Lithographer: E. Gould

- John Gould; A monograph of the Odontophorinae, or partridges of America; 1844–50 1 vol. 32 plates; Artists: J. Gould and H. C. Richter; Lithographer: H. C. Richter

- John Gould; The birds of Asia; 1850–83 7 vols. 530 plates, Artists: J. Gould, H. C. Richter, W. Hart and J. Wolf; Lithographers: H. C. Richter and W. Hart; Parts 33–55 completed after Gould's death by R. Bowdler Sharpe; Vol VI :Artist and lithographer: W. Hart

- John Gould; The birds of Australia; Supplement 1851–69. 1 vol. 81 plates; Artists: J. Gould and H. C. Richter; Lithographer: H. C. Richter

- John Gould; The Birds of Great Britain; 1862–73. 5 vols. 367 plates; Artists: J. Gould, J. Wolf, H.C. Richter and W. Hart; Lithographers: H. C. Richter and W. Hart

- John Gould; The birds of New Guinea and the adjacent Papuan Islands, including many new species recently discovered in Australia; 1875–88. 5 vols. 300 plates; Parts 13–25 completed after Gould's death by R. Bowdler Sharpe; Artists: J. Gould and W. Hart; Lithographer: W. Hart

- John Gould; A monograph of the Trochilidae, or family of humming-birds Supplement, completed after Gould's death by R. Bowdler Sharpe; 1880–87. 5 parts. 58 plates; Artists: J. Gould and W. Hart; Lithographer: W. Hart

Notes

John Gould also happened to live next to the famous Broad Street pump during 1854. The pioneering epidemiologist John Snow mentions Gould and his assistant Prince in his famous On the mode of communication of cholera.[20]

References

- 1 2 Waterhouse, F H (1885). The dates of publication of some of the Zoological Works of the late John Gould. R H Porter, London.

- ↑ Russell, Roslyn (2011). The business of nature : John Gould and Australia. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Stephens, M. (2005). "Patterns of Nature: The Art of John Gould at the National Library" (PDF). National Library of Australia News. 15 (7): 7–10.

- ↑ Cayley, N. (1938). "John Gould as an Illustrator". Emu. 38 (2): 167–172. doi:10.1071/MU938167.

- ↑ Sauer, G C. "Forty years association with John Gould the Bird Man". Archives of natural history. 1: 159–166. doi:10.3366/anh.1985.013.

- ↑ Sulloway, F J (1982). "The Beagle collections of Darwin's finches (Geospizinae)" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History (Zoology). 43 (2): 49–94.

- ↑ Sulloway, F J (1982). "Darwin and his finches: the evolution of a legend" (PDF). Journal of the History of Biology. 15: 1–53. doi:10.1007/BF00132004.

- ↑ Biography – Charles Coxen – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Yarrundi was a property on Dart Brook near Scone, New South Wales.

- ↑ "Mammals of Australia, key plates [picture]". Digital collections. National Library of Australia. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ McEvey, Allan (1968). "Collections of John Gould Manuscripts and Drawings". The La Trobe Journal. 1 (2): 17–31.

- ↑ Anon (1885). "A guide to the Gould collection of Humming-birds" (4 ed.). British Museum (Natural history).

- 1 2 http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/specialcollections/virtualexhibitions/birdsbeesandblooms/birds/johngouldthebirdsofgreatbritain/

- ↑ http://www.sotherans.co.uk/Prints/gould/britain.php

- ↑ Sotherans: Gould prints: Britain

- ↑ The Ruling Passion of John Gould. London: 1991

- ↑ http://www.peterharrington.co.uk/store/category/illustrated/

- ↑ Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M. (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Gould", p. 104).

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael (2003). Whose Bird? Men and Women Commemorated in the Common Names of Birds. London: Christopher Helm. p. 146.

- ↑ Anon (2009). "Migrating waterbirds: international postage paid envelopes and aerogrammes" (PDF). Stamp bulletin. 300: 14.

- ↑ Snow J. On the mode of communication of cholera. 2011:1–217.

Sources

- Chisholm, A. H. 1938. Out of the past: Gould material discovered. Victoria Naturalist 55:95–102.

- Gould, John. 1840–1848. The Birds of Australia: in seven volumes.

- Maguire, T. H. 1846–1852.Portraits of the Honorary Members of the Ipswich Museum (George Ransome, Ipswich).

-

Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney, eds. (1890). "Gould, John". Dictionary of National Biography. 22. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 287–8.

Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney, eds. (1890). "Gould, John". Dictionary of National Biography. 22. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 287–8. - Sauer, G. C. 1948. Bird art and artists; John Gould. American Antiques Journal 3:6–9.

- Sauer, G. C. 1983. John Gould in America. In Contributions to the History of North American Natural History. London, Society for the Bibliography of Natural History Special Publication No. 2:51–58.

- Desmond, Adrian and James Moore. 1991. Charles Darwin (Penguin)

- Sauer, G. C. 1982. John Gould the bird man: a chronology and bibliography. (Melbourne, Landsdowne)

- Tree, Isabella. 1991. The Ruling Passion of John Gould (Grove Weidefeld)

- Tree, Isabella. 2003. The Bird Man – The Extraordinary Story of John Gould (Ebury Press)

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Gould, John". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Gould. |

- John Gould at Find a Grave

- Exhibition at the Australian Museum

- The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle – bibliography by Freeman, R. B. (1977)

- A. H. Chisholm, 'Gould, John (1804–1881)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, MUP, 1966, pp 465–467.

- Scanned books from Gallica

- The Mammals of Australia – Series of high resolution images taken from the 1845 edition.

- Digitised works by John Gould (1804–1881) at Biodiversity Heritage Library