John Baskerville

| John Baskerville | |

|---|---|

|

Baskerville in later life, oil on canvas by James Millar. | |

| Born |

28 January 1706 Wolverley, England |

| Died |

8 January 1775 (age 68) Easy Hill, Birmingham, England |

| Monuments | Industry and Genius |

| Occupation | Manufacturer, printer and type designer |

John Baskerville (28 January 1706 – 8 January 1775) was an English businessman, in areas including japanning and papier-mâché, but he is best remembered as a printer and type designer.[1]

Life

Baskerville was born in the village of Wolverley, near Kidderminster in Worcestershire and was a printer in Birmingham, England. He was a member of the Royal Society of Arts, and an associate of some of the members of the Lunar Society. He directed his punchcutter, John Handy, in the design of many typefaces of broadly similar appearance. In 1757, Baskerville published a remarkable quarto edition of Virgil on wove paper, using his own type. It took three years to complete, but it made such an impact that he was appointed printer to the University of Cambridge the following year.[2]

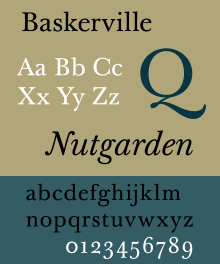

John Baskerville printed works for the University of Cambridge in 1758 and, although an atheist,[3] printed a splendid folio Bible in 1763. His typefaces were greatly admired by Benjamin Franklin, a printer and fellow member of the Royal Society of Arts, who took the designs back to the newly created United States, where they were adopted for most federal government publishing. Baskerville's work was criticised by jealous competitors and soon fell out of favour, but since the 1920s many new fonts have been released by Linotype, Monotype, and other type foundries – revivals of his work and mostly called 'Baskerville'. Emigre released a popular revival of this typeface in 1996 called Mrs Eaves, named for Baskerville's wife, Sarah Eaves.[4] Baskerville's most notable typeface Baskerville represents the peak of transitional type face and bridges the gap between Old Style and Modern type design.[5]

Baskerville also was responsible for significant innovations in printing, paper and ink production. He developed a technique which produced a smoother whiter paper which showcased his strong black type. Baskerville also pioneered a completely new style of typography adding wide margins and leading between each line.[6]

Death and interments

Baskerville died in January 1775 at his home, Easy Hill. He requested that his body be placed

in a Conical Building in my own premises Hearetofore used as a mill which I have lately Raised Higher and painted and in a vault which I have prepared for It. This Doubtless to many may appear a Whim perhaps It is so—But it is a whim for many years Resolve'd upon, as I have a Hearty Contempt for all Superstition the Farce of a Consecrated Ground the Irish Barbarism of Sure and Certain Hopes &c I also consider Revelation as it is call'd Exclusive of the Scraps of Morality casually Intermixt with It to be the most Impudent Abuse of Common Sense which Ever was Invented to Befool Mankind.[1]

However, in 1821 a canal was built through the land and his body was placed on show by the landowner until Baskerville's family and friends arranged to have it moved to the crypt of Christ Church, Birmingham. Christ Church was demolished in 1897 so his remains were then moved, with other bodies from the crypt, to consecrated catacombs at Warstone Lane Cemetery.[3] In 1963 a petition was presented to Bimingham City Council requesting that he be reburied in unconsecrated ground according to his wishes.[7]

Baskerville House was built on the grounds of Easy Hill.

Commemoration

A Portland stone sculpture of the Baskerville typeface, Industry and Genius, in his honour stands in front of Baskerville House in Centenary Square, Birmingham. It was created by local artist David Patten.[8]

Gallery

Some examples of volumes published by Baskerville.

John Milton's Paradise Lost (1758)

John Milton's Paradise Lost (1758) Volume One of The works of Joseph Addison (1761)

Volume One of The works of Joseph Addison (1761) Title page of Baskerville's 1763 Bible

Title page of Baskerville's 1763 Bible- The 1766 translation of Virgil into English, by Robert Andrews

See also

References

- Citations

- 1 2 Mosley, James (2004). "Baskerville, John (1706–1775)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 17 Nov 2014.

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn. (2011). Books: A living history. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications. pp. 111

- 1 2 "Printer's Reburial Demanded". The Times. March 9, 1963. p. 6.

- ↑ "Baskerville revisited". Print. 50: 28D. 1996.

- ↑ Meggs, Philip B., Purvis, Alston W. "Graphic Design and the Industrial Revolution" History of Graphic Design. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2006. p.122.

- ↑ Sutton, James; Sutton, Alan (1988). An Atlas of Typeforms. Wordsworth Editions. p. 59. ISBN 1-85326-911-5.

- ↑ "Petition Presented For Printer's Reburial". The Times. 13 Mar 1963. p. 5.

- ↑ "Industry and Genius". Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- Bibliography

- Benton, Josiah Henry (1914). John Baskerville: Type-founder and Printer, 1706–1775. Boston: The Merrymount Press.

- Gaskell, Philip (1973). John Baskerville: A Bibliography. Paul P. B. Minet. ISBN 0-85609-029-8.

- Pardoe, Frank Ernest (1975). John Baskerville of Birmingham Letter-Founder and Printer. London: Frederick Muller, Ltd.

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Baskerville, John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Baskerville, John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Birmingham City Council page on Industry and Genius (includes picture)

- Revolutionary Players website

- Baskerville the Animated Movie

- Some typographical studies on the use of the Baskerville font (in French).

_by_James_Millar.jpeg)