Jim Crow economy

| Part of a series on |

| Economic, applied, and development anthropology |

|---|

|

Provisioning systems |

|

Case studies

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

The term Jim Crow economy applies to a specific set of economic conditions during the period when the Jim Crow laws were in effect; however, it should also be taken as an attempt to disentangle the economic ramifications from the politico-legal ramifications of "separate but equal" de jure segregation, to consider how the economic impacts might have persisted beyond the politico-legal ramifications.

It includes the intentional effects of the laws themselves, effects that were not explicitly written into laws, and effects that continued after the laws had been repealed. Some of these impacts continue into the present. The primary differences of the Jim Crow economy, compared to a situation like apartheid, revolve around the alleged equality of access, especially in regard to land ownership and entry into the competitive labor market; however, those two categories often relate to ancillary effects in all other aspects of life.

Introduction

During the decade following the Civil War, the freed slaves made gains in political participation, land ownership, and personal wealth; but, those gains were somewhat temporary, perhaps because the mood of the federal policy-makers changed from punishing secessionists, to repatriating them. In the decades following the closure of the Freedmen's Bureau, in the South, black political participation was curtailed, the potential for acquiring new land was diminished, and ultimately Plessy v. Ferguson would usher in the Jim Crow era.

By the end of the first decade of the 20th century, not only was African American progress halted, it was regressing. Leading up to and following World War I, the agrarian economy of the South was in dire straits, beginning a slow shift to urbanization and limited industrialization; this period also saw the beginning of the Great Migration. The 1930s saw increasing urbanization and industrialization in the South; and, federal policies of the time, such as the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act, attempted to force economic parity between the South and the rest of the nation (Wright 1987:171).

By the time of the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the scientific racism that had underlain much of the justification for the Jim Crow era legal racism had been discredited, the South had substantially closed its wealth gap with the rest of the nation, and America was both urbanized and industrialized. However, the African American struggle to earn economic parity, that had made progress during the first half century of the postbellum era, had largely been reversed during the second half. Legally, equality was assured, but that did little to actually promulgate equal conditions in daily life.

Some of the gains in the South's economic relation to the rest of the U.S. can be explained by population shifts to other regions; so, it may have had as much to do with spreading poverty around, as spreading wealth around. In the period when agriculture had formed the basis of the economy, land and labor were intimately tied together in the ownership of farmland; in the shift to urban industrialization, neither land tenure, nor labor opportunities were necessarily improved for African Americans. Thus, to understand the Jim Crow economy it is required to look to the social and political climate prior to the implementation of the laws, and to the economic inertia that continued to impact people's lives after the repeal of the laws.

Usage

Frequently sources will mention the Jim Crow economy, and then proceed to discuss only what is specific to the topic being broached by a particular author; however, unlike the laws passed to restrict access to services and education, the laws that governed the economy were often written in race-neutral terms, with inequality stemming from enforcement decisions. The economic impacts of Jim Crow are also intertwined with changes in the overall economy of the United States, from the Civil War through the 20th century. There is a temporal rhythm to the economic impacts of Jim Crow; from the Reconstruction onward, social trends preceded policy changes that, in turn, preceded economic changes.

Just in the last decade, "the Jim Crow economy" has been mentioned in the context of 19th century taxi drivers (Ortiz 2006), mid-20th century urban industrialization (Godwin 2000), post-World War II domestic service (Kusmer & Trotter 2009), and even in regard to Lumbee Indians in North Carolina (Lowery 2010). Clearly, it is a topic that covers a great deal of breadth; but, in dealing with only particular topics, there is always the risk of losing sight of the issue as a whole. Moreover, there is the risk of applying it to any economic topic in the Jim Crow era, making the phrase meaningless.

Land

In the decades following the Civil War, there were steady increases in African American ownership of farmland in the South, from 3 million acres (12,000 km2) in 1875, to 8 million acres (32,000 km2) in 1890, 12 million acres (49,000 km2) at the turn of the century, and peaking at 12,800,000 acres (52,000 km2) in 1910 (Reynolds 2002:4). Other estimates suggest that total black ownership of land in the South may have been as much as 15 million acres (61,000 km2) within a half century after emancipation (Mitchell 2000:507). There were also setbacks, due to property being taken illegally; in the first 30 years of the 20th century, 24,000 acres (97 km2) were taken, from 406 separate landowners (Darity Jr. & Frank 2003:327). By 1930, the number of black owned farms was 3% lower than what it had been at the turn of the century (Woodman 1997:22).

Rural

After being freed, there were 2 main ways for African Americans to acquire land in the South: either buy it from a private landowner, or stake a claim to public land offered by the federal government under laws like the Southern Homestead Act of 1866, and by state governments, such as South Carolina's Land Commission. The Southern Homestead Act opened up the transfer of public land in the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi, with the hope of providing land to freedmen by limiting the claims to 80 acres (320,000 m2) for the first 2 years (Pope 1970:203).

The results were less purchasers than had been hoped for, largely because the recently freed slaves did not have the material means to settle unimproved property, and only 4,000 of the 11, 633 total claims were registered by freedmen (Pope 1970:205). Within the South, the Southern Homestead Act was seen as further punishment of attempting to secede; this was substantiated, by the repeal of 1876, when old enmities gave way to the promise of federal revenues (Gates 1940:311). After the Act was repealed, cash sales of public lands were reopened to large-scale purchasers; the repeal was reversed in 1888, but prior to that point more than 5,500,000 acres (22,000 km2) of land in the 5 public land states of the South were sold off to land speculators and timber harvesters (Gates 1936:667).

South Carolina's Land Commission was a unique case of a Reconstruction-era state government organization that was formed explicitly for the purpose of selling bonds to fund the purchase of non-operating plantations and selling the land to small farm operators over a 10-year repayment schedule at 7% annual interest (Bethel 1997:20). From 1868-1879, the Land Commission sold farmland to 14,000 African American families (Bethel 1997:27). Another well documented sample of African American property ownership in a non-public land state comes from census and tax records in Georgia. In the year following the end of the Civil War, black property owners accumulated approximately 10,000 acres (40 km2) of land, with a value of about $22,500; however, on average, African Americans in Georgia held a total wealth of less than $1 per person (Higgs 1982:728). Between 1880-1910, Georgia's African Americans increased their average wealth, from $8 per person to $26.59, with some setbacks occurring around the turn of the century; however, relative to white Georgians, that amounted to an increase from 2% to 6% of total wealth held (Higgs 1982:729).

By expanding the defined territory of the South to 16 states (including Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia), in 1910, there were 175,000 black farm owners compared to 1.15 million white farm owners (Higgs 1973:150). Discounting the states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Oklahoma, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia, the average white-owned farm was nearly twice the size of the average black-owned farm (Higgs 1973:162).

Land ownership was an important source of capital for both groups, but the ability to use the land with maximal productivity was not equally afforded to both groups. From the antebellum period up to the mid-1880s, all land owners were highly dependent on credit from merchant transporters of cotton; however, as the transportation infrastructure improved the white land owners were able to use their greater land holdings to attract credit directly from Northern financiers, and were thus able to usurp the position of the merchant transporters that furnished necessary staple goods to cotton growers (Woodman 1977:547).

Drawing from a representative sample of 4,695 farms in 27 counties in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina, regarding the 1879-1880 cotton crop, white owners were able to leave more than 4 times the amount of land fallow, had nearly twice the value in farming implements, and were more than a third more likely to have access to fertilizer than were the black land owners (Ransom & Sutch 1973:141). Thus, African Americans were laboring harder for lower crop returns, and putting the long-term productivity of their land in greater jeopardy (Ransom & Sutch 1973:142).

Between 1900-1930, in the South, 4.7% of black farm owners became tenant farmers; while 9.5% of white farmers were reduced from owners to tenants during that period, that amounted to only 46.6% of all white farmers being tenants compared to 79.3% of all black farmers (Woodman 1997:9). Moreover, there were fewer opportunities to acquire land, as white owners refused to sell land to black purchasers regardless of the price being offered, and there was little legal recourse when property was lost due to extra-legal practices (Higgs 1973:165). In any case, the availability of funds was greatly reduced by the failure of government-initiated lending institutions like the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company; and, lending organizations founded by benevolent societies often found themselves too overextended to withstand moderate levels of default on loans, such as the failure of the True Reformers Savings Banks in 1910 (Heen 2009:386).

Lending organizations outside the South, backed by Northern capitalists, were mostly unwilling to make loans supporting African American land purchase, out of concern that the development of a class of black landowners would result in increased demands from Northern industrial workers (Ezeani 1977:106). With new land being unobtainable, and existing land only able to be subdivided so far before becoming unusable as farmland, the progeny of the land owning generation were pressured to move to Southern cities, or outside the South completely (Bethel 1997:98;101). When the U.S. Became involved with World War I, Northern cities became the focus of out-migration, and Northern industry became the employer of many former farmers (Tolnay et al.:991). The South was much slower to industrialize; and, where predominantly white land owners retained large tracts of farmland, and where the population of black laborers remained high, agriculture continued as the economic base (Roscigno & Tomaskovic-Devey 1996:576).

Urban

African American movement into urban centers had begun just after the end of the Civil War; and, by 1870, the black population, in cities greater than 4,000, was increased by 80%, compared to only a 13% increase in the white population (Kellogg 1977:312). In contrast to the antebellum urban settlement pattern, cities that rose to prominence in the postbellum years tended to be more highly segregated (Groves & Muller 1975:174). To provide an example of monetary value, in Georgia, African American holdings of urban property increase from a value of $1.2 million in 1880 to $8.8 million in 1910, even though the properties were often in the least desirable locations; however, at the end of World War I, much of that property was sold off to white buyers, as African Americans started moving to Northern cities in large numbers (Higgs 1982:730-731).

There were no explicit racial zoning ordinances in Southern cities prior to 1910; however, the individuals who developed and sold real estate in these areas often refused to sell to African American purchasers, outside of the prescribed areas (Kellogg 1982:41). In fact, the National Association of Realtors could take disciplinary action against a realtor for selling property to a person of a different race than those who presently lived in a particular neighborhood (Herrington et al.:163-164). The impact was greatest on those who migrated to cities early on; for those who migrated to the North, after 1965, there is evidence that they moved into neighborhoods that were the lease segregated by race (Tolnay et al.:999).

The initial pattern, starting in the 19th century, was to allow the original enclave neighborhoods to become overcrowded, while individual property owners subdivided acreages in low-lying areas at the urban periphery or close to industrial areas that employed unskilled laborers (Groves & Muller 1975:170). Starting with Baltimore in 1910, a number of cities throughout the South starting implementing racial zoning codes; although these were overturned by the Buchanan v. Warley Supreme Court decision, in 1917, many large and small cities simply changed from overtly racial zoning to instituting zoning based on existing neighborhood composition (Silver 1997). In Alabama, “Birmingham continued illegally to enforce a racial zoning code until 1951” (Silver 1997:38).

Many growing cities and towns enacted their own Jim Crow ordinances; and, as they grew, they planned low-cost housing in areas with less access to public services, often using transportation corridors and natural features as buffer zones (Lee 1992:376-377). This practice was not restricted to the South; for example, in 1940s Detroit, a 6 ft (1.8 m). high concrete wall was erected to divide the Eight Mile-Wyoming area from neighboring white developments (Hayden 2003:111-112). These policies did not just impact the poor and undereducated; for example, around 1950, a cooperative housing development, that housed mainly faculty from Stanford University, limited availability to non-whites to 10%, in order to preserve financing for mortgages (Arrow 1998:92).

Labor

Demographics

The first consideration in the availability of labor is the overall distribution of the African American population. In 1870, 85.3% of all African Americans lived in the South, by 1910 that number dropped to 82.8%, by 1950 the number had dwindled to 61.5%, and by 1990 it was down to 46.2% living in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, or Virginia (Shelley & Webster 1998:168).

In 1900, African Americans represented 34.3% of the South's overall population, in 1910 they still comprised 31.6% of the population; however, by 1950, they were only 22.5% of the total population, and that number dropped to 21% in 1960 (Nicholls 1964:35). Within the South, the African American urban population went from 8.8% in 1870 to 19.7% in 1910, while the white urban population went from 7.7% to 19.5% in that same time period; however, in 1920, 25.4% of whites and 23.5% of blacks were in urban areas, a slight change in the pace of urbanization that only occurred in the South (Roback 1984:1190). For the United States, as a whole, the African American population went from 79% rural in 1910, to 85% urban in 1980 (Aiken 1985:383).

From 1870-1880, the relative rates of out-migration for whites and blacks were fairly similar; however, in the decade from 1880-1890 black out-migration slowed relative to whites in Alabama (42.3%), Mississippi (17.8%), and Tennessee (72%), and in the decade from 1890-1900 the same relative decline began in Arkansas (9.3%), Georgia (45%), and Kentucky (73.9%), in total numbers (Roback 1984:1188-1189). In the decade of World War I both groups were leaving the South, with whites leaving at a slightly higher rate; but in the decade of World War II, the South lost 1.58 million blacks, and only 866,000 whites (Wright 1987:174).

In the decade from 1950–1960, the net out-migration was 1.2 million blacks, to only 234,000 whites; but, from 1960-1970 the picture changed dramatically, still losing 1.38 million blacks, but gaining 1.8 million whites. Starting in the decade of 1970-1980, there was a net influx of both groups, but with a markedly higher rate for whites, at 3.56 million to only 206,000. The raw numbers mask that the median education level of African Americans migrating out of the South was 6.6 years, up to 1960; whereas, by that same time, slightly more than a third of the white males in the South, with more than 5 years of college, had been born outside that region (Wright 1987:173). Thus, another factor that is masked by the raw numbers is that the areas African Americans were moving into were already experiencing black unemployment rates of up to 40%, and where there were few employers that utilized unskilled and undereducated labor, at all (Wright 1987:175).

Rural Labor

The second consideration is how laws governing contract enforcement, enticement, emigrant agents, vagrancy, convict leasing, and debt peonage function to immobilize labor and restrict competition in a system where agriculture was the dominant consumer of labor. The South was overwhelmingly based on agricultural production through the postbellum years, only seeing substantial increases in industrial manufacturing starting in the 1930s; and, for those who did not own farmland, the dominant forms of employment were: farm laborer, sharecropper, share-renter, and fixed renter. Throughout this period there were some large landholders that used a set wage for farm laborers; however, the general lack of banks in the South made this arrangement problematic (Parker 1980:1024-1025).

Using a set wage for laborers without contracts presented the problem of either overpaying during periods when labor demands were low, or risking the loss of the laborer during the peak of harvest season (Roback 1984:1172). Thus, the dominant pattern was to contract labor for an entire season which, when combined with the lack of liquid capital, favored the development of sharecroppers who received a share of the profits from the sale of the crops at the end of the season, or share-renters who paid a share of their crops as rent at the end of the season (Parker 1980:1028-1030).

Whether white or black, the wage earned by the tenant farmer was relatively equal (Higgs 1973:151). Moreover, the tenant and the planter class landowner shared in the inherent risks of uncertain crop production; thus, external capital was invested in the merchant transporter who furnished staple goods in return, rather than in the agriculturalists directly (Parker 1980:1035). By the last decade of the 19th century, the planter class had recovered from the Civil War enough to both keep Northern industrialist manufacturing interests out of the South, and to take the role of merchant themselves (Woodman 1977:546).

As the planter class came back to prominence, the rural and urban middle class lost power, and the poor rural tenant farmers were set in opposition based both on race, and the inherent superiority of the wealthy landowner (Nicholls 1964:25). It was in this social climate that the Jim Crow laws began to appear, amidst the Populist challenges of the tenant farmers of both races; thus, the laws may be seen as a tactic to drive a wedge between the members of the lowest social class, by using obvious physical traits to define the opposing sides (Roscigno & Tomaskovic-Devey 1996:568).

Labor Laws

Outside of laws that specifically addressed the issue of race, other laws that impacted the tenant farmer were often differentially enforced, to the detriment of African Americans. Enticement laws, and emigrant agent laws were geared toward immobilizing labor by preventing other employers from trying to lure employees away with promises of better wages; in the case of enticement the laws limited competition between landowners to the beginning of each contract season, and the emigrant agent laws created limitations on employers trying to lure out of the region altogether (Roback 1984:1166-1167;1169).

Contract enforcement laws were contingent on demonstration of an intent to defraud the contractor, but often failure to live up to the terms of the contract were treated as intentional; these laws were addressed in the Supreme Court decision of Bailey v. Alabama. Vagrancy laws functioned to keep workers from exiting the labor force entirely, and were often used to forcibly ensure that every able body was engaged in some form of work; in some cases, African Americans were made into misdemeanants, through vagrancy laws, just on the basis of traveling outside the territory where they were personally known (Roback 1984:1168). In any case, African Americans were often disadvantaged in obtaining work contracts outside the areas where they were personally known, due to employers not wanting to pay the cost of having to check on their claims of specific knowledge or skills germane to a task (Ransom & Sutch 1973:139).

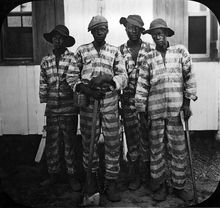

Under convict leasing, those who were convicted of a crime had their labor sold to employers by the prison system; in this case, the control over the prisoner was transferred to the employer, who had little concern for the well-being of the convict beyond the term of the lease (Roback 1984:1170). Ordinary debt peonage could affect any farmer working under the crop lien system, whether due to crop failure or merchant monopoly; however, the criminal-surety system functioned in a similar way, as the worker had little control over determining when their debt was to be considered repaid (Roback 1984:1174-1176).

Urban Labor

The third consideration is how the overall transition from an agriculture-based economy to an urban, industrial economy. In the South, industrial growth started with labor-intensive, unskilled industries; for example, manufacturing employment increased from 14.5% in 1930 to 21.3% in 1960, but the increase was largest for non-durable goods (Nicholls 1964:26-27). For black males, in the South, agricultural employment dropped from 43.6% in 1940, to 4.9% in 1980; in that same time period, manufacturing employment rose from 14.2%, to 26.9% (Heckman & Payner 1989:148). There was also more pressure for African American women to work outside the home, often for low wages in the domestic service sector; for example, in the late 1930s, female domestics earned $3–8 per week, sometimes a bit less in the South (Thernstrom & Thernstrom 1999:35).

For black females, throughout the South, manufacturing employment rose from 3.5% in 1940, to 17.2% in 1980; for that same time period, personal service employment decreased from 65.8%, to 13.7% (Heckman & Payner 1989:1989). One study, looking at non-agricultural employment from 1920–1930, determined that black males were losing jobs not to industrial mechanization, but to white males (Anderson & Halcoussis 1996:12).

During the civil rights era, “economic coercion” was used to prevent participation, by denying credit, causing evictions, and canceling insurance policies (Bobo & Smith 1998:208). In 1973, only 2.25% of 5 million U.S. businesses were owned by African Americans; furthermore, 95% of those businesses employed fewer than 9 people, and two-thirds generated gross annual receipts of less than $50,000 (Bailey 1973:53). In the most extreme analysis, the level of urban residential segregation, along the unidirectional economic dependency of African American communities, presents the possibility that they may be treated as a “national collectivity of internal colonies” (Bailey 1973:61).

From this perspective, small black-owned businesses are seen as the “ghetto domestic sector,” white-owned businesses that operate within the internal colonies are seen as the “ghetto enclave sector,” and the black laborers that work outside the community are seen as the “ghetto labor-export sector” (Bailey 1973:62). The idea of a black internal colony makes it especially notable that the Jim Crow era was brought to a close not only by the internal influences of the civil rights movement, but also from external pressures brought by international trading partners and decolonized developing nations (Cable & Mix 2003:198).

Life & Death

One of the major sources of wealth transfer is inheritance (Darity Jr. & Nicholson 2005:81). Race-based life insurance rates began in the early 1880s, and included higher rates, reduced benefits, and no commission for the insurance agent on policies written for African Americans. When state laws were passed to prevent race-based differential insurance rates, companies simply stopped selling insurance to black clients in those states (Heen 2009:369). When customers that had existing policies tried to purchase additional coverage from their local agent, at times when the company had stopped soliciting policies in that area, they were told they could travel to a regional office to make their purchase (Heen 2009:390-391).

From 1896, scientific racism was used as the basis for declaring black clients as substandard risks, which also affected the ability of black-owned insurance companies to secure capital to provide their own policies (Heen 2009:387). By 1970, the black-owned insurance companies that had remained in business found themselves targeted for take over by white insurance companies that hoped to increase their number of black employees by acquiring smaller companies (Heen 2009:389). In the first decade of the 21st century, major insurance companies like Metropolitan Life, Prudential, American General, and John Hancock Life were still settling court cases brought by policy holders that had purchased their policies during the Jim Crow era (Heen 2009:360-361).

Another economic impact of death is seen when the deceased does not have a will, and land is bequeathed to multiple people, under intestacy law, as tenancies in common (Mitchell 2000:507-508). Frequently, the recipients of such property do not realize that if one of the common owners wishes to sell their share, then the entire estate can be put up for partition sale. Most state statutes suggest that partition in kind be preferred over partition sale, except where properties cannot be divided equitably for the parties involved; however, many courts opt to require properties be put up for partition sale because the monetary value of the land is higher as a single parcel than a number of subdivided parcels, and also, to some extent, because the utility value of rural land is higher if it can be used a single productive unit (Mitchell 2000:514-515;563).

This means that a land developer can purchase one person's share of a tenancy in common, and then use their position to force a partition sale of the entire property. Thus, a person who has inherited a common share of a property that they do not personally use, might be inclined to sell their share thinking that they are only selling the rights to a portion of the property, and wind up initiating the displacement of other inheritors that are actually living on the property. African American estate planning is thought to be minimal in rural, economically depressed areas, and developers are known to target properties in those areas (Mitchell 2000:517).

Legacy

An economic analysis, conducted at the end of the 1970s, concluded that even if the freed slaves had been given the 40 acres and a mule that had been promised by the Freedman's Bureau, it still would not have been enough to entirely close the wealth gap between whites and blacks, to that point in time (DeCanio 1979:202-203). In 1984, the median wealth for black households was $3,000, compared to $39,000 for white households (Bobo & Smith 1998:188). By 1993, the median wealth for black households was $4,418, compared to $45,740 for white households (Darity Jr. & Nicholson 2005:79). The research that underlies public program policy decisions continues to be guided by sensationalistic “failure studies” that focus on communities as liabilities, rather than identifying positive community aspects that programs could build upon as assets (Woodson 1989:1028;1039).

African American residential centralization, that started in the postbellum and Great Migration periods, continues to negatively impact employment rates (Herrington et al.:169). In fact, “one third of African Americans live in areas so intensely segregated that they are almost completely isolated from other groups in society” (Mitchell 2000:535). The unemployment effects of residential centralization are twice as problematic in metropolitan areas with total populations over 1 million (Weinberg 2000:116). A one standard deviation reduction in residential centralization could reduce unemployment by about a fifth; and, a complete elimination of residential centralization could reduce unemployment by almost half for high school educated males, and nearly two-thirds for college educated males and females (Weinberg 2000:126).

Counting owners and tenants, there were 925,708 black farmers in 1920; in 2000, there were about 18,000 black farmers, which is roughly 11,000 less than the number of black farm owners in 1870 (Mitchell 2000:527-528). As the recent decision of Pigford v. Glickman has shown, there are still race-based biases in way government entities like the United States Department of Agriculture decide how to disburse farm credit. By federal regulation, the local commissions that make the decisions must be elected from current farm owners; in two cases unrelated to the Pigford decision, five different county commissioners were found to have wrongly denied disaster assistance to African American farmers (Mitchell 2000:528-529). Additionally, black farmers trying to obtain credit to purchase farmland being lost by black owners “experienced delays” while funding was being extended to white borrowers (Reynolds 2002:16).

References

Aiken, C.S., (1985). New settlement pattern of rural blacks in the American South. Geographical Review, 75(4), 383–404.

Arrow, K.J., (1998). What has economics to say about racial discrimination? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(2), 91–100.

Anderson, G.M. & Halcoussis, D., (1996). The political economy of legal segregation: Jim Crow and racial employment patterns. Economics & Politics, 8(1), 1–15.

Bailey, R., (1973). Economic aspects of the black internal colony. The Review of Black Political Economy, 3(4), 43–72.

Bethel, E.R., (1997). Promiseland, a century of life in a Negro community, Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Bobo, L.D. & Smith, R.A., (1998). From Jim Crow racism to laissez-faire racism. In W. F. Katkin, N. Landsman, & A. Tyree, eds. Beyond pluralism: The conception of groups and group identities in America. pp. 182–220.

Cable, S. & Mix, T.L., (2003). Economic Imperatives and Race Relations: The Rise and Fall of the American Apartheid System. Journal of Black Studies, 34(2), 183.

Darity Jr, W. & Frank, D., (2003). The economics of reparations. American Economic Review, 93(2), 326–329.

Darity Jr, W. & Nicholson, M.J., (2005). Racial wealth inequality and the Black family. In African American family life: ecological and cultural diversity. New York, NY: Guilford Press, pp. 78–85.

DeCanio, S.J., (1979). Accumulation and discrimination in the postbellum South. Explorations in Economic History, 16(2), 182–206.

Ezeani, E.C., (1977). Economic conditions of freed black slaves in the United States, 1870–1920. The Review of Black Political Economy, 8(1), 104–118.

Gates, P.W., (1940). Federal Land Policy in the South 1866-1888. The Journal of Southern History, 6(3), 303–330.

Gates, P.W., (1936). The Homestead Law in an Incongruous Land System. The American Historical Review, 41(4), 652–681.

Godwin, J.L., (2000). Black Wilmington and the North Carolina Way: Portrait of a Community in the Era of Civil Rights Protest, Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Groves, P.A. & Muller, E.K., (1975). The evolution of black residential areas in late nineteenth-century cities. Journal of Historical Geography, 1(2), 169–191.

Hayden, D., (2003). Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000, New York, NY: Vintage Books/Random House.

Heckman, J.J. & Payner, B.S., (1989). Determining the impact of federal antidiscrimination policy on the economic status of blacks: a study of South Carolina. The American Economic Review, 79(1) 138–177.

Heen, M.L., (2009). Ending Jim Crow Life Insurance Rates. Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy, 4(2), 360.

Herrington, B., Erber, E. & Clay, P.L., (1977). Black urban settlement patterns: Trends and prospects. Habitat International, 2(1/2), 157–172.

Higgs, R., (1982). Accumulation of property by Southern blacks before World War I. The American Economic Review, 72(4), 725–737.

Higgs, R., (1973). Race, tenure, and resource allocation in southern agriculture, 1910. The Journal of Economic History, 33(1), 149–169.

Kellogg, J., (1977). Negro urban clusters in the postbellum South. Geographical Review, 67(3), 310–321.

Kellogg, J., (1982). The formation of black residential areas in Lexington, Kentucky, 1865-1887. The Journal of Southern History, 48(1), 21–52.

Kusmer, K.L. & Trotter, J.W., (2009). African American Urban History Since World War II, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lee, D., (1992). Black Districts in Southeastern Florida. Geographical Review, 82(4), 375–387.

Lowery, M.M., (2010). Lumbee Indians in the Jim Crow South: Race, Identity, and the Making of a Nation, Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press.

Mitchell, T.W., (2000). From Reconstruction to Deconstruction: Undermining Black Landownership, Political Independence, and Community Through Partition Sales of Tenancies in Common. Nw. UL Rev., 95, 505.

Nicholls, W.H., (1964). The South as a Developing Area. The Journal of Politics, 26(1), 22–40.

Ortiz, P., (2006). Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing and White Violence in Florida from Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920, Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Parker, W.N., (1980). The South in the national economy, 1865-1970. Southern Economic Journal, 46(4), 1019–1048.

Pope, C.F., (1970). Southern homesteads for Negroes. Agricultural History, 44(2), 201–212.

Ransom, R.L. & Sutch, R., (1973). The Ex-Slave in the Post-Bellum South: A Study of the Economic Impact of Racism in a Market Environment. The Journal of Economic History, 33(1), 131–148.

Reynolds, B.J., (2002). Black farmers in America, 1865-2000: the pursuit of independent farming and the role of cooperatives., Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture. Rural Business Cooperative Service.

Roback, J., (1984). Southern Labor Law in the Jim Crow Era: Exploitative or Competitive. U. Chi. L. Rev., 51, 1161.

Roscigno, V.J. & Tomaskovic-Devey, D., (1996). Racial economic subordination and white gain in the US South. American Sociological Review, 61(4), 565–589.

Silver, C., (1997). The racial origins of zoning in American cities. In Urban Planning and the African American Community. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication, Inc., pp. 23–42.

Thernstrom, S. & Thernstrom, A., (1999). America in black and white: One nation, indivisible, New York, NY: Touchstone Books.

Tolnay, S.E., Crowder, K.D. & Adelman, R.M., (2000). " Narrow and Filthy Alleys of the City"?: The residential settlement patterns of black southern migrants to the North. Social Forces, 78(3) 989–1015.

Weinberg, B.A., (2000). Black residential centralization and the spatial mismatch hypothesis. Journal of Urban Economics, 48(1), 110–134.

Woodman, H.D., (1997). Class, Race, Politics, and the Modernization of the Postbellum South. The Journal of Southern History, 63(1), 3–22.

Woodman, H.D., (1977). Sequel to slavery: The new history views the postbellum South. The Journal of Southern History, 43(4), 523–554.

Woodson, R.L., (1989). Race and Economic Opportunity. Vand. L. Rev., 42, 1017-1047.

Wright, G., (1987). The economic revolution in the American South. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 1(1), 161–178.