Kiautschou Bay concession

| Kiautschou Bay | ||||||||||||

| 膠州灣 | ||||||||||||

| German Leased Territory | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

Kiautschou Bay concession | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Tsingtau | |||||||||||

| Languages |

| |||||||||||

| Political structure | Leased Territory | |||||||||||

| Head of State | Kaiser Wilhelm II | |||||||||||

| Historical era | German colonization in the Pacific Ocean | |||||||||||

| • | Colonization | 6 March 1898 | ||||||||||

| • | Japanese Occupation | 7 November 1914 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Goldmark | |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Kiautschou Bay concession | |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 膠州灣 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 胶州湾 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| German name | |||||||||||

| German | Kiautschou-Bucht | ||||||||||

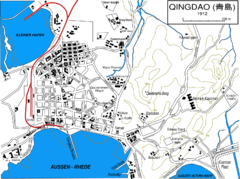

The Kiautschou Bay concession was a German leased territory in Imperial China which existed from 1898 to 1914. Covering an area of 552 km2 (213 sq mi), it was located around Jiaozhou Bay on the southern coast of the Shandong Peninsula (German: Schantung-Halbinsel). Jiaozhou was romanized as Kiaochow, Kiauchau or Kiao-Chau in English and as Kiautschou or Kiaochau in German. The administrative center was at Tsingtau (Pinyin Qingdao).

Background of German expansion in China

Germany was a relative latecomer to the imperialistic scramble for colonies across the globe, a German colony in China was envisioned as a two-fold enterprise: as a coaling station to support a global naval presence, and because it was felt that a German colonial empire would support the economy in the mother country. Densely populated China came into view as a potential market, with thinkers such as Max Weber demanding an active colonial policy from the government. In particular the opening of China was made a high priority, because it was thought to be the most important non-European market in the world.

However, a global policy (Weltpolitik) without global military influence appeared impracticable, so, assessing Britain's great strength came from its navy, the Germans began to build one too. This fleet was supposed to serve German interests during peace through gunboat diplomacy, and in times of war, through commerce raiding, to protect German trade routes and disrupt hostile ones. Imitating Britain, a network of global naval bases was a key requirement for this intention.

Again intending to directly copy Britain, the acquisition of a harbor in China was from the start intended to be a model colony: all installations, the administration, the surrounding infrastructure and the utilization was to show the Chinese, the German nation and other colonial powers an effective colonial policy.

German acquisition of the territory

In 1860, a Prussian expeditionary fleet arrived in Asia and explored the region around Jiaozhou Bay. The following year the Prussian-Chinese Treaty of Peking was signed.[1] After journeys to China between 1868 and 1871, the geographer Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen recommended the Bay of Jiaozhou as a possible naval base. In 1896 Rear Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, at that time commander of the East Asian Cruiser Division, examined the area personally as well as three additional sites in China for the establishment of a naval base. Rear Admiral Otto von Diederichs replaced Tirpitz in East Asia and focused on Jiaozhou Bay even though the Berlin admiralty had not formally decided on a base location.

On 1 November 1897, the Big Sword Society brutally murdered two German Roman Catholic priests of the Steyler Mission in Juye County in southern Shandong. This event was known as the "Juye Incident." Admiral von Diederichs, commander of the cruiser squadron, wired on 7 November 1897 to the admiralty: "May incidents be exploited in pursuit of further goals?"[2] Upon receipt of the Diederichs cable, chancellor Chlodwig von Hohenlohe counseled caution, preferring a diplomatic resolution. However, Kaiser Wilhelm II intervened and the admiralty sent a message for Diederichs to "proceed immediately to Kiautschou with entire squadron ..." to which the admiral replied "will proceed ... with greatest energy."[3]

Diederichs at that moment only had his division’s flagship SMS Kaiser and the light cruiser SMS Prinzess Wilhelm available at anchor at Shanghai, the corvette Arcona was laid up for repairs and the light cruiser Irene in a dockyard at Hong Kong for an engine refit. The shallow draft small cruiser SMS Cormoran, operating independent of the cruiser division, was patrolling the Yangtze. Diederichs weighed anchor, ordered Prinzess Wilhelm to follow next day and Cormoran to catch up at sea. The three ships arrived off Tsingtao after dawn on 13 November 1897 but made no aggressive moves. With his staff and the three captains of his ships aboard, Diederichs landed with his admirals tender at Tsingtao’s long pier to reconnoiter. He determined that his landing force would be vastly outnumbered by Chinese troops, but he had qualitative superiority.[4]

At 0600, Sunday, 14 November 1897, Cormoran steamed into the inner harbor to provide inshore fire support, if necessary.[5] Kaiser and Prinzess Wilhelm cleared boats to carry an amphibious force of 717 officers, petty officers and sailors armed with rifles.[6] Diederichs on horseback and his column marched toward the Chinese main garrison and artillery battery, a special unit swiftly disabled the Chinese telegraph line and others occupied the outer forts and powder magazines. With speed and effectiveness, Diederichs’ actions had achieved their primary objective by 0815.[7]

Signalmen restored the telegraph line and the first messages were received and deciphered. Diederichs was stunned to learn that his orders had been canceled and he was to suspend operations at Kiautschou pending negotiations with the Chinese government. If he had already occupied the village of Tsingtao, he was to consider his presence temporary. He responded, thinking the politicians in Berlin had lost their nerve to political or diplomatic complications: "Proclamation already published. ... Revocation not possible." After considerable time and uncertainty, the admiralty finally cabled congratulations and the proclamation to remain in effect; Wilhelm II promoted him to vice admiral.[8]

Admiral von Diederichs consolidated his positions at Kiautschou Bay. The admiralty dispatched the protected cruiser SMS Kaiserin Augusta from the Mediterranean to Tsingtao to further strengthen the naval presence in East Asia.[9] On 26 January 1898 the marines of III. Seebataillon arrived on the liner Darmstadt. Kiautschou Bay was now secure.[10]

Negotiations with the Chinese government began and on 6 March 1898 the German Empire retreated from outright cession of the area and accepted a leasehold of the bay for 99 years, or until 1997 (as the British did in Hong Kong's New Territories). One month later the Reichstag ratified the treaty on 8 April 1898. Kiautschou Bay was officially placed under German protection by imperial decree on 27 April and Kapitän zur See [captain] Carl Rosendahl was appointed governor. These events ended Admiral von Diederichs' responsibility (but not his interest) in Kiautschou; he wrote that he had "fulfilled [his] purpose in the navy."[11]

As a result of the lease treaty, the Chinese government gave up the exercise of its sovereign rights within the leased territory of approximately 83,000 inhabitants (to which the city of Jiaozhou did not belong), as well as in a 50 km wide neutral zone ("neutrales Gebiet"). According to international law, the leased territory ("territoire à bail") remained legally part of China but for the duration of the lease, all sovereign powers were to be exercised by Germany.

Moreover, the treaty included rights for construction of railway lines and mining of local coal deposits. Many parts of Shandong outside of the German leased territory came under German influence. Although the lease treaty set limits to the German expansion, it became a starting point for the following cessions of Port Arthur to Russia, of Weihaiwei to Great Britain and Kwang-Chou-Wan to France.

Organization and development of the leased territory

Due to the fact that the territory was not strictly speaking a colony, and because of the importance which the leased territory had for the German navy, it was not placed under the supervision of the imperial colonial office (Reichskolonialamt) but under that of the imperial naval office (the Reichsmarineamt or RMA).

At the top of the territory stood the governor (all five office holders were senior navy officers), who was directly subordinated to the secretary of state of the RMA, Alfred von Tirpitz. The governor was head of the military and the civil administration within the colony. The former was run by the chief of staff and deputy governor, the latter by the Zivilkommissar [civil commissioner]. Further important functionaries of Kiautschou were the official for the construction of the harbor, and after 1900 the chief justice and the 'Commissioner for Chinese Affairs.' The Gouvernementsrat [government council of the territory] and after 1902 the 'Chinese Committee' acted as organs of advice for the governor. The departments of finance, construction, education and medical services were directly subordinated to the governor, because these were crucial with regard to the idea of a model colony.

.jpg)

Kiautschou was transformed into a modern realm with Germany investing upwards of $100 million.[12] The impoverished fishing village of Tsingtau was laid out with wide streets, solid housing areas, government buildings, electrification throughout, a sewer system and a safe drinking water supply, a rarity in large parts of Asia at that time and later. The area had the highest schools density and highest per capita student enrollment in all of China, with primary, secondary and vocational schools funded by the Berlin treasury and Protestant and Roman Catholic missions.[13]

With the expansion of economic activity and public works, German banks opened branch offices, the Deutsch-Asiatische Bank being the most prominent. The completion of the Shantung Railroad in 1910 provided a connection to the Trans-Siberian Railway and thus allowed travel by train from Tsingtau to Berlin.[14]

After the Chinese revolution of 1911 ran its course, many wealthy Chinese and politically connected ex-officials settled in the colony because of the safe and orderly environment it offered. Sun Yat-sen visited the Tsingtau area and stated in 1912, “... I am impressed. The city is a true model for China’s future.”[15]

Governors of Kiautschou Bay concession

All Governors of Kiautschou Bay concession were naval officers with the rank of Kapitän zur See [captain].

| Carl Rosendahl | 7 March 1898 – 19 February 1899 |

| Carl Otto Ferdinand Paul Jaeschke | 19 February 1899 – 27 January 1901 (died in office) |

| Max Rollmann | 27 January 1901 – 8 June 1901 (acting) |

| Oskar von Truppel | 8 June 1901 – 19 August 1911 |

| Alfred Meyer-Waldeck | 19 August 1911 – 7 November 1914 |

Later history

On 15 August 1914, at the outbreak of World War I in Europe, Japan delivered an ultimatum to Germany demanding that it relinquishes its control of the disputed territory of Kiaoutschou.[16] Upon rejection of the ultimatum, Japan declared war on 23 August and the same day its navy bombarded the German territory. On 7 November 1914, the bay was occupied by Japanese forces (see Siege of Tsingtao). The occupied territory was returned to China on 10 December 1922 but the Japanese again occupied the area from 1937 to 1945 during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

See also

%2C_Hafen.jpg)

- China–Germany relations

- German colonial empire

- Eulenburg Expedition

- Jiaozhou Governor's Hall, located in Qingdao.

- Tsingtao beer, Germany's enduring legacy to Chinese brewing

- Tsingtauer Neueste Nachrichten

Notes

- ↑ Gottschall, By Order of the Kaiser, p. 134; the treaty, signed September 1861, allowed Prussian warships to operate in Chinese waters for the protection of German trade and missionaries and promised swift retribution for crimes committed against German nationals by Chinese perpetrators

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 156

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 157

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 160

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 166

- ↑ After German unification, Prussian Army Lt. Gen. Albrecht von Stosch was appointed in 1872 the first chief of the imperial admiralty. He had no naval experience but brought significant administrative talent to his post – and he understood the power that emanated from “the tip of an army bayonet”. Stosch removed the small contingents of marines from the warships and instead trained the seamen of cruisers in the use of small arms, infantry tactics and amphibious landings [Gottschall, p. 42].

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 161

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 163

- ↑ SMS Kaiserin Augusta became the flagship of a second cruiser division with SMS Deutschland and SMS Gefion and Cormoran; the two 4-ship divisions would form the 8-ship squadron

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 176

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 177

- ↑ Toyokichi Iyenaga (Oct 26, 1914). "What is Kiaochou worth?". The Independent. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ↑ Schultz-Naumann, Joachim (1985). Unter Kaisers Flagge: Deutschlands Schutzgebiete im Pazifik und in China einst und heute (in German). Universitas. p. 183. ISBN 978-3-8004-1094-1.

- ↑ Schultz-Naumann, p. 182

- ↑ Schultz-Naumann, p. 184

- ↑ Duffy, Michael (22 August 2009). "Primary Documents - Count Okuma on the Japanese Capture of Tsingtao, 15 August 1914". firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

Bibliography

- Gottschall, Terrell D. By Order of the Kaiser, Otto von Diederichs and the Rise of the Imperial German Navy 1865–1902. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. 2003. ISBN 1-55750-309-5

- Schultz-Naumann, Joachim. Unter Kaisers Flagge, Deutschlands Schutzgebiete im Pazifik und in China einst und heute [Under the Kaiser’s Flag, Germany’s Protectorates in the Pacific and in China then and today]. Munich: Universitas Verlag. 1985.

- Schrecker, John E. Imperialism and Chinese Nationalism; Germany in Shantung. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1971.

- Steinmetz, George. The Devils' Handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa, and Southwest Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

External links

- German colonies (in German)

- WorldStatesmen

Coordinates: 36°07′24″N 120°14′44″E / 36.12333°N 120.24556°E