Jharokha Darshan

Jharokha Darshan was a daily practice of addressing the public audience (darshan) at the balcony (jharokha) at the forts and palaces of medieval kings in India. It was an essential and direct way of communicating face-to-face with the public, and was a practice which was adopted by the Mughal emperors.[1] The balcony appearance in the name of Jharokha Darshan also spelled jharokha-i darshan was adopted by the 16th-century Mughal Emperor Akbar,[2][3][4] even though it was contrary to Islamic injunctions.[5] Earlier, Akbar's father Emperor Humayun had also adopted this Hindu practice of appearing before his subjects at the jharokha to hear their public grievances.[2]

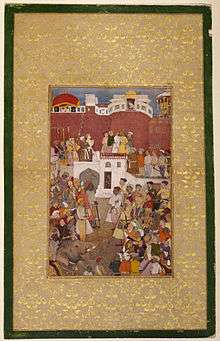

Darshan is a Sanskrit word which means "sight" and "beholding" (also means: "the viewing of an idol or a saint"[6]) which was adopted by Mughals for their daily appearance before their subjects. This also showed a Hindu influence,[7][8] It was first practiced by Humayun before Akbar adopted it as a practice at sunrise.[9][2] Jharokha is an easterly facing "ornate bay-window", canopied, throne-balcony, the "balcony for viewing" (an oriel window projecting out of the wall[10]) provided in every palace or fort where the kings or emperors resided during their reign. Its architecture served not only the basic need for lighting and ventilation but also attained a divine concept during the reign of Mughals. The jharokha appearances by the Mughals have been depicted by many paintings.[8]

Giving Jharokha Darshan from this jharokha was a daily feature. This tradition was also continued by rulers who followed Akbar (r. 1556–1605 CE). Jahangir (r. 1605–27 CE) and Shah Jahan (r. 1628–58 CE) also appeared before their subjects punctiliously. However, this ancient practice was discontinued by Aurangzeb during his 11th year of reign as he considered it a non-Islamic practice, a form of idol worship.[9] In Agra Fort and Red Fort, the jharokha faces the Yamuna and the emperor would stand alone on the jharokha to greet his subjects.[11]

Mughal emperors during their visits outside their capital used to give Jharokha Darshan from their portable wooden house known as Do-Ashiayana Manzil.

During the Delhi Durbar held in Delhi on 12 December 1911, King George V and his consort, Queen Mary, made a grand appearance at the jharokha of the Red Fort to give a "darshan" to 500,000 common people.[12]

Practices by various rulers

During Humayun's reign

The Hindu practice of appearing before the people at the jharokha was started by Humayun, though the practice is generally credited to Akbar. Humayun had fixed a drum beneath the wall so that the petitioners assembled below the jharokha could beat it to draw his attention.[2]

During Akbar's reign

Akbar's daily practice of worshiping the sun in the early morning at his residence in Agra Fort led him to initiate the Jharokha Darshan. Hindus, who used to bathe in the river at that hour greeted Akbar when he appeared on the jharokha window for sun worship. It was also the period when Akbar was promoting his liberal religious policy, and in pursuance of this liberal approach he started the Jharokha Darshan.[13] Thereafter, Akbar would religiously start his morning with prayers and then attend the Jharokha Darshan and greet the large audience gathered every day below the jharokha. He would spend about an hour at the jharokha "seeking acceptance of imperial authority as part of popular faith", and after this he would attend the court at the Diwan-i-Aam for two hours attending to administrative duties.[14]

The crowd of people assembled below the balcony generally consisted of soldiers, merchants, craft persons, peasants, and women and sick children.[15] As the balcony was set high, the king would stand on a platform so that people gathered below could reassure themselves that he was alive and that the empire was stable; even when the sovereign was ill. He felt that it was necessary to see them publicly at least once a day in order to maintain his control, and guard against immediate anarchy. It also had a symbolic purpose. During this time people might make personal requests directly to Akbar, or present him with petitions for some cause. Akbar, therefore, began appearing at the jharokha twice a day and would hear the complaints of the people who wished to speak to him.[2][16] Sometimes, while the emperor gave his Jharokha Darshan, he would let out a thread down the jharokha so that people could tie their complaints and petitions seeking his attention and justice.[17] It was an effective way of communication and information exchange process, which Badauni, a contemporary of Akbar noted Jharokha Darshan worked effectively under Akbar who spent about four and half hours regularly in such darshan.[18] Akbar's paintings giving Jharokha Darshan are also popular.[4]

During Jahangir's reign

Akbar's son, Emperor Jahangir, also continued the practice of Jharokha Darshan. In Agra Fort, the jharokha window is part of the structure which represents the Shah Burj, the Royal Tower. The tower is in the shape of an octagon and has a white marble pavilion. During Jahangir's time and even more frequently under Shah Jahan's rule this jharokha was used for giving darshan.[8][19] During Jahangir's Jharokha Darshan, hanging a string to tie petitions, was also practiced. This was also a Persian system under naushrwan. Jahangir elaborated on this system by adopting a golden chain to tie the petitions but Aurangzeb stopped it.[20] Nur Jahan, Jahangir's wife, was also known to have sat for the Jharokha Darshan and conducted administrative duty with the common people and hearing their pleas.[21] Jahangir was fully dedicated to the practice and made it a point to conduct the Jharokha Darshan even if he was sick; he had said "even in the time of weakness I have gone every day to the jharokha, though in great pain and sorrow, according to my fixed custom."[9]

Jahangir's painting giving Jharokha Darshan shows him sitting at the jharokha in a side profile, bedecked with jewelry and wearing a red turban in the background of a pale purple coloured cushion.[8]

During Shah Jahan's reign

-2.jpg)

Emperor Shah Jahan maintained a rigorous schedule during his entire thirty years rule and used to get up at 4 AM and, after ablutions and prayers, religiously appeared at the jharokha window to show himself to his subjects. During his stay in Agra or Delhi, huge crowds used to assemble to receive his darshan below the balcony. He would appear before the public 45 minutes after sunrise. His subjects would bow before him which he would reciprocate with his imperial salute. There was one particular group of people known as darshaniyas (akin to the guilds of Augustales of the Roman Empire) who were "servile" to the king and who would take their food only after they had a look at the face of the emperor which they considered as auspicious. More than half an hour had to be spent by the King at the balcony as it was the only time people could submit petitions to the king directly through the chain let down for the purpose (which was drawn up by attendants) of receiving such petitions by passing the nobles of the court.[6] At one time in 1657 when Shah Jahan was sick he could not appear for the Jharokha Darshan which spread speculations of his death.[8]

There were times when people used to gather below the jharokha window to hold protest demonstrations to place their grievances before the emperor. One such incident occurred in 1641 in Lahore when people who were affected by famine and were starving pleaded before Shah Jahan to provide famine relief.[9]

It is also said of Shah Jehan that his Islamic orthodoxy was more than that of his father or his grandfather and that he was skeptical to carry out the function of Jharokha Darshan as it could be misconstrued as worship of the sun. However, this practice was so deep-rooted with in the "Mughal Kingship and State" that he was compelled to continue this practice.[22]

During Aurangzeb's reign

There is a proof that Aurangzeb continued the Mughal practice of Jharokha Darshan in a painting dated 1710 in which he is shown at the jharokha with two noblemen in attendance in the foreground. In this painting, the emperor is painted in a side profile and has a white jama (upper garment) attire adorned with a turban in a background of blue colour.[8] In 1670, Hindus had assembled at the jharokha to protest against the jizya tax imposed on them by Aurangzeb.[9] However, Aurangzeb who was a "puritanical" and practiced strict Islamic codes of conduct in his personal life, stopped this practice on the basis that it was idolization of human beings.[23] [24] He stopped this practice during the 11th year of his rule.[7] He also felt that it was "savouring of the Hindu ceremony of darshan".[25]

Do-Ashiayana Manzil

Do-Ashiayana Manzil was a portable wooden house used by the Mughal emperors during their visits outside their capital. This was a double storied house built with a platform supported over 16 pillars, of 6 yards height. Pillars were 4 cubits in height joined with nuts and bolts which formed the upper floor. This functioned as a sleeping quarter for the king and also for worship and holding Jharokha Darshan,[19] and considered it an emulation of Hindu practice.[26]

Delhi Durbar

On the occasion of the Delhi Durbar that was held on 12 December 1911, King George V and his consort, Queen Mary, made a grand appearance at the jharokha of the Red Fort to give a "darshan" to 500,000 common people who had assembled there to greet them.[12]

References

- ↑ Reddi 2001, p. 81.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wade 1998, p. 12.

- ↑ Together with History. p. 97. ISBN 8181370740.

- 1 2 "Frames with a rich history". The Tribune. 21 March 2015.

- ↑ & Goswami, p. 72.

- 1 2 Hansen 1986, p. 102.

- 1 2 Gopal 1994, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kaur, Manpreet (February 2015). "Romancing The Jharokha: From Being A Source Of Ventilation And Light To The Divine Conception" (pdf). International Journal of Informative & Futuristic Research.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Eraly 2007, p. 44.

- ↑ Liddle 2011, p. 289.

- ↑ Fanshawe 1998, p. 33.

- 1 2 "Delhi, what a capital idea!". Hindustan Times. 19 November 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ Congress 1998, p. 247.

- ↑ Rai, Raghunath (2010). Themes in Indian History. FK Publications. p. 141. ISBN 9788189611620.

- ↑ History of India. Saraswati House Pvt Ltd. pp. 150–. ISBN 978-81-7335-498-4. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ Mohammada 2007, p. 310.

- ↑ Aggarwal 2002, p. 207.

- ↑ Reddi 2014, p. 72.

- 1 2 Nath 2005, p. 192.

- ↑ Grover 1992, p. 215.

- ↑ Mukherjee 2001, p. 140.

- ↑ Indica. Heras Institute of Indian History and Culture, St. Xavier's College. 2003.

- ↑ Gandhi 2007, p. 648.

- ↑ A Text Book of Social Sciences. Pitambar Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-81-209-1467-4.

- ↑ The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. pp. 420–. GGKEY:S0CL29JETWX.

- ↑ Mehta 1986, p. 493.

Bibliography

- Aggarwal, Devi Dayal (1 January 2002). Jurisprudence in India: Through the Ages. Gyan Books. ISBN 978-81-7835-108-7.

- Congress, Indian History (1998). Proceedings – Indian History Congress. Indian History Congress.

- Eraly, Abraham (1 January 2007). The Mughal World: Life in India's Last Golden Age. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-310262-5.

- Fanshawe, H.C. (1998). Delhi: Past and Present. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1318-8. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- Gandhi, Surjit Singh (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold: 1606-1708 C.E. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0858-5.

- Gopal, Ram (1 January 1994). Hindu Culture During and After Muslim Rule: Survival and Subsequent Challenges. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-85880-26-6.

- Goswami, Ed. Anuj. Diamond History Quiz Book. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. ISBN 978-81-7182-641-4.

- Grover, Verinder (1992). West Asia and India's Foreign Policy. Deep & Deep Publications. ISBN 978-81-7100-343-3.

- Hansen, Waldemar (1 January 1986). The Peacock Throne: The Drama of Mogul India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0225-4.

- Liddle, Swapna (2011). Delhi 14 : Historic walks. Westland. ISBN 978-93-81626-24-5.

- Mehta, Jl (1986). Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-207-1015-3.

- Mohammada, Malika (1 January 2007). The Foundations of the Composite Culture in India. Aakar Books. ISBN 978-81-89833-18-3.

- Mukherjee, Soma (2001). Royal Mughal Ladies and Their Contributions. Gyan Books. ISBN 978-81-212-0760-7.

- Nath, Ram (2005). Private Life of the Mughals of India: 1526 – 1803 A.D. Rupa & Company. ISBN 978-81-291-0465-6.

- Mukherjee, Soma (2001). Royal Mughal Ladies and Their Contributions. Gyan Books. ISBN 978-81-212-0760-7.

- Reddi, C. V. Narasimha (January 2001). Public information management: ancient India to modern India, 1500 B.C.-2000 A.D. Himalaya Pub. House.

- Reddi, C.V. Narasimha (1 January 2014). EFFECTIVE PUBLIC RELATIONS AND MEDIA STRATEGY. PHI Learning. ISBN 978-81-203-4871-4.

- Wade, Bonnie C. (20 July 1998). Imaging Sound: An Ethnomusicological Study of Music, Art, and Culture in Mughal India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-86840-0.