Jewel bearing

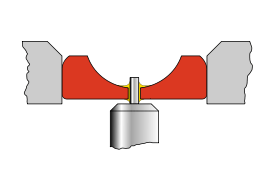

A jewel bearing is a plain bearing in which a metal spindle turns in a jewel-lined pivot hole. The hole is typically shaped like a torus and is slightly larger than the shaft diameter. The jewel material is usually some form of synthetic corundum, such as ruby. Jewel bearings are used in precision instruments where low friction, long life, and dimensional accuracy are important, but their largest use is in mechanical watches.

History

Jewel bearings were invented in 1704 for use in watches by Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, Peter Debaufre, and Jacob Debaufre, who received an English patent for the idea. Originally natural jewels were used, such as diamond, sapphire, ruby, and garnet. In 1902, a process to make synthetic sapphire and ruby (crystalline aluminium oxide, also known as corundum) was invented by Auguste Verneuil, making jewelled bearings much cheaper. Today most jewelled bearings are synthetic ruby or sapphire.

Historically, jewel pivots were made by grinding using diamond abrasive. Modern jewel pivots are often made using high-powered lasers, chemical etching, and ultrasonic milling.

Characteristics

The advantages of jewel bearings include high accuracy, very small size and weight, low and predictable friction, good temperature stability, and the ability to operate without lubrication and in corrosive environments. They are known for their low kinetic friction and highly consistent static friction.[1] The static coefficient of friction of brass-on-steel is 0.35, while that of sapphire-on-steel is 0.10–0.15.[1][2] Sapphire surfaces are very hard and durable, with Mohs hardness of 9 and Knoop hardness of 1800,[3] and can maintain smoothness over decades of use, thus reducing friction variability.[1] Disadvantages include brittleness and fragility, limited availability/applicability in medium and large bearing sizes and capacities, and friction variations if the load is not axial.

Uses

The predominant use of jewel bearings is in mechanical watches, where their low and predictable friction improves watch accuracy as well as improving bearing life. Manufacturers listed the number of jewels prominently on the watch face or back, as an advertising point. A typical fully jeweled time-only watch has 17 jewels: two cap jewels, two pivot jewels, an impulse jewel for the balance wheel, two pivot jewels, two pallet jewels for the pallet fork, and two pivot jewels each for the escape, fourth, third, and center wheels. In modern quartz watches, the timekeeper is a quartz crystal in an electronic circuit, so accuracy of timekeeping is not dependent on low friction of the mechanical parts and jewels are not often used.

The other major use of jeweled bearings is in sensitive measuring instruments. They are typically used for delicate linkages that must carry very small forces, in instruments such as galvanometers, compasses, gyroscopes, gimbals, and turbine flow meters. Bearing bores are typically smaller than 1 mm and support loads weighing less than 1 gram, although they are made as large as 10 mm and may support loads up to about 500 g.[1]

See also

References

- Baillie, G. H. (1947). Watchmakers And Clockmakers Of The World (2e ed.). Nag Press.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Baillio, Paul. "Jewel bearings solve light load problems" (PDF). Bird Precision. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Hahn, Ed (January 31, 2000). "Coefficients of friction for various horological materials". TZ Classic Forum. TimeZone.com. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ↑ "Synthetic Ruby and O-Rings". Retrieved 2013-06-01.

External links

- Paul Baillio, "Jewel Bearings Solve Light Load Problems" (PDF)

- A. C. Lawson, "Design Factors for Jewel Bearing Systems" (PDF)

- R. H. Warring, "Calculating Frictional Losses in Jewel Bearing Movements" (PDF)

- American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute

- TimeZone.com discussion of watch jeweling

- Monochrome-watches, What are jewel bearings, Xavier Markl