Jessie Redmon Fauset

| Jessie Redmon Fauset | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

April 27, 1882 Fredericksville, Camden County, New Jersey |

| Died |

April 30, 1961 (aged 79) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

Jessie Redmon Fauset (April 27, 1882 – April 30, 1961) was an American editor, poet, essayist, novelist, and educator.[1] Before and after working on The Crisis, she worked for decades as a French teacher in public schools in Washington, DC and New York City. In her early career, she traveled to Paris in the summer and studied at La Sorbonne.

After contributing numerous columns, Fauset became the literary editor of the NAACP magazine The Crisis, serving 1919 to 1926, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance. During this period, she encouraged many younger, new writers. She also was the editor and co-author of the African-American children's magazine The Brownies' Book. She considered W. E. B. Du Bois, who hired her and whose work she studied, to be her mentor. She published four novels during the 1920s and 1930s, exploring the lives of the black middle-class. She was considered to be one of the most intelligent women novelists of the Harlem Renaissance, and earned the nickname "the midwife," for helping younger writers. In her lifetime she also wrote essays, poetry and short fiction.[2]

Life and work

She was born Jessie Redmon Fauset on April 27, 1882, in Fredericksville, Camden County, New Jersey.[3] She was the seventh child of Redmon Fauset, an African Methodist Episcopal minister, and Annie (née Seamon) Fauset. Jessie's mother died when she was young, and her father remarried. He had three children with his second wife Bella, a white Jewish woman who converted to Christianity. Bella brought three children to the family from her first marriage. Both parents emphasized education for their children.

Fauset came from a large family mired in poverty. Her father died when she was young; two of her half-siblings were still under the age of five. She attended the Philadelphia High School for Girls, the city's top academic school. She graduated as valedictorian of her class and likely the school's first African-American graduate.[4] She wanted to study at Bryn Mawr College, but they circumvented the issue of admitting a black student by finding her a scholarship for another university.

She continued her education at Cornell University in upstate New York, graduating in 1905 with a degree in classical languages.[5] She was the first black woman accepted to the Phi Beta Kappa Society.[4] Fauset later received her master's degree in French from the University of Pennsylvania.

Following college, Fauset became a teacher at Dunbar High School (then named as M Street High School), the academic high school for black students in Washington, DC, which had a segregated public school system. She taught French and Latin,[3] and went to Paris for the summers to study at la Sorbonne.

In 1919 Fauset left teaching to become the literary editor for the The Crisis, founded by W.E.B. Du Bois of the NAACP. She served in that position until 1926. Fauset became a member of the NAACP and represented them in the Pan African Congress in 1921. After her Congress speech, the Delta Sigma Theta sorority made her an honorary member.

In 1927, Fauset left The Crisis and returned to teaching, this time at DeWitt Clinton High School in New York City, where she may have taught a young James Baldwin.[6] She taught in New York City public schools until 1944.

In 1929, when she was 47, Fauset married for the first time, to insurance broker Herbert Harris. They moved from New York City to Montclair, New Jersey, where they led a quieter life.[6] Harris died in 1958. She moved back to Philadelphia with her step-brother, one of Bella's children. Fauset died on April 30, 1961, from heart disease.

Literary editor at The Crisis

Jessie Fauset's time with The Crisis is considered the most prolific literary period of the magazine's run. In July 1918, Fauset became a contributor to The Crisis, sending articles for the "Looking Glass" column from her home in Philadelphia. By the next July, managing editor W. E. B. Du Bois requested she move to New York to become the full-time Literary Editor. By October, she was installed in the Crisis office, where she quickly took over most organizational duties.

As Literary Editor, Fauset fostered the careers of many of the most well-known authors of the Harlem Renaissance, including Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, Nella Larsen, Georgia Douglas Johnson, Anne Spencer, George Schuyler, Arna Bontemps, and Langston Hughes. Fauset was the first person to publish Hughes. As editor of The Brownies' Book, the children's magazine of The Crisis, she had included a few of his early poems. In his memoir The Big Sea, Hughes wrote, "Jessie Fauset at The Crisis, Charles Johnson at Opportunity, and Alain Locke in Washington were the people who midwifed the so-called New Negro Literature into being."[4]

Beyond nurturing the careers of other African-American modernist writers, Fauset was also a prolific contributor to both The Crisis and The Brownies' Book. During her time with The Crisis, she contributed poems and short stories, as well as a novella, translations from the French of writings by black authors from Europe and Africa, and a multitude of editorials. She also published accounts of her extensive travels. Notably, Fauset included five essays, including "Dark Algiers the White," detailing her six-month journey with Laura Wheeler Waring to France and Algeria in 1925 and 1926.

After eight years serving as Literary Editor, Fauset found that conflicts between her and Du Bois were taking their toll. In February 1927, she resigned her position. She was listed as a "Contributing Editor" the next month.

After leaving the magazine, Fauset concentrated on writing novels, while supporting herself through teaching. From 1927 to 1944, she taught French at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, while continuing to publish novels.

Novels

Between 1924 and 1933, Fauset published four novels: There is Confusion (1924), Plum Bun (1928), The Chinaberry Tree (1931), and Comedy, American Style (1933). She believed that T. S. Stribling's novel Birthright, written by a white man about black life, could not fully portray her people. Fauset thought there was a dearth of positive depictions of African-American lives in contemporary literature. She was inspired to portray African-American life both as realistically, and as positively, as possible, and wrote about the middle-class life she knew of an educated person. At the same time, she worked to explore contemporary issues of identity among African Americans, including issues related to the community's assessment of skin color. Many were of mixed race with some European ancestry.

The Great Migration resulted in many African Americans moving to industrial cities; in some cases, individuals used this change as freedom to try on new identities. Some used partial European ancestry and appearance to pass as white, for temporary convenience or advantage: for instance, to get better service in a store or restaurant, or to gain a job. Others entered white society nearly permanently to take advantage of economic and social opportunities, sometimes leaving darker-skinned relatives behind. This issue was explored by other writers of the Harlem Renaissance in addition to Fauset, who was herself light-skinned and visibly of mixed race. Vashti Crutcher Lewis, in an essay "entitled 'Mulatto Hegemony in the Novels of Jessie Redmon Fauset,' suggests that Fauset's novels illustrate the evidence of a color hierarchy with lighter-skinned blacks enjoying more privilege."[7]

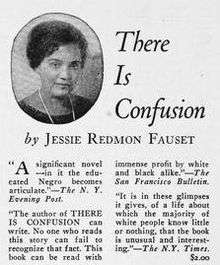

- There is Confusion was praised widely upon release, including by The New York Times and Alain Locke in The Crisis. He wrote, "“[H]ere in refreshing contrast with the bulk of fiction about the Negro, we have a novel of the educated and aspiring classes.”[8] This novel traces the family histories of Joanna Mitchell and Peter Bye, who must each come to terms with their complex racial histories.

- Plum Bun has warranted the most critical attention. It explores the theme of "passing". The mixed-race protagonist, Angela Murray, who has partial European ancestry, passes for white in order to gain some advantages. In the course of the novel, she eventually reclaims her African-American identity.

- The Chinaberry Tree has not received much critical attention. Set in New Jersey, this novel explores the longing for "respectability" among the contemporary African-American middle class. The protagonist Laurentine seeks to overcome her "bad blood" through marriage to a "decent" man. Ultimately, Laurentine must redefine "respectable" as she finds her own sense of identity.

- Comedy, American Style, Fauset's last novel, explores the destructive power of "color mania"[5] among African Americans, some of whom discriminated within the black community on the basis of skin color. The protagonist's mother Olivia brings about the downfall of the other characters due to her own such internalized racism.

Selected works

Novels

- There Is Confusion (1924) (ISBN 1-55553-066-4)

- Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral (1928) (a further study of the passing phenomenon; ISBN 0-8070-0919-9)

- The Chinaberry Tree: A Novel of American Life (1931) (ISBN 1-55553-207-1)

- Comedy, American Style (1933)

Poems

- "Rondeau." The Crisis. April 1912: 252.

- "La Vie C'est La Vie." The Crisis. July 1922: 124.

- "'Courage!' He Said." The Crisis. November 1929: 378

Short stories

- "Emmy." The Crisis. December 1912: 79-87; January 1913: 134-142.

- "My House and a Glimpse of My Life Therein." The Crisis. July 1914: 143-145.

- "Double Trouble." The Crisis. August 1923: 155-159; September 1923: 205-209.

Essays

- "Impressions of the Second Pan-African Congress." The Crisis. November 1921: 12-18.

- "What Europe Thought of the Pan-African Congress." The Crisis. December 1921: 60-69.

- "The Gift of Laughter." In Locke, Alaine. The New Negro: An Interpretation. New York: A. and C. Boni, 1925.

- "Dark Algiers the White." The Crisis. 1925–26 (vol. 29–30): 255–258, 16–22.

References

- ↑ Paul, Ruben. "Jessie Redmon Faucet". in American Literature- A Research and Reference Guide. Retrieved Sep 20, 2011.

- ↑ Gale. "Jessie Redmon Fauset" (PDF). Harlem Renaissance: A Gale Critical Companion. Retrieved Sep 20, 2011.

- 1 2 "Fauset, Jessie R. (1882-1961)". The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- 1 2 3 West, Kathryn (2004). "Fauset, Jessie Redmon". In Wintz, Cary D.; Finkelman, Paul. Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Routledge.

- 1 2 Carolyn Wedin Sylvander, Jessie Redmon Fauset, Black American Writer.

- 1 2 Zafar, Rafia, ed. (2011). Harlem Renaissance: Five Novels of the 1920s. Library of America. p. 850.

- ↑ [Lewis, Vashti Crutcher. "Mulatto Hegemony in the Novels of Jessie Redmon Fauset"] The Harlem Renaissance: A Gale Critical Companion, v2. Detroit: Gale, 2003, p. 376

- ↑ Alain Locke, "Review: There Is Confusion", The Crisis, February 1924

Further reading

- Laurie Champion,American Woman Writers, 1900-1945: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook.

- Kevin De Ornellas, Writing African American Women: An Encyclopedia of Literature by and about Women of Color (Greenwood Press, 2006), edited by Elizabeth Ann Beaulieu.

- Joseph J. Feeny, "Jessie Fauset of The Crisis: Novelist, Feminist, Centenarian" (1983).

- Henry Louis Gates Jr, Nellie McKay, The Norton Anthology of African American Literature (2004).

- Abby Arthur Johnson, "Literary Midwife: Jessie Redmon Fauset and the Harlem Renaissance" (1978).

- Carolyn Wedin Sylvander, Jessie Redmon Fauset, Black American Writer.

- Allen, Carol. Black Women Intellectuals: Strategies of Nation, Family, and Neighborhood in the Works of Pauline Hopkins, Jessie Fauset, and Marita Bonner. NY: Garland, 1998.

- Austin, Rhonda. "Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882-1961)." in Champion, Laurie. ed, American Women Writers, 1900-1945: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2000.

- Calloway, Licia M. Black Family (Dys)Function in Novels by Jessie Fauset, Nella Larsen & Fannie Hurst. NY: Peter Lang, 2003.

- Harker, Jaime. America the Middlebrow: Women's Novels, Progressivism, and Middlebrow Authorship between the Wars. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 2007.

- Keyser, Catherine. Playing Smart: New York Women Writers and Modern Magazine Culture. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2010.

- Olwell, Victoria. The Genius of Democracy: Fictions of Gender and Citizenship in the United States, 1860-1945. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2011.

- Tarver, Australia. "'My House and a Glimpse of My Life Therein': Migrating Lives in the Short Fiction of Jessie Fauset." in Tarver, Australia and Barnes, Paula C. eds. New Voices on the Harlem Renaissance: Essays on Race, Gender, and Literary Discourse. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 2005.

- Tomlinson, Susan. "'An Unwonted Coquetry': The Commercial Seductions of Jessie Fauset's The Chinaberry Tree." in Botshon, Lisa and Goldsmith, Meredith. eds. Middlebrow Moderns: Popular American Women Writers of the 1920s. Boston: Northeastern UP, 2003.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jessie Redmon Fauset. |

| Library resources about Jessie Redmon Fauset |

| By Jessie Redmon Fauset |

|---|

- Profile at "Harlem Renaissance: A Gale Critical Companion"

- The Black Renaissance in Washington, DC Library.

- The Crisis Archives, Vol. 1–25, Modernist Journals Project, Brown University & University of Tulsa

- Jessie Redmon Fauset profile; "Voices from the Gaps", University of Minnesota

- Jessie Redmon Fauset portrait by Laura Wheeler Waring, 1945, at the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

- Photograph of Jessie Redmon Fauset, 1923, from Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

- Photograph of Jessie Redmon Fauset, n.d., from Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

- Fennell, D.K. (February 15, 2011). "Jessie Fauset tells how to face despair". Blog: Hidden Cause, Visible Effects.

- Jessie Redmon Fauset at Find a Grave