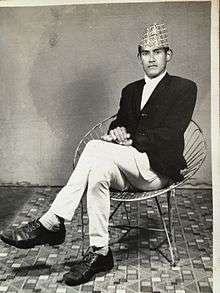

Jaybahadur Hitan Magar

Jaybahadur Hitan Magar (17 July 1949 – 11 December 2009) was a politician, campaigner, writer and literati of Nepal, and a member of the Nepalese Congress Party (NC). He campaigned for a fair involvement of marginalised communities and groups of people within the NC. He was popular among the Indigenous Ethnic people of Nepal, particularly within the Magar Community. He fought for these people’s equal rights and opportunities in the authority. He voiced their concerns, mainly through written articles but also through public speaking. He served in the Government prior to entering into full-time politics and is noted as being the main driving force behind establishing the Nepal Magar Association (NMA). He was founding Secretary of the NMA and served three terms of office. He significantly contributed to organizational development of the NMA, and the formation and expansion of the Nepalese Magar Student Association (NMSA). Popular leaders such as Suresh Ale, Baburam Rana, Girija Prasaada Koirala, Manbir Garbuja, Parasuram Tamang, MS Thapa, Gopal Gurung, Ramkrishna Tamrakar, Gorebahadur Khapangi, Ramprasad Paudyal were among his contemporary friends. Hitan had great interest in Nepalese literature and indeed wrote several poems, song lyrics, dramas, short stories and articles on a wide variety of national, cultural and political topics. He died on 11 December 2009 after suffering from long term paralysis following a stroke in 1999, at his home in Butwal, Nepal.

Biography

Birth, childhood and family

Hitan was born on 17 July 1949 at ward number 1, Arewa, Paundi-Amarai, Gulmi District, Nepal. He was third among 6 siblings of father Padamsing Hitan Magar MC and mother Hastikumari. He had one elder brother Ganga, two younger brothers Purna and Ramesh; one elder sister Tulsi, and one younger sister Bhimi.

Hitan’s father had two wives Hastikumari and Gauri, but sadly both died at early age due to serious illness. His father served in 4/8 Gurkha Regiment in British-India where he was awarded a Military Cross (MC) for his bravery during the Second World War. Even after his retirement, Padamsing continued to receive invitations from his regiment to celebrate VC day in May, and such was his standing in the international community, the Indian government would also invite him to mark their annual Independence Day celebrations in August in Delhi, so he often travelled to India, sometimes twice a year, spending several weeks in route. This nomadic life style of Hitan’s father and early death of his mothers put all the responsibilities of raising his siblings squarely on Hitan’s shoulders.

Hitan grew up in the hardship of mountainous rural life. He attended and successfully completed high school alongside carrying out a daily routine working in the fields, rearing cattle, fetching water and collecting firewood. At the age of 20, he married Premkumari from Gwalichaur, Baglung. Subsequently they were blessed with three sons; Bijay, Ajay and Sanjay.

Education and occupation

Magar youths in the 1950s and 60s spent their time working on farms, portering and generally enjoying life by taking part in folk music, sing-a-longs and dances. Hitan’s father promoted the value of a good literacy and always emphasized that Magar children should attend school. Indeed, he wanted more than anything that his own children would achieve a good standard of education instead of working on the land and tending cattle. With his father’s dedicated guidance Hitan completed higher primary school education at his village and then went to a nearby town, Tamghas, to finish his secondary school education. It is said that Hitan was the first person, at that time, to achieve a high school education in the whole village, and as a result of this qualification became head master of Sarbodaya High School in Amarai, albeit only a short period of time.

Despite this teaching job, Hitan was always involved in the daily household routine, especially looking after his younger brothers and sister, whilst still finding the time to work the fields and tend the cattle. Being an educated youth, he felt that it was also his responsibility to serve the community.

In 1966, whilst still balancing his family and social life, Hitan entered into Government service in the Department of Land Reform. By taking up this civil servant post he broke the Magar tradition by not joining the British or Indian Army as a Ghurkha soldier. His first posting was in Dailekh. During this career he served in many places including Pyuthan, Baglung, Palpa, Tamghas, and Bhairahawa in the mid-west of Nepal.

Hitan believed that education made people wise. With this in mind, he pursued part-time education in the evenings and weekends while he worked in Government Service during the day. Eventually, this hard work paid off. In 1972, he successfully completed the Intermediate in Arts (IA) from Dhaulagiri Mahendra College, in Baglung and in 1979, achieved a Bachelor in Arts (BA) from Tribhuwan University, Kathmandu. Yet still he wanted to further his higher education either in Kathmandu or in India and was even prepared to give up his job in the service of the Government to achieve his goal. However, he could not fulfil his dream of gaining a master's degree or PhD due initially to his poor family background and then later, because he had too many commitments in politics and volunteering.

Unfortunately, Hitan was never promoted during his 12 years Government Service despite his higher education qualifications. Such unfair treatment forced him to resign from the service, which left a bitter taste in his mouth throughout his life, although he did have a few proud moments during his working life. Sometimes he would get appointed as the temporary head of the department. However, it was the discriminative policy of Nepalese Government which made Hitan most frustrated. At that time, Nepalese nationals were few and far between in Public Service. Indeed, only one of his department colleagues was native Nepalese, who was from Newar. According to his diary, most of the time Hitan was tasked with carrying out field investigations so would have to walk up and down the hills and through the remote villages, facing the harshest of weather conditions that the foothills of the Himalayas could throw at him. On many occasions he endured lack of food, drink, proper sleep or rest in pursuit of carrying out his employment duties and as a result suffered many times with his health.

In 1980, at the age of 31, Hitan resigned from the service of the Government and dedicated his life entirely to community service and politics in the Nepali Congress (NC). Full democracy arrived in Nepal in 1990. After the general election, the NC formed a Government and in 1992, Hitan was appointed as a board member of Lumbini Development Fund by the NC led Government.

Literati

Hitan had a keen interest in Nepalese literature and appears to have been involved from his student days and early stages of his time in the Government. Indeed, whilst working as a teacher and also during his service in Baglung he staged plays which were written and performed by himself. Occasionally he would attend concerts and sing folk songs (JHAMRE) with local young women during festive seasons. He has written many songs, most of which sound as Nepali folk lyrics. He enjoyed studying novels, poems, and other aspects of literature throughout his life.

A narrative poem written by him titled ‘Swargama Bhetieka Bhanu, Laxmi ra Lekhanath’ indicates that Hitan was impressed with top level Nepalese poets - Bhanubhakta, Laxmiprasad and Lekhanath and although he takes part in almost every literary discipline, he appears not to have joined any literary groups or organizations. To date, 44 poems, 36 songs, 2 narrative poems, 11 stories, 2 plays, 3 articles have been found in hand written manuscripts and although unfortunately he could not publish these as a book while he was alive, the majority of them have now been published in newspapers and magazines under the pen name ‘Avagi Hitan’.

Journalist and writer

In Hitan’s mid life, after leaving the government service in 1980, he started writing regularly for local and national newspapers, and in the yearbooks of various organizations. His articles, based on current political affairs, Indigenous Ethnic people of Nepal and ex Ghurkha servicemen were published in newspapers such as Chautary, Lumbini, Rajyasatta, and Nepal Pukar.

In 1981, Hitan became a representative of the New Light, Halchala and Kongpi newspapers which delivered messages and highlighted the issues of indigenous ethnic nationalities in Nepal. Hitan’s writings predominantly supported these people’s rights.

The NMA used to publish yearbooks - Langhali, Lafa, Jhorak and Gyahat. Hitan was a member of the editorial group of Langhali. He wrote several articles in these yearbooks in relation to Magar history, culture and language, and worked hard to spread messages raising political awareness of the government’s inequality policy towards the Magar and other ethnic communities, and although most of his articles were found handwritten, he had in fact published a book titled ‘Nepal’s Domestic Policy and Democracy’ in 1981.

Hitan believed on action rather than words but was more comfortable with the pen than with the spoken word as a vehicle for delivering his messages and would frequently deliver novel thoughts and ideas to the public through newspaper articles. However, he was not averse to giving speeches at meetings and rallies. He had been to many doorsteps of rural communities during his civil servant days and had witnessed the problems of Nepalese citizens very closely, hence, he always used to say that the monarchy led single party system, the Panchayat, must bring reform in public sectors and providing equal opportunities to all indigenous and ethnic groups. He would further content that only then would National union and the comprehensive development of Nepal occur.

Political servant

During and after his time as a student Hitan had developed a keen interest in politics and had read and studied many books based on philosophy and the theories of Lenin, Mao and Marx, so one could say that he might have been influenced by communist ideology. However, as part of his job, he had to communicate with different level of bureaucrats, from village and district chiefs to the regional governors of the Panchayat Party led government. He seemed to have intentions at one stage to be actively involved in politics and even become a member of Panchayat but ironically he lost interest in this party due to its apparent acceptance of inequality and corruption, favouritism of the monarchy, and support of one-party rule. Instead, towards the end of his civil servant career, he had become so impressed with the ideology of Bishweshwar Prasad (BP) Koirala who was in exile in India, and his political ideologies - Social Democracy and National Reconciliation, Hitan became a member of the NC.

Towards the end of the 1970s, Hitan became involved in opposition politics but information contained in his diaries indicates that he realised his position as a civil servant would be a barrier. Occasionally, he would manage to escape from work to attend the rallies of dissident political parties. In the end, he resigned from his Government job in April 1980 after being posted to Bhairahawa and openly entered into a full-time politics when he took up membership of the NC. Shortly before his resignation, Hitan had attended assemblies in Bhairahawa, Butwal, and Narayanghat to hear BP Koirala speak. He had the good fortune to meet BP face to face at Narayanghat when they spoke of his desire to resign from his job and get involved actively in politics. BP was very pleased to see a young and enthusiastic Hitan and assured him that he would meet him in Kathmandu in the future.

In 1981, a National referendum was held to decide whether Nepal should stick with the Single Party System or move to a new Multi Party system. Hitan openly and actively campaigned for the Multi Party System in the run-up to this referendum but believed that the vote was neither free nor fair. Unfortunately, and perhaps unsurprising from Hitan’s point of view, the result was to keep the single party system. Subsequently, opposition parties were kept under a tight grip. Yet, this did not deter Hitan. His active involvement in the opposition politics continued at a faster pace and in 1983 he became Assistant Secretary of the NC in Rupandehi, and later that year he took part, officially, in a development seminar held at Gaindakot. All of the NC’s top leaders such as BP Koirala, Ganeshman Singh, Krishna Prasad Bhattarai, Jamansing Gurung were present at that seminar. This was Hitan’s first interaction, training and learning opportunity since becoming fully committed to politics, with a clear vision of what organizational changes were needed. He wanted to attract more ethnic and indigenous people to politics but unfortunately from this point forward, Hitan’s political journey went through hardships and struggles.

In 1990, full democracy came to Nepal following what is now known as the popular people’s movement. By this time Hitan had been taking part in a number of activities including attending opposition rallies and assemblies, BP Memorial Day,

National Reconciliation Memorial Day and Election boycotting movements to name a few. He was jailed many times and faced police brutality as well as threats from thugs who supported the tyranny. In April 1981, he was arrested and jailed in Butwal, along with fellow activist Mr Gautam, while campaigning against the forthcoming national general election. In December 1982 trouble flared at a regional level general assembly of the Nepal Student Association which was due to be opened by the NC party’s Chief-minister Girija Prasad Koirala. Armed Police moved in using battens after an order was given by the Senior District Officer of Taulihawa. Hitan, Koirala and dozens of party members received seriously injuries.

In July 1983, another incident occurred, this time in Butwal. BP Memorial Day was being organised by the NC. Hitan was arrested by police while posting pamphlets and in December 1983, he again faced police brutality while campaigning for National Reconciliation Memorial Day. Three months later an attack took place in Kerwani, Rupendahi which left an unforgettable scar on Hitan’s life. 300 party members including Girija Prasad Koirala had gathered at a meeting at Puspananda Giri’s house. Suddenly, police arrived charging people with battens which resulted in Hitan’s close friend and active party member Yadavnath Alok dying from injuries sustained in this unprovoked and barbaric attack. Hitan himself was also seriously injured from the brutality of that incident. During a civil unrest in June 1985, he was again arrested along with other party members by police investigating an alleged bomb plot. While playing an active role on behalf of NC during the popular uprising in 1990, Hitan was arrested and jailed in Bhairahawa. He was freed 2 months later, on the day when King Birendra lifted restrictions on Multi Party System. The following day, the Chief Commander of the revolution Ganeshman Sing was proposed to become the Prime Minister of Nepal but instead Ganeshman offered the Premiership to the Chairman of the NC Party, Krishna Prasad Bhattarai which came as a big surprise to Hitan who had always pushed for the democratic rights and equal opportunities of ethnic and indigenous groups.

In 1992, a General Election was declared. Competition and lobbying within the party began for the allocation of tickets for the parliamentary candidacy. Marred by favouritism, cronyism and nepotism the election tickets were distributed to those who had not even been actively involved in the revolution. Such unfair practices demoralised members, including Hitan who had been totally committed to the party. In the aftermath of people’s revolution in 1990, political parties who had been promoting ethnic people’s right began to sprout up across Nepal and in 1991, the Rastriya Janamukti Party was formed under the leadership of Gorebahadur Khapangi Magar. He was regarded as the voice of indigenous and ethnic groups, with membership predominantly coming from ex servicemen, and the indigenous and ethnic people of Nepal, many of whom were previously members of the NC and the Communist Party of Nepal – also known as the United Marxist Leninist (CPN-UML). Hitan was also asked to join but felt that he was unable to leave the NC due to his strong ideology and loyalty to the Party. He instead promised to fight on within the NC for the rights and equality of the Ethnic, Indigenous, Dalit and Muslim societies, and it is evident in his articles that he never hesitated to voice such issues. He used to campaign that the ruling party, Rastriya Prajatantra, should work together with small parties such as Sadbhawana, and Rastriya Janamukti in order to strengthen and promote parliamentary democracy.

NC won by a majority in the 1992 General Election. Girija Prasad Koirala became the Prime Minister and formed the NC led government. In recognition of all the hard work Hitan had put in over the years, GP Koirala appointed him as an executive member of Lumbini Development Fund (a body to oversee development of the site where Lord Buddha was born). Unfortunately, within a couple of years Koirala was hit by a revolt from his own MPs and had to face a vote of no-confidence. Predicting possible defeat, Koirala called a General Election in 1994. This caused strife within the NC with the main Party leaders Ganeshman, Krishna Prasad, and Koirala all having their own supporters. Young leaders also started voicing their concerns. Nevertheless, Hitan endeavoured to bring balance among the young and senior leaders. He supported Koirala during this unsettled period of time and was assigned to the party development campaign in his birthplace Gulmi and Rupandehi region. In the mean time, MPs’ candidacy tickets were distributed and election campaign kicked off. Yet again the MPs’ tickets were given to the wealthy and those who promoted favouritism.

Unfortunately, from Hitan’s point of view, Nepalese citizens decided not to stand behind the NC this time which resulted in no party getting an absolute majority. CPN-UML formed a coalition government with NC, although finger pointing, accusation and fierce criticism among the parties continued at an epidemic level. Formation of the full cabinet could not be achieved even months after the election so the communist led government could not continue. Consequently, in 1995 it too had to declare a mid-term general election. Hitan yet again objected to such an unsustainable move and expressed his concerns by publishing political articles in the papers. Hitan continued to be an active member of the party by opposing the ‘wrong cultures’ within it and attempting to guide it in the right direction. In 1996, the party tasked him with a campaign to promote public awareness. He spent two weeks with MP Shivaraj Joshi in Gorkha during this campaign.

Now in his late 40’s, Hitan was beginning to recognize the contributions of the older generation leaders, such as BP, Girija, Ganeshman, and Krishna Prasad who had led the 1960, 1980 and 1990 uprisings. He strongly supported the party leadership but also believed that control of the party should be transferred to the younger generations. Such stances are evident in his articles named ‘Responsibility of young generation’ and ‘Appeal to youth on national building’ in which he criticised the older leaders, challenging them to ‘Provide employment and food or otherwise handover the leadership’.

Social campaigner

Hitan’s social campaigning largely related to three areas:

- Helping rural people to obtain governmental services

- Advocating equal opportunities and rights for Madhesi, Dalit, Indigenous Ethnic people, and ex-servicemen

- Preserving the language, culture and tradition of the Magar community, unearthing its lost history, and raising its awareness.

He believed that the public should be able to receive free governmental services fast and easily, which, ironically, was not the case in Nepal. Dishonesty, fraud and delays were wide spread in the government with Rural Communities, the uneducated and the poor being the main groups at the sharp end of this corruption. The Tharu, Madhise, Dalit, and Indigenous Ethnic people could not get jobs in the public services. In an attempt to right these injustices, Hitan would provide legal consultation, advice and guidance to help them to claim what they were entitled to. In this regard people considered him as a true leader.

Hitan believed that the country would not be able to develop comprehensively until the government provided full and equal opportunities and rights to all people, which included all the discriminated groups and that equal opportunity was impossible without the country being united. In 1980, he coordinated an assembly of Nepal Mangol Ethnic Groups in Bhairahawa. His friends Premsing Limbu from Sunsari, Leader of Mangol National Organisation Gopal Gurung, Editor of Kongpi and Halchal weekly Ghal Rai assisted him in this endeavour. This assembly is now considered a key step towards the foundation of today’s Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN).

Hitan is recognized as one of the first campaigners for the rights of Indigenous Ethnic people of Nepal. He helped to raise awareness of their plight by publishing numerous articles in local and national news papers and giving advice on how to establish these groups’ rights and power in the authority. He took part in various seminars and assemblies of NEFIN, representing Rupendehi, his home region and closely worked with founding General Secretary Suresh Ale Magar and other Indigenous leaders including Gore Bahadur Khapangi Magar and Parasuram Tamang.

Hitan was well aware of the issues surrounding ex Ghurkha soldiers. Exploitation of the Ghurkhas by political parties in Nepal was common and although he was not himself an ex-serviceman, he helped their organisations by taking advisory roles on their committees. While Sherbahadur Gurung was the Chairman of the Nepal Ex-Serviceman Association, Hitan keenly took a part in their activities and provided advice and guidance on their organisational development. He raised awareness within his NC peers and impressed on them that the ex-servicemen organisations must not be mistreated. In his articles he wrote about the ex-servicemen’s contributions in the 1950s and 1960s revolutions in Nepal and that this should never be underestimated nor be forgotten.

The Nepal Magar Association

Hitan’s most significant contribution relates to his work for the Magar community. He raised awareness that the Magar people across the country were underprivileged and that it was only possible to get out of this situation by being united and forming organized associations, hence, he started dialogue with and between Magar leaders and intellectuals. After many years of consultation he helped form the Nepal Langhali Pariwar which later became the Nepal Magar Association (NMA). In 1971/72, he had met Durgabahadur Rana in Palpa, and Kabiraj Pun in Mangalapur, Butwal at their homes and in 1973, he travelled to Kathmandu where he met up with a Nepalese Army Colonel Shreeprasad Budathoki, and MP Bhimbahadur Budathoki. They discussed the prospect of forming an organisation to unite Magar which he followed up by arranging a seminar in Palpa involving Magar students and intellectual personalities. Brain storming was carried out on forming Magar Association at the national level.

Hitan seemed to have rapidly started home works to form ‘Langhali Pariwar’ after being posted to Bhairahawa in 1975. He began consultation with Magar residents and academics including Sherjang Thapa, Boond Rana, and Amarbahadur Thapa. During this time the Government was threatening to take action against those who voiced support for racial freedoms and equal rights. Nevertheless, Hitan felt compelled to establish a national Magar organisation despite his position as a civil servant and he played a key role in forming Kanung Langhali Magarati Bhasa in June 1975. Amarbahadur Thapa and Boond Rana were appointed as Chairman and Vice Chairman respectively of its working committee. Unfortunately, because of his position in the government Hitan always had to remain behind the scenes but using his legal knowledge he was able to help with the writing of the constitution of this newly formed organisation. Hitan had a great interest in volunteering for his community but did not have much freedom to do so due to being a member of the government authority. Government officials were restricted from taking part in social and political activities, but following his resignation he was able to volunteer freely in the social campaigning as well as politics. In 1980, in partnership with Baburam Rana he conceived a road-map to form a Magar Reform Committee at each Magar village which laid out 20-point improvement plan. Some of these plans involved that Magar communities should:

- Reduce spending on social, cultural and religious rituals,

- Minimize alcohol consumption,

- Preserve Magar language, culture, and costume, and

- Establish a fund to provide financial help.

Following the launch of this programme, Hitan spent time selling the idea to the Magar communities by making door to door calls to their homes. Later, these statements were adopted into the constitution of the NMA as the main objectives of the organisation.

Later in 1980, Kanung Langhali Magarati Bhasa was renamed as Kanung Langhali Pariwar Rupandehi. A new committee was selected which included Baburam Rana as Chairman, Manbir Garbuja as Treasurer, and Hitan became Secretary. The following year, Hitan played a major role in organising the very first assembly to be attended by all of the Magar communities throughout Nepal. A Nepal Langhali Pariwar Sangh acting Committee was formed at this historical assembly which was held in Butwal.

In 1982, the Nepal Langhali Pariwar Sangh was officially established with Hitan selected as the Secretary of the organisation, a role which he held for two more terms. During these tenures, and beyond, he continued working closely with several national-level Magar leaders including Hembahadur Pun, Suresh Ale, MS Thapa, Gorebahadur Khapangi, Dilipsing Ale, Durgabahadur Rana, Baburam Rana, Manbira Garbuja, Yambahadur Budathoki, Kesharajang Baral and Dr Harshabahadur Budha. By 1983, he was playing a significant role in forming Magar organisations at district level. Realising that without the contribution of young generation the social movement would not be successful, he proposed greater participations of the Magar youth and as a result of his thinking, Magar Students Associations were started to be set up in colleges and universities across the country. Hitan lead this project himself in the Mid-west region of Nepal. He personally visited the colleges in Rupandehi, Palpa, Gulmi, Arghakhachi, Nawalparasi, Kapilwastu, Dang; met with the students and helped them set up Magar Student Unions. As of 2014, there were Magar Student Associations in over 500 colleges and universities in almost 65 districts of Nepal. It is not unreasonable to say that this is the result of Hitan’s great vision.

Magar had a proud history and rich culture but unfortunately they had been hidden and were diminishing at that time so rediscovery and protection was necessary. Therefore, in 1989, under Hitan’s direction, a Magar Culture and History Council was established and he took responsibility of its Chairmanship. In the same year the Magar Language and Script Council was formed under Kesherjang Baral’s chairmanship. In the course of writing a book on the Magar History, Hitan studied several historical books about Magar, visited Magar villages, met with and had many conversations with elder Magars. Sadly, he became ill so the book could not be completed. Draft copies of his collections and hand written scripts were found amongst his private papers after he died.

The NMA had, over the years, been expanding and became stronger. The leadership had been handed over to younger generations, but much of the appreciation for these changes goes to the role that Hitan played in the early years. Regrettably, his physically health was failing and as a result he could not continue playing an active role, particularly during the tenure of Gorebahadur Khapangi’s chairmanship in 1997. He was however, appointed as an advisor to the NMA and was honoured in 2000, during the NMA’s 7th National Grand Assembly in Dharan, with the ‘Harka Award’ for his selfishness and lifelong contributions towards the Magar community.

Personality

Hitan was a softly spoken gentleman who enjoyed visiting places and meeting people. He enjoyed taking part in social meetings, political assemblies, and literary gatherings. Staying home and carrying out household chores were not amongst his favourite things to do. He loved reading newspapers, magazines, and books on philosophy, politics, society, and current affairs and would take every opportunity that he could to get out into the rice terraces and hillside forests at his home village in the foothills of the Himalayas to read his books. Lack of money did not stop him buying something to read and he would even buy books on goodwill credit which he had earned over the years making door to door visits. He never liked earning merit by visiting the gods and goddesses in their temples. Serving the community was at his heart.

When not out on party business or other official work, he liked to lead a simple uncomplicated lifestyle, rising early, drinking lots of tea and meeting up with friends to drink more tea. Evenings were often taken up attending social or political meetings but if this was not the case then he would often be found at home studying or formulating strategies for setting up and progressing his social and political activities. Hitan’s friends mainly included social activists and campaigners, intellectuals, politicians, and literati and he would often invite them home to have meetings or debates. He was always focused on community development and would frequently worry about national affairs. In contrast, he did not seem to have the same level of concern about family matters. He had been living with his family in a rented room in Bhairahawa when he left his government job. His three sons used to go school but his bank account was frequently empty so he was often unable to pay their school fees. Despite this, he continued being involved in social and political activities to the detriment of his family.

Hitan seemed to have a belief that if too much care and love was given to his family then they would be spoiled which could have been the reason behind why he never had time for his wife and sons. He never took them on holiday, played with them or sat with them to help them with their homework. It was very hard for him to find time to fulfil his fatherly responsibilities, but he would constantly go out of his way to help his close relatives to promote unity among family members and provide advice in raising general awareness. He dreamed of his sons becoming either like himself, the civil servant, or an officer in the Nepal Police or Nepal Army. He did not like the idea of them becoming British or Indian Ghurkha soldiers as, in his opinion, Ghurkha soldier recruitment was one of the major causes of indigenous nationals in Nepal being so backward.

Hitan also believed that ambition could only be achieved by dedication and hard work. He had vowed that he would not to use any hair oil on his head, smoke or drink until he completed his degree and to be fair to him, he only started doing these after passing his final bachelor's degree exam in 1978. He also became addicted to the Madhesi traditions of chewing betel and tobacco whilst living in Bhairahawa and developed a habit of drinking at home on his own rather than out in the restaurants with friends.

Hitan was not a tall man at 1.7m. He would comb his black hair straight up and usually wore a white shirt, black waistcoat, black trousers and black shoes. In contrast, when attending formal events he would wear full Nepali national costume - Daura-suruwal and Dhaka Topi. With his short hair, shaven face and fit and healthy physique, he cut quite a dashing figure albeit resembling a Lahure (a Gurkha serviceman in the Indian or British Army).

He enjoyed simple Nepalese food; rice, vegetables, dahl, and chutney, and seemed to have been obsessed with tea. It was not uncommon for him to have 6-8 cups a day and would never say no if someone offered him more.

Final years

Hitan had lived through poverty during his early life but fortunately, his financial situation had improved in his final years despite receiving no benefits in recognition of his selfless service towards the public and the Party. Sadly, during those years he suffered both mentally and physically so he was not able to enjoy them to the full. During Hitan’s active years, there was a great deal of dishonesty, mistrust and dispute among the NC party members caused by the greed of the people holding the higher positions of power. Hitan was very popular among working-class people and local level party members, but despite this he had missed potential opportunities of getting political appointments which could have been attributed to not having a close relationship with any of the Central Party Leaders. In an attempt to close this gap he had been living in Tikhedewal, Kathmandu since 1996 but there was no stability or progression in the political environment in Nepal at that time. The Maoist Party had declared and fought a bloody campaign against the monarchy and other political parties which had also impacted negatively on Hitan’s political life.

The Magar community had also fallen victim to this political strife and disintegration had been apparent in the NMA. Meanwhile, in his own family environment, life was far from rosy and his relationship with his wife had been deteriorating. All of this turmoil may well have been the cause of his stressful mental health. In addition, he was diagnosed with high blood pressure and diabetics. Tragically, he suffered a stroke in December 1999. His wife Premkumari and some of his extended family took him to a Teaching Hospital in Kathmandu for treatment and his sons Bijay and Sanjay returned to Nepal to be with him. Thankfully, he responded to treatment and his condition improved after a month or so but he never fully recovered. Walking became impossible and he lived the rest of his life with this disability. As a result, and devastatingly from his point of view, he was never again able to actively participate in his political and social activities. Treatment continued. He was taken to a variety of centres throughout Nepal and even some in India to see not only medical doctors but others offering Ayurvedic, Chinese and Traditional treatments. Despite these treatments, he remained house-bound and confined to a wheelchair but fortunately received excellent care and love from his family. Sadly, after struggling with the illness for 10 years, he died at home in Milan Chock, Butwal, Nepal on 11 December 2009. He was 64 years old.

Published works

Hitan had himself published a book ‘Domestic policy and Democracy of Nepal’ in 1980. His eldest son Bijay Hitan Magar published a book titled ‘Jaybahadur Hitan Magar-Biography and Deeds ’ in 2014 which contains several of Hitan’s articles on the Indigenous people and politics of Nepal. It also includes other examples of Hitan’s written work including song lyrics, poems, short stories and plays.

The Jaybahadur Hitan Magar Memorial Award

In 2014, the ‘Jaybahadur Hitan Magar Memorial Award’ was founded by Hitan’s family. Managed by the Jitbahadur Singjali Magar Literary Academy, a Rs 150,000 fund has been set up in Hitan’s memory to give recognition to people and/or organisations that make significant contributions towards the Magar community. Recipients of the award will be selected annually and will receive Rs20,000.

Notes

- Biyaya, Hitan Magar (December 12, 2014). Jaya Bahadur Hitan Magar Byaktitwa Ra Krititwa (Biyaya Hitan Magar ed.). Nepal: Nepal Magar Association. ISBN 978-9937-2-8974-0.