Jaws (novel)

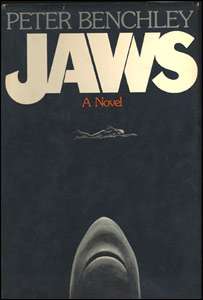

Cover of the first hardcover edition | |

| Author | Peter Benchley |

|---|---|

| Cover artist |

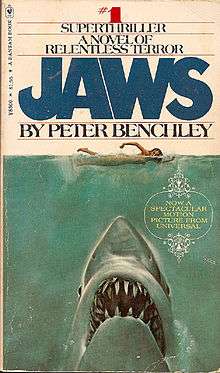

Paul Bacon (hardcover) Roger Kastel (paperback) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Horror |

| Publisher |

Doubleday (hardcover) Bantam (paperback) |

Publication date | February 1974[1] |

| Pages | 278 |

| LC Class | PS3552.E537 |

Jaws is a 1974 novel by American writer Peter Benchley. It tells the story of a great white shark that preys upon a small resort town and the voyage of three men trying to kill it. The novel grows out of Benchley's interest in shark attacks after he learned about the exploits of shark fisherman Frank Mundus in 1964. Doubleday commissioned him to write the novel in 1971, a period when Benchley struggled as a freelance journalist.

Through a marketing campaign orchestrated by Doubleday and paperback publisher Bantam, Jaws was incorporated into many book sales clubs catalogues and attracted media interest. After first publication in February 1974, the novel was a great success, with the hardback staying on the bestseller list for some 44 weeks and the subsequent paperback selling millions of copies in the following year. Reviews were mixed, with many literary critics finding the prose and characterization lacking despite the novel's effective suspense.

Film producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown read the novel before its publication and bought the film rights, selecting Steven Spielberg to direct the film adaptation. The Jaws film, released in June 1975, omitted many of the novel's minor subplots, focusing more on the shark and the characterizations of the three protagonists. Jaws became the highest-grossing movie in history up to that point, becoming a watershed film in motion picture history and the father of the summer blockbuster film. Three sequels followed the film.

Plot summary

The story is set in Amity, a seaside resort town on Long Island, New York. One night, a massive great white shark kills a young tourist named Chrissie Watkins while she skinny dips in the open waters. After finding what remains of her body washed up on the beach, investigators realize she was attacked by a shark. Police chief Martin Brody orders Amity's beaches closed, but mayor Larry Vaughn and the town's selectmen overrule him out of fear for damage to summer tourism, the town's main industry. With the connivance of Harry Meadows, the editor of the local newspaper, they hush up the attack.

A few days later, the shark kills a young boy named Alex Kintner and an old man not far from the shore. A local fisherman, Ben Gardner, is sent by Amity's authorities to kill the shark but disappears on the water. Brody and deputy Leonard Hendricks find Gardner's boat anchored off-shore, empty, and covered with large bite holes, one of which has a massive shark tooth stuck in it. Blaming himself for these deaths, Brody again tries to close the beaches, while Meadows investigates the Mayor's business contacts to determine why he wants to keep the beaches open. Meadows uncovers links to the Mafia, who pressure Vaughn to keep the beaches open in order to protect the value of Amity's real estate, in which the Mafia invested a great deal of money. Meadows also recruits marine biologist Matt Hooper from the Woods Hole Institute to advise them on how to deal with the shark.

Meanwhile, Brody's wife Ellen misses the affluent life she had before marrying Brody and having children. She starts a romantic relationship with Hooper, who is the younger brother of a man she used to date, and the two have a brief affair in a motel outside of town. Throughout the rest of the novel, Brody suspects they have had a liaison and is haunted by the thought.

With the beaches still open, people pour to the town, hoping to glimpse the killer shark. Brody sets up patrols to watch for the fish. After a boy narrowly escapes another attack close to the shore, Brody closes the beaches and hires Quint, a professional shark hunter, to kill the shark. Brody, Quint, and Hooper set out on Quint's vessel, the Orca. The trio are soon at odds with one another. Quint's methods anger Hooper, especially when he disembowels a blue shark, and then uses an illegally fished unborn dolphin for bait. All the while, Quint taunts Hooper as a rich college boy. Brody and Hooper also argue, as Brody's suspicions about Hooper's possible affair with Ellen grow stronger; at one point, Brody unsuccessfully attempts to strangle Hooper.

Their first two days at sea are unproductive and they return to port each night. On the third day, Hooper wants to bring along a shark proof cage. Initially Quint refuses, considering it a suicidal idea, but he relents when Hooper offers him a hundred dollars. On the ocean, the shark finally shows up. Hooper guesses the animal must be at least twenty feet long, and is visibly excited and in awe. After several unsuccessful attempts by Quint to harpoon the shark, Hooper goes underwater in the cage. He resolves to first take photos of the shark, before trying to kill it with a bang stick. However, the shark attacks the cage, and, after ramming the bars apart, kills and eats Hooper.

Larry Vaughn arrives at the Brody house before Brody returns home, and informs Ellen that he and his wife are leaving Amity. Before he leaves, he tells Ellen that he always thought they would have made a great couple. When Brody and Quint return to sea the following day, the shark starts ramming the boat, but Quint is able to harpoon it several times. The shark leaps out of the water and onto the stern of the Orca, ripping a huge hole in the aft section and causing the boat to begin to sink. Quint plunges another harpoon into the shark, but as it falls back into the water, his foot gets entangled in the rope, and he is dragged underwater to his death as he drowns. Brody, now floating on a seat cushion, spots the shark swimming towards him and prepares for his death. However, just as the shark gets within a few feet of him, it succumbs to its many wounds, rolls over in the water, and dies before it can kill Brody. The great fish sinks down out of sight, dragging Quint's still entangled body behind it. Brody manages to paddle back to shore on his makeshift float, the lone survivor of the ordeal.

Development

Peter Benchley had a long time fascination with sharks, which he frequently encountered while fishing with his father Nathaniel in Nantucket.[2] As a result, for years, he had considered writing "a story about a shark that attacks people and what would happen if it came in and wouldn't go away."[3] This interest grew greater after reading a 1964 news story about fisherman Frank Mundus catching a great white shark weighing 4,550 pounds (2,060 kg) off the shore of Montauk Point, Long Island, New York.[4][5]

In 1971, Benchley worked as a freelance writer struggling to support his wife and children.[6] In the meantime, his literary agent scheduled regular meetings with publishing house editors.[2] One of them was Doubleday editor Thomas Congdon, who had lunch with Benchley seeking book ideas. Congdon did not find Benchley's proposals for non-fiction interesting, but instead favored his idea for a novel about a shark terrorizing a beach resort. Benchley sent a page to Congdon's office, and the editor paid him $1,000 for 100 pages.[4] Those pages would comprise the first four chapters, and the full manuscript received a $7,500 total advance.[2] Congdon and the Doubleday crew were confident, seeing Benchley as "something of an expert in sharks",[7] given the author self-described "knowing as much as any amateur about sharks" as he had read some research books and seen the 1971 documentary Blue Water White Death.[2] After Doubleday commissioned the book, Benchley then started researching all possible material regarding sharks. Among his sources were the Peter Matthiessen's Blue Meridian, Jacques Cousteau's The Shark: Splendid Savage of the Sea, Thomas B. Allen's Shadows In The Sea, and David H. Davies' About Sharks And Shark Attacks.[8][9]

Benchley only began writing once his agent reminded him that if he did not deliver the pages, he would have to return the already cashed and spent money. The hastily written pages were met with derision by Congdon, who did not like Benchley's attempt at making the book comedic.[2] Congdon only approved the first five pages, which went into the eventual book without any changes, and asked Benchley to follow the tone of that introduction.[4] After a month, Benchley delivered rewritten chapters, which Congdon approved, alongside a broader outline of the story. The manuscript took a year and a half to complete.[8] During this time, Benchley worked in his makeshift office above a furnace company in Pennington, New Jersey during the winter, and in a converted turkey coop in the seaside property of his wife's family in Stonington, Connecticut during the summer.[6] Congdon dictated further changes from the rest of the book, including a sex scene between Brody and his wife which was changed to Ellen and Hooper. Congdon did not feel that there was "any place for this wholesome marital sex in this kind of book". After various revisions and rewrites, alongside sporadic payments of the advance, Benchley delivered his final draft in January 1973.[7]

Benchley was also partly inspired by the Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916 where there were four recorded fatalities and one critical injury from shark attacks from July 1 through July 12, 1916. The story is very similar to the story in Benchley's book with a vacation beach town on the Atlantic coast being haunted by a killer shark and people eventually being commissioned to hunt down and kill the shark or sharks responsible. There is another similarity in the 1916 incident and the book where kids are attacked in a body of water other than the ocean - in the 1916 incident a child and an adult who attempted to save him were attacked and killed in Matawan Creek, a brackish/freshwater creek about 30 miles inland from the Atlantic and in the novel/film Mike Brody is nearly killed in the "pond" which in reality is a small inland cove that connects to the open ocean through a small tributary.

Title and cover

Shortly before the book went to print, Benchley and Congdon needed to choose a title. Benchley had many working titles during development, many of which he calls "pretentious", such as The Stillness in the Water and Leviathan Rising. Benchley regarded other ideas, such as The Jaws of Death and The Jaws of Leviathan, as "melodramatic, weird or pretentious".[3] Congdon and Benchley brainstormed about the title frequently, with the writer estimating about 125 ideas raised.[8] The novel still did not have a title until twenty minutes before production of the book. The writer discussed the problem with editor Tom Congdon at a restaurant in New York:

We cannot agree on a word that we like, let alone a title that we like. In fact, the only word that even means anything, that even says anything, is "jaws". Call the book Jaws. He said "What does it mean?" I said, "I don't know, but it's short; it fits on a jacket, and it may work." He said, "Okay, we'll call the thing Jaws.[3]

For the cover, Benchley wanted an illustration of Amity as seen through the jaws of a shark.[7] Doubleday's design director, Alex Gotfryd, assigned book illustrator Wendell Minor with the task.[10] The image was eventually vetoed for sexual overtones, compared by sales managers to the vagina dentata. Congdon and Gotfryd eventually settled on printing a typographical jacket, but that was subsequently discarded once Bantam editor Oscar Dystel noted the title Jaws was so vague "it could have been a title about dentistry".[7] Gottfried tried to get Minor to do a new cover, but he was out of town, so he instead turned to artist Paul Bacon.[10] Bacon drew an enormous shark head, and Gottfried suggested adding a swimmer "to have a sense of disaster and a sense of scale". The subsequent drawing became the eventual hardcover art, with a shark head rising towards a swimming woman.[7]

Despite the acceptance of the Bacon cover by Doubleday, Dystel did not like the cover, and assigned New York illustrator Roger Kastel to do a different one for the paperback. Following Bacon's concept, Kastel illustrated his favorite part of the novel, the opening where the shark attacks Chrissie. For research, Kastel went to the American Museum of Natural History, and took advantage of the Great White exhibits being closed for cleaning to photograph the models. The photographs then provided reference for a "ferocious-looking shark that was still realistic."[10] After painting the shark, Kastel did the female swimmer. Following a photoshoot for Good Housekeeping, Kastel requested the model he was photographing to lie on a stool in the approximate position of a front crawl.[11] The oil-on-board painting Kastel created for the cover would eventually be reused by Universal Studios on the film posters.[10]

Themes and style

The story of Jaws is limited by how the humans respond to the shark menace.[12] The fish is given much detail, with descriptions of its anatomy and presence creating the sense of an unstoppable threat.[13] Elevating the menace are violent descriptions of the shark attacks.[14] Along with a carnivorous killer on the sea, Amity is populated with equally predatory humans: the mayor has ties with the mafia, an adulterous housewife, criminals among the tourists.[15]

In the meantime, the impact of the predatory deaths resemble Henrik Ibsen's play An Enemy of the People, with the mayor of a small town panicking over how a problem will drive away the tourists.[12] Another source of comparison raised by critics was Moby-Dick, particularly regarding Quint's characterization and the ending featuring a confrontation with the shark; Quint even dies the same way as Captain Ahab.[16][17][18] The central character, Chief Brody, fits a common characterization of the disaster genre, an authority figure who is forced to provide guidance to those affected by the sudden tragedy.[12] Focusing on a working class local leads the book's prose to describe the beachgoers with contempt, and Brody to have conflicts with the rich outsider Hooper.[13]

Publication history

"I knew that Jaws couldn't possibly be successful. It was a first novel, and nobody reads first novels. It was a first novel about a fish, so who cares?"

-Peter Benchley[3]

Benchley says that neither he nor anyone else involved in its conception initially realized the book's potential. Tom Congdon, however, sensed that the novel had prospects and had it sent out to The Book of the Month Club and paperback houses. The Book of the Month Club made it an "A book", qualifying it for its main selection, then Reader's Digest also selected it. The publication date was moved back to allow a carefully orchestrated release. It was released first in hardcover in February 1974,[1] then in the book clubs, followed by a national campaign for the paperback release.[19] Bantam bought the paperback rights for $575,000,[1] which Benchley points out was "then an enormous sum of money".[3] Once Bantam's rights lapsed years later, they reverted to Benchley, who subsequently sold them to Random House, who has since done all the reprints of Jaws.[8]

Upon release, Jaws became a great success. According to John Baxter's biography of Steven Spielberg, the novel's first entry on California's best-seller list was caused by Spielberg and producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown, who were on pre-production for the Jaws film, buying a hundred copies of the novel each, most of which were sent to "opinion-makers and members of the chattering class".[1] Jaws was the state's most successful book by 7 p.m. on the first day. However, sales were good nationwide without engineering.[1] The hardcover stayed on The New York Times bestseller list for some 44 weeks - peaking at number two behind Watership Down - selling a total of 125,000 copies. The paperback version was even more successful, topping book charts worldwide,[20] and by the time the film adaptation debuted in June 1975 the novel had sold 5.5 million copies domestically,[21] a number that eventually reached 9.5 million copies.[1] Worldwide sales are estimated at 20 million copies.[22] The success inspired the American Broadcasting Company to invite Benchley for an episode of The American Sportsman, where the writer wound up swimming with sharks in Australia, in what would be the first of many nature-related television programs Benchley would take part in.[8]

Critical reception

Despite the commercial success, reviews were mixed. The most common criticism focused on the human characters. Michael A. Rogers of Rolling Stone declared that "None of the humans are particularly likable or interesting" and confessed the shark was his favorite character "and one suspects Benchley's also."[23] Steven Spielberg shared the sentiment, saying he initially found many of the characters unsympathetic and wanted the shark to win, a characterization he changed in the film adaptation.[4]

Critics also derided Benchley's writing. Time reviewer John Skow described the novel as "cliché and crude literary calculation", where events "refuse to take on life and momentum" and the climax "lacks only Queequeg's coffin to resemble a bath tub version of Moby-Dick."[17] Writing for The Village Voice, Donald Newlove declared that "Jaws has rubber teeth for a plot. It's boring, pointless, listless; if there's a trite turn to make, Jaws will make that turn."[24] An article in The Listener criticized the plot, stating the "novel only has bite, so to say, at feed time," and these scenes are "naïve attempts at whipping along a flagging story-line."[25] Andrew Bergman of The New York Times Book Review felt that despite the book serving as "fluid entertainment", "passages of hollow portentousness creep in" while poor scene "connections [and] stark manipulations impair the narrative."[26]

Nevertheless, some reviewers found Jaws's description of the shark attacks entertaining. John Spurling of the New Statesman asserted that while the "characterisation of the humans is fairly rudimentary", the shark "is done with exhilarating and alarming skill, and every scene in which it appears is imagined at a special pitch of intensity."[27] Christopher Lehmann-Haupt praised the novel in a short review for The New York Times, highlighting the "strong plot" and "rich thematic substructure."[28] The Washington Post's Robert F. Jones described Jaws as "much more than a gripping fish story. It is a tightly written, tautly paced study," which "forged and touched a metaphor that still makes us tingle whenever we enter the water."[29] New York Magazine reviewer Eliot Fremont-Smith found the novel "immensely readable" despite the lack of "memorable characters or much plot surprise or originality"; Fremont-Smith wrote that Benchley "fulfills all expectations, provides just enough civics and ecology to make us feel good, and tops it off with a really terrific and grisly battle scene".[18]

In the years following publication, Benchley began to feel responsible for the negative attitudes against sharks that his novel engendered. He became an ardent ocean conservationist.[4] In an article for the National Geographic published in 2000, Benchley writes "considering the knowledge accumulated about sharks in the last 25 years, I couldn't possibly write Jaws today ... not in good conscience anyway. Back then, it was generally accepted that great whites were anthropophagus (they ate people) by choice. Now we know that almost every attack on a human is an accident: The shark mistakes the human for its normal prey."[30] Upon his death in 2006, Benchley's widow Wendy declared the author "kept telling people the book was fiction", and comparing Jaws to The Godfather, "he took no more responsibility for the fear of sharks than Mario Puzo took responsibility for the Mafia."[16]

Film adaptation

Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown, film producers at Universal Pictures, both heard about the book before publication at the same time. Upon reading it, both agreed the novel was exciting and deserved a feature film adaptation, even if they were unsure how to accomplish it.[3] Benchley's agent sold the adaptation rights for $150,000, plus an extra $25,000 for Benchley to write the screenplay.[7] Although this delighted the author, who had very little money at the time,[3] it was a low sum, as the agreement occurred before the book became a surprise bestseller.[31] After securing the rights, Steven Spielberg, who was making his first theatrical film, The Sugarland Express, for the Universal producers, was hired as the director.[32] To play the protagonists, the producers cast Robert Shaw as Quint, Roy Scheider as Brody and Richard Dreyfuss as Hooper.[33]

Benchley's contract promised him the first draft of the Jaws screenplay. He wrote three drafts before passing the job over to other writers;[31] the only other writer credited beside Benchley was the author responsible for the shooting script, actor-writer Carl Gottlieb.[33] Benchley also appears in the film playing a small onscreen role as a reporter.[34] For the adaptation, Spielberg wanted to preserve the novel's basic concept while removing Benchley's many subplots and changing the characterizations, having found the characters of the book unlikable.[31] Among the changes were the removal of the adulterous affair between Ellen Brody and Matt Hooper,[35] making Quint a survivor of the World War II USS Indianapolis disaster,[36] and changing the cause of the shark's death from extensive wounds to a scuba tank explosion.[37] The director estimated the final script had a total of 27 scenes that were not in the book.[35] Amity was also relocated; while scouting the book's Long Island setting, Brown found it "too grand" and not fitting the idea of "a vacation area that was lower middle class enough so that an appearance of a shark would destroy the tourist business." Thus now the setting was an island in New England, filmed in Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts.[38]

Released on theaters in 1975, Jaws became the highest-grossing film ever at the time, a record it held for two years until the release of Star Wars.[39][40] Benchley was satisfied with the adaptation, noting how dropping the subplots allowed for "all the little details that fleshed out the characters".[8] The film's success lead to three sequels, which Benchley had no involvement despite drawing on his characters.[41] According to Benchley, once his payment of the adaptation-related royalties got late, he called his agent and she replied that the studio was arranging a deal for sequels. Benchley disliked the idea, saying "I don't care about sequels; who'll ever want to make a sequel to a movie about a fish?". He subsequently relinquished the Jaws sequel rights, aside for a one-time payment of $70,000 for each one.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Baxter 1997, p. 120.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Benchley 2006, pp. 14–17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bouzereau, Laurent (1995). A Look Inside Jaws ["From Novel to Script"]. Jaws: 30th Anniversary Edition DVD (2005): Universal Home Video.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dowling, Stephen (February 1, 2004). "The book that spawned a monster". BBC News. Retrieved January 19, 2009.

- ↑ Downie, Robert M. Block Island History of Photography 1870–1960s, page 243, Volume 2, 2008

- 1 2 Hawtree, Christopher (February 14, 2006). "Peter Benchley: He was fascinated by the sea, but his bestselling novel tapped into a primeval fear of the deep". The Guardian. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Morgan, Ted (April 21, 1974). "Sharks". The New York Times Book Review. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gilliam, Brett (2007). "Peter Benchley: The Father of Jaws and Other Tales of the Deep". Diving Pioneers and Innovators. New World Publications. ISBN 978-1-878348-42-5. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ↑ Perez, Steve (December 15, 2004). "'Jaws' author explores sharks' territory". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Marks, Ben (June 29, 2012). "Real Hollywood Thriller: Who Stole Jaws?". Collectors Weekly. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ↑ Freer, Ian. "The Unsung Heroes of Jaws". Empire. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Sutherland, John (2010). "10: Jaws". Bestsellers (Routledge Revivals): Popular Fiction of the 1970s. Routledge. ISBN 1-136-83063-4. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- 1 2 Curtis, Bryan (February 16, 2006). "Peter Benchley - The man who loved sharks". Slate. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ↑ Willbern, David (2013). The American Popular Novel After World War II: A Study of 25 Best Sellers, 1947–2000. McFarland. pp. 66–71. ISBN 0-7864-7450-5.

- ↑ Andriano, Joseph (1999). Immortal Monster: The Mythological Evolution of the Fantastic Beast in Modern Fiction and Film. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 17–23. ISBN 0-313-30667-2.

- 1 2 Nelson, Valerie J. (February 13, 2006). "Peter Benchley, 65; 'Jaws' Author Became Shark Conservationist". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- 1 2 Skow, John. "Overbite". Time. Vol. 103. February 4, 1974. p76.

- 1 2 Fremont-Smith, Eliot. "Satisfactions Guaranteed" New York - January 28, 1974.

- ↑ Gottlieb 1975, pp. 11–13.

- ↑ Benchley 2006, p. 19.

- ↑ "Summer of the Shark". Time. New York City. June 23, 1975. Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ↑ Knight, Sam (February 13, 2006). "'Jaws' creator loved sharks, wife reveals". The Times. London. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ↑ Rogers, Michael. "Jaws review". Rolling Stone. April 11, 1974. p75.

- ↑ Newlove, Donald. The Village Voice. February 7, 1974. pp. 23–4.

- ↑ The Listener. Vol. 91. May 9, 1974. p. 606.

- ↑ Bergman, Andrew. "Jaws'. The New York Times Book Review. February 3, 1974. p14.

- ↑ Spurling, John. New Statesman. Vol. 87. May 17, 1974. p703.

- ↑ Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher. "A Fish Story ... or Two" The New York Times - January 17, 1974.

- ↑ Jones, Robert F. "Book World", The Washington Post. Sunday, January 27, 1974. p3.

- ↑ Benchley, Peter (April 2000). "Great white sharks". National Geographic: 12. ISSN 0027-9358.

- 1 2 3 Brode 1995, p. 50.

- ↑ McBride 1999, p. 232.

- 1 2 Pangolin Pictures (June 16, 2010). Jaws: The Inside Story (Television documentary). The Biography Channel.

- ↑ Bouzereau, Laurent (1995). A Look Inside Jaws ["Casting "]. Jaws: 30th Anniversary Edition DVD (2005): Universal Home Video.

- 1 2 Friedman & Notbohm 2000, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Vespe, Eric (Quint) (June 6, 2011). "Steven Spielberg and Quint have an epic chat all about JAWS as it approaches its 36th Anniversary!". Ain't It Cool News. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ↑ Bouzereau, Laurent (1995). A Look Inside Jaws ["Climax"]. Jaws: 30th Anniversary Edition DVD (2005): Universal Home Video.

- ↑ Priggé, Steven (2004). Movie Moguls Speak: Interviews with Top Film Producers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 7. ISBN 0-7864-1929-6.

- ↑ Fenner, Pat. C. (January 16, 1978). "Independent Action". Evening Independent. p. 11–A.

- ↑ New York (AP) (May 26, 1978). "Scariness of Jaws 2 unknown quantity". The StarPhoenix. p. 21.

- ↑ Kidd, James (September 4, 2014). "Jaws at 40 – is Peter Benchley's book a forgotten masterpiece?". The Independent. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

Sources

- Baxter, John (1997). Steven Spielberg: The Unauthorised Biography. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-638444-7.

- Benchley, Peter (2006). Shark Life: True Stories About Sharks & the Sea. New York: Random HouseCollins. ISBN 0-307-54574-1.

- Brode, Douglas (1995). The Films of Steven Spielberg. New York: Carol Publishing. ISBN 0-8065-1951-7.

- Capuzzo, Michael (2001). Close to Shore: A True Story of Terror in an Age of Innocence. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0413-3.

- Ellis, Richard (1983). The Book of Sharks. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-613552-3.

- Fernicola, Richard G. (2002). Twelve Days of Terror: A Definitive Investigation of the 1916 New Jersey Shark Attacks. Guilford, Conn.: The Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-575-8.

- Friedman, Lester D.; Notbohm, Brent (2000). Steven Spielberg: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-113-X.

- Gottlieb, Carl (1975). The Jaws Log (in German). New York, New York: Dell. ISBN 978-0-440-14689-6.

- McBride, Joseph (1999). Steven Spielberg: A Biography. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80900-1.

- Yule, Andrew (1996). Steven Spielberg: Father to the Man. London: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-91363-4.