Japan Airlines Flight 123

JA8119, the aircraft involved the accident, taken at Osaka International Airport in 1984 | |

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | August 12, 1985 |

| Summary | In-flight structural failure resulting from incorrect repairs to tailstrike damage |

| Site |

Mount Osutaka-no-one Ueno, Gunma Prefecture, Japan 36°0′5″N 138°41′38″E / 36.00139°N 138.69389°ECoordinates: 36°0′5″N 138°41′38″E / 36.00139°N 138.69389°E |

| Passengers | 509 |

| Crew | 15 |

| Fatalities | 520 |

| Injuries (non-fatal) | 4 |

| Survivors | 4 |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747SR-146 |

| Operator | Japan Airlines |

| Registration | JA8119 |

| Flight origin | Haneda Airport, Tokyo |

| Destination | Osaka Int'l Airport, Itami |

Japan Airlines Flight 123 (日本航空123便 Nihonkōkū 123 Bin) was a scheduled domestic Japan Airlines passenger flight from Tokyo's Haneda Airport to Osaka International Airport, Japan. On Monday, August 12, 1985, a Boeing 747SR operating this route suffered an explosive decompression 12 minutes into the flight and, 32 minutes later, crashed into two ridges of Mount Takamagahara in Ueno, Gunma Prefecture, 100 kilometres (62 miles) from Tokyo. The crash site was on Osutaka Ridge (御巣鷹の尾根 Osutaka-no-One), near Mount Osutaka.

The explosive decompression was caused by a faulty repair performed after a tailstrike incident during a landing seven years earlier. A doubler plate on the rear bulkhead of the plane was improperly repaired, compromising the plane's airworthiness. Cabin pressurization continued to expand and contract the improperly repaired bulkhead until the day of the accident, when the faulty repair finally failed, causing the explosive decompression that ripped off a large portion of the tail and caused the loss of hydraulic controls to the entire plane.

Casualties of the crash included all 15 crew members and 505 of the 509 passengers; some passengers survived the initial crash but subsequently died of their injuries hours later, mostly due to delays in the rescue operation. It is the deadliest single-aircraft accident in history, the deadliest aviation accident in Japan,[1] the second-deadliest Boeing 747 accident and the second-deadliest aviation accident behind the 1977 Tenerife airport disaster.[2]

Aircraft and crew

The accident aircraft was registered JA8119 and was a Boeing 747-146SR (Short Range). Its first flight was on January 28, 1974. It had more than 25,000 airframe hours and more than 18,800 cycles (one cycle equals one takeoff and landing).[1]

At the time of the accident the aircraft was on the fifth of its six planned flights of the day.[3] There were fifteen crew members, including three cockpit crew and 12 flight attendants.[4]

The cockpit crew consisted of the following:

- Captain Masami Takahama (高浜 雅己 Takahama Masami) from Akita, Japan, served as a training instructor for First Officer Yutaka Sasaki on the flight, supervising him while handling the radio communications.[5][6][7] A veteran pilot, having logged approximately 12,400 total flight hours, roughly 4,850 of which were accumulated flying 747s, Masami Takahama was aged 49 at the time of the accident.

- First Officer Yutaka Sasaki (佐々木 祐 Sasaki Yutaka) from Kobe flew Flight 123 as a training flight as part of his requirements to be promoted to Captain.[7] Sasaki, who was 39 years old at the time of the incident, had approximately 4,000 total flight hours to his credit and he had logged roughly 2,650 hours in the 747.

- Flight Engineer Hiroshi Fukuda (福田 博 Fukuda Hiroshi) from Kyoto,[7] the 46-year-old veteran flight engineer of the flight who had approximately 9,800 total flight hours, of which roughly 3,850 were accrued flying 747s.[8]

| Final tally of passenger nationalities | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

| 487 | 15 | 502 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 6 | 0 | 6[9] | |

| Total | 509 | 15 | 524 |

Passengers

The flight was around the Obon holiday period in Japan, when many Japanese people make yearly trips to their hometowns or resorts.[7] 299 of the passengers originated from Hyogo Prefecture and Osaka Prefecture in the Kansai region, making up 57% of the passengers.[9]

Around twenty-one non-Japanese boarded the flight.[10] By August 13, 1985, Geoffrey Tudor, a spokesman for Japan Airlines, stated that the list included four residents of Hong Kong, two each from Italy and the United States, and one each from West Germany and the United Kingdom.[11] Some foreigners had dual nationalities, and some of them were residents of Japan.[9]

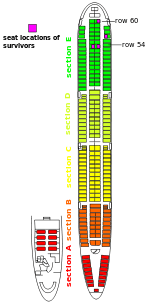

The four survivors, all female, were seated on the left side and toward the middle of seat rows 54–60, in the rear of the aircraft.[12]

The four survivors were:

- Yumi Ochiai (落合 由美 Ochiai Yumi), a 26-year old off-duty JAL flight attendant who was jammed between seats;

- Hiroko Yoshizaki (吉崎 博子 Yoshizaki Hiroko), a 34-year-old woman, and her 8-year-old daughter Mikiko Yoshizaki (吉崎 美紀子 Yoshizaki Mikiko), who were trapped in an intact section of the fuselage;

- Keiko Kawakami (川上 慶子 Kawakami Keiko) a 12-year-old girl, who was found from under the wreckage.[13] Air Disaster Volume 2 stated that she was wedged between branches in a tree.[14] Kawakami's parents and younger sister died in the crash, and she was the last survivor to be released from hospital. She was treated at the Matsue Red Cross Hospital (松江赤十字病院 Matsue Sekijūji Byōin) in Matsue, Shimane Prefecture before her release on Friday, November 22, 1985.[15]

Among the dead were singer Kyu Sakamoto; Koumo Soseke, the head of forestry for Osaka prefecture; and Japanese banker Akihisa Yukawa, the father of solo violinist Diana Yukawa.[16]

Sequence of events

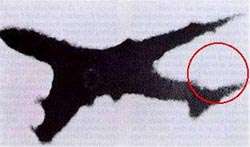

The aircraft landed at Haneda from New Chitose Airport at 4:50PM as JL514. After more than an hour on the ramp, Flight 123 pushed back from gate 18 at 6:04 p.m.[8] and took off from Runway 15L[3] at Haneda Airport in Ōta, Tokyo, Japan, at 6:12 p.m., twelve minutes behind schedule.[17] About 12 minutes after takeoff, at near cruising altitude over Sagami Bay, the aircraft's aft pressure bulkhead burst open due to a pre-existing defect stemming from a panel that had been incorrectly repaired after a tailstrike accident 7 years earlier. This caused an explosive decompression, causing pressurized air to rush out of the cabin, bringing down the ceiling around the rear lavatories. The compressed air then burst the unpressurized fuselage aft of the bulkhead unseating the vertical stabilizer and severing all four hydraulic lines. A photograph taken from the ground some time later confirmed that the vertical stabilizer was missing.[18] Loss of cabin pressure at high altitude caused a lack of oxygen throughout; emergency oxygen masks for passengers were deployed. Flight attendants, including one who was off-duty, administered oxygen to various passengers using hand-held tanks.[7]

The pilots set their transponder to broadcast a distress signal. Tokyo Area Control Center directed the aircraft to descend and follow emergency landing vectors. Because of control problems, Capt. Takahama requested a vector to Haneda, opposing ATC's suggestion to divert to Nagoya Airfield, knowing Haneda was ideally suited for a 747 in case of an emergency.[19]

Hydraulic fluid completely drained away through the rupture. With total loss of hydraulic control and non-functional control surfaces, plus the lack of stabilizing influence from the vertical stabilizer, the aircraft began up and down oscillation in a phugoid cycle. In response, the pilots exerted efforts to establish stability using differential engine thrust. Further measures to exert control, such as lowering the landing gear and flaps, interfered with control by throttle; the aircrew's ability to control the aircraft deteriorated.

Upon descending to 13,500 feet (4100 m), the pilots reported an uncontrollable aircraft. Heading over the Izu Peninsula the pilots turned towards the Pacific Ocean, then back towards the shore; they descended below 7,000 feet (2100 m) before returning to a climb. The aircraft reached 13,000 feet (4000 m) before entering an uncontrollable descent into the mountains and disappearing from radar at 6:56 p.m. at 6,800 feet (2100 m). In the final moments, the wing clipped a mountain ridge. During a subsequent rapid plunge, the plane then slammed into a second ridge, then flipped and landed on its back.[20] The aircraft's crash point, at an elevation of 1,565 metres (5,135 ft), is located in Sector 76, State Forest, 3577 Aza Hontani, Ouaza Narahara, Ueno Village, Tano District, Gunma Prefecture. The east-west ridge is about 2.5 kilometres (8,200 ft) north north west of Mount Mikuni.[21] Ed Magnuson of Time magazine said that the area where the aircraft crashed was referred to as the "Tibet" of Gunma Prefecture.[5]

The elapsed time from the bulkhead explosion to when the plane hit the mountain was estimated at 32 minutes – long enough for some passengers to write farewell messages to their families.[7][22] Subsequent simulator re-enactments with the mechanical failures suffered by the crashed plane failed to produce a better solution, or outcome; none of the four flight crews in the simulations kept the plane aloft for as long as the 32 minutes achieved by the actual crew.[7]

Delayed rescue operation

United States Air Force controllers at Yokota Air Base situated near the flight path of Flight 123 had been monitoring the distressed aircraft's calls for help. They maintained contact throughout the ordeal with Japanese flight control officials and made their landing strip available to the aeroplane. The Atsugi Naval Base also cleared their runway for JAL 123 after being alerted of the ordeal. After losing track on radar, a U.S. Air Force C-130 from the 345 TAS was asked to search for the missing plane. The C-130 crew was the first to spot the crash site 20 minutes after impact, while it was still daylight. The crew sent the location to Japanese authorities and radioed Yokota Air Base to alert them and directed a Huey helicopter from Yokota to the crash site. Rescue teams were assembled in preparation to lower Marines down for rescues by helicopter tow line. Despite American offers of assistance in locating and recovering the crashed plane, an order arrived, saying that U.S. personnel were to stand down and announcing that the Japan Self-Defense Forces were going to take care of it themselves and outside help was not necessary. To this day, it is unclear who issued the order denying U.S. forces permission to begin search and rescue missions.

Although a JSDF helicopter eventually spotted the wreck during the night, poor visibility and the difficult mountainous terrain prevented it from landing at the site. The pilot reported from the air that there were no signs of survivors. Based on this report, JSDF personnel on the ground did not set out to the site the night of the crash. Instead, they were dispatched to spend the night at a makeshift village erecting tents, constructing helicopter landing ramps and engaging in other preparations, all 63 kilometers (39.1 miles) from the wreck. Rescue teams did not set out for the crash site until the following morning. Medical staff later found bodies with injuries suggesting that individuals had survived the crash only to die from shock, exposure overnight in the mountains, or from injuries that, if tended to earlier, would not have been fatal.[14] One doctor said "If the discovery had come ten hours earlier, we could have found more survivors."[23]

Off-duty flight attendant Yumi Ochiai, one of the four survivors out of 524 passengers and crew, recounted from her hospital bed that she recalled bright lights and the sound of helicopter rotors shortly after she awoke amid the wreckage, and while she could hear screaming and moaning from other survivors, these sounds gradually died away during the night.[14]

Cause

The official cause of the crash according to the report published by Japan's Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission is as follows:

- The aircraft was involved in a tailstrike incident at Osaka International Airport seven years earlier as JAL Flight 115, which damaged the aircraft's rear pressure bulkhead.

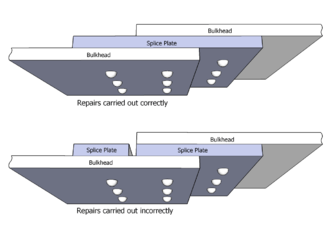

- The subsequent repair of the bulkhead did not conform to Boeing's approved repair methods.[24][25] The Boeing technicians fixing the aircraft used two separate splice plates, one with two rows of rivets and one with only one row when the procedure called for one continuous splice plate (essentially a patch or doubler plate) with three rows of rivets to reinforce the damaged bulkhead.[26] The incorrect repair reduced the part's resistance to metal fatigue to about 70% compared to the correctly executed repair. According to the Federal Aviation Administration, the one splice plate which was specified for the job was cut into two pieces parallel to the stress crack it was intended to reinforce, "to make it fit".[27] This negated the effectiveness of one of the rows of rivets. During the investigation, Boeing calculated that this incorrect installation would fail after approximately 10,000 pressurization cycles; the aircraft accomplished 12,318 successful flights from the time that the faulty repair was made to when the crash happened.

- When the bulkhead gave way, the resulting explosive decompression ruptured the lines of all four hydraulic systems and ejected the vertical stabilizer. With the aircraft's flight controls disabled, the aircraft became uncontrollable.

Aftermath and legacy

The Japanese public's confidence in Japan Airlines took a dramatic downturn in the wake of the disaster, with passenger numbers on domestic routes dropping by one-third. Rumors persisted that Boeing had admitted fault to cover up shortcomings in the airline's inspection procedures, thus protecting the reputation of a major customer.[14] In the months after the crash, domestic traffic decreased by as much as 25%. In 1986, for the first time in a decade, fewer passengers boarded JAL's overseas flights during the New Year period than the previous year. Some of them considered switching to All Nippon Airways as a safer alternative.[28]

JAL paid ¥780 million (7.6 million USD) to the victims' relatives in the form of "condolence money" without admitting liability. JAL president, Yasumoto Takagi (高木 養根), resigned. Hiroo Tominaga, a JAL maintenance manager, and Susumu Tajima, an engineer who had inspected and cleared the aircraft as flight-worthy, both killed themselves to apologize for the accident.[14][29][30]

In 2009, stairs with a handrail were installed to facilitate visitors' access to the crash site. Japan Transport Minister Seiji Maehara visited the site on August 12, 2010, to pray for the victims.[31]

In 2011, British academic Christopher Hood published a book, titled Dealing with Disaster in Japan: Responses to the Flight JL123 Crash, on the crash and its effect on Japanese society.[32][33]

Japan Airlines no longer uses flight number 123. After September 1, 1985, the flight was changed to Flight 127, now using either Boeing 767 or Boeing 777. Japan Air retired their last Boeing 747 on March 1, 2011, ending 41 years of service with the airliner.

Families of the victims, together with local volunteer groups, hold an annual memorial gathering every August 12 near the crash site in Gunma Prefecture.[34]

The crash also led to the 2006 opening of the Safety Promotion Center.[35][36] It is located in the Daini Sogo Building on the grounds of Haneda Airport.[37] This center was created for training purposes to alert employees of the importance of airline safety and their personal responsibility to ensure safety. The center, which has displays regarding aviation safety, the history of the crash, and selected pieces of the aircraft and passenger effects (including handwritten farewell notes), is also open to the public by appointment made one day prior to the visit.

The captain's daughter, Yoko Takahama, who was a high school student at the time of the crash, went on to become a flight attendant for Japan Airlines.[38]

In popular culture

- Japan Airlines Flight 123 is featured in the TV series Mayday (called Air Emergency or Air Disasters in the U.S. and Air Crash Investigation in other countries outside Canada) 3rd-season episode 3 "Out of Control (2005) (Japanese title "Osutaka-no-One (御巣鷹の尾根)")". This episode was also shown as Season 6 Episode 3 on the Smithsonian Channel.[39] The crash also featured in the second series of Aircrash Confidential in programme 5 about 'Poor Maintenance' first aired on March 15, 2012 on the Discovery Channel in the United Kingdom.[40][41] The Seconds From Disaster episode "Terrified over Tokyo" featured the accident in December 2012.

- Climber's High was released in 2008. This film is based on the novel by Hideo Yokoyama. The novel and film revolve around the reporting of the crash at the fictional Kita-Kanto Shimbun. Yokoyama was a journalist at the Jōmō Shimbun at the time of the crash.

- In 2009, Shizumanu Taiyō, starring Ken Watanabe, was released to national distribution in Japan. The film, which does not mention JAL by name, instead using the name "National Airlines", gives a semi-fictional account of internal airline corporate disputes and politics surrounding the crash. JAL did not cooperate with the making of the film.[42] JAL criticized the film, saying that it "not only damages public trust in the company but could lead to a loss of customers."[43]

- The cockpit voice recording of the incident also became part of the script of a play called Charlie Victor Romeo.

- A fragment of the flight recorder of the Japanese Boeing 747 disaster is recorded on the "0-Track" of the German band Rammstein on their 2004 album Reise, Reise.

See also

- China Airlines Flight 611

- British European Airways Flight 706

- List of aircraft accidents and incidents resulting in at least 50 fatalities

These are 2 accidents that lost flight controls just like JAL123:

References

Notes

- 1 2 "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 747SR-46 JA8119 Ueno." Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- ↑ "100 worst aviation accidents".

- 1 2 Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission. "2. Factual information." Aircraft Accident Investigation Report – Japan Air Lines flight 123 2.1.1 (1987): 6. Print.

- ↑ "JAL123便墜落事故28年目の記録". Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- 1 2 Magnuson, Ed. "Last Minutes of JAL 123." TIME. 9171,1074738-1,00.html 1. Retrieved October 25, 2007.

- ↑ "Pictures of the three pilots". Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cineflix, Stone City Films (2006). Mayday: Out of Control (documentary TV series).

- 1 2 http://www.mlit.go.jp/jtsb/eng-air_report/JA8119.pdf

- 1 2 3 Hood, Dealing with Disaster in Japan, p. 45.

- ↑ "524 killed in worst single air disaster." The Guardian.

- ↑ Moosa, Eugene. "Jet Crash Kills Over 500 In Mountains of Japan." Associated Press at The Schenectady Gazette. Tuesday Morning August 13, 1985. First Edition. Volume 91 (XCI) No. 271. Front Page (p. 5?). Retrieved from Google News (1 of 2) on August 24, 2013. "JAL spokesman Geoffrey Tudor said two Americans were on the passenger list." and "JAL released a passenger list that included 21 non-Japanese names, and Tudor said there were two Americans, two Italians, one Briton, one West German, and four Chinese residents of Hong Kong"

- ↑ "Aircraft Accident Investigation Report Japan Air Lines Co., Ltd. Boeing 747 SR-100, JA8119 Gunma Prefecture, Japan August 12, 1985." 22 (33/332). Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ↑ Kawamura, Kazuo (河村 一男 Kawamura Kazuo)著、『日航機墜落』. ISBN 4872574486, 9784872574487. p. 169. See Google Books entry イースト・プレス:余裕の出たレンジャーは、他に生存者がいないかと、さらに周りを捜した。最後が中学少女であった。遺体を叩いて反応をみたりしているうちに、女性乗務員から沢寄り二メートルほどのところの遺体のあいだから、逆立ちをしているような格好で両足をばたつかせているのが見つかった。「僕、大丈夫か」と声をかけ、上にかぶさっている遺体や破片を取り除くと、中が空洞になっていて顔と左足が見えた。男の子とまちがえたようである。「痛いところはあるか」と聞くと、左足を開いてふくらはぎの傷をみせる仕草をした。右肘を挟まれており、すぐには引き出せなかった。: Rescues searched outskirts to find other survivors. They discovered a junior high student girl finally. When they were watching reactions of bodies by clapping them, they found moving legs as if doing a headstand. "Are you all right!" A rescue called out and removed bodies and wreckages covered it. Then he found a face and left leg. He took the person for a boy. "Do you have any other pain?" he asked. The girl moved her left leg and showed him a wound. Rescues could not relieve her immediately because her right elbow was sandwiched.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Macarthur Job, Air Disaster Volume 2, Aerospace Publications, 1996, ISBN 1-875671-19-6: pp.136–153

- ↑ "Survivor of JAL Crash Goes Home." Los Angeles Times. November 24, 1985. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ↑ Betti, Leeroy. "Looking up so tears won't fall." The Japan Times. Sunday November 26, 2000. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- ↑ Magnuson, Ed. "Last Minutes of JAL 123." TIME. 2.

- ↑ "Special Report: Japan Airlines Flight 123". AirDisaster.Com. August 12, 1985. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ↑ "The Internet Movie Database: Mayday – Out Of Control (Season 3, Episode 3)". The Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ Aircraft Accident Investigation Report – Japan Air Lines flight 123 2.1.1 (1987): 8. Print.

- ↑ "Aircraft Accident Investigation Report Japan Air Lines Co., Ltd. Boeing 747 SR-100, JA8119 Gunma Prefecture, Japan August 12, 1985." 8 (19/332). Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ↑ Smolowe, Jill, Jerry Hanafin, and Steven Holmes. "Disasters, Never a Year So Bad." TIME. Monday September 2, 1985. 3. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- ↑ "Last Minutes of JAL 123", Time, p.5. Retrieved October 25, 2007.

- ↑ Witkin, Richard. "Clues are Found in Japan Air Crash: Evidence Reported of Faulty Repairs That Could Have Led to Damage to Tail." New York Times. (September 6, 1985), A7.

- ↑ Horikoshi,Toyohiro. "U.S. leaked crucial Boeing repair flaw that led to 1985 JAL jet crash: ex-officials." Japan Times - Kyodo. (August 11, 2015).

- ↑ "Case Details > Crash of Japan Airlines B-747 at Mt. Osutaka". Sozogaku.com. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Applying Lessons Learned from Accidents, Air Board findings", FAA. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ↑ Andrew Horvat, "United's Welcome in Japan Less Than Warm", Los Angeles Times February 28, 1986

- ↑ New York Times "J.A.L. Official Dies, Apparently a Suicide", September 22, 1985

- ↑ The Associated Press "ENGINEER WHO INSPECTED PLANE BEFORE CRASH COMMITS SUICIDE", March 18, 1987

- ↑ Mainichi News http://mdn.mainichi.jp/mdnnews/news/20100812p2g00m0dm004000c.html[]

- ↑ Hollingworth, William (Kyodo News), "British academic to write account of 1985 JAL crash", Japan Times, July 22, 2007, p. 17.

- ↑ Dealing with Disaster in Japan: Responses to the Flight JL123 Crash (Routledge Official Website). Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ↑ "日航機事故28年、遺族ら灯籠流し 墜落現場の麓で". 共同通信. August 11, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Why Japan Airlines Opened a Museum to Remember a Crash", The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 2, 2007.

- ↑ Black Box as a Safety Device, The New York Times. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Safety Promotion Center." Japan Airlines. Retrieved August 18, 2010. Archived May 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "日航機墜落30年 機長の長女はいま…". livedoor News. 日テレNEWS24. August 12, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Air Disasters: Out of Control" Smithsonian Channel website

- ↑ Aircrash Confidential web page Archived November 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Discovery Channel TV Listings for March 15, 2012". Discoveryuk.com. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ↑ Schilling, Mark, "Japanese films reach for sky, but it's a good bet JAL wishes this one had stayed grounded", Japan Times, October 23, 2009.

- ↑ Jiji, "JAL hits film's disparaging parallels", Japan Times, November 4, 2009, p. 1.

Bibliography

- Hood, Christopher P., Dealing with Disaster in Japan: Responses to the Flight JL123 Crash, (2011), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415456623 (hard back), ISBN 978-0415705998 (paper back). eBook also available.

- Hood, Christopher P., Osutaka: A Chronicle of Loss In the World's Largest Single Plane Crash, (2014), ISBN 978-1-291-97619-9 (eBook), ISBN 978-1-291-97620-5 (paper back).

Further reading

- "Crash: Japanese took 12 hours to reach site." (Archive) Pacific Stars and Stripes. Sunday August 27, 1995. p. 6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Japan Airlines Flight 123. |

- Aircraft Accident Report, English translation – Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission (East Asian fonts may need to be installed)

- (Japanese) Aircraft Accident Report – Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission

- Learning from the Past Japan Airlines

- Details of the book Dealing with Disaster in Japan: Responses to the Flight JL123 Crash

- Details of the book Osutaka: A Chronicle of Loss in the World's Largest Single Plane Crash

- Crash of Japan Airlines B-747 at Mt. Osutaka

- JAL123 CVR (cockpit voice recorder) transcript

- Christopher Hood's Research about JL123

- JAL123 CVR (cockpit voice recorder) audio of the final moments of flight

- Charlie-Victor-Romeo – a play which features this aircraft accident

- The 20th Anniversary of Japan Air 123 (BBC)

- The record of JAL123 (Japanese with English place names)

- Japan Airlines Flight 123 Accident (Aug 12, 1985) – Cockpit Voice Recorder [English Subbed] on YouTube

- CVR (cockpit voice recorder) audio of the final moments of flight on YouTube

- JAL123 Tokyo control communications records on YouTube

- Japan Airlines Flight 123 - Out of Control. National Geographic Documentary on YouTube

- Planesafe.org: JAL123

- Narratives on the World's Worst Plane Crash: Flight JL123 in Print and on Screen (Archive) (by Hood, C.P. (2009), Research Seminar Paper, Ref No.7, Cardiff Crimes Narrative Network, Cardiff University – http://www.cf.ac.uk/chri/research/cnic/)

- The New York Times: J.A.L.'s Post-Crash Troubles