Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian Democrats | |

|---|---|

| Historical leaders |

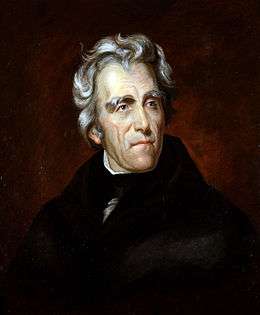

Andrew Jackson Martin Van Buren James K. Polk Thomas Hart Benton Stephen A. Douglas |

| Founded | 1828 |

| Dissolved | 1854 |

| Ideology |

Populism Agrarianism Spoils system Manifest destiny |

| National affiliation | Democratic Party |

Jacksonian democracy is the political movement during the Second Party System toward greater democracy for the common man symbolized by American politician Andrew Jackson and his supporters. The Jacksonian Era lasted roughly from Jackson's 1828 election as president until the slavery issue became dominant after 1854 and the American Civil War dramatically reshaped American politics as the Third Party System emerged. Jackson's policies followed the era of Jeffersonian democracy which dominated the previous political era. When the Democratic-Republican Party of the Jeffersonians became factionalized in the 1820s, Jackson's supporters began to form the modern Democratic Party. They fought the rival Adams and Anti-Jacksonian factions, which by 1834 emerged as the Whigs.

More broadly, the term refers to the era of the Second Party System (mid-1830s–1854) characterized by a democratic spirit. It can be contrasted with the characteristics of Jeffersonian democracy. Jackson's equal political policy became known as "Jacksonian Democracy", subsequent to ending what he termed a "monopoly" of government by elites. Jeffersonians opposed inherited elites but favored educated men while the Jacksonians gave little weight to education. The Whigs were the inheritors of Jeffersonian Democracy in terms of promoting schools and colleges.[1] Even before the Jacksonian era began, suffrage had been extended to a majority of white male adult citizens, a result the Jacksonians celebrated.[2]

In contrast to the Jeffersonian era, Jacksonian democracy promoted the strength of the presidency and executive branch at the expense of Congress, while also seeking to broaden the public's participation in government. The Jacksonians demanded elected (not appointed) judges and rewrote many state constitutions to reflect the new values. In national terms they favored geographical expansion, justifying it in terms of Manifest Destiny. There was usually a consensus among both Jacksonians and Whigs that battles over slavery should be avoided.

Jackson's expansion of democracy was largely limited to Americans of European descent, and voting rights were extended to adult white males only. There was little or no progress for African-Americans and Native Americans (in some cases regress).[3]

Jackson's biographer Robert V. Remini argues that Jacksonian Democracy:

- stretches the concept of democracy about as far as it can go and still remain workable....As such it has inspired much of the dynamic and dramatic events of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in American history—Populism, Progressivism, the New and Fair Deals, and the programs of the New Frontier and Great Society.[4]

The philosophy

Jacksonian Democracy was built on the following general principles:[5]

- Expanded Suffrage

- The Jacksonians believed that voting rights should be extended to all white men. By the end of the 1820s, attitudes and state laws had shifted in favor of universal white male suffrage,[6] and by 1856 all requirements to own property and nearly all requirements to pay taxes had been dropped.[7][8]

- Manifest Destiny

- This was the belief that white Americans had a destiny to settle the American West and to expand control from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific and that the West should be settled by yeoman farmers. However, the Free Soil Jacksonians, notably Martin Van Buren, argued for limitations on slavery in the new areas to enable the poor white man to flourish; they split with the main party briefly in 1848. The Whigs generally opposed Manifest Destiny and expansion, saying the nation should build up its cities.[9]

- Patronage

- Also known as the spoils system, patronage was the policy of placing political supporters into appointed offices. Many Jacksonians held the view that rotating political appointees in and out of office was not only the right but also the duty of winners in political contests. Patronage was theorized to be good because it would encourage political participation by the common man and because it would make a politician more accountable for poor government service by his appointees. Jacksonians also held that long tenure in the civil service was corrupting, so civil servants should be rotated out of office at regular intervals. However, it often led to the hiring of incompetent and sometimes corrupt officials due to the emphasis on party loyalty above any other qualifications.[10]

- Strict Constructionism

- Like the Jeffersonians who strongly believed in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, Jacksonians initially favored a federal government of limited powers. Jackson said that he would guard against "all encroachments upon the legitimate sphere of State sovereignty." However, he was not a states' rights extremist; indeed, the Nullification Crisis would find Jackson fighting against what he perceived as state encroachments on the proper sphere of federal influence. This position was one basis for the Jacksonians' opposition to the Second Bank of the United States. As the Jacksonians consolidated power, they more often advocated expanding federal power, presidential power in particular.[11]

- Laissez-faire Economics

- Complementing a strict construction of the Constitution, the Jacksonians generally favored a hands-off approach to the economy, as opposed to the Whig program sponsoring modernization, railroads, banking, and economic growth.[12][13] The chief spokesman amongst laissez-faire advocates was William Leggett of the Locofocos in New York City.[14][15]

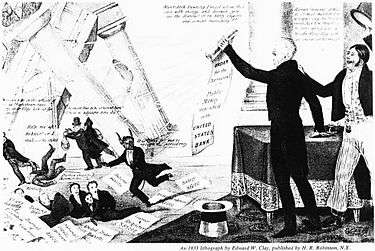

- Banking

- In particular, the Jacksonians opposed government-granted monopolies to banks, especially the national bank, a central bank known as the Second Bank of the United States. Jackson said, "The bank is trying to kill me, but I will kill it!" And he did so.[16] The Whigs, who strongly supported the Bank, were led by Daniel Webster and Nicholas Biddle, the bank chairman.[17] Jackson himself was opposed to all banks because he believed they were devices to cheat common people; he and many followers believed that only gold and silver should be used to back currency, rather than the integrity of a bank.

Election by the "Common Man"

An important movement in the period from 1800 to 1830—before the Jacksonians were organized—was the expansion of the right to vote toward including all white men.[18] Older states with property restrictions dropped them; all but Rhode Island, Virginia and North Carolina by the mid 1820s. No new states had property qualifications although three had adopted tax-paying qualifications – Ohio, Louisiana, and Mississippi, of which only in Louisiana were these significant and long lasting.[19] The process was peaceful, and widely supported, except in the state of Rhode Island. In Rhode Island, the Dorr Rebellion of the 1840s demonstrated that the demand for equal suffrage was broad and strong, although the subsequent reform included a significant property requirement for anyone resident but born outside of the United States. Free black men, however, lost voting rights in several states during this period.[20]

The fact that a man was now legally allowed to vote did not necessarily mean he routinely voted. He had to be pulled to the polls, which became the most important role of the local parties. They systematically sought out potential voters and brought them to the polls. Voter turnout soared during the Second Party System, reaching about 80% of the adult white men by 1840.[21] Tax-paying qualifications remained in only five states by 1860 – Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and North Carolina.[22]

The Anti-Masonic Party, an opponent of Jackson, introduced the national nominating conventions to select a party's presidential and vice presidential candidates, allowing more voter input.[23]

Factions 1824–32

The period 1824–32 was politically chaotic. The Federalist Party and the First Party System were dead,and with no effective opposition, the old Democratic-Republican Party withered away. Every state had numerous political factions, but they did not cross state lines. Political coalitions formed and dissolved, and politicians moved in and out of alliances.[24]

Most former Republicans supported Jackson; others, such as Henry Clay, opposed him. Most former Federalists, such as Daniel Webster, opposed Jackson, although some like James Buchanan supported him. In 1828, John Quincy Adams pulled together a network of factions called the National Republicans, but he was defeated by Jackson. By the late 1830s, the Jacksonian Democrats and the Whigs politically battled it out nationally and in every state.[25]

The new Democratic Party

Jacksonian Democracy

The spirit of Jacksonian Democracy animated the party from the early 1830s to the 1850s, shaping the Second Party System, with the Whig Party the main opposition. The new Democratic Party became a coalition of farmers, city-dwelling laborers, and Irish Catholics.[26]

The new party was pulled together by Martin Van Buren in 1828 as Andrew Jackson crusaded against the corruption of President John Quincy Adams. The new party (which did not get the name "Democrats" until 1834) swept to a landslide. As Norton et al. explain regarding 1828:

- Jacksonians believed the people's will had finally prevailed. Through a lavishly financed coalition of state parties, political leaders, and newspaper editors, a popular movement had elected the president. The Democrats became the nation's first well-organized national party.[27]

The platforms, speeches, and editorials were founded upon a broad consensus among Democrats. As Norton et al. explain:

- The Democrats represented a wide range of views but shared a fundamental commitment to the Jeffersonian concept of an agrarian society. They viewed a central government as the enemy of individual liberty and they believed that government intervention in the economy benefited special-interest groups and created corporate monopolies that favored the rich. They sought to restore the independence of the individual--the artisan and the ordinary farmer--by ending federal support of banks and corporations and restricting the use of paper currency.[28]

Jackson vetoed more legislation than all previous presidents combined. The long-term effect was to create the modern strong presidency.[29] Jackson and his supporters also opposed reform as a movement. Reformers eager to turn their programs into legislation called for a more active government. But Democrats tended to oppose programs like educational reform and the establishment of a public education system. They believed, for instance, that public schools restricted individual liberty by interfering with parental responsibility and undermined freedom of religion by replacing church schools.

Jackson supported white supremacy, as did nearly every major politician of the day. He looked at the Indian question in terms of military and legal policy, not as a problem due to their race.[30] Indeed, in 1813 he adopted and treated as his own son a three-year-old Indian orphan—seeing in him a fellow orphan that was "so much like myself I feel an unusual sympathy for him."[31] In legal terms, when it became a matter of state sovereignty versus tribal sovereignty, he went with the states and moved the Indians to fresh lands with no white rivals in what became Oklahoma.[32]

Reforms

Jackson fulfilled his promise of broadening the influence of the citizenry in government, although not without vehement controversy over his methods.[33]

Jacksonian policies included ending the bank of the United States, expanding westward, and removing American Indians from the Southeast. Jackson was denounced as a tyrant by opponents on both ends of the political spectrum such as Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. This led to the rise of the Whig Party.

Jackson created a spoils system to clear out elected officials in government of an opposing party and replace them with his supporters as a reward for their electioneering. With Congress controlled by his enemies, Jackson relied heavily on the power of the veto to block their moves.

One of the most important of these was the Maysville Road veto in 1830. A part of Clay's American System, the bill would have allowed for federal funding of a project to construct a road linking Lexington and the Ohio River, the entirety of which would be in the state of Kentucky. His primary objection was based on the local nature of the project. He argued it was not the Federal government's job to fund projects of such a local nature, and or those lacking a connection to the nation as a whole. The debates in Congress reflected two competing visions of federalism. The Jacksonians saw the union strictly as the cooperative aggregation of the individual states, while the Whigs saw the entire nation as a distinct entity.[34]

Jacksonian Presidents

In addition to Jackson, his second vice president and one of the key organizational leaders of the Jacksonian Democratic Party, Martin Van Buren, served as president. Van Buren was defeated in the next election by William H. Harrison. Harrison died just 30 days into his term, and his vice president, John Tyler, quickly reached accommodation with the Jacksonians. Tyler was then succeeded by James K. Polk, a Jacksonian who won the election of 1844 with Jackson's endorsement.[35] Franklin Pierce had been a supporter of Jackson as well. James Buchanan served in Jackson's administration as Minister to Russia and as Polk's Secretary of State, but he did not pursue Jacksonian policies. Finally, Andrew Johnson, who had been a strong supporter of Jackson, became president following the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865.

See also

- Andrew Jackson presidential campaign, 1828

- Voting rights in the United States

- Democratic Party (United States)

- Jeffersonian democracy

Notes

- ↑ Groen, Mark (2008). "The Whig Party and the Rise of Common Schools, 1837–1854". American Educational History Journal. 35 (2): 251–260.

- ↑ Engerman, pp. 15, 36. "These figures suggest that by 1820 more than half of adult white males were casting votes, except in those states that still retained property requirements or substantial tax requirements for the franchise – Virginia, Rhode Island (the two states that maintained property restrictions through 1840), and New York as well as Louisiana."

- ↑ Warren, Mark E. (1999). Democracy and Trust. Cambridge University Press. pp. 166–. ISBN 9780521646871.

- ↑ Robert V. Remini (2011). The Life of Andrew Jackson. HarperCollins. p. 307.

- ↑ Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Age of Jackson (1945)

- ↑ Engerman, p. 14. "Property- or tax-based qualifications were most strongly entrenched in the original thirteen states, and dramatic political battles took place at a series of prominent state constitutional conventions held during the late 1810s and 1820s."

- ↑ Engerman, pp. 16, 35. "By 1840, only three states retained a property qualification, North Carolina (for some state-wide offices only), Rhode Island, and Virginia. In 1856 North Carolina was the last state to end the practice. Tax-paying qualifications were also gone in all but a few states by the Civil War, but they survived into the 20th century in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island."

- ↑ Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (2nd ed. 2009) p 29

- ↑ David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, Manifest Destiny (Greenwood Press, 2003).

- ↑ M. Ostrogorski, Democracy and the Party System in the United States (1910)

- ↑ Forrest McDonald, States' Rights and the Union: Imperium in Imperio, 1776-1876 (2002) pp 97-120

- ↑ William Trimble, "The social philosophy of the Loco-Foco democracy." American Journal of Sociology 26.6 (1921): 705-715. in JSTOR

- ↑ Louis Hartz, Economic Policy and Democratic Thought: Pennsylvania, 1776-1860 (1948)

- ↑ Richard Hofstadter, "William Leggett, Spokesman of Jacksonian Democracy." Political Science Quarterly 58.4 (1943): 581-594. in JSTOR

- ↑ Lawrence H. White, "William Leggett: Jacksonian editorialist as classical liberal political economist." History of Political Economy 18.2 (1986): 307-324.

- ↑ Melvin I. Urofsky (2000). The American Presidents: Critical Essays. Taylor & Francis. p. 106.

- ↑ Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America, From the Revolution to the Civil War (1957)

- ↑ Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (2009) ch 2

- ↑ Engerman, p. 8–9

- ↑ Murrin, John M.; Johnson, Paul E.; McPherson, James M.; Fahs, Alice; Gerstle, Gary (2012). Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People (6th ed.). Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-495-90499-1.

- ↑ William G. Shade, "The Second Party System". in Paul Kleppner, et al. Evolution of American Electoral Systems (1983) pp 77-111

- ↑ Engerman, p. 35. Table 1

- ↑ William Preston Vaughn, The Anti-Masonic Party in the United States: 1826-1843 (2009)

- ↑ Richard P. McCormick, The Second American Party System: Party Formation in the Jacksonian Era (1966).

- ↑ Michael F. Holt, Political Parties and American Political Development: From the Age of Jackson to the Age of Lincoln (1992)

- ↑ Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (2005)

- ↑ Mary Beth Norton; et al. (2014). A People and a Nation, Volume I: to 1877. Cengage Learning. p. 348.

- ↑ Mary Beth Norton; et al. (2007). A People and a Nation: A History of the United States, Volume I: To 1877. Cengage Learning. p. 327.

- ↑ John Yoo, "Andrew Jackson and Presidential Power." Charleston Law Review 2 (2007): 521+ online.

- ↑ Prucha, Francis Paul (1969). "Andrew Jackson's Indian policy: a reassessment". Journal of American History. 56 (3): 527–539. JSTOR 1904204.

- ↑ Michael Paul Rogin (1991). Fathers and Children: Andrew Jackson and the Subjugation of the American Indian. Transaction Publishers. p. 189.

- ↑ Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, The Cherokee removal: a brief history with documents (2005.)

- ↑ Donald B. Cole, The Presidency of Andrew Jackson (1993)

- ↑ Wulf, Naomi (2001). "'The Greatest General Good': Road Construction, National Interest, and Federal Funding in Jacksonian America". European Contributions to American Studies. 47: 53–72.

- ↑ "James K. Polk: Life in Brief". Miller Center. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

References and bibliography

- Adams, Sean Patrick, ed. A Companion to the Era of Andrew Jackson (2013). table of contents

- Altschuler, Glenn C.; Blumin, Stuart M. (1997). "Limits of Political Engagement in Antebellum America: A New Look at the Golden Age of Participatory Democracy". Journal of American History. Organization of American Historians. 84 (3): 855–885 [p. 878–879]. doi:10.2307/2953083. JSTOR 2953083.

- Baker, Jean (1983). Affairs of Party: The Political Culture of Northern Democrats in the Mid-Nineteenth Century. Bronx, NY: Fordham University Press. ISBN 0-585-12533-3.

- Benson, Lee (1961). The Concept of Jacksonian Democracy: New York as a Test Case. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 0-691-00572-9. OCLC 21378753.

- Bugg, James L., Jr. (1952). Jacksonian Democracy: Myth or Reality?. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Short essays.

- Cave, Alfred A. (1964). Jacksonian Democracy and the Historians. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press.

- Cole, Donald B. (1984). Martin Van Buren And The American Political System. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04715-4.

- Cole, Donald B. (1970). Jacksonian Democracy in New Hampshire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-46990-9. Uses quantitative electoral data.

- Cheathem, Mark R. and Terry Corps, eds. Historical Dictionary of the Jacksonian Era and Manifest Destiny (2nd ed. 2016), 544pp

- Engerman, Stanley L.; Sokoloff, Kenneth L. (2005). "The Evolution of Suffrage Institutions in the New World" (PDF): 14–16.

- Formisano, Ronald P. (1971). The Birth of Mass Political Parties: Michigan, 1827-1861. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04605-0. Uses quantitative electoral data.

- Formisano, Ronald P. (1983). The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s-1840s. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503124-5. Uses quantitative electoral data.

- Formisano, Ronald P. (1999). "The 'Party Period' Revisited". Journal of American History. Organization of American Historians. 86 (1): 93–120. doi:10.2307/2567408. JSTOR 2567408.

- Formisano, Ronald P. (1969). "Political Character, Antipartyism, and the Second Party System". American Quarterly. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 21 (4): 683–709. doi:10.2307/2711603. JSTOR 2711603.

- Formisano, Ronald P. (1974). "Deferential-Participant Politics: The Early Republic's Political Culture, 1789-1840". American Political Science Review. American Political Science Association. 68 (2): 473–487. doi:10.2307/1959497. JSTOR 1959497.

- Hammond, Bray (1958). Andrew Jackson's Battle with the "Money Power". Chapter 8, an excerpt from his Pulitzer-prize-winning Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (1954).

- Hofstadter, Richard (1948). The American Political Tradition. Chapter on AJ.

- Hofstadter, Richard. "William Leggett: Spokesman of Jacksonian Democracy." Political Science Quarterly 58#4 (December 1943): 581-94. in JSTOR

- Hofstadter, Richard (1969). The Idea of a Party System: The Rise of Legitimate Opposition in the United States, 1780-1840.

- Holt, Michael F. (1999). The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505544-6.

- Holt, Michael F. (1992). Political Parties and American Political Development: From the Age of Jackson to the Age of Lincoln. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1728-5.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (Oxford History of the United States) (2009), Pulitzer Prize; surveys era from ant-Jacksonain perspective

- Howe, Daniel Walker (1991). "The Evangelical Movement and Political Culture during the Second Party System". Journal of American History. Organization of American Historians. 77 (4): 1216–1239. doi:10.2307/2078260. JSTOR 2078260.

- Kohl, Lawrence Frederick (1989). The Politics of Individualism: Parties and the American Character in the Jacksonian Era. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505374-5.

- Kruman, Marc W. (1992). "The Second American Party System and the Transformation of Revolutionary Republicanism". Journal of the Early Republic. Society for Historians of the Early American Republic. 12 (4): 509–537. doi:10.2307/3123876. JSTOR 3123876.

- Lane, Carl. "The Elimination of the National Debt in 1835 and the Meaning Of Jacksonian Democracy." Essays in Economic & Business History 25 (2007). online

- McCormick, Richard L. (1986). The Party Period and Public Policy: American Politics from the Age of Jackson to the Progressive Era. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503860-6.

- McCormick, Richard P. (1966). The Second American Party System: Party Formation in the Jacksonian Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. Influential state-by-state study.

- McKnight, Brian D., and James S. Humphreys, eds. The Age of Andrew Jackson: Interpreting American History (Kent State University Press; 2012) 156 pages; historiography

- Mayo, Edward L. (1979). "Republicanism, Antipartyism, and Jacksonian Party Politics: A View from the Nation's Capitol". American Quarterly. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 31 (1): 3–20. doi:10.2307/2712484. JSTOR 2712484.

- Marshall, Lynn (1967). "The Strange Stillbirth of the Whig Party". American Historical Review. American Historical Association. 72 (2): 445–468. doi:10.2307/1859236. JSTOR 1859236.

- Myers, Marvin (1957). The Jacksonian Persuasion: Politics and Belief. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Pessen, Edward (1978). Jacksonian America: Society, Personality, and Politics.

- Pessen, Edward (1977). The Many-Faceted Jacksonian Era: New Interpretations. Important scholarly articles.

- Remini, Robert V. (1998). The Life of Andrew Jackson. Abridgment of Remini's 3-volume biography.

- Remini, Robert V. (1959). Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party.

- Rowland, Thomas J. Franklin B. Pierce: The Twilight of Jacksonian Democracy (Nova Science Publisher's, 2012).

- Sellers, Charles (1991). The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815-1846. Influential reinterpretation

- Shade, William G. "Politics and Parties in Jacksonian America," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography Vol. 110, No. 4 (Oct., 1986), pp. 483–507 online

- Shade, William G. (1983). "The Second Party System". In Kleppner, Paul; et al. Evolution of American Electoral Systems. Uses quantitative electoral data.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr (1945). The Age of Jackson. Boston: Little, Brown & Company. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for History.

- Sellers, Charles (1958). "Andrew Jackson Versus the Historians". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. Organization of American Historians. 44 (4): 615–634. doi:10.2307/1886599. JSTOR 1886599.

- Sharp, James Roger (1970). The Jacksonians Versus the Banks: Politics in the States after the Panic of 1837. Uses quantitative electoral data.

- Silbey, Joel H. (1991). The American Political Nation, 1838-1893.

- Silbey, Joel H. (1973). Political Ideology and Voting Behavior in the Age of Jackson.

- Simeone, James. "Reassessing Jacksonian Political Culture: William Leggett’s Egalitarianism." American Political Thought 4#3 (2015): 359-390. in JSTOR

- Syrett, Harold C. (1953). Andrew Jackson: His Contribution to the American Tradition.

- Taylor, George Rogers (1949). Jackson Versus Biddle: The Struggle over the Second Bank of the United States. Excerpts from primary and secondary sources.

- Van Deusen, Glyndon G. (1963). The Jacksonian Era: 1828-1848. Standard scholarly survey.

- Wallace, Michael (1968). "Changing Concepts of Party in the United States: New York, 1815-1828". American Historical Review. American Historical Association. 74 (2): 453–491. doi:10.2307/1853673. JSTOR 1853673.

- Ward, John William (1962). Andrew Jackson, Symbol for an Age.

- Wellman, Judith. Grassroots Reform in the Burned-over District of Upstate New York: Religion, Abolitionism, and Democracy (Routledge, 2014).

- Wilentz, Sean (1982). "On Class and Politics in Jacksonian America". Reviews in American History. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 10 (4): 45–63. doi:10.2307/2701818. JSTOR 2701818.

- Wilentz, Sean (2005). The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. Highly detailed scholarly synthesis.

- Wilson, Major L. (1974). Space, Time, and Freedom: The Quest for Nationality and the Irrepressible Conflict, 1815-1861. Intellectual history of Whigs and Democrats.

Primary sources

- Blau, Joseph L., ed. Social Theories of Jacksonian Democracy: Representative Writings of the Period 1825-1850 (1954) online edition

- Eaton, Clement ed. The Leaven of Democracy: The Growth of the Democratic Spirit in the Time of Jackson (1963) online edition

External links

- American Political History Online

- Second Party System 1824-1860 short essays by scholar Michael Holt

- Tales of the Early Republic collection of texts and encyclopedia entries on Jacksonian Era, by Hal Morris

- Register of Debates in Congress, 1824-37; complete text; searchable

- Daniel Webster

- documents on Indian removal 1831-33

- war with Mexico: links

- Hammond, The history of political parties in the state of New-York(1850) history to 1840 from MOA Michigan

- Triumph of Nationalism 1815-1850 study guides & teaching tools

.svg.png)