International Juridical Association

Disambiguation: There is another International Juridical Association in Rome, an European environmental law think tank.

| Predecessor | International Labor Defense, International Red Aid |

|---|---|

| Successor | National Lawyers Guild |

| Formation | 1931 |

| Founder | Carol Weiss King |

| Founded at | New York City |

| Extinction | December 1942 |

| Headquarters | New York City |

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 40°44′14″N 73°59′35″W / 40.737222°N 73.993143°WCoordinates: 40°44′14″N 73°59′35″W / 40.737222°N 73.993143°W |

| Services | Legal |

Official language | English |

Executive Director | Isadore Polier |

Secretary | Carol Weiss King |

| Carol Weiss King, Osmond K. Fraenkel, Joseph Brodsky, Roy Wilkins, Paul F. Brissenden, Jerome Frank, Karl Llewelyn, Charles Erskine Scott Wood, Floyd Dell, Yetta Land | |

Key people | Joseph Kovner, editor |

Main organ | International Juridical Association Bulletin |

Parent organization | International Juridical Association (Germany) |

The International Juridical Association (IJA) was an association of socially minded American lawyers, established by Carol Weiss King[1] and considered by the U.S. federal government (in the form of the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee or HUAC) as "another early (communist) front for lawyers. The principle concern about the IJA (and its successor group, the National Lawyers Guild or NLG) was that it "constituted itself an agent of a foreign principal hostile to the interests of the United States."[2][3][4]

History

Background

HUAC's account of the IJA traced back to 1922, when the Communist International established the International Red Aid (Russian acronym "MOPR") to:

"Render material and moral aid to the imprisoned victims of capitalism"

–Resolutions and Theses of the Fourth Congress of the Communist International (London: Communist Party of Great Britain, 1922) p. 87[2]

HUAC's translation: International Red Aid (MOPR) served to protect Comintern ("subversive") agents "whenever they ran into difficulties with the law of the various countries in which they were operating."[2]

In 1925, MOPR had established an American section known as the International Labor Defense (ILD). The ILD functioned until 1946, when it merged into the Civil Rights Congress (CRC), deemed a "new subversive organization" by HUAC.[2]

Establishment

According to HUAC, the International Juridical Association (IJA) formed in 1931 and "cooperated closely" with the ILD.[2]

According to a biography by Ann Fagan Ginger, the IJA was the brainchild of Carol Weiss King. As Ginger recounts, King decided to take "a trip to Europe" and happened to choose Russia thanks to an ad for "12 thrilling days in the U.S.S.R"[4] (The source happened to appear in the communist literary magazine New Masses. Ginger wrongly cites summer of 1932 for the ad's wording, which appeared in the April 1932 issue.[5] However, a similar ad appeared in May 1931 with the lead "To the Soviet Union!" and itinerary therein that matches Ginger's account.[6]) In Moscow, King met American Harry Shapiro, a Harvard Law School graduate, with whom she discussed the ILD and its "Soviet counterpart," the MOPR. "Shapiro urged King to help organize a new association of lawyers" in the States to "fight repression on many fronts" as most MOPR national sections were illegal. He gave her names in Berlin to look up.[4] (Ginger's "trip" narration follows that of the NLG.[7])

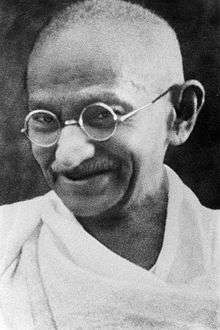

In Berlin, she met with Dr. de:Alfred Apfel, head of a new group called the "International Juridical Assocation" (IJA). The IJA already had sections in Germany, France,[8] and Austria. Sections fell under a "Organizing Committee" "International Juridical Association," headed by Apfel. Their purpose was to defend civil liberties and labor unions.[4] (In 1933, she wrote a letter of protest to the German embassy over the arrest of Apfel by the new Nazi government.[4] The IJA Monthly Bulletin noted his arrest and death, stating that he had been tortured.[9]) (The IJA expanded to Czechoslovakia, Cuba, Netherlands, Indonesia, Mexico, Poland, Venezuela. Members included Mahatma Gandhi.[10][11][12]) A similar brief account of Apfel, Weiss, and formation of the American section of the IJA appears in The Red Angel: The Life and Times of Elaine Black Yoneda.[13]

Upon her return to the states, she rented offices for the American section of the IJA in the St. Denis Building at 80 E 11th Street, New York NY 10003. Ginger states:

Within a few months, she had forty-nine names from twenty states to put on the letterhead, including not only the customary East Coast liberal names but writer Sherwood Anderson from Virginia, and two each from Tennessee and Louisiana, one each from Canada and Puerto Rico.[4]

Funding ran short, so she moved the IJA's offices into her own at 100 Fifth Avenue.[4]

(King's biography in the The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law states only that she came back from Moscow and Berlin to found the International Juridical Association Bulletin.[14]

A 1959 HUAC report stated that George Anderson had helped found the IJA:

George Andersen helped to found a "legal bureau" established in response to this directive in the United States in the early 1930s under the name of the International Juridical Association. He served on the national committee of this Communist-controlled offshoot of the International Labor Defense in 1942. In the same year, he was legal adviser for the Committee for Citizenship Rights, which was intended to protect Communist subversion from any penalties under the law.[3]

The report also carefully notes that Anderson was an NOL member, too.[3]

Further, both the 1950 and 1959 reports by HUAC document the close association of the IJA and NLG with the "American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born (1934–1952)."[2][3][14]

Merger into NLG

According to HUAC's 1950 report on the NLG, the IJA "quietly disappeared from the American scene in the early 1940's" and merged into the NLG. As proof points, HUAC stated that the December 1942 issue of the International Juridical Association Monthly Bulletin announced the journal's merger into NLG's Lawyers Guild Review. The December 1942 issue also announced that its writers move to the board of editors of the Lawyers Guild Review and take primary responsibility for the material in its "IJA section.".[2] (A Catalogue of the Law Collection at New York University: With Selected Annotations confirms absorption by 1943.[15])

Organization

Founders and officers

According to HUAC,[2] at inception, IJA's officers were:

- Isadore Polier (Shad Polier), executive director

- Carol Weiss King, secretary

- Joseph Kovner, editor of International Juridical Association Bulletin

According to Ginger,[4] at inception IJA's officers were significantly different:

- Carol Weiss King

- Osmond K. Fraenkel, representing the ACLU

- Joseph Brodsky, representing the ILD

- Roy Wilkins, representing the NAACP

- Paul F. Brissenden, Professor at Columbia University

- Jerome Frank, Professor at Yale Law School

- Karl Llewelyn, Professor at Columbia Law University

- Charles Erskine Scott Wood, writer

- Floyd Dell, writer

- Yetta Land, labor lawyer from Cleveland and executive secretary

Members

.jpg)

According to HUAC's 1950 report on the NLG, IJA members included:

- Alger Hiss[2]

- Osmond K. Fraenkel[2]

- Louis F. McCabe[2]

Further, according to the 1950 and 1959 HUAC reports, other IJA members who were both later "leaders" of the NLG and actively associated with the ILD included:

- Joseph Brodsky ("charter member of the Communist Party")[2]

- David J. Bentall[2]

- Osmond K. Fraenkel[2]

- Walter Gellhorn[2]

- Herman A. Gray[2]

- Abraham J. Isserman[2][3]

- Paul J. Kern[2]

- Carol Weiss King (defender of J. Peters, American rezident who created the Ware Group)[2]

- Edward Lamb[2]

- Louis F. McCabe[2]

- Maurice Sugar[2]

- Nathan Witt (member of the Ware Group)[3]

Justine W. Polier was also an member of the IJA's editorial board: Shad Polier met her through IJA meetings.[16][17]

Wobbly Elmer Smith was also a member.[18]

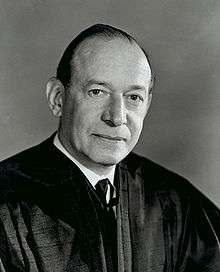

Abe Fortas was a national committee member.[19]

Lee Pressman and Alger Hiss (both members of the Ware Group) were members.[22][23]

Criticism: Communism

HUAC characterized IJA as "Another early front for [communist] lawyers was the International Juridical Association... and its members were closely interlocked with the International Labor Defense as well as the National Lawyers Guild (NLG). Among its prominent members was Alger Hiss." It saw the IJA as active defender of Communists in various kinds of lawsuits; it ascertained a pattern of that "consistently followed the Communist Party line." As early as a report of March 29, 1944, HUAC had considered the IJA a communist "front."[2]

In its 1950 report on the NLG (which includes a brief description of the IJA), HUAC cited the "New York City Council Committee Investigating the

Municipal Civil Service Committee" (1940–1941), which (according to HUAC) stated:

The bulletins of the International Juridical Association from its very inception show that it is devoted to the defense of the Communist Party, Communists, and radical agitators and that it is not limited merely to legal research but to sharp criticism of existing governmental agencies and defense of subversive groups.[2]

HUAC noted that "examination of the [IJA monthly] bulletin reveals consistent support of Communist legal cases during its entire career."[2]

In a footnote in his 1952 memoir, Whittaker Chambers notes:

In the early 1930's, Hiss had been a member of the International Juridical Association, of which the late Carol [Weiss] King, a habitual attorney for Communists in trouble, was a moving spirit. The International Juridical Association has been cited as subversive by the Attorney General. Also among its members: Lee Pressman, Abraham Isserman (one of the attorneys for the eleven convicted Communist leaders), Max Loewenthal, author of a recent book attacking the F.B.I.[24]

Publications

Monthly Bulletin

Throughout, the IJA published a International Juridical Association Monthly Bulletin, edited by Joseph Kovner.[2][25])

HUAC's 1950 report on the NLG noted regarding the IJA that "examination of the bulletin reveals consistent support of Communist legal cases during its entire career.[2]

According to the Encyclopedia of the American Left, the IJA Bulletin was "widely considered the law journal of the Left."[26]

Content included the following:

- 1931: Enjoining Free Speech: Review of a number of labor injunction cases (June 1931)[27]

- 1932: The Hosiery Workers Injunction at Nazareth, PA: Decision of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court; dissenting opinion by Justice Maxey (January 1932)[27]

"The bulletins go free to a mailing list of about 350 persons and organizations."[27]

Archived collections

There appears to be no online source for a digitized (OCR) collection of the bulletin.

The Tamiment Library, whose archives include those of the Communist Party of the USA, has no single collection listed only of the IJA's monthly bulletin, although issues and mention appear in scores of other collections of personal papers, photographs, etc.

According to WorldCat, libraries with full or partial archives include:[28]

- Washington area:

- Library of Congress

- George Washington University Law Library - Jacob Burns Law Library

- University of Virginia - Arthur J. Morris Law Library

- Philadelphia area:

- University of Pennsylvania Law Library - Biddle Law Library

- New York City area:

- New York Public Library System

- New York University - Elmer Holmes Bobst Library (Tamiment Library)

- Yale University - Law School Library

- New York:

- SUNY Binghamton University Libraries (Glenn G. Bartle Library)

- Cornell University Library

- University of Rochester

- SUNY at Buffalo

- New York State Appellate Division, Law Library (Rochester)* North Carolina:

- Duke University, Law Library (J. Michael Goodson Law Library)

- New York State Library (Albany)

- Boston area:

- Harvard College Library

- Harvard Law School Library

- Ohio:

- Cleveland Public Library (Main Library)

- Ohio State University - Michael E. Moritz Law Library

- Indiana:

- Indiana University - Jerome Hall Law Library

- Iowa:

- University of Iowa, Law Library

- Illinois:

- University of Chicago Library

- Northwestern University, School of Law Library - Pritzker Legal Research Center

- Northwestern University (Evanston)

- DePaul University College of Law - Vincent G. Rinn Law Library

- Southern Illinois University, School of Law (Carbondale)

- Michigan:

- University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- University of Michigan Law Library

- Minnesota:

- University of Minnesota, Law Library - Twin Cities Campus

- Kansas:

- University of Kansas Archives - Kenneth Spencer Research Library

- Washburn University Law Library (Topeka)

- Fort Hays State University - Forsyth Library (Hays)

- Louisiana:

- Louisiana State University Law Library - Paul M. Hebert Law Center Library

- Oklahoma:

- University of Oklahoma, Law Center Library

- Texas:

- University of Texas at Austin - Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center (HRC)

- California:

- Los Angeles County Law Library

- University of California, Los Angeles

- University of California Berkeley Law Library - Boalt Law Library

- University of California Berkeley Law Library - McEnerney Law Library

- University of California Berkeley Law Library - BerkeleyLaw Library

- Oregon:

- University of Oregon Libraries - John E. Jaqua Law Library

- Washington:

- University of Washington - Marian Gould Gallagher Law Library

See also

- International Red Aid

- International Labor Defense

- National Lawyers Guild

- Civil Rights Congress

- Carol Weiss King

- Shad Polier

- Alger Hiss

- Abe Fortas

- English-language press of the Communist Party USA

- Mahatma Gandhi

References

- ↑ "Carol Weiss King". Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 The National Lawyers Guild: Legal Bulwark of the Communist Party. U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO). 21 September 1950. pp. 1 (foreign agent), 12–13 (IJA), 17 (members Fraenkel, McCabe). Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Communist Legal Subversion: The Role of the Communist Lawyer. U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO). 16 February 1959. pp. 29 (Anderson), 46 (Isserman), 72 (Witt). Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ginger, Ann Fagan (1993). Carol Weiss King, human rights lawyer, 1895-1952. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. pp. 114 (trip), 115–16 (Shapiro), 117 (Apfel), 119–120 (establishment), 120 (new offices, officers), 150 (Apfel's arrest). ISBN 0-87081-285-8.

- ↑ "Advertisement: May 1st Dneiprostroy: 12 Thrilling Days in the U.S.S.R. with the World Tourists, Inc.". New Masses. April 1932. p. 31. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ "Advertisement: To the Soviet Union!... World Tourists, Inc.". New Masses. May 1931. p. 21. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ "The Guild Practitioner, Volume 41". National Lawyers Guild. 1984: 73. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Adler, Friedrich (1936). The Witchcraft Trial in Moscow. Labour Publications. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ "Monthly Bulletin, Volume 1". The International Juridical Association. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1995). The collected works of Mahatma Gandhi: (21 November, 1929 - 2 April, 1930)., Volume 48. Publ. Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. p. 313. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Gandhi, Mahatma (1970). Collected works, Volume 42. Publ. Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. p. 468. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Gandhi, Mahatma (1930). Young India, Volume 12. Navajivan Publishing House. p. 50. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Raineri, Vivian McGuckin (1991). The Red Angel: The Life and Times of Elaine Black Yoneda. International Publishers. p. 30. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- 1 2 Newman, Roger K. (2009). The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law. Yale University Press. p. 316. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Marke, Julius J. (1953). A Catalogue of the Law Collection at New York University: With Selected Annotations. Lawbook Exchange. p. 1165. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ Ware, Susan (2004). Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century, Volume 5. Cambridge University Press. p. 520. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Foundations of Intelligent Tutoring Systems". Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Copeland, Tom (2011). The Centralia Tragedy of 1919: Elmer Smith and the Wobblies. University of Washington Press. p. 180. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ Hatonn, Gyeorgos C. (1 December 1995). America in Peril -- An Understatement!. Phoenix Source Distributors. p. 17. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "The Supreme Court: Questions & Answers". Time. 13 August 1965. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Abe Fortas". FBI. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ White, G. Edward (2004). Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars: The Covert Life of a Soviet Spy. Oxford University Press. p. 28. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Gall, Gilbert J. (1999). Pursuing Justice: Lee Pressman, the New Deal, and the CIO. SUNY Press. p. 20. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House. LCCN 52005149. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ "Partial List of Publications". University of California, Berkeley. 11 December 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the American Left. Garland. 1990. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Sweet Land of Liberty, 1931–1932 (PDF). American Civil Liberties Union. June 1932. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Monthly bulletin - International Juridical Association.". WorldCat. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

External sources

- The National Lawyers Guild: Legal Bulwark of the Communist Party. U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO). 21 September 1950. pp. 1 (foreign agent), 12–13 (IJA), 17 (members Fraenkel, McCabe). Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Communist Legal Subversion: The Role of the Communist Lawyer. U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO). 16 February 1959. pp. 29 (Anderson), 46 (Isserman), 72 (Witt). Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Ginger, Ann Fagan (1993). Carol Weiss King, human rights lawyer, 1895-1952. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. pp. 114 (trip), 115–16 (Shapiro) 119–120 (establishment), 120 (new offices, officers). ISBN 0-87081-285-8.