International Association of Friends of the Soviet Union

The International Association of Friends of the Soviet Union was an organization formed on the initiative of the Communist International in 1927, with the purpose of coordinating solidarity efforts with the Soviet Union around the world. It grew out of existing initiatives like Friends of Soviet Russia in the United States, the Association of Friends of the New Russia in Germany, and the Hands Off Russia campaign that had emerged during the early 1920s in Great Britain and elsewhere.

Organizational history

Establishment

In 1927 the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics celebrated the 10th Anniversary of the Russian Revolution with much fanfare. Supporters of the Soviet Union flocked to Moscow to attend the official Revolution Day festivities slated for November 7. The Communist International decided to make use of this opportunity to bring together representatives of the various national "friendship societies," centralizing their activities in a single international organization to be known as the International Association of Friends of the Soviet Union.[1] An organizing committee for the new association was named, with representatives of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Communist Party of Great Britain playing a leading role.[1]

The founding congress of FSU was held at the House of the Trade Unions in Moscow November 10–12, 1927. 917 delegates from 40 countries assisted the conference.[2][3][4] Leading figures in the organization were Clara Zetkin and Henri Barbusse. National sections of FSU was formed in various countries.

National sections

Australia

The Australian FSU was established in 1930. In the mid-1930s there was an attempt on behalf of the Commonwealth to ban the organization.[5] The organization was later reconstituted as the Australia-Soviet Friendship League.[6]

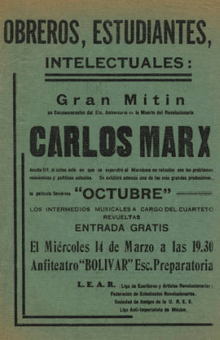

Mexico

In Mexico, the association Amigos de la Union Sovietica combatiente was founded in 1942.[7]

Norway

Sovjet-Unionens venner, the FSU branch in Norway, was founded in 1928.[8] Adam Egede-Nissen was chairman of the organization 1933-1935.[9] Later Nordahl Grieg became the chairman of the organization. The organization was banned under the German occupation, along with the Communist Party, on August 16, 1940.[10]

Romania

An organization following the international model was set up in Romania by the Romanian Communist Party activist Petre Constantinescu-Iaşi in the spring of 1934, at a time of relative détente between the Soviet and Romanian governments (see Greater Romania).[11] Centered in Chişinău and later in Bucharest, it reunited a sizable panel of communist and non-committed intellectuals, and favored Soviet-Romanian cultural ventures, raising controversy after a delegation led by Alexandru Sahia illegally crossed into Soviet territory to attend the anniversary of the October Revolution.[11] It was ultimately outlawed in November of the same year by the Gheorghe Tătărescu cabinet, and was succeeded by the Society for Maintaining Cultural Links between Romania and the Soviet Union, created in May 1935 and itself outlawed in 1938.[11] Various attempts to build on the Amicii URSS legacy during World War II remained unsuccessful, but after the start of Soviet occupation, in November 1944, the Romanian Society for Friendship with the Soviet Union (ARLUS) was founded.[11] It survived as an officially-endorsed cultural institution during the early stages of the Communist regime, but was disbanded in 1964, when the Romanian Communist leader Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej announced a "national path to communism" and proceeded to distance himself from the Soviet Union.[11]

South Africa

The FSU established a branch in South Africa, to which non-communist were invited to join. In March 1934, the FSU took part in the formation of the League against Fascism and War along with the Communist Party, Labour Party members, trade unionists, etc.[12] During the Second World War the FSU campaigned for support for the Soviet war effort. During the early 1940s, the FSU made significant inroads amongst the Indian community.[13]

Spain

Amigos de la Union Sovietica (AUS) was founded in 1925. The organization played an important role in the antifascist struggle during the Spanish Civil War.

Sweden

A Swedish FSU branch, Sovjet-Unionens vänner, was founded in 1930.[14] In 1935 a Social Democrat from Mölndal, Edvin Trettondal, became the chairman of the organization, which resulted in his expulsion from the Social Democratic Party. He later joined the Communist Party. By the late 1930s the organization disintegrated. A section of its members, including Trettondal, formed the association Sovjet-Nytt.[15]

United States of America

In the United States the Friends of Soviet Russia was formally established in August 1921 with Alfred Wagenknecht serving as the group's first Executive Secretary. With the establishment of the new international association the name of the organization was changed to the Friends of the Soviet Union. The organization published a monthly magazine entitled Soviet Russia Today.

Footnotes

- 1 2 Louis Nemzer, "The Soviet Friendship Societies," Public Opinion Quarterly vol. 13, no. 2 (Summer 1949), pg. 266.

- ↑

- ↑ Raymond van Diemel, "I have seen the new Jerusalem"

- ↑ According to another source, the congress was attended by 947 delegates from 43 countries.J. V. Stalin The Fifteenth Congress of the C.P.S.U.(B.), f.12

- ↑ http://www.law.mq.edu.au/html/MqLJ/volume5/vol5_robertson.pdf

- ↑ The Red Army

- ↑ Untitled Document

- ↑ Lund-rapporten

- ↑ Data om det politiske system

- ↑ Friheten - NKUs historie i korte trekk

- 1 2 3 4 5 Adrian Cioroianu, Pe umerii lui Marx. O introducere în istoria comunismului românesc, Editura Curtea Veche, Bucharest, 2005, p. 107–148, 218–219

- ↑ Class & Colour in South Africa - Chapter 20

- ↑ Essop Pahad, The Development of Indian Political Movements in South Africa, 1924-1946, Chapter IV:

- ↑ Övervakningen av "SKP-komplexet"

- ↑ Mölndals stadsbibliotek - Mölndals tredje bibliotek

Further reading

- Louis Nemzer, "The Soviet Friendship Societies," Public Opinion Quarterly vol. 13, no. 2 (Summer 1949), pp. 265–284. In JSTOR

|