Engraved gem

An engraved gem is a small gemstone, usually semi-precious,[1] that has been carved, in the Western tradition normally with images or inscriptions only on one face. The engraving of gemstones was a major luxury art form in the ancient world, and an important one in some later periods.[2]

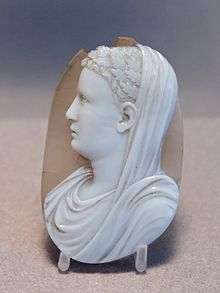

Strictly speaking, engraving means carving in intaglio (with the design cut into the flat background of the stone), but relief carvings (with the design projecting out of the background as in nearly all cameos) are also covered by the term. This article uses "cameo" in its strict sense, to denote a carving exploiting layers of differently coloured stone. The activity is also called gem carving, and the artists gem-cutters. References to antique gems, and intaglios in a jewellery context, will almost always mean carved gems; when referring to monumental sculpture, counter-relief, meaning the same as "intaglio", is more likely to be used. Vessels like the Cup of the Ptolemies and heads or figures carved in the round are also known as "hardstone carvings" and similar terms.

Glyptics, or "glyptic art", covers the field of small carved stones, including cylinder seals and inscriptions, especially in an archaeological context. Though they were keenly collected in antiquity, most carved gems originally functioned as seals, often mounted in a ring; intaglio designs register most clearly when viewed by the recipient of a letter as an impression in hardened wax. A finely carved seal was practical, as it made forgery more difficult – the distinctive personal signature did not really exist in antiquity.

Technique

Gems were mostly cut by using abrasive powder from harder stones in conjunction with a hand-drill, probably often set in a lathe. Emery has been mined for abrasive powder on Naxos since antiquity. Some early types of seal were cut by hand, rather than a drill, which does not allow fine detail. There is no evidence that magnifying lenses were used by gem cutters in antiquity. A medieval guide to gem-carving techniques survives from Theophilus Presbyter. Byzantine cutters used a flat-edged wheel on a drill for intaglio work, while Carolingian ones used round-tipped drills; it is unclear where they learnt this technique from. In intaglio gems at least, the recessed cut surface is usually very well preserved, and microscopic examination is revealing of the technique used.[3] The colour of several gemstones can be enhanced by a number of artificial methods, using heat, sugar and dyes. Many of these can be shown to have been used since antiquity – since the 7th millennium BC in the case of heating.[4]

History

The technique has an ancient tradition in the Near East, and is represented in all or most early cultures from the area, and the Indus Valley civilization. The cylinder seal, whose design only appears when rolled over damp clay, from which the flat ring type developed, was the usual form in Mesopotamia, Assyria and other cultures, and spread to the Minoan world, including parts of Greece and Cyprus. These were made in various types of stone, not all hardstone. The Greek tradition emerged in Ancient Greek art under Minoan influence on mainland Helladic culture, and reached an apogee of subtlety and refinement in the Hellenistic period. Pre-Hellenic Ancient Egyptian seals tend to have inscriptions in hieroglyphs rather than images. The Biblical Book of Exodus describes the form of the hoshen, a ceremonial breastplate worn by the High Priest, bearing twelve gems engraved with the names of the Twelve tribes of Israel.

Round or oval Greek gems (along with similar objects in bone and ivory) are found from the 8th and 7th centuries BC, usually with animals in energetic geometric poses, often with a border marked by dots or a rim.[5] Early examples are mostly in softer stones. Gems of the 6th century are more often oval,[6] with a scarab back (in the past this type was called a "scarabaeus"), and human or divine figures as well as animals; the scarab form was apparently adopted from Phoenicia.[7] The forms are sophisticated for the period, despite the usually small size of the gems.[8] In the 5th century gems became somewhat larger, but still only 2-3 centimetres tall. Despite this, very fine detail is shown, including the eyelashes on one male head, perhaps a portrait. Four gems signed by Dexamenos of Chios are the finest of the period, two showing herons.[9]

Relief carving became common in 5th century BC Greece, and gradually most of the spectacular carved gems in the Western tradition were in relief, although the Sassanian and other traditions remained faithful to the intaglio form. Generally a relief image is more impressive than an intaglio one; in the earlier form the recipient of a document saw this in the impressed sealing wax, while in the later reliefs it was the owner of the seal who kept it for himself, probably marking the emergence of gems meant to be collected or worn as jewellery pendants in necklaces and the like, rather than used as seals – later ones are sometimes rather large to use to seal letters. However inscriptions are usually still in reverse ("mirror-writing") so they only read correctly on impressions (or by viewing from behind with transparent stones). This aspect also partly explains the collecting of impressions in plaster or wax from gems, which may be easier to appreciate than the original.

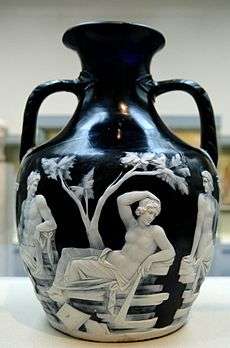

The cameo, which is rare in intaglio form, seems to have reached Greece around the 3rd century; the Farnese Tazza is the only major surviving Hellenistic example (depending on the date assigned to the Gonzaga Cameo – see below), but other glass-paste imitations with portraits suggest that gem-type cameos were made in this period.[10] The conquests of Alexander the Great had opened up new trade routes to the Greek world and increased the range of gemstones available.[11] Roman gems generally continued Hellenistic styles, and can be hard to date, until their quality sharply declines at the end of the 2nd century AD. Philosophers are sometimes shown; Cicero refers to people having portraits of their favourite on their cups and rings.[12] The Romans invented cameo glass, best known from the Portland Vase, as a cheaper material for cameos, and one that allowed consistent and predictable layers on even round objects.

During the European Middle Ages antique engraved gems were one classical art form which was always highly valued, and a large but unknown number of ancient gems have (unlike most surviving classical works of art) never been buried and then excavated. Gems were used to decorate elaborate pieces of goldsmith work such as votive crowns, book-covers and crosses, sometimes very inappropriately given their subject matter. Matthew Paris illustrated a number of gems owned by St Albans Abbey, including one large Late Roman imperial cameo (now lost) called Kaadmau which was used to induce overdue childbirths – it was slowly lowered, with a prayer to St Alban, on its chain down the woman's cleavage, as it was believed that the infant would flee downwards to escape it,[13] a belief in accordance with the views of the "father of mineralogy", Georgius Agricola (1494–1555) on jasper.[14] Some gems were engraved, mostly with religious scenes in intaglio, during the period both in Byzantium and Europe.[15]

In the West production revived from the Carolingian period, when rock crystal was the commonest material. The Lothair Crystal (or Suzanna Crystal, British Museum, 11.5 cm diameter), clearly not designed for use as a seal, is the best known of 20 surviving Carolingian large intaglio gems with complex figural scenes, although most were used for seals.[16] Several crystals were designed, like the Susanna Crystal, to be viewed through the gem from the unengraved side, so their inscriptions were reversed like the seals. In wills and inventories, engraved gems were often given pride of place at the head of a list of treasures.[17]

Some gems in a remarkably effective evocation of classical style were made in Southern Italy for the court of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor in the first half of the 13th century, several in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris. Meanwhile, the church led the development of large, often double-sided, metal seal matrices for wax seals that were left permanently attached to charters and similar legal documents, dangling by a cord, though smaller ring seals that were broken when a letter was opened remained in use. It is not clear to what extent this also continued practices in the ancient world.

Renaissance revival

The late medieval French and Burgundian courts collected and commissioned gems, and began to use them for portraits. The British Museum has what is probably a seated portrait of John, Duke of Berry in intaglio on a sapphire, and the Hermitage has a cameo head of Charles VII of France.[18]

Interest had also revived in Early Renaissance Italy, where Venice soon became a particular centre of production. Along with the Roman statues and sarcophagi being newly excavated, antique gems were prime sources for artists eager to regain a classical figurative vocabulary. Cast bronze copies of gems were made, which circulated around Italy, and later Europe.[19] Among very many examples of borrowings that can be traced confidently, the Felix or Diomedes gem owned by Lorenzo il Magnifico (see below), with an unusual pose, was copied by Leonardo da Vinci and may well have provided the "starting point" for one of Michelangelo's ignudi on the Sistine Chapel ceiling.[20] Another of Lorenzo's gems supplied, probably via a drawing by Perugino, a pose used by Raphael.[21]

By the 16th century carved and engraved gems were keenly collected across Europe for dedicated sections of a cabinet of curiosities, and their production revived, in classical styles; 16th-century gem-cutters working with the same types of sardonyx and other hardstones and using virtually the same techniques, produced classicizing works of glyptic art, often intended as forgeries, in such quantity that they compromised the market for them, as Gisela Richter observed in 1922.[22] Even today, Sir John Boardman admits that "We are sometimes at a loss to know whether what we are looking at belongs to the 1st or the 15th century AD, a sad confession for any art-historian."[23] Other Renaissance gems reveal their date by showing mythological scenes derived from literature that were not part of the visual reportoire in classical times, or borrowing compositions from Renaissance paintings, and using "compositions with rather more figures than any ancient engraver would have tolerated or attempted".[23] Among artists, the wealthy Rubens was a notable collector.[24]

Parallel traditions

Engraved gems occur in the Bible, especially when the hoshen and ephod worn by the High Priest are described; though these were inscribed with the names of the tribes of Israel in letters, rather than any images. A few identifiably Jewish gems survive from the classical world, including Persia, mostly with the owner's name in Hebrew, but some with symbols such as the menorah.[25] Many gems are inscribed in the Islamic world, typically with verses from the Koran, and sometimes gems in the Western tradition just contain inscriptions.

Many Asian and Middle Eastern cultures have their own traditions, although for example the important Chinese tradition of carved gemstones and hardstones, especially jade carving, is broader than the European one of concentration on a flattish faced stone that might fit into a ring. Seal engraving covers the inscription that is printed by stamping, which nearly always only contains script rather than images. Other decoration of the seal itself was not intended to be reproduced.

Iconography

The iconography of gems is similar to that of coins, though more varied. Early gems mostly show animals. Gods, satyrs, and mythological scenes were common, and famous statues often represented – much modern knowledge of the poses of lost Greek cult statues such as Athena Promachos comes from the study of gems, which often have clearer images than coins.[26] A 6th(?) century BC Greek gem already shows Ajax committing suicide, with his name inscribed.[27] The story of Heracles was, as in other arts, the most common source of narrative subjects. A scene may be intended as the subject of an early Archaic gem, and certainly appears on 6th century examples from the later Archaic period.[28]

Portraits of monarchs are found from the Hellenistic period onwards, although as they do not usually have identifying inscriptions, many fine ones cannot be identified with a subject. In the Roman Imperial period, portraits of the imperial family were often produced for the court circle, and many of these have survived, especially a number of spectacular cameos from the time of Augustus. As private objects, produced no doubt by artists trained in the tradition of Hellenistic monarchies, their iconography is less inhibited than the public state art of the period about showing divine attributes as well as sexual matters.[29] The identity and interpretation of figures in the Gemma Augustea remains unclear. A number of gems from the same period contain scenes apparently from the lost epic on the Sack of Troy, of which the finest is by Dioskurides (Chatsworth House).[30]

Renaissance and later gems remain dominated by the Hellenistic reportoire of subjects, though portraits in contemporary styles were also produced.

Collectors

Famous collectors begin with King Mithridates VI of Pontus (d. 63 BC), whose collection was part of the booty of Pompey the Great, who donated it to the Temple of Jupiter in Rome.[31] Julius Caesar was determined to excel Pompey in this as in other areas, and later gave six collections to his own Temple of Venus Genetrix; according to Suetonius gems were among his varied collecting passions.[32] Many later emperors also collected gems. Chapters 4-6 of Book 37 of the Natural History of Pliny the Elder give a summary art history of the Greek and Roman tradition, and of Roman collecting. According to Pliny Marcus Aemilius Scaurus (praetor 56 BC) was the first Roman collector.[33]

As in later periods objects carved in the round from semi-precious stone were regarded as a similar category of object; these are also known as hardstone carvings. One of the largest, the Coupe des Ptolémées was probably donated to the Basilica of Saint-Denis, near Paris, by Charles the Bald, as the inscription on its former gem-studded gold Carolingian mounting stated; it may have belonged to Charlemagne. One of the best collections of such vessels, though mostly plain without carved decoration, was looted from Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade, and is in the Treasury of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice. Many of these retain the medieval mounts which adapted them for liturgical use.[34] Like the Coupe des Ptolémées, most objects in European museums lost these when they became objects of classicist interest from the Renaissance onwards, or when the mounts were removed for the value of the materials, as happened to many in the French Revolution.

The collection of 827 engraved gems of Pope Paul II,[35] which included the "Felix gem" of Diomedes with the Palladium,[36] was acquired by Lorenzo il Magnifico; the Medici collection included many other gems and was legendary, valued in inventories much higher than his Botticellis. Somewhat like Chinese collectors, Lorenzo had all his gems inscribed with his name.[37]

The Gonzaga Cameo passed through a series of famous collections before coming to rest in the Hermitage. First known in the collection of Isabella d'Este, it passed to the Gonzaga Dukes of Mantua, Emperor Rudolf II, Queen Christina of Sweden, Cardinal Decio Azzolini, Livio Odescalchi, Duke of Bracciano, and Pope Pius VI before Napoleon carried it off to Paris, where his Empress Joséphine gave it to Alexander I of Russia after Napoleon's downfall, as a token of goodwill.[38] It remains disputed whether the cameo is Alexandrian work of the 3rd century BC, or a Julio-Claudian imitation of the style from the 1st century AD.[39]

Three of the largest cameo gems from antiquity were created for members of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and seem to have survived above ground since antiquity. The large Gemma Augustea appeared in 1246 in the treasury of the Basilique St-Sernin, Toulouse. In 1533, King François I appropriated it and moved it to Paris, where it soon disappeared around 1590. Not long thereafter it was fenced for 12,000 gold pieces to Emperor Rudolph II; it remains in Vienna, alongside the Gemma Claudia. The largest flat engraved gem known from antiquity is the Great Cameo of France, which entered (or re-entered) the French royal collection in 1791 from the treasury of Sainte-Chapelle, where it had been since at least 1291.

In England, a false dawn of gem collecting was represented by Henry, Prince of Wales' purchase of the cabinet of the Flemish antiquary Abraham Gorlaeus in 1609,[40] and engraved gems featured among the antiquities assembled by Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel. Later in the century William Cavendish, 2nd Duke of Devonshire, formed a collection of gems that is still conserved at Chatsworth.[41] In the eighteenth century a more discerning cabinet of gems was assembled by Henry Howard, 4th Earl of Carlisle, acting upon the advice of Francesco Maria Zanetti and Francesco Ficoroni; 170 of the Carlisle gems, both Classical and post-Classical, were purchased in 1890 for the British Museum.

By the mid-eighteenth century prices had reached such a level that major collections could only be formed by the very wealthy; lesser collectors had to make do with collecting plaster casts,[42] which was also very popular, or buying one of many sumptuously illustrated catalogues of collections that were published.[43] Catherine the Great's collection is in the Hermitage Museum; one large collection she had bought was the gems from the Orléans Collection.[44] Louis XV of France hired Dominique Vivant to assemble a collection for Madame de Pompadour.

In the eighteenth century British aristocrats were able to outcompete even the agents for royal and princely collectors on the Continent, aided by connoisseur-dealers like Count Antonio Maria Zanetti and Philipp von Stosch. Zanetti travelled Europe in pursuit of gems hidden in private collections for the British aristocrats he tutored in connoisseurship;[45] his own collection was described in A.F. Gori, Le gemme antiche di Anton Maria Zanetti (Venice, 1750), illustrated with eighty plates of engravings from his own drawings. Baron Philipp von Stosch (1691–1757), a Prussian who lived in Rome and then Florence, was a major collector, as well as a dealer in engraved gems: "busy, unscrupulous, and in his spare time a spy for England in Italy".[46] Among his contemporaries, Stosch made his lasting impression with Gemmæ Antiquæ Cælatæ (Pierres antiques graveés) (1724), in which Bernard Picart's engravings reproduced seventy antique carved hardstones like onyx, jasper and carnelian from European collections. He also encouraged Johann Lorenz Natter (1705–1763) whom Stosch set to copying ancient carved gems in Florence. Frederick the Great of Prussia bought Stosch's collection in 1765 and built the Antique Temple in the park of the Sanssouci Palace to house his collections of ancient sculpture, coins and over 4,000 gems – the two were naturally often grouped together. The gems are now in the Antikensammlung Berlin.

The collection of "Consul" Joseph Smith (1682–1770), British consul in Venice was bought by George III of England and remains in the Royal Collection. The collections of Charles Towneley, Richard Payne Knight and Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode were bought by or bequeathed to the British Museum, founding their very important collection.[47] But the most famous English collection was that formed by the 4th Duke of Marlborough (1739–1817), "which the Duke kept in his bedroom and resorted to as a relief from his ambitious wife, his busy sister and his many children".[48] This included collections formerly owned by the Gonzagas of Mantua (later owned by Lord Arundel), the 2nd Earl of Bessborough, and the brother of Lord Chesterfield, who himself warned his son in one of his Letters against "days lost in poring upon imperceptible intaglios and cameos".[49] The collection, including its single most famous cameo, the "Marlborough gem" depicting an initiation of Cupid and Psyche, was dispersed after a sale in 1899, fortunately timed for the new American museums and provided the core of the collection of the Metropolitan in New York and elsewhere,[19] with the largest group still together being about 100 in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.[49]

Prince Stanisław Poniatowski (1754–1833) "commissioned about 2500 gems and encouraged the belief that they were, in fact, ancient." He presented a set of 419 plaster impressions of his collection to the King of Prussia which now form the Daktyliothek Poniatowski in Berlin, where they were recognised as modern in 1832, mainly because the signatures of ancient artists from very different times were found on gems in too consistent a style.[50]

Artists

As in other fields, not many ancient artists' names are known from literary sources, although some gems are signed. According to Pliny, Pyrgoteles was the only artist allowed to carve gems for the seal rings of Alexander the Great. Most of the most famous Roman artists were Greeks, like Dioskurides, who is thought to have produced the Gemma Augustea, and is recorded as the artist of the matching signet rings of Augustus – very carefully controlled, they allowed orders to be issued in his name by his most trusted associates. Other works survive signed by him (rather more than are all likely to be genuine), and his son Hyllos was also a gem engraver.[51]

The Anichini family were leading artists in Venice and elsewhere in the 15th and 16th centuries. Many Renaissance artists no doubt kept their activities quiet, as they were passing their products off as antique. Other specialist carvers included Giovanni Bernardi (1494–1553), Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio (c. 1500–1565), Giuseppe Antonio Torricelli (1662–1719), the German-Italian Anton Pichler (1697–1779) and his sons Giovanni and Luigi, Charles Christian Reisen (Anglo-Norwegian, 1680–1725). Other sculptors also carved gems, or had someone in their workshop who did. Leone Leoni said he personally spent two months on a double-sided cameo gem with portraits of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and his wife and son.[52]

The Scot James Tassie (1735–1799), and his nephew William (1777–1860) developed methods for taking hard impressions from old gems, and also for casting new designs from carved wax in enamel, enabling a huge production of what are really imitation engraved gems. The fullest catalogue of his impressions ("Tassie gems") was published in 1791, with 15,800 items.[53] There are complete sets of the impressions in the Hermitage, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and in Edinburgh.[54] Other types of imitation became fashionable for ladies' brooches, such as ceramic cameos by Josiah Wedgwood in jasperware. The engraved gem fell permanently out of fashion from about the 1860s,[19] perhaps partly as a growing realization of the number of gems that were not what they seemed to be scared collectors. Among the last practitioners was James Robertson, who sensibly moved into the new art of photography.

Imitations

Cameo glass was invented by the Romans in about 30BC to imitate engraved hardstone cameos, with the advantage that consistent layering could be achieved even on round vessels – impossible with natural gemstones. It was however very difficult to manufacture and surviving pieces, mostly famously the Portland Vase, are actually much rarer than Roman gemstone cameos.[55] The technique was revived in the 18th and especially 19th centuries in England and elsewhere,[56] and was most effectively used in French Art Nouveau glass that made no attempt to follow classical styles.

The Middle Ages, which lived by charters and other sealed documents, were at least as keen on using seals as the ancient world, now creating them for towns and church institutions, but they normally used metal matrices and signet rings. However some objects, like a 13th-century Venetian Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, mimicked the engraved gem.[57]

Another offshoot of the mania for engraved gems is the fine-grained slightly translucent stoneware called jasperware that was developed by Josiah Wedgwood and perfected in 1775.[58] Though white-on-blue matte jasperware is the most familiar Wedgwood ceramic line, still in production today and widely imitated since the mid-19th century, white-on-black was also produced. Wedgwood made notable jasperware copies of the Portland Vase and the Marlborough gem, a famous head of Antinous,[59] and interpreted in jasperware casts from antique gems by James Tassie. John Flaxman's neoclassical designs for jasperware were carried out in the extremely low relief typical of cameo production. Some other porcelain imitated three-layer cameos purely by paint, even in implausible objects like a flat Sèvres tea-tray of 1840.[60]

Scholars

Gems were a favourite topic for antiquaries from the Renaissance onwards, culminating in the work of Philipp von Stosch, described above. Major progress in understanding Greek gems was made in the work of Adolf Furtwängler (1853–1907, father of the conductor, Wilhelm). Among recent scholars Sir John Boardman (b. 1927) has made a special contribution, again concentrating on Greek gems.

Notes

- ↑ Fully half of the antique engraved gems in the Berlin museums and the British Museum are either sard or carnelian, Etta M. Saunders, noted (Saunders, "Goddess Riding a Goat-Bull Monster: A Ceres Zodiac Gem from the Walters Art Gallery" The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 49/50 (1991/1992;7-11) note 19. .

- ↑ The three preeminent European collections of post-Classical engraved gems are the Cabinet des Médailles at the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris, the Habsburg collection, Vienna, and the British Museum, London, O. M. Dalton observed in "Mediæval and Later Engraved Gems in the British Museum — I" The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 23 No. 123 (June 1913:128-136) and "II" The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 24 No. 127 (October 1913:28-32).

- ↑ Kornbluth, 8-16 quotes passages from Theophilius and others, and discusses various techniques. See Theophilius's article for full on-line texts.

- ↑ Thoresen, "Gemstone enhancement"

- ↑ Boardman, 39 See Beazley for more detail.

- ↑ "Lenticular" or "lentoid" gems have the form of a lens.

- ↑ Beazley, Later Archaic Greek gems: introduction.

- ↑ Boardman, 68-69

- ↑ Boardman, 129-130

- ↑ Boardman, 187-188

- ↑ Beazley, "Hellenistic gems: introduction"

- ↑ Boardman, 275-6

- ↑ Henderson, 112-113

- ↑ De Natura fossilium Bk 1

- ↑ Examples: 14th century French Crucifixion, Rosary pendant, 15th century, both onyx and in the MMA New York.

- ↑ Kornbluth, 1, 4. Susanna Crystal, British Museum.

- ↑ Kornbluth, 1, 4-6

- ↑ Campbell, 411

- 1 2 3 Draper, James David. "Cameo Appearances". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (August 2008)

- ↑ Claire Clark, Kenneth in J. Farago (ed)Leonardo's projects, c. 1500-1519. Volume 3 of Leonardo da Vinci, selected scholarship, Publisher Taylor & Francis, 1999, ISBN 0-8153-2935-0, ISBN 978-0-8153-2935-0. p. 28/160 Google books. Image and description by Boardman

- ↑ Henk Th. van Veen. The translation of Raphael's Roman style. Volume 22 of Groningen studies in cultural change, GSCC ; 22, p. 26, Peeters Publishers, 2007. ISBN 90-429-1855-1, ISBN 978-90-429-1855-9. Google books

- ↑ "Nowadays, however, they have been somewhat neglected—probably because a genuine gem is difficult to distinguish from forged one, and collectors have grown timid in consequence" (Richter, "Engraved Gems" The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 17.9 (September 1922:193-196) p. 193

- 1 2 Beazley, Boardman lecture

- ↑ Getty, Collectors

- ↑ Beazley Archive, "Late Antique, Early Christian and Jewish gems: Sasanian gems – Christian and Jewish"

- ↑ Numismatic evidence is the other most indicative evidence of the general pose of locally important cult images.

- ↑ Beazley, Geometric and Early Archaic gems: Island gems 6th down.

- ↑ Beazley, Archaic period pages

- ↑ Hennig, 154-5. British Museum on the Blacas Cameo of Augustus.

- ↑ Hennig, 153, Boardman, 275-6

- ↑ Pliny, see below. Whether he was right to claim Mithridates as the first collector is dubious.

- ↑ De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius, (The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius), Fordham online text

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History, xxxvii.5

- ↑ Treasury of San Marco

- ↑ Getty Collectors, under Pietro Barbó

- ↑ It passed into the Arundel collection and came to Oxford: see Ashmolean image and description and Graham Pollard, "The Felix Gem at Oxford and its provenance" The Burlington Magazine 119 No. 893 (August 1977:574).

- ↑ Online: The Introduction from Lorenzo de'Medici, Collector of Antiquities', by Laurie Fusco & Gino Corti, Cambridge UP 2006, which gives a survey of early Renaissance collecting in general. On his signing his gems see Draper

- ↑ Gonzaga Cameo Exhibition in Mantua further details

- ↑ Mantua exhibition

- ↑ Roy Strong, Henry Prince of Wales and England's Lost Renaissance (1986:199).

- ↑ Diana Scarisbrick, "The Devonshire Parure", Archaeologia 108 (1986:241).

- ↑ "Sulphurs" provided even finer detail; James Tassie made a career of casting gems in plaster and in coloured opaque glass.

- ↑ Apart from those mentioned below, there is information on other notable collections from the Getty Museum

- ↑ Hermitage Museum

- ↑ His correspondence with Henry Howard, 4th Earl of Carlisle is published by Diana Scarisbrick, "Gem Connoisseurship – The 4th Earl of Carlisle's Correspondence with Francesco de Ficoroni and Antonion Maria Zanetti", The Burlington Magazine 129No. 1007 (February 1987:90-104).

- ↑ Beazley, Boardman Lecture

- ↑ Towneley's were bought from his heirs, the others bequeathed. See King, 218-225 for a selection of highlights

- ↑ Beazley, Marlborough Collection

- 1 2 Beazley, The Marlborough Gems, Boardman Lecture.

- ↑ Beazley, The Poniatowski Collection of gems. More details in The Bernie Madoff of Gem Collectors

- ↑ Boardman, 275-6. Hennig 153-4

- ↑ Metropolitan

- ↑ An earlier version is on Google books A Catalogue, Of Impressions In Sulphur: Of Antique And Modern Gems From Which Pastes Are Made And Sold (1775) (ISBN 110459093X / 1-104-59093-X)

- ↑ Beazley, Tassie

- ↑ Trentinella, Rosemarie. "Roman Cameo Glass". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–9. link (October 2003, retr. 16 September, 2009); Whitehouse, David. Roman glass in the Corning Museum of Glass, Volume 1 Corning Museum of Glass. Google books

- ↑ Texas A&M University Museum Exhibition feature George Woodall and the Art of English Cameo Glass

- ↑ picture and link

- ↑ Robin Reilly, Wedgwood Jasper London, 1972.

- ↑ Antinoos.info See "Gems" section for gem and casts etc

- ↑ Sèvres tea-tray from the Metropolitan museum of Art

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glyptics. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Intaglios. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cameos. |

- "Beazley" The Classical Art Research Centre, Oxford University. Beazley Archive – Extensive website on classical gems; page titles used as references

- Boardman, John ed., The Oxford History of Classical Art, 1993, OUP, ISBN 0-19-814386-9

- Campbell, Gordon (ed). The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, Oxford University Press US, 2006, ISBN 0-19-518948-5, ISBN 978-0-19-518948-3 Google books

- Furtwängler, Adolf. Die antiken Gemmen, 1900. This photo repertory was the cornerstone of modern studies.

- Henderson, George. Early Medieval Art, 1972, rev. 1977, Penguin.

- Henig, Martin (ed), A Handbook of Roman Art, Phaidon, 1983, ISBN 0-7148-2214-0

- King, C. W.; Handbook of Engraved Gems, 1866, reprinted Kessinger Publishing, 2003, ISBN 0-7661-5164-6, ISBN 978-0-7661-5164-2 Google books

- Kornbluth, Genevra Alisoun. Engraved gems of the Carolingian empire, Penn State Press, 1995, ISBN 0-271-01426-1. Google books

- Thoresen, Lisbet. "On Gemstones: Gemological and Analytical Studies of Ancient Intaglios and Cameos." In Ancient Glyptic Art- Gem Engraving and Gem Carving. LThoresen.com (February 2009)

- Gems and gem engraving by Pliny the Younger

Further reading

- Boardman, John. Island Gems, 1963.

- Boardman, John. Archaic Greek Gems, 1968.

- Brown, Clifford M. (ed). Engraved Gems : Survivals and Revivals, National Gallery of Art Washington, 1997. ISBN 0-89468-271-7, ISBN 978-0-89468-271-1

- Barrett, Caitlín E. "Plaster Perspectives on "Magical Gems": Rethinking the Meaning of "Magic" in Cornell's Dactyliotheca". Cornell Collection of Antiquities. Cornell University Library. Retrieved 26 May 2015. Archived May 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

External links

- Beazley Archive – Extensive site on classical gems

- Carvers and Collectors, a 2009 exhibition at the Getty Villa, with many features

- Digital Library Numis (DLN) Online books and articles on engraved gems

- The Johnston collection of engraved gems at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Damen, Giada. "Antique Engraved Gems and Renaissance Collectors", In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. online (March 2013)

- Gems Collection: Cornell Collection of Antiquities, at Cornell University Library and Cornell: Gem Impressions Collection.