Lateral ventricles

| Lateral ventricles | |

|---|---|

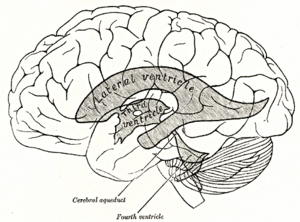

Scheme showing relations of the ventricles to the surface of the brain; oriented facing left. | |

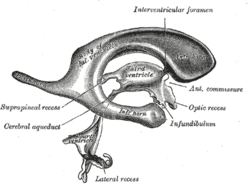

Drawing of a cast of the ventricular cavities, viewed from the side; oriented facing right. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ventriculus lateralis |

| MeSH | A08.186.211.276.650 |

| NeuroNames | hier-191 |

| NeuroLex ID | Lateral ventricle |

| TA | A14.1.09.272 |

| FMA | 78448 |

The lateral ventricles are part of the ventricular system of the brain. Each cerebral hemisphere contains a lateral ventricle. The lateral ventricles are the largest of the ventricles.

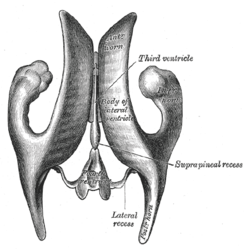

Each lateral ventricle resembles a C-shaped structure that begins at an inferior horn in the temporal lobe, travels through a body in the parietal lobe and frontal lobe, and ultimately terminates at the interventricular foramina where each lateral ventricle connects to the central third ventricle. Along the path, a posterior horn extends backward into the occipital lobe, and an anterior horn extends farther into the frontal lobe.

Structure

Each lateral ventricle has three horns also called cornus. They can be referred to by their position in the ventricle, or by the lobe that they extend into.

The anterior horn of lateral ventricle or frontal horn, passes forward and to the side, with a slight inclination downward, from the interventricular foramen into the frontal lobe, and curves around the front of the caudate nucleus. Its floor is formed by the upper surface of the reflected portion of the corpus callosum, the rostrum. It is bounded medially by the front part of the septum pellucidum, and laterally by the head of the caudate nucleus. Its apex reaches the posterior surface of the genu of the corpus callosum.

The posterior horn of lateral ventricle or occipital horn, passes into the occipital lobe. Its direction is backward and lateralward, and then medial ward. Its roof is formed by the fibers of the corpus callosum passing to the temporal and occipital lobes. On its medial wall is a longitudinal eminence, the calcar avis (hippocampus minor), which is an involution of the ventricular wall produced by the calcarine sulcus. Above this the forceps posterior of the corpus callosum, sweeping around to enter the occipital lobe, causes another projection, termed the bulb of the posterior cornu. The calcar avis and bulb of the posterior cornu are extremely variable in their degree of development; in some cases they are ill-defined, in others prominent.

The inferior horn of lateral ventricle or temporal horn, is the largest of the horns. It traverses the temporal lobe, forming a curve around the posterior end of the thalamus. It passes at first backward, lateralward, and downward, and then curves forward to within 2.5 cm. of the apex of the temporal lobe, its direction is fairly well indicated on the brain surface by the superior temporal sulcus. Its roof is formed chiefly by the inferior surface of the tapetum of the corpus callosum, but the tail of the caudate nucleus and the stria terminalis also extend forward in the roof of the temporal horn to its extremity; the tail of the caudate nucleus joins the putamen. Its floor presents the following parts: the hippocampus, the fimbria hippocampi, the collateral eminence, and the choroid plexus. When the choroid plexus is removed, a cleft-like opening is left along the medial wall of the temporal horn; this cleft constitutes the lower part of the choroidal fissure.

The body of the lateral ventricle is the central portion, just posterior to the frontal horn. The trigone of the lateral ventricle is a triangular area defined by the temporal horn inferiorly, the occipital horn posteriorly, and the body of the lateral ventricle anteriorly. The cella media is the central part of the lateral ventricle. Ependyma cover the inside of the lateral ventricles and are epithelial cells.[1]

Development

The lateral ventricles, similarly to other parts of the ventricular system of the brain, develop from the central canal of the neural tube. Specifically, the lateral ventricles originate from the portion of the tube that is present in the developing prosencephalon, and subsequently in the developing telencephalon.[2] During the first three months of prenatal development the central canal expands into lateral, third and fourth ventricles, connected by thinner channels.[3] In the lateral ventricles, specialized areas – choroid plexuses – appear, which produce cerebrospinal fluid. If its production is bigger than reabsorption or its circulation is blocked – the enlargement of the ventricles may appear and cause a hydrocephalus. Fetal lateral ventricles may be diagnosed using linear or planar measurements.[4]

Clinical significance

The volume of the lateral ventricles are known to increase with age. They are also enlarged in a number of neurological conditions and are on average larger in patients with schizophrenia,[5] bipolar disorder,[6] major depressive disorder[7] and Alzheimer's disease.[8]

The structures of the ventricular system are embryologically derived from the neural canal, the centre of the neural tube.

As the part of the primitive neural tube that will develop into the brainstem, the neural canal expands dorsally and laterally, creating the fourth ventricle, whereas the neural canal that does not expand and remains the same at the level of the midbrain superior to the fourth ventricle forms the cerebral aqueduct. The fourth ventricle narrows at the obex (in the caudal medulla), to become the central canal of the spinal cord.

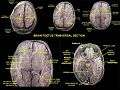

Additional images

Position of lateral ventricles (shown in red).

Position of lateral ventricles (shown in red). Drawing of a cast of the ventricular cavities, viewed from above.

Drawing of a cast of the ventricular cavities, viewed from above. Lateral ventricles

Lateral ventricles- Lateral ventricle

- Temporal horn of lateral ventricle

- Lateral ventricles

Brain dissected after Pr. Nicolas method - second piece

Brain dissected after Pr. Nicolas method - second piece

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lateral ventricles. |

References

- ↑ Crossman, A R (2005). Neuroanatomy. Elsevier. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-443-10036-9.

- ↑ Le, Tao; Bhushan, Vikas; Vasan, Neil (2010). First Aid for the USMLE Step 1: 2010 20th Anniversary Edition. USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-07-163340-6.

- ↑ Carlson, Bruce M. (1999). Human Embryology & Developmental Biology. Mosby. pp. 237–238. ISBN 0-8151-1458-3.

- ↑ Glonek, M; Kedzia, A; Derkowski, W (2003). "Planar measurements of foetal lateral ventricles". Folia morphologica. 62 (3): 263–5. PMID 14507062.

- ↑ Wright IC, Rabe-Hesketh S, Woodruff PW, David AS, Murray RM, Bullmore ET (January 2000). "Meta-analysis of regional brain volumes in schizophrenia". Am J Psychiatry. 157 (1): 16–25. doi:10.1176/ajp.157.1.16. PMID 10618008.

- ↑ Kempton, M.J., Geddes, J.R, Ettinger, U. et al. (2008). "Meta-analysis, Database, and Meta-regression of 98 Structural Imaging Studies in Bipolar Disorder," Archives of General Psychiatry, 65:1017–1032 see also MRI database at www.bipolardatabase.org.

- ↑ Kempton MJ, Salvador Z, Munafò MR, Geddes JR, Simmons A, Frangou S, Williams SC (2011). "Structural Neuroimaging Studies in Major Depressive Disorder: Meta-analysis and Comparison With Bipolar Disorder". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 68 (7): 675–90. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.60. PMID 21727252. see also MRI database at www.depressiondatabase.org

- ↑ Nestor, S; Rupsingh, R; Borrie, M; Smith, M; Accomazzi, V; Wells, J; Fogarty, J; Bartha, R. "Ventricular Enlargement as a Surrogate Marker of Alzheimer Disease Progression Validated Using ADNI". Brain. 131 (9): 2443–2454. doi:10.1093/brain/awn146.