Annexation of Goa

| Operation Vijay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| a Governor-General. | |||||||

Operation Vijay (Hindi: विजय Vijay, lit. "Victory"), the code name of the armed action, was an action by the Indian Armed Forces that ended the rule of Portugal in its exclaves in India in 1961. The operation involved air, sea and land strikes for over 36 hours, and was a decisive victory for India, ending 451 years of Portuguese overseas provincial governance in Goa. The war lasted two days and twenty-two Indians and thirty Portuguese were killed in the fighting.[1] The brief conflict drew a mixture of worldwide praise and condemnation. In India, the action was seen as a liberation of historically Indian territory, while Portugal viewed it as an aggression against national soil and its citizens.

Background

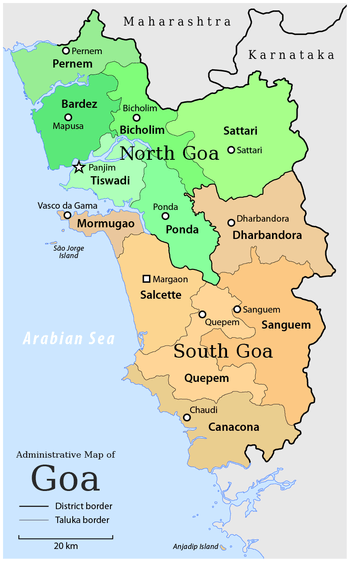

After India's independence from the British Empire in August 1947, Portugal continued to hold a handful of exclaves on the Indian subcontinent—the districts of Goa, Daman and Diu and Dadra and Nagar Haveli—collectively known as the Estado da Índia. Goa, Daman and Diu covered an area of around 1,540 square miles (4,000 km2) and held a population of 637,591.[4] The Goan diaspora was estimated at 175,000 (about 100,000 within the Indian Union, mainly in Bombay).[5] Religious distribution was 61% Hindu, 36.7% Christian (mostly Catholic), 2.2% Muslim.[5] Economy was primarily based on agriculture, although the 1940s and 1950s saw a boom in mining—principally iron ore and some manganese.[5]

Local resistance to Portuguese rule

Resistance to Portuguese rule in Goa in the 20th century was pioneered by Tristão de Bragança Cunha, a French-educated Goan engineer who founded the Goa Congress Committee in Portuguese India in 1928. Cunha released a booklet called 'Four hundred years of Foreign Rule', and a pamphlet, 'Denationalisation of Goa', intended to sensitise Goans to the oppression of Portuguese rule. Messages of solidarity were received by the Goa Congress Committee from leading figures in the Indian independence movement like Dr. Rajendra Prasad, Jawaharlal Nehru, Subhas Chandra Bose, and several others. On 12 October 1938, Cunha with other members of the Goa Congress Committee met Subhas Chandra Bose, the President of the Indian National Congress, and on his advice, opened a Branch Office of the Goa Congress Committee at 21, Dalal Street, Bombay. The Goa Congress was also made affiliate to the Indian National Congress and Cunha was selected its first President.[6]

In June 1946, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia, an Indian Socialist leader, entered Goa on a visit to his friend, Dr. Julião Menezes, a nationalist leader, who had founded in Bombay the Gomantak Praja Mandal and edited the weekly newspaper, Gomantak. Cunha and other leaders were also with him.[6] Ram Manohar Lohia advocated the use of non-violent Gandhian techniques to oppose the government.[7] On 18 June 1946, the Portuguese government disrupted a protest in Panaji (then spelled as Panjim) against the suspension of civil liberties organised by Lohia, Cunha along with others like Purushottam Kakodkar and Laxmikant Bhembre in defiance of a ban on public gatherings and arrested them.[8][9] There were intermittent mass demonstrations from June to November.

In addition to non-violent protests, armed groups such as the Azad Gomantak Dal (The Free Goa Party) and the United Front of Goans conducted violent attacks aimed at weakening Portuguese rule in Goa.[10] The Indian government supported the establishment of armed groups like the Azad Gomantak Dal, giving them full financial, logistic and armament support. The armed groups acted from bases situated in Indian territory and under cover of Indian police forces. The Indian government—through these armed groups—attempted to destroy economic targets, telegraph and telephone lines, road, water and rail transport, in order to impede economic activity and create conditions for a general uprising of the population.[11]

Commenting on the armed resistance, Portuguese army officer, Capt. Carlos Azaredo (now retired General) stationed with the army in Goa, stated in the Portuguese newspaper Expresso: "To the contrary to what is being said, the most evolved guerilla warfare which our Armed Forces encountered was in Goa. I know what I'm talking about, because I also fought in Angola and in Guiné. In 1961 alone, until December, around 80 policemen died. The major part of the terrorists of Azad Gomantak Dal were not Goans. Many had fought in the British Army, under General Montgomery, against the Germans."[12]

Diplomatic efforts to resolve Goa dispute

On 27 February 1950, the Government of India asked the Portuguese government to open negotiations about the future of Portuguese colonies in India.[13] Portugal asserted that its territory on the Indian subcontinent was not a colony but part of metropolitan Portugal and hence its transfer was non-negotiable; and that India had no rights to this territory because the Republic of India did not exist at the time when Goa came under Portuguese rule.[14] When the Portuguese Government refused to respond to subsequent aide-mémoires in this regard, the Indian government, on 11 June 1953, withdrew its diplomatic mission from Lisbon.[15]

By 1954, the Republic of India instituted visa restrictions on travel from Goa to India which paralysed transport between Goa and other exclaves like Daman, Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli.[13] Meanwhile, the Indian Union of Dockers had, in 1954, instituted a boycott on shipping to Portuguese India.[16] Between 22 July and 2 August 1954, armed activists attacked and forced the surrender of Portuguese forces stationed in Dadra and Nagar Haveli.[17]

On 15 August 1955, 3000–5000 unarmed Indian activists[18] attempted to enter Goa at six locations and were violently repulsed by Portuguese police officers, resulting in the deaths of between 21[19] and 30[20] people.[21] The news of the massacre built public opinion in India against the presence of the Portuguese in Goa.[22] On 1 September 1955, India shut its consul office in Goa.[23]

In 1956, Portuguese ambassador to France, Marcello Mathias, along with Portuguese Prime Minister António de Oliveira Salazar, argued in favour of a referendum in Goa to determine its future. This proposal was however rejected by the Ministers for Defence and Foreign Affairs. The demand for a referendum was again made by presidential candidate General Humberto Delgado in 1957.[13]

Prime Minister Salazar, alarmed by India's hinted threats at armed action against its presence in Goa, first asked the United Kingdom to mediate, then protested through Brazil and eventually asked the United Nations Security Council to intervene.[24] Mexico offered the Indian government its influence in Latin America to bring pressure on the Portuguese to relieve tensions.[25] Meanwhile, Krishna Menon, India's defence minister and head of India's UN delegation, stated in no uncertain terms that India had not "abjured the use of force" in Goa,[24] The US ambassador to India, John Kenneth Galbraith, requested the Indian government on several occasions to resolve the issue peacefully through mediation and consensus rather than armed conflict.[26][27]

Eventually, on 10 December, nine days prior to the invasion, Nehru stated to the press that "Continuance of Goa under Portuguese rule is an impossibility".[24] The American response was to warn India that if and when India's armed action in Goa was brought to the UN security council, it could expect no support from the US delegation.[28]

On 24 November 1961, the Sabarmati, a passenger boat passing between the Portuguese-held island of Anjidiv and the Indian port of Kochi, was fired upon by Portuguese ground troops, resulting in the death of a passenger, as well as injuries to the chief engineer of the boat. The action was precipitated by Portuguese fears that the boat carried a military landing party intent on storming the island.[29] The incidents lent themselves to foster widespread public support in India for military action in Goa.

The Annexation of Dadra and Nagar Haveli

The hostilities between India and Portugal started seven years before the invasion of Goa, when Dadra and Nagar Haveli were invaded and occupied by pro-Indian forces with the support of the Indian authorities.

Dadra and Nagar Haveli were two Portuguese landlocked exclaves of the Daman district, totally surrounded by Indian territory. The connection between the exclaves and the coastal territory of Daman had to be made by crossing about 20 km of Indian territory. Dadra and Nagar Haveli did not have any Portuguese military garrison, but only police forces.

The Indian Government started to develop isolation actions against Dadra and Nagar Haveli already in 1952, including the creation of impediments to the transit of persons and goods between the two landlocked enclaves and Daman.

In July 1954, pro-Indian forces, including members of organisations like the United Front of Goans (UFG), the National Movement Liberation Organisation (NMLO), the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Azad Gomantak Dal, with the support of Indian Police forces, started to launch assaults against Dadra and Nagar Haveli. On the night of 22 July, UFG forces stormed the small Dadra police station, killing police sergeant Aniceto do Rosário and constable António Fernandes who resisted the attack. On 28 July, RSS forces took Naroli police station.

Meanwhile, the Portuguese authorities asked the Indian Government for permission to cross their territory with reinforcements to Dadra and Nagar Haveli, which was denied.

Surrounded and prevented from receiving reinforcements by the Indian Authorities, the Portuguese Administrator and police forces in Nagar Haveli eventually surrendered to the Indian police forces on 11 August 1954.

Portugal appealed to the International Court of Justice, which, in the decision of 12 April 1960 "Case Concerning Right of Passage Over Indian Territory", stated that Portugal had sovereign rights over the territories of Dadra and Nagar Haveli but India had the right to deny passage to armed personnel of Portugal over Indian territories. Therefore, the Portuguese authorities could not legally pass through Indian territory.

On 31 December 1974, a treaty was signed between India and Portugal with the Portuguese recognising full sovereignty of India over Goa, Daman, Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli.[30]

Events preceding the hostilities

Indian military build-up

On receiving the go-ahead for military action and the mandate of the capture of all occupied territories for the Indian government, Lieutenant-General Chaudhari of India's Southern Army fielded the 17th Infantry Division and the 50th Parachute Brigade (50th Para Brigade) commanded by Major-General K.P. Candeth. The assault on the enclave of Daman was assigned to the Maratha Light Infantry, 1st Battalion (1st Maratha LI) while the operations in Diu were assigned to the Rajput Regiment, 20th Battalion (20th Rajput) and The Madras Regiment, 4th Battalion (4th Madras).[31]

Meanwhile, the Commander-in-Chief of India's Western Air Command, Air Vice Marshal Erlic Pinto, was appointed as the commander of all air resources assigned to the operations in Goa. Air resources for the assault on Goa were concentrated in the bases at Pune and Sambra (Belgaum).[31] The mandate handed to Air Vice Marshal Erlic Pinto by the Indian Air Command was listed out as follows:

- The destruction of Goa's lone airfield in Dabolim, without causing damage to the terminal building and other airport facilities.

- Destruction of the wireless station at Bambolim, Goa.

- Denial of airfields at Daman and Diu, which were, however, not to be attacked without prior permission.

- Support to advancing ground troops.

The Indian Navy deployed two warships—the INS Rajput, an 'R' Class destroyer, and the INS Kirpan, a Blackwood class anti-submarine frigate—off the coast of Goa. The actual attack on Goa was delegated to four task groups: a Surface Action Group comprising five ships: Mysore, Trishul, Betwa, Beas and Cauvery; a Carrier Group of five ships: Delhi, Kuthar, Kirpan, Khukri and Rajput centred around the light aircraft carrier Vikrant; a Mine Sweeping Group consisting of mine sweepers including Karwar, Kakinada, Cannonore and Bimilipatan and a Support Group which consisted of the Dharini.[32]

The Portuguese Mandate

In March 1960, Portuguese Defence Minister General Botelho Moniz, told Prime Minister Salazar that a sustained Portuguese campaign against decolonisation would create for the army "a suicide mission in which we could not succeed". His opinion was shared by Army Minister Colonel Almeida Fernandes, by the Army under secretary of State Lieutenant-Colonel Costa Gomes and by other top officers.[33]

Ignoring this advice, Salazar sent the following message to Governor General Vassalo e Silva in Goa on 14 December, in which he ordered the Portuguese forces in Goa to fight to the last man.[34]

Radio 816 / Lisbon 14-Dec.1961: You understand the bitterness with which I send you this message. It is horrible to think that this may mean total sacrifice, but I believe that sacrifice is the only way for us to keep up to the highest traditions and provide service to the future of the Nation. Do not expect the possibility of truce or of Portuguese prisoners, as there will be no surrender rendered because I feel that our soldiers and sailors can be either victorious or dead. These words could, by their seriousness, be directed only to a soldier of higher duties fully prepared to fulfill them. God will not allow you to be the last Governor of the State of India.

Salazar then asked Vassalo e Silva to hold out for at least eight days, within which time he hoped to gather international support against the Indian invasion.[34]

Portuguese military preparations

Following the Annexation of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, the Portuguese authorities made a marked strengthening of the garrison of Portuguese India, with units and personnel sent from European Portugal and from the Portuguese African provinces of Angola and Mozambique.

Portuguese military preparations began in earnest in 1954, following the Indian economic blockade, the beginning of the anti-Portuguese attacks in Goa and the invasion of Dadra and Nagar Haveli. Three light infantry battalions (one each sent from European Portugal, Angola and Mozambique) and support units were transported to Goa, reinforcing a local raised battalion and increasing the Portuguese military presence there from almost nothing to 12,000 men.[12] Other sources refer that, in the end of 1955, Portuguese forces in India represented a total of around 8,000 men (Europeans, Africans and Indians), including 7,000 in the land forces, 250 in the naval forces, 600 in the Police and 250 in the Fiscal Guard, split by the districts of Goa, Daman and Diu.[35]

The Portuguese forces were organised as the Armed Forces of the State of India (FAEI, Forças Armadas do Estado da Índia), under a unified command headed by General Paulo Bénard Guedes, which accumulated the civil role of Governor-General with the military role of Commander-in-Chief. General Bénard Guedes would end his commission in 1958, with General Vassalo e Silva being appointed to replace him in both the civil and military roles.[35]

The Portuguese Government and military commands were, however, well aware that even with this effort to strengthen the garrison of Goa, the Portuguese forces would never be sufficient to face a conventional attack from the Indian Armed Forces, which could easily concentrate against that territory land forces overwhelmingly stronger than the Portuguese ones, as well as air and naval forces. The Portuguese Government hoped however to politically deter the Indian government from attempting a military aggression, with the showing of a Portuguese strong will to fight and to sacrifice to defend Goa.[35]

In 1960, during an inspection visit to Portuguese India and referring to a predictable start of guerrilla activities in Angola, the Under Secretary of State of the Army Costa Gomes stated the necessity to reinforce the Portuguese military presence in that African territory, partly at the expense of the military presence in Goa, where the then existing 7,500 men were too many just to deal with anti-Portuguese actions, and too few to face an Indian invasion, which, if it were to occur, would have to be handled by other means. This led to the Portuguese forces in India suffering a sharp reduction to about 3,300 soldiers.[35]

Faced with this reduced force strength, the strategy employed to defend Goa against an Indian invasion was based in the Plano Sentinela (Sentinel Plan) which divided the territory into four defence sectors (North, Center, South and Mormugão) and the Plano de Barragens (Barrage Plan) which envisaged the demolishing of all bridges and links to delay the invading army, as well as the mining of approach roads and beaches. Defence units were organised as four battlegroups (agrupamentos), with a battlegroup assigned to each sector and tasked with slowing the progression of an invading force. Commenting on the Plano Sentinela, Capt. Carlos Azaredo who was stationed in Goa at the time of hostilities states in Portuguese newspaper Expresso on 8 December 2001, "It was a totally unrealistic and unachievable plan, which was quite incomplete. It was based on exchange of ground with time. But, for this purpose, portable communication equipment was necessary."[12] Plans to mine roads and beaches were also unviable because of a desperate shortage of mines.[36]

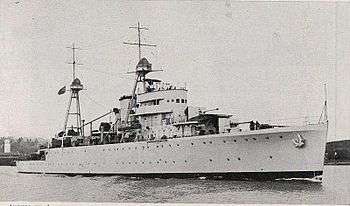

Navy

The naval component of the FAEI, were the Naval Forces of the State of India (FNEI, Forças Navais do Estado da Índia), headed by the Naval Commander of Goa, Commodore Raúl Viegas Ventura. The only significant Portuguese Navy warship present in Goa, at the time of invasion, was the sloop NRP Afonso de Albuquerque.[37] The vessel was armed with four 120 mm guns capable of two shots per minute, and four automatic rapid firing guns. In addition to the sloop, the Portuguese Naval Forces had three light patrol boats (lanchas de fiscalização), each armed with a 20mm Oerlikon gun, one based in each Goa, Daman and Diu. There were also five merchant marine ships in Goa.[38] An attempt by Portugal to send naval warships to Goa to reinforce its marine defences was foiled when President Nasser of Egypt denied the ships access to the Suez Canal.[39][40][41]

Ground Forces

Portuguese ground defences were organised as the Land Forces of the State of India (FTEI, Forças Terrestres do Estado da Índia), under the Portuguese Army's Independent Territorial Command of India, headed by Brigadier António José Martins Leitão. At the time of the invasion, they consisted of a total of 3,995 men, including 810 native (Indo-Portugueses – Indo-Portuguese) soldiers, many of whom had little military training and were utilised primarily for security and anti-extremist operations. These forces were divided amongst the three Portuguese enclaves in India.[35] The Portuguese Army units in Goa included four motorised reconnaissance squadrons, eight rifle companies (caçadores), two artillery batteries and an engineer detachment. In addition to the military forces, the Portuguese defences counted with the civil internal security forces of the Portuguese India. These included the State of India Police (PEI, Polícia do Estado da Índia), general police corps modelled after the Portuguese Public Security Police; the Fiscal Guard (Guarda Fiscal), responsible of the Customs enforcement and border protection; and the Rural Guard (Guarda Rural), game wardens. In 1958, as an emergency measure, the Portuguese Government gave a provisional military status to PEI and the Fiscal Guard, placing them under the command of the FAEI. The security forces were also divided amongst the three districts and were mostly made up of Indo-Portuguese policemen and guards. Different sources indicate between 900 and 1400 men as the total effective for these forces, at the time of the invasion.[35]

Air Defence

The Portuguese Air Force did not have any presence in Portuguese India, with the exception of a single officer with the role of air adviser in the office of the Commander-in-Chief.[35]

On 16 December, the Portuguese Air Force was placed on alert to transport ten tons of anti-tank grenades in two DC-6 aircraft from Montijo Air Base in Portugal to Goa assist in its defence. When the Portuguese Air Force was unable to obtain stopover facilities at any air base along the way – most nations including Pakistan denying passage of Portuguese military aircraft – the mission was passed on to the civilian airline TAP which offered a Lockheed Constellation (registration CS-TLA) on charter for the job. However, when permission to transport weapons through Karachi was denied by the Pakistani Government, the Lockheed Constellation landed in Goa at 1800 hours on 17 December with a consignment of half a dozen bags of sausages as food supplies instead of the intended grenades. However the aircraft also arrived with a contingent of female paratroopers to assist in the evacuation of Portuguese civilians.[42]

The Portuguese air presence in Goa at the time of hostilities was thus limited to the presence of two civilian transport aircraft, one belonging to the Portuguese international airline (TAP) and the other to the Goan airline Portuguese India Airlines (TAIP): a Lockheed Constellation and a Douglas DC-4 Skymaster aircraft. The Indians claimed that the Portuguese had a squadron of F-86 Sabres stationed at Dabolim Airport—which later turned out to be false intelligence. Air defence was limited to a few obsolete anti-aircraft guns manned by two artillery units who had been smuggled into Goa disguised as soccer teams.[29]

Portuguese civilian evacuation

The military buildup created panic amongst Europeans in Goa, who were desperate to evacuate their families before the commencement of hostilities. On 9 December, the vessel India arrived at Goa's Mormugão port en route to Lisbon from Timor. Despite orders from the Portuguese government in Lisbon not to allow anyone to embark on this vessel, the Governor General of Goa, Manuel Vassalo e Silva, allowed 700 Portuguese civilians of European origin to board the ship and flee Goa. The ship had capacity for only 380 passengers, and was filled to its limits, with evacuees occupying even the ship's toilets.[29] On arranging this evacuation of women and children, Vassalo e Silva remarked to the press, "If necessary, we will die here." Evacuation of European civilians continued by air even after the commencement of Indian air strikes.[43]

Indian reconnaissance operations

Indian reconnaissance operations had commenced on 1 December, when two Indian Leopard class frigates, the INS Betwa and the INS Beas, undertook linear patrolling of the Goa coast at a distance of 8 miles (13 km). By 8 December, the Indian Air Force had commenced baiting missions and fly-bys to lure out Portuguese air defences and fighters.

On 17 December, a tactical reconnaissance flight conducted by Sqn Ldr I S Loughran in a Vampire NF.54 Night Fighter over Dabolim Airport in Goa was met with 5 rounds fired from a ground anti aircraft gun. The aircraft took evasive action by drastically dropping altitude and escaping out to sea. The anti aircraft gun was later recovered near the ATC building with a round jammed in its breech.[44]

The Indian light aircraft carrier INS Vikrant was deployed 75 miles (121 km) off the coast of Goa to head a possible amphibious operation on Goa, as well as to deter any foreign military intervention.

Commencement of hostilities

The military actions in Goa

The ground attack on Goa: North and North East sectors

On 11 December 1961, 17th Infantry Division and attached troops of the Indian Army were ordered to advance into Goa to capture Panaji and Mormugão. The main thrust on Panaji was to be made by the 50th Para Brigade Group—one of the Indian Army's most elite airborne units—led by Brigadier Sagat Singh from the north. Another thrust was to be carried by 63rd Indian Infantry Brigade from the east. A deceptive thrust, in company strength, was to be made from the south along the Majali-Canacona-Margao axis.[45]

Although the Indian 50th Para Brigade was charged with merely assisting the main thrust conducted by the 17th Infantry, its units moved rapidly across minefields, roadblocks and four riverine obstacles to be the first to reach Panaji.[46]

Hostilities at Goa began at 9:45 on 17 December 1961, when a unit of Indian troops attacked and occupied the town of Maulinguém in north east Goa, killing two Portuguese soldiers in the process. The Portuguese 2nd EREC (esquadrão de reconhecimento—reconnaissance squadron), stationed near Maulinguém, asked for permission to engage the Indians, but permission was refused at about 13:45.[47] During the afternoon of the 17th, the Portuguese command issued instructions that all orders to defending troops would be issued directly by headquarters, bypassing the local command outposts. This led to confusion in the chain of command.[47] At 02:00 on 18 December, the 2nd EREC was sent to the town of Doromagogo to support the withdrawal of police forces present in the area, and were attacked by Indian Army units on their return journey.[47]

At 04:00, the Indian assault commenced with artillery bombardment on Portuguese positions south of the town of Maulinguém, which was launched on the basis of the false intelligence that the Portuguese had stationed heavy battle tanks in the area. By 04:30, Bicholim was under fire. At 04:40, the Portuguese forces destroyed the bridge at Bicholim and followed this with the destruction of the bridges at Chapora in Colvale and at Assonora at 05:00.[47]

On the morning of 18 December, the 50th Para Brigade of the Indian Army moved into Goa in three columns.

- The eastern column comprised the 2nd Para Maratha advanced towards the town Ponda in central Goa via Usgão.

- The central column consisting of the 1st Para Punjab advanced towards Panaji via the village of Banastari.

- The western column—the main thrust of the attack—comprised the 2nd Sikh Light Infantry as well as an armoured division which crossed the border at 6:30 a.m. in the morning and advanced along Tivim.[45]

At 05:30, Portuguese troops left their barracks at Ponda in central Goa and marched towards the town of Usgão, in the direction of the advancing eastern column of the Indian 2nd Para Maratha and under command of Major Dalip Singh Jind, tanks of Indian 7th Cavalry. At 09:00, these Portuguese troops marching towards Usgão, reported that Indian troops had already reached halfway to the town of Ponda.[47]

By 10:00, Portuguese forces of the 1st EREC, faced with the advancing 2nd Sikh Light Infantry, began a south-bound withdrawal to the town of Mapuca where, by 12:00, they came under the risk of being surrounded by Indian forces. At 12:30, the 1st EREC began a retreat from the town of Mapuca, making way through the Indian forces, with its armoured cars firing ahead to cover the withdrawal of the personnel carrier vehicles. This unit relocated by ferry further south to Panaji.[47]

At 13:30, the bridge at Banastarim was destroyed by the Portuguese, just after the retreat of the 2nd EREC, thus cutting off all road links to the capital city of Panaji.

By 17:45, the forces of the 1st EREC and the 9th Caçadores Company of the Portuguese Battlegroup North had completed its ferry crossing of the Mandovi River to Panaji, just minutes ahead of the arrival of the Indian armoured forces.[47] The Indian tanks had reached Betim, just across the Mandovi River from the capital town of Panaji without encountering any opposition. The 2nd Sikh Light Infantry joined it by 21:00, crossing over mines and demolished bridges en route. In the absence of orders, the unit stayed at Betim for the night.

At 20:00 hours, a Goan by the name of Gregório Magno Antão crossed the Mandovi River from Panaji and delivered a ceasefire offer letter from Major Acácio Tenreiro of the Portuguese Army to Major Shivdev Singh Sidhu, the commanding officer of the Indian 7th Cavalry camped there. The letter stated "The Military Commander of the City of Goa states that he wishes to parley with the commander of the army of the Indian Union with respect to the surrender. Under these conditions, the Portuguese troops must immediately cease fire and the Indian troops do likewise in order to prevent the slaughter of the population and the destruction of the city." [48]

The same night Major Shivdev Singh Sidhu with a force of the 7th Cavalry decided to take Fort Aguada and obtain its surrender, after information received that a number of supporters of the Indian Republic were held prisoners there. However, the Portuguese defenders of the Fort had not yet received orders to surrender and responded by opening fire on Indian forces, Major Sidhu and Captain Vinod Sehgal being killed in the firefight.[45]

The order to cross the Mandovi River was received on the morning of 19 December, upon which two rifle companies of the 2nd Sikh Light Infantry advanced on Panaji at 07:30 and secured the town without facing any resistance. On orders from Brigadier Sagat Singh, the troops entering Panaji removed their steel helmets and donned the Parachute Regiment's maroon berets. Fort Aguada was also captured on that day when the Indian 7th Cavalry attacked the fort with assistance from the armoured division stationed at Betim, and freed its political prisoners.

The advance from the East

Meanwhile, in the east, the 63rd Indian Infantry Brigade advanced in two columns. The right column comprising the 2nd Bihar Battalion and the left column consisting of the 3rd Sikh Battalion linked up at the border town of Mollem and then advanced upon the town of Ponda taking separate routes. By night fall, the 2nd Bihar had reached the town of Candeapur, while the 3rd Sikh had reached Darbondara. Although neither column had encountered any resistance, their further progress was hampered because all bridges spanning the river had been destroyed.

The rear battalion was the 4th Sikh Infantry, which reached Candeapar in the early hours of 19 December, and not to be bogged down by the absence of the Borim bridge (already blown up), went across the Zuari river in their military tankers and then waded across a small creek, in chest high water, to reach a small dock known as Embarcadouro de Tembim in Raia, presently under survey No.44/5 of Raia Village, from where there exists a connecting road to Margão (Old Portuguese Planta 4489 & 4493). At Tembim the 4th Sikh Infantry rear battalion, took some rest in a cattle shed on the small dock, and sprawled on the ground and in the balcony of a house adjacent to the dock, drank some water, retrieved their tankers and then proceeded to Margão—the administrative centre of Southern Goa—by 12:00. From here, the column advanced towards the harbour of Mormugão. En route to this target, the column encountered fierce resistance from a 500-strong Portuguese unit at the village of Verna, where the Indian column was joined by the 2nd Bihar. The Portuguese unit surrendered at 15:30 after fierce fighting, and the 4th Sikh then proceeded to Mormugão and Dabolim Airport, where the main body of the Portuguese Army awaited the Indians.

A decoy attack was staged south of Margão by the 4th Rajput company to mislead the Portuguese. This column overcame minefields, roadblocks and demolished bridges, and eventually went on to help secure the town of Margão.

The air raids over Goa

The first Indian raid was conducted on 18 December on the Dabolim Airport and was in the form of 12 English Electric Canberra aircraft led by Wing Commander N.B. Menon. The raid resulted in the dropping of 63,000 pounds of explosives within minutes, completely destroying the runway. In line with the mandate given by the Air Command, structures and facilities at the airfield were left undamaged.[31]

The second Indian raid was conducted on the same target by eight Canberras led by Wing Commander Surinder Singh, which again left the airport's terminal and other buildings untouched. Two transport aircraft—a Lockheed Constellation belonging to the Portuguese airline TAP and a Douglas DC-4 belonging to the Goan airline TAIP—were parked on the apron. On the night of 18 December, the Portuguese used both aircraft to evacuate the families of some government and military officials in spite of the heavily damaged runway. During the first hours of the evening, airport workers hastily recovered part of the runway. The first aircraft to leave was the TAP Constellation commanded by Manuel Correia Reis, which took off using only 700 metres; the debris from the runway damaged the fuselage with 25 holes and a flat tire. To take off in the short distance, the TAP pilots had jettisoned all the extra seats and other unwanted equipment so that they could do a 'short take-off'.[49] The second to leave was the TAIP DC-4, piloted by TAIP Director Major Solano de Almeida. Both aircraft used the cover of night and very low altitudes to break through Indian aerial patrols and escape to Karachi, Pakistan.[50]

A third Indian raid was carried out by six Hawker Hunters, and was targeted at the wireless station at Bambolim, which was successfully attacked with rockets and gun cannons.

The mandate to support ground troops was served by the de Havilland Vampires of No. 45 squadron which patrolled the sector but did not receive any requests into action. In an incident of friendly fire, two Vampires fired rockets into the positions of the 2nd Sikh Light Infantry injuring two soldiers, while elsewhere, Indian ground troops mistakenly opened fire on an IAF T-6 Texan, causing minimal damage.

In later years, commentators have maintained that India's intense air strikes against the airfields were uncalled-for, since none of the targeted airports had any military capabilities and did not cater to any military aircraft. As such, the airfields were defenceless civilian targets.[50] To this day, the Indian navy continues to control the Dabolim Airport, although this is now used as a civilian airport as well.

The storming of Anjidiv Island

Anjidiv was a small 1.5 km2 island of the Portuguese India, then almost uninhabited, belonging to the District of Goa, although off the coast of the Indian state of Karnataka. On the island stood the ancient Anjidiv Fort, defended by a platoon of Goan soldiers of the Portuguese Army.

The Indian Naval Command assigned the task of securing Anjidiv to the cruiser INS Mysore and the frigate INS Trishul.

Under covering artillery fire from the ships, Indian marines, under the command of Lieutenant Arun Auditto, stormed the island at 14:25 on 18 December and engaged the Portuguese garrison. The assault was repulsed by the Portuguese defenders, with seven Indian marines killed and 19 wounded. Among the Indian casualties were two officers.

The Portuguese defences were eventually overrun after fierce shelling from the Indian ships offshore. The island was secured by the Indians at 14:00 of the next day, almost all the Portuguese defenders being captured, with exception of two corporals and one private. Hidden in the rocks, one corporal surrendered on 19 December. The other corporal was captured in the afternoon of 20 December, but not before launching hand grenades that injured several Indian marines. The last of the three, Goan private Manuel Caetano, became the last Portuguese soldier in India to be captured, only being on 22 December, already after having reached the Indian shore by swimming.

Naval battle at Mormugão harbour

On the morning of 18 December, the Portuguese sloop NRP Afonso de Albuquerque was anchored off Mormugão Harbour. Besides engaging Indian naval units, the Afonso de Albuquerque was also tasked with providing a coastal artillery battery to defend the harbour and adjoining beaches, and providing vital radio communications with Lisbon after on-shore radio facilities had been destroyed in Indian airstrikes.

At 09:00, three Indian frigates led by the INS Betwa took up position off the harbour, awaiting orders to attack the Afonso and secure sea access to the port. At 11:00, Indian planes bombed Mormugão harbour.[2] At 12:00, upon receiving clearance from HQ, the INS Betwa, accompanied by the INS Beas entered the harbour and fired on the Afonso with their 4.5-inch guns while transmitting requests to surrender in morse code between shots. In response, the Afonso lifted anchor, headed out towards the enemy and returned fire with its 120 mm guns.

The Afonso was outnumbered by the Indians, and was at a severe disadvantage since it was in a confined position that restricted its manoeuvring, and because its four 120 mm guns could fire only two rounds a minute, as compared to the 60 rounds per minute of the guns aboard the Indian frigates. A few minutes into the exchange of fire, at 12:15, the Afonso took a direct hit in its control tower, injuring its weapons officer. At 12:25, an anti-personnel shrapnel bomb fired from an Indian vessel exploded directly over the ship, killing its radio officer and severely injuring its commander, Captain António da Cunha Aragão, after which the First Officer Pinto da Cruz took command of the vessel. The ship's propulsion system was also badly damaged in this attack.

At 12:35, the Afonso swerved 180 degrees and was run aground against Bambolim beach. At that time, against the commander's orders, a white flag was hoisted under instructions from the sergeant in charge of signals, but the flag coiled itself around the mast and as a result was not spotted by the Indians, who continued their barrage. The flag was immediately lowered.

Eventually at 12:50, after having fired nearly 400 rounds at the Indians, hitting two of the Indian vessels, and having taken severe damage, the order was given to start abandoning the ship. Under heavy fire, directed at the ship and at the coast, non-essential crew including weapons staff left the ship and went ashore. They were followed at 13:10 by the rest of the crew, who, along with their injured commander, set fire to the ship and disembarked directly onto the beach. Following this, the commander was transferred by car to the hospital at Panaji.

The NRP Afonso de Albuquerque lost 5 dead and 13 wounded in the battle.[2]

The sloop's crew formally surrendered with the remaining Portuguese forces on 19 December 1961 at 2030 hrs.[12]

As a gesture of goodwill, the commanders of the INS Betwa and the INS Beas later visited Captain Aragão as he lay recuperating in bed in Panaji.

The Afonso—having been renamed as Saravastri by the Indian Navy—lay grounded at the beach near Dona Paula, until 1962 when it was towed to Bombay and sold for scrap. Parts of the ship were recovered and are on display at the Naval Museum in Bombay.[2]

The Portuguese patrol boat NRP Sirius, under the command of Lieutenant Marques Silva, was also present at Goa. After observing Afonso running aground and not having communications from the Goa Naval Command, Lieutenant Marques Silva decided to scuttle the Sirius. This was done by damaging the propellers and making the boat hit the rocks. The eight men of the Sirius's crew avoided being captured by the Indian forces, and boarded a Greek freighter on which they reached Pakistan.

The military actions in Daman

The ground attack on Daman

Daman, approximately 72 km2 in area, is at the south end of Gujarat bordering Maharashtra and just about 193 km north of Bombay. The countryside is broken and interspersed with marsh, salt pans, streams, paddy fields, coconut and palm groves. The river Daman Ganga splits the capital city of Daman into halves—Nani Daman (Damão Pequeno) and Moti Daman (Damão Grande). The strategically important features were Daman Fort and the Air Control Tower of Daman Airport.[51]

The Portuguese garrison in Daman was headed by Major António José da Costa Pinto (combining the roles of District Governor and military commander), with 360 Army soldiers, 200 policemen and about 30 customs officials under him. The Portuguese Army forces were made of two companies of caçadores (light infantry) and an artillery battery, organised as the battlegroup "Constantino de Bragança". The artillery battery was armed with 87.6mm guns, but these had insufficient and old ammunition. The Portuguese also placed a 20 mm anti-aircraft gun ten days before the invasion to protect the artillery. Daman had been secured with small minefields and defensive shelters had been built.[38]

The advance on the enclave of Daman was conducted by the 1st Maratha Light Infantry Battalion under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel SJS Bhonsle[51] in a pre-dawn operation on 18 December.[45] The plan was to capture Daman piecemeal in four phases, to start with the area of the airfield, then progressively to area garden, Nani Daman and finally Moti Daman to include the fort.[51]

The advance commenced at 04:00 when one battalion and three companies of Indian soldiers progressed through the central area of the northern territory, aiming to seize the airfield.[38] However, the surprise was lost when the Indian A Company tried to capture the Air Control Tower and the Indian battalion suffered three casualties. The Portuguese lost one soldier dead and six taken captive. The Indian D Company captured a position named "Point 365" just before the next morning. At the crack of dawn, two sorties by Indian Air Force Mystere fighters struck Portuguese mortar positions and guns inside Moti Daman Fort.[51]

At 04:30, the Indian artillery began to bombard Damão Grande. The artillery attack, and transportation difficulties, isolated the Portuguese command post in Damão Grande from the forces in Damão Pequeno. At 07:30, a Portuguese unit at the fortress of São Jerónimo fired mortars on Indian forces attempting to capture the airstrip.[38]

At 11:30, Portuguese forces resisting an Indian advance on the eastern border at Varacunda ran out of ammunition and withdrew westwards to Catra. At 12:00, to delay the Indian advance following the withdrawal from Varacunda, the Portuguese artillery battery on the banks of the Rio Sandalcalo was ordered to open fire. The commander of the battery, Captain Felgueiras de Sousa, instead dismantled the guns and surrendered to the Indians.[38] By 12:00, the airfield was assaulted by the Indian A and C companies simultaneously. In the ensuing exchange of fire the A Company lost one more soldier and seven were wounded.[51]

By 13:00, the remaining Portuguese forces on the east border at Calicachigão-A exhausted their ammunition and retreated towards the coast. By 17:00, in the absence of resistance, the Indians had managed to occupy most of the territory, except the airfield and Damão Pequeno, where the Portuguese were making their last stand. By this time, the Indian Air Force had conducted six air attacks, severely demoralising the Portuguese forces. At 20:00, after a meeting between the Portuguese commanders, a delegation was dispatched to the Indian lines to open negotiations, but was fired on, and was forced to withdraw. A similar attempt by the artillery to surrender at 08:00 of the next day was also fired on.[38]

The Indians assaulted the airfield the next morning, upon which the Portuguese surrendered at 11:00 without a fight.[45] The Portuguese garrison commander Major Costa Pinto,[51] although wounded, was stretchered to the airfield, as the Indians were only willing to accept a surrender from him.[38] Approximately 600 Portuguese soldiers and policemen (including 24 officers[51]) were taken prisoner. The Indians suffered 4 dead and 14 wounded,[51] while the Portuguese suffered 10 dead and two wounded.[45] The 1st Light Maratha Infantry was decorated for the battle with one VSM for the CO, two Sena Medals and five Mentioned in Dispatches.[51]

The Daman air raids

In the Daman sector, Indian Mysteres flew 14 sorties, continuously harassing Portuguese artillery positions.

Naval action at Daman

Like the Vega in Diu, the patrol boat NRP Antares—based at Daman under the command of 2nd Lieutenant Abreu Brito—was ordered to sail out and fight the imminent Indian invasion. The boat stayed in position from 07:00 on 18 December and remained a mute witness to repeated air strikes followed by ground invasion until 19:20, when it lost all communications with land.

With all information pointing to total occupation of all Portuguese enclaves in India, Lt. Brito tried to save his crew and boat by escaping to Karachi in Pakistan. The boat traversed 530 miles (850 km), escaping detection by Indian forces, and arrived at Karachi at 20:00 on 20 December.

The military actions in Diu

The ground attack on Diu

Diu is a 13.8 km by 4.6 km island (area about 40 km2) at the south tip of Gujarat. The island is separated from the mainland by a narrow channel running though a swamp. The channel could only be used by fishing boats and small craft. No bridges crossed the channels at the time of hostilities. The Portuguese garrison in Diu was headed by Major Fernando de Almeida e Vasconcelos (district governor and military commander), with around 400 soldiers and police officers, organised as the battlegroup "António da Silveira".[52]

Diu was attacked on 18 December from the north west along Kob Forte by two companies of the 20th Rajput Battalion—with the capture of the Diu Airfield being the primary objective—and from the northeast along Gogal and Amdepur by the Rajput B Company and the 4th Madras Battalion.[45]

These Indian Army units ignored requests from Wing Commander (rank) M.P.O. "Micky" Blake, planning-in-charge of the Indian Air Force operations in Diu, to attack only on first light when close air support would be available.[52] The Portuguese defences repulsed the attack backed by 87.6mm artillery and mortars,[38] inflicting heavy losses on the Indians.[52] The first attack was made by the 4th Madras on a police border post at 01:30 on 18 December at Gogol and was repulsed by 13 Portuguese police officers.[38] Another attempt by the 4th Madras at 02:00 was again repulsed, this time backed with Portuguese 87.5mm artillery and mortar which suffered due to poor quality of munitions. By 04:00, ten of the original 13 Portuguese defenders at Gogol had been wounded and were evacuated to a hospital. At 05:30, the Portuguese artillery launched a fresh attack on the 4th Madras assaulting Gogol and forced their retreat.[38]

Meanwhile, at 03:00, two companies of the 20th Rajput attempted to cross a muddy swamp[38] separating them from the Portuguese forces at Passo Covo under cover of dark on rafts made of bamboo cots tied to oil barrels.[52] The attempt was to establish a bridgehead and capture the airfield.[45]

This attack was repulsed with fairly heavy losses by a well entrenched unit of Portuguese soldiers armed with small automatic weapons and sten guns[52] as well as light and medium machine guns. According to Indian sources this unit included between 125 and 130 soldiers,[45] but according to Portuguese sources this post was defended by only eight soldiers.[38]

As the Rajputs reached the middle of the creek, the Portuguese on Diu opened fire with two medium and two light machine-guns, capsizing some of the rafts. Major Mal Singh of the Indian Army along with five men pressed on his advance and crossed the creek. On reaching the far bank, he and his men assaulted the light machine gun trenches at Fort-De-Cova and silenced them. The Portuguese medium machine gun fire from another position wounded the officer and two of his men. However, with the efforts of company Havildar Major Mohan Singh and two other men, the three wounded were evacuated back across the creek to safety. As dawn approached, the Portuguese increased the intensity of fire and the battalion's water crossing equipment suffered extensive damage. As a result, the Indian battalion was ordered to fall back to Kob village by first light.[51]

Another assault at 05:00 was similarly repulsed by the Portuguese defenders. At 06:30, Portuguese forces retrieved rafts abandoned by the 20th Rajput, recovered ammunition left behind and rescued a wounded Indian soldier who was given treatment.[38]

At 07:00, with the onset of dawn, Indian air strikes began, forcing the Portuguese to retreat from Passo Covo to the town of Malala. By 09:00 the Portuguese unit at Gogol also retreated[38] allowing the Rajput B Company (who replaced the 4th Madras) to advance under heavy artillery fire and occupy the town.[45] By 10:15, the Indian cruiser INS Delhi, anchored off Diu, began to bombard targets on the shore.[38] At 12:45, Indian jets fired a rocket at a mortar at Diu Fortress causing a fire near a munitions dump, forcing the Portuguese to order the evacuation of the fortress—a task completed by 14:15 under heavy bombardment from the Indians.[38]

At 18:00, the Portuguese commanders agreed in a meeting that, in view of repeated air strikes and the inability to establish contact with headquarters in Goa or Lisbon, there was no way to pursue an effective defence and decided to surrender to the Indians.[38] On 19 December, by 12:00, the Portuguese formally surrendered. The Indians took 403 prisoners, which included the Governor of the island along with 18 officers and 43 sergeants.[51]

In surrendering to the Indians, the Diu Governor stated that he could have kept the Army out for a few weeks but he had no answer to the Air Force. The Indian Air Force was also present at the ceremony and was represented by Gp Capt Godkhindi, Wing Cmdr Micky Blake and Sqn Ldr Nobby Clarke.[52] 7 Portuguese soldiers were killed in the battle.[52]

Major Mal Singh and Sepoy Hakam Singh of the Indian army were awarded Ashok Chakra (Class III).[51]

On 19 December, the 4th Madras C Company landed on the island of Panikot off Diu, where a group of 13 Portuguese soldiers surrendered to them there.[45]

The Diu air raids

The Indian air operations in the Diu Sector were entrusted to the Armaments Training Wing led by Wg Cdr Micky Blake. The first air attacks were made at dawn on 18 December and were aimed at destroying Diu's fortifications facing the mainland. Throughout the rest of the day, the Air Force had at least two aircraft in the air at any time, giving close support to advancing Indian infantry. During the morning, the air force attacked and destroyed Diu Airfield's ATC as well as parts of Diu Fort. On orders from Tactical Air Command located at Pune, a sortie of two Toofanis attacked and destroyed the airfield runway with 4 1000 lb Mk 9 bombs. A second sortie aimed at the runway and piloted by Wg Cdr Blake himself was aborted when Blake detected what he reported as people waving white flags. In subsequent sorties, the Indian Air Force attacked and destroyed the Portuguese ammunition dump as well a patrol boat that attempted to escape from Diu.

In the absence of any Portuguese air presence, Portuguese ground based anti-aircraft units attempted to offer resistance to the Indian raids, but were overwhelmed and quickly silenced, leaving complete air superiority to the Indians. Continued air attacks forced the Portuguese governor of Diu to surrender.

Naval action at Diu

The Indian cruiser INS Delhi was anchored off the coast of Diu and fired a barrage from its 6-inch guns at the Diu Fortress where the Portuguese were holed up. The Commanding Officer of the Indian Air Force operating in the area reported that some of the shells fired from the New Delhi were bouncing off the beach and exploding on the Indian mainland. However, no casualties were reported from this.[53]

At 04:00 on 18 December, the Portuguese patrol boat NRP Vega encountered the New Delhi around 12 miles (19 km) off the coast of Diu, and was attacked with heavy machine gun fire. Staying out of range, the boat had no casualties and minimal damage, the boat withdrew to the port at Diu.

At 07:00, news was received that the Indian invasion had commenced, and the commander of the Vega, 2nd Lt Oliveira e Carmo was ordered to sail out and fight until the last round of ammunition. At 07:30 the crew of the Vega spotted two Indian aircraft on patrol missions and opened fire on them with the ship's 20mm Oerlikon gun. In retaliation the Indian aircraft attacked the Vega twice, killing the captain and the gunner and forcing the rest of the crew to abandon the boat and swim ashore, where they were taken prisoners of war.

UN attempts at ceasefire

On 18 December, a Portuguese request was made to the UN Security Council for a debate on the conflict in Goa. The request was approved when the bare minimum of seven members supported the request (the USA, UK, France, Turkey, Chile, Ecuador, and Nationalist China), two opposed (the Soviet Union and Ceylon), and two abstained (the United Arab Republic and Liberia).[54]

Opening the debate, Portugal's delegate, Dr. Vasco Vieira Garin said that Portugal had consistently shown her peaceful intentions by refraining from any counter-action to India's numerous "provocations" on the Goan border. Dr. Garin also stated that Portuguese forces, though "vastly outnumbered by the invading forces," were putting up "stiff resistance" and "fighting a delaying action and destroying communications in order to halt the advance of the enemy." In response, India's delegate, Mr. Jha said that the "elimination of the last vestiges of colonialism in India" was an "article of faith" for the Indian people, "Security Council or no Security Council." He went on to describe Goa, Daman, and Diu as "an inalienable part of India unlawfully occupied by Portugal."[54]

In the ensuing debate, the US delegate, Adlai Stevenson, strongly criticised India's use of force to resolve her dispute with Portugal, stressing that such resort to violent means was against the charter of the UN. He stated that condoning such acts of armed forces would encourage other nations to resort to similar solutions to their own disputes, and would lead to the death of the United Nations. In response, the Soviet delegate, Valerian Zorin, argued that the Goan question was wholly within India's domestic jurisdiction and could not be considered by the Security Council. He also drew attention to Portugal's disregard for UN resolutions calling for the granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples.[54]

Following the debate, the delegates of Liberia, Ceylon, and the U.A.R. presented a resolution which: (1) stated that "the enclaves claimed by Portugal in India constitute a threat to international peace and security and stand in the way of the unity of the Republic of India; (2) asked the security Council to reject the Portuguese charge of aggression against India; and (3) called upon Portugal "to terminate hostile action and co-operate with India in the liquidation of her colonial possessions in India." This resolution was supported only by the Soviet Union, the other seven members opposing.[54]

After the defeat of the Afro-Asian resolution, a resolution was presented by the United States, Great Britain, France, and Turkey which: (1) Called for the immediate cessation of hostilities; (2) Called upon India to withdraw her forces immediately to "the positions prevailing before 17 Dec 1961." (3) Urged India and Portugal "to work out a permanent solution of their differences by peaceful means in accordance with the principles embodied in the Charter"; and (4) Requested the U.N. Secretary-General "to provide such assistance as may be appropriate."[54]

This resolution received seven votes in favour (the four sponsors and Chile, Ecuador, and Nationalist China) and four against (the Soviet Union, Ceylon, Liberia, and the United Arab Republic). It was thus defeated by the Soviet veto. In a statement after the vote, Mr. Stevenson said that the "fateful" Goa debate might be "the first act of a drama" which could end in the death of the United Nations.[54]

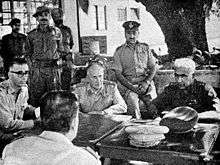

Portuguese surrender

By the evening of 18 December, most of Goa had been overrun by advancing Indian forces, and a large party of more than two thousand Portuguese soldiers had taken position at the military base at Alparqueiros at the entrance to the port town of Vasco da Gama. Per the Portuguese strategy code named Plano Sentinela the defending forces were to make their last stand at the harbour, holding out against the Indians until Portuguese naval reinforcements could arrive. Orders delivered from the Portuguese President called for a scorched earth policy—that Goa was to be destroyed before it was given up to the Indians.[55]

Canadian political scientist Antonio Rangel Bandeira has argued that the sacrifice of Goa was an elaborate public relations stunt calculated to rally support for Portugal's wars in Africa.[33]

Despite his orders from Lisbon, Governor General Manuel António Vassalo e Silva took stock of the numerical superiority of the Indian troops, as well as the food and ammunition supplies available to his forces and took the decision to surrender. He later described his orders to destroy Goa as "um sacrifício inútil" (a useless sacrifice).

In a communication to all Portuguese forces under his command, he stated, "Having considered the defence of the Peninsula of Mormugão… from aerial, naval and ground fire of the enemy and … having considered the difference between the forces and the resources… the situation does not allow myself to proceed with the fight without great sacrifice of the lives of the inhabitants of Vasco da Gama, I have decided with … my patriotism well present, to get in touch with the enemy … I order all my forces to cease-fire."[56]

The official Portuguese surrender was conducted in a formal ceremony held at 2030 hours on 19 December when Governor General Manuel António Vassalo e Silva signed the instrument of surrender bringing to an end 451 years of Portuguese Rule in Goa. In all, 4668 personnel were taken prisoner by the Indians—a figure which included military and civilian personnel, Portuguese, Africans and Goan.[12]

Upon the surrender of the Portuguese governor general, Goa, Daman and Diu was declared a federally administered Union Territory placed directly under the President of India, and Major-General K. P. Candeth was appointed as its military governor. The war had lasted two days, and had cost 22 Indian and 30 Portuguese lives.

Those Indian forces who served within the disputed territories for 48 hours, or flew at least one operational sortie during the conflict, received a General Service Medal 1947 with the Goa 1961 bar.[57]

Portuguese actions post-hostilities

When they received news of the fall of Goa, the Portuguese government formally severed all diplomatic links with India and refused to recognise the incorporation of the seized territories into the Indian Republic. An offer of Portuguese citizenship was instead made to all Goan natives who wished to emigrate to Portugal rather than remain under Indian rule. This was amended in 2006 to include only those who had been born before 19 December 1961. Later, in a show of defiance, Prime Minister Salazar's government offered a reward of US$10,000 for the capture of Brigadier Sagat Singh, the commander of the maroon berets of India's parachute regiment who were the first troops to enter Panaji, Goa's capital.[58]

Lisbon went virtually into mourning, and Christmas celebrations were extremely muted. The US embassy put a curtain in front of its Christmas display in the ground-floor window of the US Information Office. Cinemas and theatres shut down as tens of thousands of Portuguese marched in a silent parade from Lisbon's city hall to the cathedral, escorting the relics of St. Francis Xavier.[59]

Salazar, while addressing the Portuguese National Assembly on 3 January 1962, invoked the principle of national sovereignty, as defined in the legal framework of the Constitution of the Estado Novo. "We can not negotiate, not without denying and betraying our own, the cession of national territory and the transfer of populations that inhabit them to foreign sovereigns," said Salazar.[60] He went on to state that the UN's failure to halt aggression against Portugal, showed that effective power in the U.N. had passed to the Communist and Afro-Asian countries. Dr. Salazar also accused Britain of delaying for a week her reply to Portugal's request to be allowed the use of certain airfields. "Had it not been for this delay," he said, "we should certainly have found alternative routes and we could have rushed to India reinforcements in men and material for a sustained defence of the territory."[54]

Hinting that Portugal would yet be vindicated, Salazar went on to state that "difficulties will arise for both sides when the programme of the Indianization of Goa begins to clash with its inherent culture... It is therefore to be expected that many Goans will wish to escape to Portugal from the inevitable consequences of the invasion."[54]

In the months after the conflict, the Portuguese Government used broadcasts on Emissora Nacional, the Portuguese national radio station, to urge Goans to resist and oppose the Indian administration. An effort was made to create clandestine resistance movements in Goa, and within Goan diaspora communities across the world to use general resistance and armed rebellion to weaken the Indian presence in Goa. The campaign had the full support of the Portuguese government with the ministries of defence, foreign affairs, army, navy and finance involved. A plan was chalked out called the 'Plano Gralha' covering Goa, Daman and Diu, which called for paralysing port operations at Mormugao and Bombay by planting bombs in some of the ships anchored at the ports.[61][62]

On 20 June 1964, Casimiro Monteiro, a Portuguese PIDE agent of Goan descent, along with Ismail Dias, a Goan settled in Portugal, executed a series of bombings in Goa.[63]

Relations between India and Portugal thawed only in 1974, when, following an anti-colonial military coup d'état and the fall of the authoritarian rule in Lisbon, Goa was finally recognised as part of India, and steps were taken to re-establish diplomatic relations with India. In 1992, Portuguese President Mário Soares became the first Portuguese head of state to visit Goa after its annexation by India, following Indian President R. Venkataraman's visit to Portugal in 1990.[64]

Internment and repatriation of POWs

After they surrendered, the Portuguese soldiers were interned by the Indian Army at their own military camps at Navelim, Aguada, Pondá and Alparqueiros under harsh conditions which included sleeping on cement floors and hard manual labour.[29] By January 1962, most POWs had been transferred to the newly established camp at Ponda where conditions were substantially better.[29]

Portuguese non-combatants present in Goa at the surrender—which included Mrs Vasalo D'Silva, wife of the Portuguese Governor General of Goa—were transported by 29 December to Bombay, from where they were repatriated to Portugal. Manuel Vassalo, however, remained along with approximately 3,300 Portuguese combatants as POWs in Goa.

Air Marshal S. Raghavendran, who met some of the captured Portuguese soldiers, wrote in his memoirs several years later "I have never seen such a set of troops looking so miserable in my life. Short, not particularly well built and certainly very unsoldierlike."[65]

In one incident, recounted by Lieutenant Francisco Cabral Couto (now retired general), on 19 March 1962 some of the prisoners tried to escape the Ponda camp in a garbage truck. The attempt was foiled, and the Portuguese officers in charge of the escapees were threatened with court martial and execution by the Indians. This situation was defused by the timely intervention of Ferreira da Silva, a Jesuit military chaplain.[29][66] Following the foiled escape attempt, Captain Carlos Azaredo (now retired general) was beaten with rifle butts by four Indian soldiers while a gun was pointed at him, on the orders of Captain Naik, the 2nd Camp Commander. The beating was in retaliation for Azaredo's telling Captain Naik to "Go to Hell", and was serious enough to make him lose consciousness and cause severe contusions. Captain Naik was later punished by the Indian Army for violating the Geneva Convention.[12]

During the internment of the Portuguese POWs at various camps around Goa, the prisoners were visited by large numbers of Goans—described by Captain Azaredo as "Goan friends, acquaintances, or simply anonymous persons"—who offered the internees cigarettes, biscuits, tea, medicines and money. This surprised the Indian military authorities, who first limited the visits to twice a week, and then only to representatives of the Red Cross.[12]

The captivity lasted for six months "thanks to the stupid stubbornness of Lisbon" (according to Capt. Carlos Azeredo). The Portuguese Government insisted that the POWs be repatriated by Portuguese aircraft—a demand that was rejected by the Indian Government who instead insisted on aircraft from a neutral country. The negotiations were delayed even further when Salazar ordered the detention of 1200 Indians in Mozambique allegedly as a bargaining chip in exchange for Portuguese POWs.[12]

By May 1962, most of the POWs had been repatriated—being first flown to Karachi, Pakistan, in chartered French aircraft, and then sent off to Lisbon by three ships: Vera Cruz, Pátria and Moçambique.[67] On arrival at the Tejo in Portugal, returning Portuguese servicemen were taken into custody by military police at gunpoint without immediate access to their families who had arrived to receive them. Following intense questioning and interrogations, the officers were charged with direct insubordination on having refused to comply with directives not to surrender to the Indians. On 22 March 1963, the governor general, the military commander, his chief of staff, one naval captain, six majors, a sub lieutenant and a sergeant were cashiered by the council of ministers for cowardice and expelled from military service. Four captains, four lieutenants and a lieutenant commander were suspended for six months.[33]

Ex-governor Manuel António Vassalo e Silva had a hostile reception when he returned to Portugal. He was subsequently court martialed for failing to follow orders, expelled from the military and sent into exile. He returned to Portugal only in 1974, after the fall of the regime, and was given back his military status. He was later able to conduct a state visit to Goa, where he was given a warm reception.[68]

International reaction to the capture of Goa

Support

Soviet Union

The head of state of the Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev, who was touring India at the time of the war, made several speeches applauding the Indian action. In a farewell message, he urged Indians to ignore Western indignation as it came "from those who are accustomed to strangle the peoples striving for independence... and from those who enrich themselves from colonialist plunder". Nikita Khrushchev, the de facto Soviet leader, telegraphed Nehru stating that there was "unanimous acclaim" from every Soviet citizen for "Friendly India". The USSR had earlier vetoed a UN security council resolution condemning the Indian invasion of Goa.[69][70][71]

China

In an official statement issued on 19 December, the Chinese government stressed its "resolute support" for the struggle of the people of Asia, Africa and Latin America against "imperialist colonialism". However, the Hong Kong Communist newspaper Ta Kung Pao (regarded as reflecting the views of the Peking Government) described the attack on Goa as "a desperate attempt by Mr. Nehru to regain his sagging prestige among the Afro-Asian nations." The Ta Kung Pao article – published before the statement from the Chinese Government – conceded that Goa was legitimately part of Indian territory and that the Indian people were entitled to take whatever measures were necessary to recover it. At the same time, however, the paper ridiculed Mr. Nehru for choosing "the world's tiniest imperialist country" to achieve his aim and asserted that "internal unrest, the failure of Nehru's anti-China campaign, and the forthcoming election forced him to take action against Goa to please the Indian people."[54]

Arab States

The United Arab Republic expressed its full support for India's "legitimate efforts to regain its occupied territory". A Moroccan Government spokesman said that "India has been extraordinarily patient and a non-violent country has been driven to violence by Portugal"; while Tunisia's Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs of Tunisia, Dr. Sadok Mokaddem expressed the hope that "the liberation of Goa will bring nearer the end of the Portuguese colonial regime in Africa." Similar expressions of support for India were forthcoming from other Arab countries.[54]

Ceylon

Full support for India's action was expressed in Ceylon, where Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike issued an order on 18 December directing that "transport carrying troops and equipment for the Portuguese in Goa shall not be permitted the use of Ceylon's seaports and airports." Ceylon went on, along with delegates from Liberia and the UAR, to present a resolution in the UN in support of India's invasion of Goa.[54]

African states

Before the invasion the press speculated about international reaction to military action and recalled the recent charge by African nations that India was "too soft" on Portugal and was thus "dampening the enthusiasm of freedom fighters in other countries".[24] Many African nations—themselves former European colonies—reacted with delight to the capture of Goa by the Indians. Radio Ghana termed it as the "Liberation of Goa" and went on to state that the people of Ghana would "long for the day when our downtrodden brethren in Angola and other Portuguese territories in Africa are liberated." Adelino Gwambe, the leader of the Mozambique National Democratic Union stated: "We fully support the use of force against Portuguese butchers."[24]

Condemnation

- "The casualties were minimum. I am in favour of all wars being like the war between India and Portugal—peaceful and quickly over!"—J. K. Galbraith, former US ambassador to India[56]

United States

The United States' official reaction to the invasion of Goa was delivered by Adlai Stevenson in the United Nations Security Council, where he condemned the armed action of the Indian government and demanded that all Indian forces be unconditionally withdrawn from Goan soil.

To express its displeasure with the Indian action in Goa, the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee attempted, over the objections of President John F. Kennedy, to cut the 1962 foreign aid appropriation to India by 25 percent.[72]

Referring to the perception, especially in the West, that India had previously been lecturing the world about the virtues of nonviolence, President Kennedy told the Indian ambassador to the US, "You spend the last fifteen years preaching morality to us, and then you go ahead and act the way any normal country would behave… People are saying, the preacher has been caught coming out of the brothel."[73]

In an article titled "India, The Aggressor", The New York Times on 19 December 1961, stated "With his invasion of Goa Prime Minister Nehru has done irreparable damage to India's good name and to the principles of international morality."[74]

Life International, in its issue dated 12 February 1962, carried an article titled "Symbolic pose by Goa's Governor" in which it expressed its vehement condemnation of the military action.

The world's initial outrage at pacifist India's resort to military violence for conquest has subsided into resigned disdain. And in Goa, a new Governor strikes a symbolic pose before portraits of men who had administered the prosperous Portuguese enclave for 451 years. He is K. P. Candeth, commanding India's 17th Infantry Division, and as the very model of a modern major general, he betrayed no sign that he is finding Goans less than happy about their "liberation". Goan girls refuse to dance with Indian officers. Goan shops have been stripped bare by luxury-hungry Indian soldiers, and Indian import restrictions prevent replacement. Even in India, doubts are heard. "India", said respected Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, leader of the Swatantra Party, "has totally lost the moral power to raise her voice against the use of military power"— "Symbolic pose by Goa's Governor", Life International, 12 February 1962

United Kingdom

Commonwealth Relations Secretary, Duncan Sandys told the House of Commons on 18 December 1961 that while the UK Government had long understood the desire of the Indian people to incorporate Goa, Daman, and Diu in the Indian Republic, and their feeling of impatience that the Portuguese Government had not followed the example of Britain and France in relinquishing their Indian possessions, he had to "make it plain that H.M. Government deeply deplores the decision of the Government of India to use military force to attain its political objectives."

The Leader of the Opposition in the House of Commons Hugh Gaitskell of the Labour Party also expressed "profound regret" that India should have resorted to force in her dispute with Portugal, although the Opposition recognised that the existence of Portuguese colonies on the Indian mainland had long been an anachronism and that Portugal should have abandoned them long since in pursuance of the example set by Britain and France. Permanent Representative of the United Kingdom to the United Nations, Sir Patrick Dean, stated in the UN that Britain had been "shocked and dismayed" at the outbreak of hostilities.[54]

Netherlands

A Foreign Ministry spokesman in The Hague regretted that India, "of all countries," had resorted to force to gain her ends, particularly as India had always championed the principles of the U.N. Charter and consistently opposed the use of force to achieve national purposes. Fears were expressed in the Dutch Press lest the Indian attack on Goa might encourage Indonesia to make a similar attack on West New Guinea.[54] On 27 December 1961, Dutch ambassador to the United States, Herman Van Roijen asked the US Government if their military support in the form of the USN's 7th Fleet would be forthcoming in case of such an attack.[75]

Brazil

Brazil's reaction to the invasion of Goa was one of staunch solidarity with Portugal, reflecting earlier statements by Brazilian presidents that their country stood firmly with Portugal anywhere in the world and that ties between Brazil and Portugal were built on ties of blood and sentiment. Former Brazilian President Juscelino Kubitschek, and long time friend and supporter of Portuguese PM Salazar, stated to Indian PM Nehru that "Seventy Million Brazilians could never understand, nor accept, an act of violence against Goa." [76] In a speech in Rio de Janeiro on 10 June 1962, Brazilian congressman Gilberto Freyre commented on the invasion of Goa by declaring that "a Portuguese wound is Brazilian pain".[77]

Shortly after the conflict, the new Brazilian ambassador to India, Mario Guimarães, stated to the Portuguese ambassador to Greece that it was "necessary for the Portuguese to comprehend that the age of colonialism is over". Guimarães dismissed the Portuguese ambassador's argument that Portuguese colonialism was based on miscegenation and the creation of multiracial societies, stating that this was "not enough of a reason to prevent independence".[78]

Pakistan

In a statement released on 18 December, the Pakistani Foreign Ministry spokesman described the Indian attack on Goa as "naked militarism". The statement emphasised that Pakistan stood for the settlement of international disputes by negotiation through the United Nations and stated that the proper course was a "U.N.-sponsored plebiscite to elicit from the people of Goa their wishes on the future of the territory." The Pakistani statement (issued on 18 December) continued: "The world now knows that India has double standards…. One set of principles seem to apply to India, another set to non-India. This is one more demonstration of the fact that India remains violent and aggressive at heart, whatever the pious statements made from time to tune by its leaders.[54]

"The lesson from the Indian action on Goa is of practical interest on the question of Kashmir. Certainly the people of Kashmir could draw inspiration from what the Indians are reported to have stated in the leaflets they dropped… on Goa. The leaflets stated that it was India's task to ‘defend the honour and security of the Motherland from which the people of Goa had been separated far too long' and which the people of Goa, largely by their own efforts could again make their own. We hope the Indians will apply the same logic to Kashmir. Now the Indians can impress their electorate with having achieved military glory. The mask is off. Their much-proclaimed theories of non-violence, secularism, and democratic methods stand exposed."[54]

In a letter to the US President on 2 January 1962, Pakistani President General Ayub Khan stated: "My Dear President, The forcible taking of Goa by India has demonstrated what we in Pakistan have never had any illusions about—that India would not hesitate to attack if it were in her interest to do so and if she felt that the other side was too weak to resist."[79]

Ambivalent

The Catholic Church

The Roman Catholic Archbishop of Goa and Daman and Patriarch of the East Indies was always a Portuguese-born cleric; at the time of the annexation, José Vieira Alvernaz was archbishop, and days earlier Dom José Pedro da Silva had been nominated by the Holy See as coadjutor bishop with right to succeed Alvernaz. After the annexation, Silva remained in Portugal and was never consecrated; in 1965 he became bishop of Viseu in Portugal. Alvernaz retired to the Azores but remained titular Patriarch until resigning in 1975 after Portuguese recognition of the 1961 annexation.

Although the Vatican did not voice its reaction to the annexation of Goa, it delayed the appointment of a native head of the Goan Church until the inauguration of the Second Vatican Council in Rome, when Msgr Francisco Xavier da Piedade Rebelo was consecrated Bishop and Vicar Apostolic of Goa in 1963.[80][81] His was succeeded by Raul Nicolau Gonçalves in 1972, who became he first native-born Patriarch in 1978.[82]

Cultural depiction