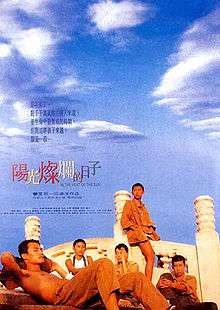

In the Heat of the Sun

| In the Heat of the Sun | |

|---|---|

| |

| Traditional | 陽光燦爛的日子 |

| Simplified | 阳光灿烂的日子 |

| Mandarin | Yángguāng cànlàn de rìzi |

| Literally | Days of the Bright and Lush Sunshine |

| Directed by | Jiang Wen |

| Produced by |

Guo Youliang Hsu An-chin Po Ki |

| Written by | Jiang Wen |

| Based on |

Wild Beast by Wang Shuo |

| Starring |

Xia Yu Ning Jing Geng Le Tao Hong |

| Music by | Guo Wenjing |

| Cinematography | Gu Changwei |

| Edited by | Zhou Ying |

Release dates | 1994 |

Running time | 134 minutes |

| Country | China |

| Language | Mandarin |

In the Heat of the Sun is a 1994 film directed and written by Jiang Wen. This was Jiang Wen's first foray into directing after years as a leading man. The film is based on author Wang Shuo's novel Wild Beast (动物凶猛).

Synopsis

The film is set in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution. It is told from the perspective of Ma Xiaojun nicknamed Monkey (played by Xia Yu; some of Monkey's experiences mimic director Jiang's during the Revolution[1]), who is a teenage boy at the time. Monkey and his friends are free to roam the streets of Beijing day and night because the Cultural Revolution has caused their parents and most adults to be either busy or away and school system was extremely nonfunctional during the Cultural Revolution. Jiang Wen cryptically suggested that famous movement during the Cultural revolution that most older young people were sent to the countryside. China was actively preparing for military due to the Vietnam War and claiming USSR to be revisionist. Since Monkey and his friends were military children, their parents were off for military purposes. Most of the story happens during one summer, so the main characters are even more free because there is no school. The events of that summer revolve around Monkey's dalliances with his roguish male friends, and his subsequent angst-filled crush on one of the female characters, Mi Lan (Ning Jing). However, Mi Lan falls in love with Monkey's friend, Liu Yiku.

This film is significant in its unique perspective on the Cultural Revolution. In contrast to the Cultural Revolution-set films of Chinese 5th-generation filmmakers (Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige, Tian Zhuangzhuang) which put the era into a larger historical setting, In The Heat Of the Sun is mellow and dream-like, portraying memories of that era with somewhat positive and personal resonances. It also acknowledges, as the narrator recalls, that he might have misremembered parts of his adolescence as stated in the prologue: "Change has wiped out my memories. I can't tell what's imagined from what's real",[2] as the director offers alternative or imagined versions to some events as people seek to romanticize their youthful memories. Critic Raymond Zhou talked about this ambiguity in Jiang Wen's movie: "Ambiguity is a major characteristic. Since two of his four features wax nostalgic about the 'cultural revolution' (1966-76), a period that evokes painful memories for many Chinese…" [3]Because of ambiguity of In the Heat of the Sun, Jiang Wen made his film politically acceptable to censors in 1990s. Though in many details, the movie reflects typical historical phenomenon of Cultural Revolution, Jiang Wen did not explicitly mention any specific event during the Cultural Revolution. That was why this movie was the one and only movie about the Cultural Revolution passed the censors during 1990s.

Development

The film was a co-production of three Chinese studios, and $2 million USD (about $3198473.28 when adjusted for inflation) of the budget was generated from Hong Kong. Derek Elley of Variety said that the film alters "some 70% of the original" novel and adds "a mass of personal memories."[4] Daniel Vukovich, author of China and Orientalism: Western Knowledge Production and the PRC, wrote that the film version makes its characters "a small group of male friends, plus one female "comrade"" instead of being "violent hooligans".[5]

The original title of film may be translated as "Bright Sunny Days". In the Heat of the Sun was chosen as its international English title for the film during a film festival in Taiwan as a less politicized name to avoid the original title's positive association of the period during the Cultural Revolution.[6]

Cast

- Han Dong - Ma Xiaojun (S: 马小军, T:馬小軍, P: Mǎ Xiǎojūn, young boy)

- Xia Yu - Ma Xiaojun (teenage Monkey). Wendy Larson, author of From Ah Q to Lei Feng: Freud and Revolutionary Spirit in 20th Century China, wrote that the selection of "an awkward-looking boy" who "contrasts with the more conventional tall good looks" of Liu Yiku was clever on part of Jiang Wen, and that Xia Yu "portrays [Ma Xiaojun] as charmingly shy and mischievous in social relationships yet forceful and engaging in his emotions."[7] The character has the nickname "Monkey" in the film version. "Monkey" was the nickname of director Jiang Wen.[4] Derek Elley of Variety says that Xia as Xiaojun has "both an uncanny resemblance to Jiang himself and a likable combination of insolence and innocence."[4]

- Feng Xiaogang - Mr. Hu (S: 胡老师, T: 胡老師, Hú-lǎoshī), the teacher

- Geng Le - Liu Yiku (S: 刘忆苦, T: 劉憶苦, P: Liú Yìkǔ, teenage)

- Jiang Wen - Ma Xiaojun (adult; narrator)

- Ning Jing - Mi Lan (S: 米 兰, T: 米 蘭, P: Mǐ Lán)

- Tao Hong - Yu Beibei (于北蓓 Yú Běibèi). In the beginning Yu Beibei accompanies the boys and gives rise to sexual tension amongst them, but after Mi Lan is introduced, Yu Beibei does not appear with the group until the second telling of the birthday party. Larson states that Yu Beibei "is a significant character" in the first part of the film and that her disappearance is a "persistent clue that all is not as it seems".[8]

- Shang Nan - Liu Sitian (S: 刘思甜, T:劉思甜, P: Liú Sītián)

- Wang Hai - Big Ant

- Liu Xiaoning - Liu Yiku (adult)

- Siqin Gaowa - Zhai Ru (翟 茹 Zhái Rú - Xiaojun's mother)

- Wang Xueqi - Ma Wenzhong (S: 马文中, T:馬文中, P: Mǎ Wénzhōng - Xiaojun's father)

- Fang Hua - Old general

- Dai Shaobo - Yang Gao (羊搞 Yáng Gǎo)

- Zuo Xiaoqing – Zhang Xiaomei

Jiang Wen cast 3 youngsters with no acting experience but with notable athletic experience: Xia Yu was the skateboarding champion in his hometown Qingdao, Tao Hong was a synchronized swimmer on the Chinese national team, while Zuo Xiaoqing was a rhythmic gymnast also on the Chinese national team. All three enrolled in professional acting schools within a year of the film's release (Xia and Tao went to Jiang's alma mater Central Academy of Drama, while Zuo was accepted to Beijing Film Academy) and became successful actors.

Music

The Chinese version of the Soviet song "Moscow Nights" features prominently in the film, as does Pietro Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana.

Reception

The film was commercially successful in China. Vukovich wrote that the film however did cause some controversy in China for its perceived "nostalgic" and "positive" portrayal of the Cultural Revolution.[9]

According to Vukovich, the film "received much less attention than any fifth-generation classics" despite the "critical appreciation in festivals abroad".[9] Vukovich stated that in Western countries "the film has been subjected to an all too familiar coding as yet another secretly subversive, dissenting critique of Maoist and Cultural Revolution totalitarianism",[9] with the exceptions being the analyses of Chen Xiaoming from Mainland China and Wendy Larson.[9]

Awards and recognition

Very well received in China and the Chinese-speaking world but very obscure in the United States, the film won the 51st Venice Film Festival's Best Actor Award for its young lead actor Xia Yu (Xia was then the youngest recipient of the Best Actor award at Venice) as well as the Golden Horse Film Awards for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor. American director Quentin Tarantino also gave high praises to the film, calling it "really great."[10]

It was the first People's Republic of China film to win Best Picture in the Golden Horse Film Awards, in the very year where a liberalization act allows Chinese-language films from the mainland to participate.

References

- Larson, Wendy. From Ah Q to Lei Feng: Freud and Revolutionary Spirit in 20th Century China. Stanford University Press, 2009. ISBN 0804769826, 9780804769822.

- Vukovich, Daniel. China and Orientalism: Western Knowledge Production and the PRC (Postcolonial Politics). Routledge, June 17, 2013. ISBN 113650592X, 9781136505928.

Notes

- ↑ "Interview with Jiang Wen." CNN. July 23, 2007. Retrieved on September 19, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.chinesecinemas.org/intheheat.html

- ↑ http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/life/2011-02/23/content_12062593.htm

- 1 2 3 "In the Heat of the Sun." Variety. Sunday October 16, 1994. Retrieved on September 23, 2011.

- ↑ Vukovich, p. 149.

- ↑ Vukovich, page unstated (Google Books p. PT151).

- ↑ Larson, p. 174 (Google Books PT187).

- ↑ Larson, p. 177 (Google Books PT190).

- 1 2 3 4 Vukovich, page unstated (Google Books PT148).

- ↑ Quentin Tarantino Interview - KILL BILL And Others by New Cinema Magazine.

Further reading

- Qi Wang. "Writing Against Oblivion: Personal Filmmaking from the Forsaken Generation in Post-socialist China." (dissertation) ProQuest, 2008. ISBN 0549900683, 9780549900689. p. 149-152.

- Silbergeld, Jerome (2008), Body in Question: Image and Illusion in Two Chinese Films by Director Jiang Wen (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

- Su, Mu (Beijing Film Academy). Sunny Teenager: A Review of the Movie in the Heat of the Sun. Strategic Book Publishing, 2013. ISBN 1625165080, 9781625165084. See page at Google Books.

External links

- In The Heat Of The Sun at the Internet Movie Database

- In the Heat of the Sun at AllMovie

- Braester, Yomi. "Memory at a standstill: 'street-smart history' in Jiang Wen's In the Heat of the Sun." Screen 42:4 Winter 2001.

- Lu, Tonglin. "Fantasy and Ideology in a Chinese Film: A Žižekian Reading of the Cultural Revolution." Project MUSE. (pdf version)

- Williams, Louise. "Men in the Mirror : Questioning Masculine Identities in In the Heat of the Sun." China Information 2003 17: 92 doi:10.1177/0920203X0301700104. (Archive)

- "In The Heat of The Sun, directed by Jiang Wen, China 1994." (Archive). Wooster University.

- (hk) 陽光燦爛的日子 at the Hong Kong Movie Database, hkmd.com Inc

- "A truth that's stranger than fiction."