Illyria

| Illyria | |

|---|---|

| Historical region | |

.svg.png) Approximate area settled by Illyrians in antiquity. | |

| Area | W Balkan Peninsula |

In classical antiquity, Illyria (Ancient Greek: Ἰλλυρία or Ἰλλυρίς,[1] Latin: Illyria,[2] see also Illyricum) was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by the Illyrians.

The prehistory of Illyria and the Illyrians is known from archaeological evidence. The Romans conquered the region in 168 BC in the aftermath of the Illyrian Wars.

The Roman term Illyris (distinct from Illyria) was sometimes used to define an area north of the Aous valley, most notably Illyris proper.[3]

Name

In Greek mythology, the name of Illyria is aetiologically traced to Illyrius, the son of Cadmus and Harmonia, who eventually ruled Illyria and became the eponymous ancestor of the Illyrians.[4] A later version of the myth identifies Polyphemus and Galatea as parents of Celtus, Galas and Illyrius.[5]

Ancient Greek writers used the name "Illyrian" to describe peoples between the Liburnians and Epirus.[6] 4th-century BC Greek writers clearly separated the people along the Adriatic coast from the Illyrians, and only in the 1st century AD was "Illyrian" used as a general term for all the peoples across the Adriatic.[7] Writers also spoke of "Illyrians in the strict sense of the word"; Pomponius Mela (43 AD) the stricto sensu Illyrians lived north of the Taulanti and Enchele, on the Adriatic shore;[8] Pliny the Elder used "properly named Illyrians"[7] (Illyrii proprii/proprie dicti) for a small people[7] south of Epidaurum,[7] or between Epidaurum (now Cavtat) and Lissus (now Lezhë).[8] In the Roman period, Illyricum was used for the area between the Adriatic and Danube.[6] The term was in a way of pars pro toto.[9]

Kingdoms

The earliest recorded Illyrian kingdom was that of the Enchele in the 8th century BC.[10] The era in which we observe other Illyrian kingdoms begins approximately at 400 BC and ends at 167 BC.[11] The Autariatae under Pleurias (337 BC) were considered to have been a kingdom.[12] The Kingdom of the Ardiaei began at 230 BC and ended at 167 BC.[13] The most notable Illyrian kingdoms and dynasties were those of Bardyllis of the Dardani and of Agron of the Ardiaei who created the last and best-known Illyrian kingdom.[14] Agron ruled over the Ardiaei and had extended his rule to other tribes as well.[15] As for the Dardanians, they always had separate domains from the rest of the Illyrians.[16]

The Illyrian kingdoms were composed of small areas within the region of Illyria. Only the Romans ruled the entire region. The internal organization of the south Illyrian kingdoms points to imitation of their neighbouring Greek kingdoms and influence from the Greek and Hellenistic world in the growth of their urban centres.[17] Polybius gives as an image of society within an Illyrian kingdom as peasant infantry fought under aristocrats which he calls in Greek Polydynastae (Greek: Πολυδυνάστες) where each one controlled a town within the kingdom.[18] The monarchy was established on hereditary lines and Illyrian rulers used marriages as a means of alliance with other powers.[19] Pliny (23–79 AD) writes that the people that formed the nucleus of the Illyrian kingdom were 'Illyrians proper' or Illyrii Proprie Dicti.[20] They were the Taulantii, the Pleraei, the Endirudini, Sasaei, Grabaei and the Labeatae. These later joined to form the Docleatae.

Roman and Byzantine rule

The Romans defeated Gentius, the last king of Illyria, at Scodra (in present-day Albania) in 168 BC and captured him, bringing him to Rome in 165 BC. Four client-republics were set up, which were in fact ruled by Rome. Later, the region was directly governed by Rome and organized as a province, with Scodra as its capital.

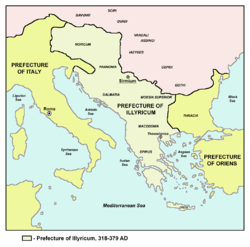

The Roman province of Illyricum replaced the formerly independent kingdom of Illyria. It stretched from the Drilon river in modern Albania to Istria (Croatia) in the west and to the Sava river (Bosnia & Herzegovina) in the north. Salona (near modern Split in Croatia) functioned as its capital.

After crushing a revolt of Pannonians and Daesitiates, Roman administrators dissolved the province of Illyricum and divided its lands between the new provinces of Pannonia in the north and Dalmatia in the south. Although this division occurred in 10 AD, the term Illyria remained in use in Late Latin and throughout the medieval period. After the division of the Roman Empire, the bishops of Thessalonica appointed papal vicars for Illyricum. The first of these vicars is said to have been Bishop Acholius or Ascholius (died 383 or 384), the friend of St. Basil. In the 5th century, the bishops of Illyria withdrew from communion with Rome, without attaching themselves to Constantinople, and remained for a time independent, but in 515, forty Illyrian bishops renewed their loyalty to Rome by declaring allegiance to Pope Hormisdas. The patriarchs of Constantinople succeeded in bringing Illyria under their jurisdiction in the 8th century.[21]

Legacy

The name Illyria only disappears from the historical record after the Ottoman invasion of the Balkans in the 15th century, and re-emerges in the 17th century, acquiring a new significance in the Ottoman–Habsburg Wars, as Leopold I designated as the "Illyrian nation" the South Slavs in Hungarian territory.[21] Several armorials of the Early modern period, popularly called the "Illyrian Armorials", depicted fictional coats of arms of Illyria.

The name Illyria was revived by Napoleon for the Illyrian Provinces that were incorporated into the French Empire from 1809 to 1813, and the Kingdom of Illyria (1816–1849) was part of Austria until 1849, after which time it was not used in the reorganised Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The Illyrian movement was a pan-South Slavist (Yugoslavism) cultural and political campaign by a group of young Croatian intellectuals during the first half of the 19th century.

In popular culture

William Shakespeare chose a fictionalised Illyria as the setting for his play Twelfth Night (In the modernised film spoof She's the Man, this function is served by "Illyria High School" in California). An extensive history of Illyria by Charles du Fresne, sieur du Cange, was published by Joseph Keglevich in 1746.[22] Shakespeare also mentioned the region in the Part 2 of the play Henry VI.[23]

The land of Illyria is the setting for Jean-Paul Sartre's Les Mains Sales and in Lloyd Alexander's The Illyrian Adventure.

John Hawkes 1970 novel The Blood Oranges is set in a fictionalised Illyria reminiscent of Shakespeare's.

In Christopher Paolini's Inheritance Cycle, Illyria is the former name of an Elven city north of Lake Tudosten. It was later renamed Urû'baen when captured by Galbatorix and the Forsworn.

In the Television show Angel, Illyria was the name of an Old One (an ancient and powerful demon) who was resurrected in the final season.

In Jacqueline Carey's book Kushiel's Chosen, Illyria is featured as a vassal nation to La Serenissima (Venice).

See also

- Dalmatia

- Diocese of Illyricum

- History of the Balkans

- Illyrian Provinces

- Illyrian warfare

- Kingdom of Illyria (1816–1849)

- Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum

- Illyricum (Roman province)

References

Citations

- ↑ Polybius. Histories, 1.13.1.

- ↑ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles. "Illyria". A Latin Dictionary.

- ↑ Boardman 1982, p. 623.

- ↑ Grimal & Maxwell-Hyslop 1996, p. 230.

- ↑ Grimal & Maxwell-Hyslop 1996, p. 168

- 1 2 Wilks 1969, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilks 1969, p. 161.

- 1 2 Radoslav Katicic (1 January 1976). Ancient Languages of the Balkans. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-3-11-156887-4.

- ↑ Marjeta Šašel Kos (2005). Appian and Illyricum. Narodni Muzej Slovenije. p. 231. ISBN 978-961-6169-36-3.

- ↑ Stipčević 2002, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 298.

- ↑ Lewis & Boardman 1994, p. 785.

- ↑ Wilkes 1969, p. 13.

- ↑ Kipfer 2000, p. 251.

- ↑ Hammond 1993, p. 104.

- ↑ Papazoglu 1978, p. 216.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 237.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 127.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 167.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 216.

- 1 2 Lins 1910, "Illyria".

- ↑ du Fresne 1746, p. 1.

- ↑ "Henry VI, part 2: Entire Play". shakespeare.mit.edu.

Sources

- Berranger, Danièle; Cabanes, Pierre; Berranger-Auserve, Danièle (2007). Épire, Illyrie, Macédoine: Mélanges Offerts au Professeur Pierre Cabanes. Clermont-Ferrand, France: Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal. ISBN 2-84516-351-7.

- Boardman, John (1982). The Prehistory of the Balkans and the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries B.C. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22496-9.

- du Fresne, Charles (1746). Illyricvm Vetvs & Novum: Sive Historia Regnorvm Dalmatiae, Croatiae, Slavoniae, Bosniae, Serviae, atqve Bvlgariae. Posonii: Typis Haeredvm Royerianorvm.

- Grimal, Pierre; Maxwell-Hyslop, A. R. (1996). The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 0-631-20102-5.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1993). Studies concerning Epirus and Macedonia before Alexander. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Adolf M. Hakkert.

- Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. New York, New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. ISBN 0-306-46158-7.

- Lewis, David Malcolm; Boardman, John (1994). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 6: The Fourth Century BC. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23348-8.

- Lins, Joseph (1910). "Illyria". The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume 7. New York, New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Papazoglu, Fanula (1978). The Central Balkan Tribes in Pre-Roman Times: Triballi, Autariatae, Dardanians, Scordisci and Moesians. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Adolf M. Hakkert. ISBN 90-256-0793-4.

- Stipčević, Aleksandar (2002). Ilirët: Historia, Jeta, Kultura, Simbolet e Kultit. Tirana, Albania: Toena. ISBN 99927-1-609-6.

- Wilkes, John J. (1969). History of the Provinces of the Roman Empire. London, United Kingdom: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Wilkes, John J. (1995). The Illyrians. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishers Limited. ISBN 0-631-19807-5.

External links

Media related to Illyria and Illyrians at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Illyria and Illyrians at Wikimedia Commons