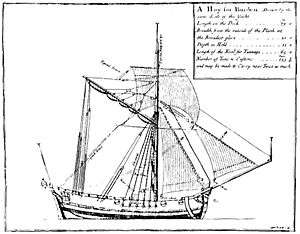

Hoy (boat)

A hoy was a small sloop-rigged coasting ship or a heavy barge used for freight, usually with a burthen of about 60 tons (bm). The word derives from the Middle Dutch hoey. In 1495, one of the Paston Letters included the phrase, An hoye of Dorderycht (a hoy of Dordrecht), in such a way as to indicate that such contact was then no more than mildly unusual. The English term was first used on the Dutch Heude-ships that entered service with the British Royal Navy.

Evolution and use

Over time the hoy evolved in terms of its design and use. In the fifteenth century a hoy might be a small spritsail-rigged warship like a cromster. Like the earlier forms of the French chaloupe, it could be a heavy and unseaworthy harbour boat or a small coastal sailing vessel (latterly, the chaloupe was a pulling cutter – nowadays motorized). By the 18th and 19th Century hoys were sloop-rigged and the mainsail could be fitted with or without a boom. English hoys tended to be single-masted, whereas Dutch hoys had two masts. Principally, and more so latterly, the hoy was a passenger or cargo boat. For the English, a hoy was a ship working in the Thames Estuary and southern North Sea in the manner of the Thames sailing barge of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the Netherlands a slightly different vessel did the same sort of work in similar waters. Before the development of steam engines, the passage of boats in places like the Thames estuary and the estuaries of the Netherlands, required the skillful use of tides as much as of the wind.

Hoys also would carry cargo or passengers to the larger ships anchored in the Thames. The British East India Company used hoys as lighters for larger ships that could not travel up the Thames to London. These were commonly referred to as East India hoys.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, English hoys plied a trade between London and the north Kent coast that enabled middle class Londoners to escape the city for the more rural air of Margate, for example.[2] Others sailed between London and Southampton. These were known as Margate or Southampton hoys and one could hail them from the shore to pick up goods and passengers.

The introduction of the early steamers greatly expanded this sort of trade. At the same time, barges were taking over the cargo coasting trade on the short routes. Together, these developments meant that hoys fell out of use.

Royal Navy

The British Royal Navy used hoys that were specially built to carry fresh water, gunpowder or ballast. Some were employed in such tasks as laying buoys or survey work, while others served to escort coastal convoys. Still others were in the Revenue service.

In 1793–94 the Royal Navy purchased 19 Dutch hoys as coastal gun-vessels, particularly for service under Admiral Sir Sidney Smith. In naval service these had 30-man crews and each carried one 24-pounder gun and three 32-pounder carronades.[3] Examples include HMS Scourge and HMS Shark (Shark's crew mutinied in 1795 and handed her over to the French). Around the end of the French Revolutionary Wars, the Navy sold its remaining armed hoys.

Concern about a possible French invasion led the Royal Navy on 28 September 1804 to arm 16 hoys at Margate for the defense of the coast. One of these bore the name King George. The Navy manned each hoy with a captain and nine men from the Sea Fencibles.[4] The same concern also led the British to build over a hundred Martello towers along the British and Irish coasts.

Because most hoys were merchantmen, they were also frequently taken as prizes during time of war. Many of the hoys in British naval service had been captured from enemies. One of the earliest on record was the Mary Grace, captured in 1522 and listed until 1525.

See also

- On the French coast, a similar but generally faster vessel type, which continued its development until later, was known as the chasse-marée. Its centre of operations was the Breton coast and it specialized in carrying fresh sea fish to market. It was normally rigged as a three-masted lugger.

Footnotes

- ↑ Sutherland 1717, facing p. 17.

- ↑ Whyman 1993.

- ↑ Winfield 2008, pp. 324–5.

- ↑ The Naval chronicle, Volume 12, p.329,

References

- Sutherland, William (1717), Britain's Glory, or Shipbuilding Unvail'd, Clarke, OCLC 731314497

- Whyman, John (1993), "The significance of the hoy to Margate's early growth as a seaside resort" (PDF), Archaeologia Cantiana, 111: 17–41, ISSN 0066-5894, archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2015, retrieved 3 June 2015

- Winfield, Rif (2008), British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates, Seaforth, ISBN 1-86176-246-1

Gallery

-

East Indiaman and hoys off Dordrecht, Albert Cuyp, (17th century)

-

Shipping off Woolwich, Thomas Mellish, 1748, National Maritime Museum. The vessel in the left foreground is a hoy.