Honorary citizen of the United States

A person of exceptional merit, generally a non-United States citizen, may be declared an honorary citizen of the United States by an Act of Congress or by a proclamation issued by the President of the United States, pursuant to authorization granted by Congress.

Eight people have been so honored, six posthumously, and two, Sir Winston Churchill and Mother Teresa, during their lifetimes.

Recipients

| Number | Name | Image | Award date | Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

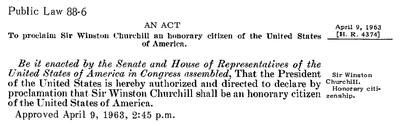

| 1 | Sir Winston Churchill |  |

1963 | Prime Minister of the United Kingdom[2][3] |

| 2 | Raoul Wallenberg |  |

1981 (awarded posthumously) |

Swedish diplomat who rescued Jews from the Holocaust[4] |

| 3 and 4 | William Penn |  |

28 Nov 1984 (awarded posthumously) |

Founder of the Province of Pennsylvania[5][6] |

| Hannah Callowhill Penn |  |

Administrator of the Province of Pennsylvania, second wife of William Penn[5][6] | ||

| 5 | Mother Teresa |  |

1996 | Catholic nun of Albanian ethnicity and Indian citizenship, who founded the Missionaries of Charity in Calcutta[7] |

| 6 | Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette |  |

2002 (awarded posthumously) |

A Frenchman who was an officer in the American Revolutionary War |

| 7 | Casimir Pulaski | 2009 (awarded posthumously) |

Polish military officer who fought and died for the United States against the British during the American Revolutionary War; notable politician and member of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth nobility, American Brigadier General who has been called "The Father of the American Cavalry" and died during the Siege of Savannah (South Carolina). Remembered as a national hero both in Poland and in the United States of America.[8][9][10][11] | |

| 8 | Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Viscount of Galveston and Count of Gálvez |  |

2014 (awarded posthumously) |

A Spaniard who was a hero of the American Revolutionary War who risked his life for the freedom of the United States people and provided supplies, intelligence, and strong military support to the war effort, who was wounded during the Siege of Pensacola, demonstrating bravery that forever endeared him to the United States soldiers.[12] The King of Spain Carlos III granted him the right to the motto YO SOLO (I ALONE) for his coat of arms |

For Lafayette and Mother Teresa, the honor was proclaimed directly by an Act of Congress. In the other cases, an Act of Congress was passed authorizing the President to grant honorary citizenship by proclamation.

Legal issues

What rights and privileges honorary citizenship bestows, if any, is unclear. According to State Department documents, it does not grant eligibility for United States passports.[1]

Despite widespread belief that Lafayette received honorary citizenship of the United States before Churchill,[13] he did not receive honorary citizenship until 2002. Lafayette did become a natural-born citizen during his lifetime. On 28 December 1784, the Maryland General Assembly passed a resolution stating that Lafayette and his male heirs "forever shall be...natural born Citizens" of the state.[14] This made him a natural-born citizen of the United States under the Articles of Confederation and as defined in Section 1 of Article Two of the United States Constitution.[15][16][13][17][18][2]

Lafayette boasted in 1792 that he had become an American citizen before the French Revolution created the concept of French citizenship.[19] In 1803, President Jefferson wrote him he would have offered to make him Governor of Louisiana, had he been "on the spot".[20] In 1932, descendant René de Chambrun established his American citizenship based on the Maryland resolution,[21][22] although he was probably ineligible as the inherited citizenship was likely only intended for direct descendants who were heir to Lafayette's estate and title.[23] The Board of Immigration Appeals ruled in 1955 that "it is possible to argue" that Lafayette and living male heirs became American citizens when the Constitution became effective on 4 March 1789, but that heirs born later were not US citizens.[16]

Honorary citizenship should not be confused with citizenship or permanent residency bestowed by a private bill. Private bills are, on rare occasions, used to provide relief to individuals, often in immigration cases, and are also passed by Congress and signed into law by the President. One such statute, granting Elián González US citizenship, was suggested in 1999, but was never enacted.[24]

See also

References

- 1 2 "7 FAM 1170: Honorary Citizenship". Foreign Affairs Manual Volume 7 – Consular Affairs. U.S. Department of State. 9 April 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- 1 2 Plumpton, John (Summer 1988). "A Son of America Though a Subject of Britain". Finest Hour. The Churchill Centre (60).

- ↑ "Winston Churchill" (PDF). Pub.L. 86-6. U.S. Senate. 9 April 1963. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ "Raoul Wallenberg" (PDF). Pub.L. 97-54, 95 Stat. 971. U.S. Senate. 5 October 1981. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- 1 2 "William Penn and Hannah Callowhill Penn" (PDF). Pub.L. 98-516, 98 Stat. 2423. U.S. Senate. 19 October 1984. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- 1 2 "Proclamation 5284 -- Honorary United States Citizenship for William and Hannah Penn". Proclamation 5284. Reagan Presidential Library. 28 November 1984. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ↑ H.J. Res. 191 (Pub.L. 104–218, 110 Stat. 3021, enacted October 1, 1996)

- ↑ "Casimir Pulaski Day". Office of Civil Rights and Diversity at Eastern Illinois University. 2005. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ Richmond, Yale (1995). From Da to Yes: Understanding the East Europeans. Yarmouth, Me: Intercultural Press. p. 72. ISBN 1-877864-30-7.

- ↑ "Citizenship for Polish Hero of American Revolution". The New York Times. Associated Press. 7 November 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

Gen. Casimir Pulaski finally became an American citizen, 230 years after he died fighting in the Revolutionary War.

- ↑ H.J. Res. 26 (S.J. Res. 12) (Pub.L. 111–94, 123 Stat. 2999, enacted November 6, 2009)

- ↑ Galvez, Bernardo. "H.J. Res. 105 Engrossed in House (EH)". US Congress. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Sir Winston May Get U.S. Citizenship". Sarasota Journal. UPI. 1963-03-11. p. 5. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ Lafayette again became an honorary citizen of Maryland in 1823, as well as of Connecticut the same year.

- ↑ Speare, Morris Edmund (7 September 1919). "Lafayette, Citizen of America". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- 1 2 IN THE MATTER OF M, 6 IN Dec. 749 (B.I.A. 1955) (“We need not consider the precise effect of the Maryland act of 1784 upon the political status of Lafayette and such of his male heirs as had been born prior to the date when the Constitution of the United States became effective (March 4, 1789). It is possible to argue that they were citizens of Maryland and under Section 2 of Article IV of the United States Constitution should be considered citizens of the United States. However, we hold that when Congress by legislation set forth the requirements for citizenship, the descendents of Lafayette who were born thereafter could only acquire United States citizenship on the terms specified by Congress, and they were not in a position to acquire such citizenship by virtue of the Maryland act of 1784.”).

- ↑ Folliard, Edward T. (25 May 1973). "JFK Slipped on Historical Data In Churchill Tribute". Sarasota Journal. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ Cornell, Douglas B. (10 April 1963). "Churchill Acceptance 'Honors Us Far More'". The Sumter Daily Item. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ "Lafayette: Citizen of Two Worlds". Lafayette: Citizen of Two Worlds. Cornell University Library. 2006. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- ↑ "Lafayette's Triumphal Tour: America, 1824-1825". Lafayette: Citizen of Two Worlds. Cornell University Library. 2006. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ "Letters". TIME. 2 December 1940. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ Rogister, John (17 August 2002). "Obituaries: René de Chambrun". The Independent. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ Gottschalk, Louis Reichenthal (1950). Lafayette Between the American and the French Revolution (1783-1789). University of Chicago Press. pp. 435–436.

- ↑ Bash, Dana (23 December 1999). "Helms says he aims to offer U.S. citizenship to Elian Gonzalez". CNN. Retrieved 2 February 2011.