Hogtown, Florida

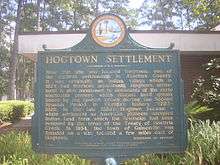

Hogtown was a 19th-century settlement in and around what is now Westside Park in Gainesville, Florida, United States (in the northeast corner of the intersection of NW 8th Avenue and 34th Street) where a historical marker[1][2][3] notes Hogtown's location at that site and is the eponymous outpost of the adjacent Hogtown Creek. Originally a village of Seminoles who raised hogs, the habitation was dubbed "Hogtown" by nearby white people who traded with the Seminoles. Indian artifacts were found at Glen Springs, which empties into Hogtown Creek.[4] In 1824, Hogtown's population was 14. After the acquisition of Florida by the United States, white settlers began moving into the area. The 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek obliged the Seminoles to move to a reservation in central Florida. Under the terms of the treaty, Chief John Mico received $20 as compensation for the "improvements" the Seminoles had made in Hogtown.[5][6]

The 1832 Treaty of Payne's Landing required the Seminoles in Florida to move to west of the Mississippi River after three years. Most of the Seminoles did not want to leave Florida. As the deadline for the start of the removal approached, tensions increased in Florida. In June 1835 there occurred an incident called the "Murder of Hogtown" (not to be confused with a work of fiction so titled[7]): A party of seven or eight Seminoles hunting off of the reservation had killed a cow and then made camp near Hogtown. A group of whites found five or six of the Seminoles at their camp, seized their weapons, and began whipping the Seminoles. The other two Seminoles returned to the camp, and seeing their fellows being whipped, opened fire on the whites. In the ensuing fight, three of the whites were wounded, one Seminole was killed, and another Seminole was reported to have been mortally wounded. Indian Agent Wiley Thompson demanded the surrender of the surviving Seminoles, and they were turned over to government custody for trial. There is no record of a trial occurring, however, reportedly because the whites involved did not want their actions examined in court. In August, Private Kinsley Dalton was killed while carrying the mail from Fort Brooke (Tampa) to Fort King (Ocala), allegedly in retaliation for the Seminoles killed at Hogtown.[8][9][10]

The Second Seminole War started late in December 1835, when 107 United States Army troops were killed by Seminoles in the Dade Massacre. White settlers throughout Florida left their homes or took steps to protect themselves. The residents of Hogtown built a fortification called Fort Hogtown, and were part of the Spring Grove Guards (Spring Grove was about 4 miles (6 km) west of Hogtown).[11][12]

In 1853, the residents of Alachua County realized that the route of the planned Florida Railroad would bypass the county seat, Newnansville. A general meeting at Boulware Springs was called to consider moving the county seat to a new town on the expected route of the railroad. William Lewis, who owned a plantation in Hogtown, offered 20 votes pledged to him in support of a new town on the railroad, with a deal that the town would be called Lewisville if it did not become the county seat. Lewis did not believe that there would be enough votes to move the county seat. However, Tillman Ingram, another plantation owner in Hogtown who also owned a sawmill there, offered to build a courthouse in the new town for such a favorable price that the move was approved. The name "Gainesville" was then chosen for the new town. Ingram built Oak Hall, said to be the first important house in downtown Gainesville, as well as the first courthouse. Lumber from the Hogtown mill had also been used for the oldest house in Gainesville, the Bailey House, built on the Bailey Plantation before Gainesville was established.[13][14]

An 1855 map of Hogtown and Gainesville is found on the site of the Alachua County Library District.[15]

In 1961, the City of Gainesville annexed the former site of Hogtown.[13][16][17] Colloquially, "Hogtown" is oft used as a synonym for Gainesville,[18] and many Gainesville businesses and events identify themselves as "Hogtown".

Citations

- ↑ Boone, Floyd E. (1988), Florida Historical Markers & Sites: A Guide to More Than 700 Historic Sites Includes the Complete Text of Each Marker, Houston, Texas, USA: Gulf Publishing Company, pp. 17–18, ISBN 0-87201-558-0

- ↑ "Historical Markers in Alachua County, Florida -- HOGTOWN SETTLEMENT / FORT HOGTOWN", Retrieved 2011-06-27

- ↑ "Historic Markers Across Florida -- Hogtown settlement / Fort Hogtown", Retrieved 2011-06-27

- ↑ Amy Grossman, Beth Zavoyski. "Glen Springs Restoration Plan" (PDF). October, 2012. Florida Springs Institute. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ Andersen:74

- ↑ Rajtar:15-16

- ↑ Abrams, Marjorie D. (2009), Murder on Hogtown Creek — A North Florida Mystery, Bangor, Maine, USA: BookLocker.com, Inc., ISBN 978-1-60910-012-4

- ↑ Drake:414, 470

- ↑ Missal:86-92

- ↑ Homan, Benjamin (September 17, 1835). "St. Augustine, Aug. 27". Army and Navy Chronicle. 1 (38): 304. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ↑ Rajtar:17

- ↑ Roberts:173-74

- 1 2 Hildreth and Cox:2-3

- ↑ Rajtar:15, 59, 133

- ↑ "Map of Hogtown and Gainesville, 1855". Heritage Collection. Alachua County Library District. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- ↑ "Annexation History". City of Gainesville. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- ↑ Rajtar:15-16, 59, 133

- ↑ Rajtar:15

References

- Andersen, Lars (2004). Paynes Prairie: the great savanna : a history and guide. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press. ISBN 1-56164-296-7.

- Rajtar, Steve (2007). A Guide to Historic Gainesville. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-217-8.

- Missal, John; Mary Lou Missal (2004). The Seminole Wars: America's Longest Indian Conflict. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2715-2.

- Drake, Samuel Gardner (1880). The aboriginal races of North America : comprising biographical sketches of eminent tribes, from the first discovery of the continent to the present period; with a dissertation on their origin, antiquities, manners and customs. New York: Hurst & Company.

- Roberts, Robert B. (1988). Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: the Military, Pioneer and Trading Posts of the United States. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 0-02-926880-X.

Coordinates: 29°38′53″N 82°19′29″W / 29.64797°N 82.32464°W