History of the Pike Place Market

The Pike Place Market in Seattle, Washington was founded in 1907. It is one of the longest continually run farmer's markets in the United States.

Before the Market

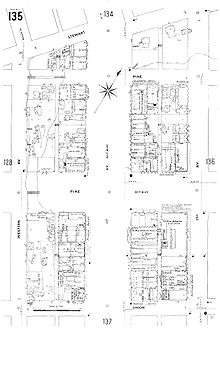

%3B_398%2C_296382125102001_602.jpg)

Before the creation of the Pike Place Market in 1907, local Seattle area farmers sold their goods to the public in a three-square block area called The Lots, located at Sixth Avenue and King Street. Most produce sold at The Lots would then be brought to commercial wholesale houses on Western Avenue, which became known as Produce Row. Most farmers, due to the amount of time required to work their farms, were forced to sell their produce on consignment through the wholesalers on Western Avenue. The farmers typically received a percentage of the final sale price for their goods. They would sell to the middleman on commission, as most farmers would often have no time to sell direct to the public, and their earnings would be on marked up prices and expected sales. In some cases, the farmers made a profit, but just as often found themselves breaking even, or getting no money at all due to the business practices of the wholesalers. During the existence of the wholesale houses, which far predated the Market, there were regular rumors as well as instances of corruption in denying payment to farmers.[1]

Consumers were also unhappy with the system. Manipulated prices often forced them to pay unexpectedly high prices for staple foods. For example, in 1906 and 1907, the price of food skyrocketed mysteriously. Onion prices climbed from 10 cents a pound in 1906 to a dollar a pound in 1907 (from US$0.10 to $1.00).[2] By comparison, a pair of shoes cost $2.00 at the time.[3]

Founding

As consumers and farmers grew increasingly vocal in their unhappiness over the situation, Thomas P. Revelle, a Seattle city councilman, lawyer, and newspaper editor, took advantage of an 1896 Seattle city ordinance that allowed the city to designate tracts of land as public markets. The area of Western Avenue above the Elliott Bay tideflats and the area of the commission food houses had just been turned into a wooden planked road, called Pike Place, off of Pike Street and First Avenue. Through a city council ordinance vote, he had Pike Place designated temporarily as the city's first public market on August 5, 1907.[4]

On Saturday, August 17, 1907 City Council President Charles Hiram Burnett Jr., filling in for the elected mayor as acting mayor of Seattle, declared the day Public Market Day and cut the ribbon.[3] In the week leading up to the opening of the Pike Place Market, various rumors and stories of further corruption were reported by the Seattle Times.[5] Roughly ten farmers pulled up their wagons on a boardwalk adjacent to the Leland Hotel.[6] The Times alleged several reasons for the low turnout of farmers: Western Avenue wholesale commission men who had gone to the nearby valleys and farms to buy all the produce out ahead of time to ruin the event; threats of violence by commission men against farmers; and farmers' fear of possible boycotts and lack of business with the commission men if the Market idea did not succeed in the long term.[5]

As the ribbon was cut to open the Market, fifty customers, the ten farmers with produce wagons, a policeman, and various city officials were present. Once the opening ceremony completed, the fifty customers were reported to have pushed past and over the policeman, and began to buy out the first wagon of vegetables before the farmer could even pull the wagon to the curb.[7] One porter, who worked for the Western Avenue wholesalers, apparently grew angry at the direct competition by the farmers, and climbed into one of the produce wagons. He began to freely give away the farmer's goods, before the angry spectators pulled him down. Other farmers complained of their goods being smashed in the street by young men and boys, who were accused of trying to start a riot.[8] In Soul of the City, one farmer was quoted speaking to a reporter describing that first day:

"The next time I come to this place, I'm going to get police protection or put my wagon on stilts. I got rid of everything, all right, but I didn't really sell a turnip. You see, those society women stormed my wagon, crawled over the wheels and crowded me off to respectable distance, say 20 feet (6.1 m). When I got back the wagon was swept as clean as a good housewife's parlor, and there in a bushel basket was a quart of silver."[8]

Hundreds of more customers soon arrived, and before noon that day, all the farmers' produce had sold out.[6]

The Goodwin expansion years

In 1907 Frank Goodwin owned Goodwin Real Estate Company in Seattle, together with his brothers Frank and John. Headquartered in the city's Alaska Building, they owned the Leland Hotel on Pike Street and the undeveloped tracts of land that surrounded Pike Place along the Western Avenue bluff.[9] On the opening day of the Market, Goodwin observed the early morning chaos of farmers dealing with large crowds. Sensing that their land was about to appreciate in value, they began to heavily advertise adjoining plots for sale. Goodwin immediately began to sketch plans for enclosures to house farmers along the company property he owned on Pike Place, and began to develop business plans to lease stalls in those enclosure them to farmers. Funded by Goodwin Real Estate, work began immediately on what is today the Main Arcade of the Pike Place Market, northwest of and adjoining the Leland Hotel.[10]

The first building at the Market, the Main Arcade, opened November 30, 1907.[6] At its opening, a forty-piece band performed for a large cheering crowd.[10] During the early years of the Pike Place Market, Seattle city ordinances limited its hours of operation to only 5 am to 12 noon, Monday through Saturday, and placed initial supervision of the facility with the city Department of Streets and Sewers. Local police gave out vendor stalls to farmers on a first come, first served basis.[11] In 1910, two farmers' associations organized themselves: the Washington Farmers Association represented Japanese farmers; other farmers organized as the White Home Growers Association.[12] By 1911, demand for the Market had grown so much that the number of available stalls had doubled, and extended north from Pike Street to Stewart Street, doubling in size since the opening of the Main Arcade. The west side of the stall lines were soon covered in an overhead canopy and roofing, becoming known as the "dry row". The daily rent for any stall in 1911 was $0.20 a day.[11]

Also in 1911, the City of Seattle created the first full-time jobs to support Market farmers and customers. The Market Inspector, his assistant, and a janitor were the first ever employees of the Pike Place Market. The Inspector, which was renamed Market Master shortly afterward, assigned stalls to farmers and collected their daily fees.[13] The first Market Master, John Winship, initiated a lottery scheme to replace the previous first-come system. To buy a lottery ticket for a stall, farmers had to pay the next day's fee ahead of time. The Pike Place Market had many Japanese farmers, and Winship at first had them choose from a roll of tickets that made it more likely they would receive vendor stalls furthest from the heaviest customer foot traffic. Once the Japanese and other farmers complained about the practice, he quickly stopped it to ensure a fair lottery.[14] In 1912, the Corner Market building was completed, across the street from the Bartell Building, which would later become the Economy Market.[15]

The Market Master and his assistant were also responsible to ensure that farmers used no questionable practices on their customers. Some farmers had weighed down bags of produce for the scales with rocks and gravel, had tried to sneak unripe or spoiled fruit into purchases and, according to one customer, a butcher let his hands "lovingly linger" whenever he weighed meat on his scales. Vendors caught cheating customers would be denied stall rentals for a period of time.[14]

The Public Market & Department Store Company was founded in 1911 by the Goodwins to manage their Pike Place Market properties. They began to design a series of expansions to the Market properties they owned, including the North Arcade, which they planned to build down the bluff along Pike Place. They planned to have all their building expansions set at all times a minimum of ten feet from the sidewalk, to allow extra space for vendors. At the time Frank Goodwin's designs, plans, and intended visual appearance of the Market were considered idiosyncratic.[16]

At the same time as the Goodwins were planning to dramatically expand the Market, the farmers began increasingly to complain about it. They wanted the per-day stall rental fee cut from $0.20 to $0.10, which they were granted. They complained about having to haul produce up the bluff from Western Avenue, and unsuccessfully demanded a mechanical conveyor. Complaints about overcrowding were constant. The farmers also wanted a wooden planked floor set up directly below the Main Arcade for storage. Quickly having grown unhappy with a lack of progress on the part of the city, the farmers used Washington State's then new ballot initiative system to obtain a $150,000 municipal bond issue for their desired improvements.[17]

Seattle Mayor George Cotterill, an engineer, was not in favor of some of the farmer's plans and the idea of such a large municipal bond. Cotterill appointed a committee to study the various requests and complaints of the farmers, and the committee came to the conclusion that the planned floor expansion and conveyor system the farmers wanted would be unsanitary, difficult to maintain, and far more expensive than they had projected. In response, Cotterill drafted an alternate ballot initiative, for a $25,000 municipal bond. Cotterill's initiative would result in Pike Place becoming a paved road rather than the wood road it currently was, would expand the sidewalks along the arcades by 15 feet (4.6 m), and would improve all the Market roadsides for wagon stalls and tables, placing them all under roofing. On March 13, 1913, Seattle voters rejected the farmer initiative, and passed the mayor's initiative. The first major expansion work on the Market began immediately.[17]

In 1914, spurred by the public initiative of the preceding year, the Goodwins implemented the expansion plans they had been preparing for the Market properties they owned. The Main Arcade was expanded downward, along Pike Place's sheer bluff to Western Avenue below, creating five additional lower floors in a massive, "labyrinthine" structure. By the time the expansions were completed, Pike Place Market extended 240 feet (73 m) to the west, past the edge of the bluff. New space was created for several restaurants, bakeries, a creamery, butchers, additional stalls and rows in the lower sections for farmers to sell their goods, grain markets, public toilets, two floors dedicated to storage of meats and produce, 100 retail stores, a theater, and a printing plant. The entire expansion was done modestly, aside from its scale. The basic design elements were steel and wood beams, simple railings of rounded metal, basic wooden banisters, and simple wood and tile floors. Frank Goodwin had wanted always to emphasize the Market's products, rather than its design. There was, at the time. little ornamentation, except for ornate columns at the Pike and Pike Place entrance, and occasional carved reliefs of seafood or produce on the various columns throughout the Market. Goodwin even went so far as to exclude a ceremonial cornerstone from the Market design.[18]

The last of the core buildings of the Market for the coming decades was obtained in 1916 by the Goodwins, when they purchased a long-term lease on the Bartell Building at the corner of 1st Avenue and Pike Street. Renamed to the Economy Market, it became an expansion to the Main Arcade, directly to its southeast. Frank Goodwin redesigned the internal layout of the Bartell Building to include space for an additional 65 vendor stalls, numerous spaces for retail stores, and a full ballroom. Unlike the original designs of the Main Arcade, Frank allowed for more artistic designs to be used on the Economy Market, with frescoes, electric signs, and even more designs used on the columns in the new expansion.[19]

In 1917, with America taking part in World War I, more and more women began to work the various stalls and shops in the Market as their husbands went to war.[20] By the time the war was underway, the Western Avenue commission houses that had led to the creation of the Pike Place Market were in decline, being unable to compete directly with the farmers. The net effect was a near complete stop by the time of World War I of the food price profiteering that had been rampant previously.[20] Washington State government took an interest later in insuring that such things would be prevented during the war for the benefit of its citizens. The Fisheries Commission turned over to the Seattle city government dead hatchery salmon that were killed for eggs and sperm to combat rising fish prices. The city created the municipal-owned City Fish Market at Pike Place Market, cutting the cost of salmon by a third. The city-owned fish vendor business would only last until the end of World War I, when it was stopped.[21] In 1918, wanting to spend more time on his other business ventures, Frank sold his stake in the Pike Place Market to his brother Arthur, who took control of most of the business.[22]

On February 6, 1919, nearly all of Seattle's labor unions took part in a work stoppage. News of this began to spread days earlier in the local newspapers, leading to a panicked run on the goods at the Market. The labor strike affected the delivery of goods to the Market, and lasted five days, during which the Market was nearly deserted. It would become the longest period of inactivity in the history of the Pike Place Market.[23]

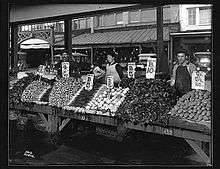

Throughout the early 1920s, business continued to boom at the Pike Place Market. The north side of the Corner Market became the Sanitary Market, housing delicatessens, butchers, restaurants, and bakeries. Three Girls Bakery opened, which would draw large crowds to watch their new automated doughnut machines. The so-called "mosquito fleet", the precursor to the modern Washington State Ferry system, would bring shoppers from various islands in Puget Sound to shop, and Market vendors began to bring goods to the docks for the island residents to buy direct when they saw the ships approach. The ships would only arrive mid-morning, so islanders had no ability to get the best produce at the opening of the Market. Seeing an opportunity, the Hotel Dix, which was located at the time just north of the Market, would offer special overnight rates to island residents that allowed them to stay on the mainland with an early morning wake-up call to compete with local residents for the best goods. To compete for all of these customers, Market vendors began to arrange their goods in elaborate patterns. The Liberty Theater, on First Avenue, hired attendants to watch customer's Market purchases who paid the price of a nickel matinee while they shopped more. The area became a social scene, where young Seattle locals went to see and be seen. Children from an orphanage in Des Moines, Washington performed street concerts on Saturdays.[24]

In September 1920, the Seattle City Council quietly passed an ordinance that farmer's stalls at the Market could no longer be placed in the street, in response to complaints from some local businesses about traffic flow.[25] A public outcry immediately followed from the farmers, merchants, and various citizen's groups. Visiting celebrities even played a role in the public debate, such as a member of New York City's Tiffany family shopping at the Market, gaining the farmers favorable press coverage.[26] In the midst of the turmoil, the Westlake Market Company pushed itself into the situation, proposing that they would build a two-floor underground market at a building they owned on Fifth Avenue, four blocks from the existing Pike Place Market.[25] The Goodwins, in response, proposed another counter-plan to leverage insurance bonds to finance another further expansion of the Market. As the city government began to quickly lean towards the Westlake proposal, the farmers began to formally organize together for the first time to protect their interests. The deciding Seattle City Council vote in April 1921 was in favor of retaining the existing Market location, and the Goodwins immediately began work on their next expansions.[27]

World War II era

At the time of the bombing of Pearl Harbor December 7, 1941, many of the farmers selling in Pike Place Market were Japanese-Americans. The late Seattle historian Walt Crowley estimated that they might have been as many as four-fifths of the farmers selling produce from stalls.[6] President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 February 19, 1942, which eventually forced all Americans of Japanese ancestry in an "exclusion zone" that included the entirety of the West Coast states and southern Arizona into internment camps.[28] On March 11, Executive Order 9095 created the Office of the Alien Property Custodian and gave it discretionary, plenary authority over all alien property interests. Many assets were frozen, creating immediate financial difficulty for the affected aliens, preventing most from moving out of the exclusion zones.[29] Many Japanese Americans were effectively dispossessed.[30]

Plans to destroy the Market

In 1963, a proposal was floated to demolish Pike Place Market and replace it with Pike Plaza, which would include a hotel, an apartment building, four office buildings, a hockey arena, and a parking garage. This was supported by the mayor, many on the city council, and a number of market property owners. However, there was significant community opposition, including help from Betty Bowen, Victor Steinbrueck, and others from the board of Friends of the Market, and an initiative was passed on November 2, 1971 that created a historic preservation zone and returned the Market to public hands. The Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority (PDA) was created by the city to run the Market. Over the course of the 1970s, all the Market's historic buildings were restored and renovated using the original plans and blueprints and appropriate materials.

Battle for ownership of the Market

In the 1980s, federal welfare reform squeezed the social services based in the Market. As a result, a nonprofit group, the Pike Place Market Foundation, was established by the PDA to raise funds and administer the Market's free clinic, senior center, low-income housing, and childcare center. Also in the 1980s the wooden floors on the top arcade were replaced with tiles (so as to prevent water damage to merchandise on the lower floors) that were laid by the PDA after staging a hugely successful capital campaign - people could pay $35 to have their name(s) inscribed on a tile. Between 1985 and 1987, more than 45,000 tiles were installed and nearly 1.6 million dollars was raised.

The 1983 Hildt Amendment or Hildt Agreement (named after Seattle City Council member Michael Hildt) struck a balance between farmers and craftspeople in the daystalls.[31] The agreement set rules that would last for ten years from August 1, 1983, and that would be successively renewable for further terms of five years.[32] The precise formula it laid out stood for over 15 years, and it set the precedent for today's allocation of daystalls, in that it gave craftspeople priority in the North Arcade and farmers priority elsewhere.[31]

Victor Steinbrueck Park

Victor Steinbrueck Park directly north of the market was originally Market Park. From about 1909 the site held an armory, which was damaged by fire in 1962. The land was taken over by the city in 1968, and the remnant of the armory was razed. In 1970 the land passed to park usage. The resulting Market Park was majorly redesigned in 1982. After Steinbrueck's 1985 death, it was renamed after the architect who was instrumental in the market's preservation.[33]

Modern day

In 1998, the PDA decided to end the Hildt Agreement. While their proposed new rule to allocate daystalls was generally seen as more favorable to farmers, there were both farmers and craftspeople who objected, especially because the PDA's timing gave them little chance to study the changes. At their last meeting before the August 1 deadline, the PDA voted 8-4, to notify the City of its intent not to renew the Agreement. The City Council did not accept the proposed substitute. The Council and PDA extended the Hildt agreement 9 months and the council agreed to an extensive public review process in which the Market Constituency played a major role.[34]

The public meetings did not result in a clear consensus, but did provide enough input for city councilmember Nick Licata to draft a revised version of the Hildt Agreement.[34] Adopted in February 1999, it became known as the Licata-Hildt Agreement. The bad blood generated by the conflict spurred an audit of PDA practices by the City Auditor; the audit was critical of the PDA for occasionally violating the "spirit" of its Charter, but exonerated it of any wrongdoing.[35]

Centennial

Pike Place Market celebrated its 100-year anniversary on August 17, 2007. A wide variety of activities and events took place, and a concert was held in Victor Steinbrueck Park in the evening,[36] consisting entirely of songs related one or another way to Seattle. The "house band" for the concert called itself The Iconics, and consisted of Dave Dederer and Andrew McKeag (guitarists of the Presidents of the United States of America or PUSA); Mike Musberger (drummer of The Posies and The Fastbacks); Jeff Fielder (bassist for singer/songwriter Sera Cahoone); and Ty Bailie (keyboard player of Department of Energy). Other performers included Chris Ballew (also of PUSA), Sean Nelson of Harvey Danger, Choklate, Paul Jensen of the Dudley Manlove Quartet, Rachel Flotard of Visqueen, Shawn Smith of Brad, Stone Gossard and Mike McCready of Pearl Jam, John Roderick of the Long Winters, Evan Foster of the Boss Martians, Artis the Spoonman, Ernestine Anderson, and the Total Experience Gospel Choir.[37]

References

- Notes

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 17

- 1 2 "History of the Market", Pike Place Market, archived from the original on September 30, 2007, retrieved December 15, 2005

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, pp. 18–19

- 1 2 Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 20

- 1 2 3 4 Crowley 1999.

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 13

- 1 2 Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 14

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 23

- 1 2 Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 25

- 1 2 Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 28

- ↑ Farmers and the Market, part of a Seattle Municipal Archives series for the Market centennial in 2007. Accessed online 13 October 2008.

- ↑ Jones 1999, p. 12 (p. 24 of the PDF)

- 1 2 Shorett & Morgan 2007, pp. 28–30

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 36

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 32

- 1 2 Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 30

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, pp. 32–33

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 33

- 1 2 Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 41

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, pp. 42–43

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 35

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, pp. 45–46

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, pp. 36–41

- 1 2 Shorett & Morgan 2007, p. 50

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, pp. 50–51

- ↑ Shorett & Morgan 2007, pp. 51–53

- ↑ Chapter 2: Executive Order 9066 in Tetsuden Kashima and the United States Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, University of Washington Press, ISBN 0-295-97558-X. Reproduced online on the site of the National Park Service. Accessed online 14 October 2008.

- ↑ Korematsu v. United States dissent by Justice Owen Josephus Roberts, reproduced at findlaw.com, Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ↑ Brodkin 2001, p. 380.

- 1 2 Mark Worth, Daystalled again, Seattle Weekly, May 27, 1998. Accessed 10 October 2008.

- ↑ Nick Licata, Urban Politics #48, 19 October 1998. Accessed 15 October 2008

- ↑ Victor Steinbrueck Park, Seattle Parks and Recreation. Accessed 15 October 2008.

- 1 2 Jones 1999, p. iv (p. 8 of PDF).

- ↑ Jones 1999, passim, especially iv, 19 (p. 8, 31 of PDF).

- ↑ 100 Years, 100% Seattle, Pike Place Market, 2007. Accessed online 1 February 2008.

- ↑ Pike Place Market, Seattle Channel. Accessed 13 October 2008.

- Bibliography

- Brodkin, Karen (2001), "Diversity in Anthropological Theory", in Susser, Ida; Patterson, Thomas Carl, Cultural Diversity in the United States: A Critical Reader, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 0-631-22213-8.

- Crowley, Walt (1999-07-29), Pike Place Market (Seattle)—Thumbnail History, HistoryLink.org, retrieved 2006-07-21.

- Crowley, Walt (1978), National Trust Guide Seattle, New York: Preservation Press, John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

- Crowley, Walt; Dorpat, Paul (1998), National Trust Guide Seattle, New York: National Trust for Historic Preservation in the United States / John Wiley & Sons, Inc., ISBN 0-471-18044-0.

- Elenga, Maureen R. (2007), Seattle Architecture, Seattle: Seattle Architecture Foundation, ISBN 978-0-615-14129-9.

- Evans, Jack R. (1991), Little History of Pike Place Market, Seattle: SCW Publications, ISBN 1-877882-04-6.

- Flom, Eric L. (2002-06-20), Moore Theatre (Seattle), HistoryLink.org, retrieved 2006-07-21.

- Jones, David G. (1999-12-08), Management Review of the Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority (PDF), Office of the City Auditor, retrieved 2008-10-07. Jones was Deputy City Auditor at the time of publication.

- Lange, Greg (1 January 1999, lead paragraph updated 2006), Seattle's Pike Place Market opens on August 17, 1907, HistoryLink.org, retrieved 2006-07-21 Check date values in:

|date=(help). - Lehmann, Thelma (2001-10-25), Masters of Northwest Art: Mark Tobey—Guru of Seattle Painters, HistoryLink, retrieved 2006-04-21. Rewrite of work originally published in Hans and Thelma Lehmann, Out of the Cultural Dustbin: Sentimental Musings on the Arts & Music in Seattle from 1936 to 1992 (Seattle: Lehmann, 1992), 73-75.

- Long, Priscilla (2002-07-17), Mark Tobey paints the first of his influential white-writing style paintings in November or December 1935., HistoryLink, retrieved 2006-04-21

- McRoberts, Patrick (2000-03-16), Seattle Aquarium, HistoryLink, retrieved 2006-04-21

- NRHP (2006), WASHINGTON - King County, National Register of Historic Places, retrieved 2006-07-21. Link is to first of 5 pages. "Alaska Trade Building" (added 1971) and "Butterworth Building" (added 1971) are on p. 1 of 5. "Guiry and Schillestad Building" (added 1985) is on p. 2 of 5. "Moore Theatre and Hotel" (added 1974) and "New Washington Hotel" (added 1989) are on p. 3 of 5.

- Phelps, Myra L. (1978), Public works in Seattle, Seattle: Seattle Engineering Department, ISBN 0-9601928-1-6.

- Pike Place Market (2008-03-25), Daystall Rules and Regulations (PDF), Pike Place Market, retrieved 2008-10-09.

- Shenk, Carol; Pollack, Laurie; Dornfeld, Ernie; Frantilla, Anne; Neman, Chris (2002-06-26, maps .jpg c. 2002-06-15), "About neighborhood maps", Seattle City Clerk's Office Neighborhood Map Atlas, Office of the Seattle City Clerk, Information Services, retrieved 2006-04-21 Check date values in:

|date=(help). Shenk et al. provide a substantial bibliography with extensive primary sources. - Seattle City Clerk (2006-04-30), "About the Seattle City Clerk's On-line Information Services", Information Services, Seattle City Clerk's Office, retrieved 2006-05-21. See heading, "Note about limitations of these data".

- Seattle Parks and Recreation (September 2006), "Chapter 3 – Affected Environment, Environmental Impacts, and Mitigation Measures" (PDF), Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the Central Waterfront Master Parks Plan, Seattle: Department of Parks and Recreation, retrieved 2008-10-15

- Speidel, William C. (1967), Sons of the profits; or, There's no business like grow business: the Seattle story, 1851-1901, Seattle: Nettle Creek Publishing Company, ISBN 0-914890-00-X. Also ISBN 0-914890-06-9. Speidel provides a substantial bibliography with extensive primary sources.

- Wilma, David (1999-06-27), Voters preserve Seattle's historic Pike Place Market on November 2, 1971., HistoryLink, retrieved 2006-04-21

- Shorett, Alice; Morgan, Murray (2007-08-30), Soul of the City: The Pike Place Public Market, University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98746-0

- Thomas Street History Services (November 2006), Context Statement: The Central Waterfront (PDF), Seattle: The Historic Preservation Program, Department of Neighborhoods, City of Seattle, retrieved 2008-10-29

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pike Place Market. |

- Official site

- Pike Place Market Centennial, Seattle Municipal Archives

- Pike Place Market, Seattle Channel. Over 50 videos pertaining to Pike Place Market, ranging from history to musical performances.

- Market Ghost Tours

- Movies that filmed at Pike Place Market, MoviePlaces.tv

- Virtual Tour inside market

- Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority

- Guide to the Department of Community Development's Pike Place Market Records 1894-1990, Washington State University.

- Guide to the Pike Place Market Visual Images Collection 1894-1984, Washington State University.

- Guide to the Pike Place Market Historical District Records 1971-1989, Washington State University.

- Pike Place Market media images, University of Washington Library.