History of the Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles is a royal château in Versailles in the Île-de-France region of France. When the château was built, Versailles was a country village; today, however, it is a suburb of Paris, some 20 kilometres southwest of the French capital. The court of Versailles was the centre of political power in France from 1682, when Louis XIV moved from Paris, until the royal family was forced to return to the capital in October 1789 after the beginning of the French Revolution. Versailles is therefore famous not only as a building, but as a symbol of the system of absolute monarchy of the Ancien Régime.

Origins

The earliest mention of the name of Versailles is found in a document which predates 1038, the Charte de l'abbaye Saint-Père de Chartres (Charter of the Saint-Père de Chartres Abbey),[1] in which one of the signatories was a certain Hugo de Versailliis (Hugues de Versailles), who was seigneur of Versailles.[2]

During this period, the village of Versailles centred on a small castle and church and the area was governed by a local lord. Its location on the road from Paris to Dreux and Normandy brought some prosperity to the village but, following an outbreak of the Plague and the Hundred Years' War, the village was largely destroyed and its population sharply declined.[3] In 1575, Albert de Gondi, a naturalized Florentine who gained prominence at the court of Henry II, purchased the seigneury of Versailles.

Ancien Régime

Louis XIII

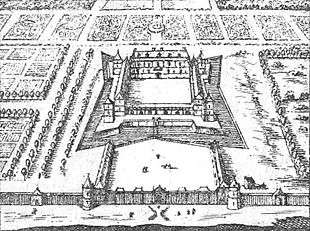

In the early seventeenth century, Gondi invited Louis XIII on several hunting trips in the forests surrounding Versailles. Pleased with the location, Louis ordered the construction of a hunting lodge in 1624. Designed by Philibert Le Roy, the structure, a small château, was constructed of stone and red brick with a based roof. Eight years later, Louis obtained the seigneury of Versailles from the Gondi family and began to make enlargements to the château.[5]

A vignette of Versailles from the 1652 Paris map of Jacques Gomboust shows a traditional design: an entrance court with a corps de logis on the far western end, flanked by secondary wings on the north and south sides, and closed off by an entrance screen. Adjacent exterior towers were located at the four corners with the entire structure surrounded by a moat. This was preceded by two service wings, creating a forecourt with a grilled entrance marked by two round towers. The vignette also shows a garden on the western side of the château with a fountain on the central axis and rectangular planted parterres to either side.[6]

Louis XIV had played and hunted at the site as a boy.[7] With a few modifications, this structure would become the core of the new palace.[8]

Louis XIV

Louis XIII's successor, Louis XIV, had a great interest in Versailles. He settled on the royal hunting lodge at Versailles and over the following decades had it expanded into one of the largest palaces in the world.[9] Beginning in 1661, the architect Louis Le Vau, landscape architect André Le Nôtre, and painter-decorator Charles Lebrun began a detailed renovation and expansion of the château. This was done to fulfill Louis XIV's desire to establish a new centre for the royal court. Following the Treaties of Nijmegen in 1678, he began to gradually move the court to Versailles. The court was officially established there on 6 May 1682.[10]

By moving his court and government to Versailles, Louis XIV hoped to extract more control of the government from the nobility, and to distance himself from the population of Paris. All the power of France emanated from this centre: there were government offices here, as well as the homes of thousands of courtiers, their retinues, and all the attendant functionaries of court.[11] By requiring that nobles of a certain rank and position spend time each year at Versailles, Louis prevented them from developing their own regional power at the expense of his own and kept them from countering his efforts to centralise the French government in an absolute monarchy.[12] The meticulous and strict court etiquette that Louis established, which overwhelmed his heirs with its petty boredom, was epitomised in the elaborate ceremonies and exacting procedures that accompanied his rising in the morning, known as the Lever, divided into a petit lever for the most important and a grand lever for the whole court. Like other French court manners, étiquette was quickly imitated in other European courts.[13]

The expansion of the château became synonymous with the absolutism of Louis XIV.[14] In 1661, following the death of Cardinal Mazarin, chief minister of the government, Louis had declared that he would be his own chief minister. The idea of establishing the court at Versailles was conceived to ensure that all of his advisors and provincial rulers would be kept close to him. He feared that they would rise up against him and start a revolt. He thought that if he kept all of his potential threats near him, they would be powerless. After the disgrace of Nicolas Fouquet in 1661 – Louis claimed the finance minister would not have been able to build his grand château at Vaux-le-Vicomte without having embezzled from the crown – Louis, after the confiscation of Fouquet’s state, employed the talents of Le Vau, Le Nôtre, and Le Brun, who all had worked on Vaux-le-Vicomte, for his building campaigns at Versailles and elsewhere. For Versailles, there were four distinct building campaigns (after minor alterations and enlargements had been executed on the château and the gardens in 1662–1663), all of which corresponded to Louis XIV’s wars.[15]

First building campaign

The first building campaign (1664–1668) commenced with the Plaisirs de l’Île enchantée of 1664, a fête that was held between 7 and 13 May 1664. The fête was ostensibly given to celebrate the two queens of France – Anne of Austria, the Queen Mother, and Marie-Thérèse, Louis XIV’s wife – but in reality honored the king’s mistress, Louise de La Vallière. The celebration of the Plaisirs de l’Île enchantée is often regarded as a prelude to the War of Devolution, which Louis waged against Spain. The first building campaign (1664–1668) involved alterations in the château and gardens to accommodate the 600 guests invited to the party.[16]

Second building campaign

.jpg)

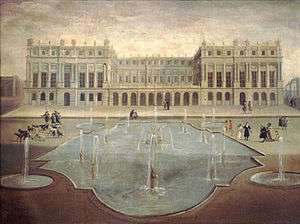

The second building campaign (1669–1672) was inaugurated with the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ended the War of Devolution. During this campaign, the château began to assume some of the appearance that it has today. The most important modification of the château was Le Vau’s envelope of Louis XIII’s hunting lodge. The enveloppe – often referred to as the château neuf to distinguish it from the older structure of Louis XIII – enclosed the hunting lodge on the north, west, and south. The new structure provided new lodgings for the king and members of his family. The main floor – the piano nobile – of the château neuf was given over entirely to two apartments: one for the king, and one for the queen. The grand appartement du roi occupied the northern part of the château neuf and grand appartement de la reine occupied the southern part.

.jpg)

The western part of the enveloppe was given over almost entirely to a terrace, which was later enclosed with the construction of the Hall of Mirrors (Galerie des Glaces). The ground floor of the northern part of the château neuf was occupied by the appartement des bains, which included a sunken octagonal tub with hot and cold running water. The king’s brother and sister-in-law, the duke and duchesse d’Orléans occupied apartments on the ground floor of the southern part of the château neuf. The upper story of the château neuf was reserved for private rooms for the king to the north and rooms for the king’s children above the queen’s apartment to the south.[18]

Significant to the design and construction of the grands appartements is that the rooms of both apartments are of the same configuration and dimensions – a hitherto unprecedented feature in French palace design. It has been suggested that this parallel configuration was intentional as Louis XIV had intended to establish Marie-Thérèse d’Autriche as queen of Spain, and thus thereby establish a dual monarchy.[19] Louis XIV’s rationale for the joining of the two kingdoms was seen largely as recompense for Philip IV's failure to pay his daughter Marie-Thérèse’s dowry, which was among the terms of capitulation to which Spain agreed with the promulgation of the Treaty of the Pyrenees, which ended the war between France and Spain that began in 1635 during the Thirty Years’ War. Louis XIV regarded his father-in-law’s act as a breach of the treaty and consequently engaged in the War of Devolution.

Both the grand appartement du roi and the grand appartement de la reine formed a suite of seven enfilade rooms. Each room is dedicated to one of the then known celestial bodies and is personified by the appropriate Greco-Roman deity. The decoration of the rooms, which was conducted under Le Brun's direction depicted the “heroic actions of the king” and were represented in allegorical form by the actions of historical figures from the antique past (Alexander the Great, Augustus, Cyrus, etc.).[20]

Third building campaign

With the signing of the Treaty of Nijmegen in 1678, which ended the Dutch War, the third building campaign at Versailles began (1678–1684). Under the direction of the architect, Jules Hardouin-Mansart, the Palace of Versailles acquired much of the look that it has today. In addition to the Hall of Mirrors, Hardouin-Mansart designed the north and south wings, which were used, respectively, by the nobility and Princes of the Blood, and the Orangerie. Le Brun was occupied not only with the interior decoration of the new additions of the palace, but also collaborated with Le Nôtre's in landscaping the palace gardens.[21] As symbol of France’s new prominence as a European super-power, Louis XIV officially installed his court at Versailles in May 1682.[14]

Fourth building campaign

Soon after the crushing defeat of the War of the League of Augsburg (1688–1697) and owing possibly to the pious influence of Madame de Maintenon, Louis XIV undertook his last building campaign at Versailles. The fourth building campaign (1699–1710) concentrated almost exclusively on construction of the royal chapel designed by Hardouin-Mansart and finished by Robert de Cotte and his team of decorative designers. There were also some modifications in the appartement du roi, namely the construction of the Salon de l’Œil de Bœuf and the King’s Bedchamber. With the completion of the chapel in 1710, virtually all construction at Versailles ceased; building would not be resumed at Versailles until some twenty one years later during the reign of Louis XV.[22]

|

|

|

| The palace in 1668 | The palace in 1674 | The palace in 1680 |

Louis XV

After the death of the Louis XIV in 1715, the five-year-old king Louis XV, the court, and the Régence government of Philippe d’Orléans returned to Paris. In May 1717, during his visit to France, the Russian czar Peter the Great stayed at the Grand Trianon. His time at Versailles was used to observe and study the palace and gardens, which he later used as a source of inspiration when he built Peterhof on the Bay of Finland west of Saint Petersburg.[23]

During the reign of Louis XV, Versailles underwent transformation, but not on the scale that had been seen during the reign of Louis XIV. When the king and the court returned to Versailles in 1722, the first project was the completion of the Salon d'Hercule, which had been begun during the last years of Louis XIV's reign but was never finished due to the king’s death.[24]

Significant among Louis XV’s contributions to Versailles were the petit appartement du roi; the appartements de Mesdames, the appartement du dauphin, and the appartement de la dauphine on the ground floor; and the two private apartments of Louis XV – petit appartement du roi au deuxième étage (later transformed into the appartement de Madame du Barry) and the petit appartement du roi au troisième étage – on the second and third floors of the palace. The crowning achievements of Louis XV’s reign were the construction of the Opéra and the Petit Trianon.[25]

Equally significant was the destruction of the Escalier des Ambassadeurs (Ambassadors' Stair), the only fitting approach to the State Apartments, which Louis XV undertook to make way for apartments for his daughters.[26]

The gardens remained largely unchanged from the time of Louis XIV; only the completion of the Bassin de Neptune between 1738 and 1741 was the most important legacy Louis XV made to the gardens.[27] Towards the end of his reign, Louis XV, under the advice of Ange-Jacques Gabriel, began to remodel the courtyard façades of the palace. With the objective revetting the entrance of the palace with classical façades, Louis XV began a project that was continued during the reign of Louis XVI, but which did not see completion until the 20th century.[28]

Louis XVI

In 1774, shortly after his ascension, Louis XVI ordered an extensive replanting of the bosquets of the gardens, since many of the century-old trees had died. Only a few changes to Le Nôtre's design were made: some bosquets were removed, others altered, including the Bains d'Apollon (north of the Parterre de Latone), which was redone after a design by Hubert Robert in anglo-chinois style (popular during the late 18th century), and the Labyrinthe (at the southern edge of the garden) was converted to the small Jardin de la Reine.[29] In the interior of the palace, the library and the salon des jeux in the petit appartement du roi and the petit appartement de la reine, redecorated by Richard Mique for Marie-Antoinette, are among the finest examples of the style Louis XVI.[30]

French Revolution

On 6 October 1789, the royal family had to leave Versailles and move to the Tuileries Palace in Paris, as a result of the Women's March on Versailles.[31] During the early years of the French Revolution, preservation of the palace was largely in the hands of the citizens of Versailles. In October 1790, Louis XVI ordered the palace to be emptied of its furniture, requesting that most be sent to the Tuileries Palace. In response to the order, the mayor of Versailles and the municipal council met to draft a letter to Louis XVI in which they stated that if the furniture was removed, it would certainly precipitate economic ruin on the city.[32] A deputation from Versailles met with the king on 12 October after which Louis XVI, touched by the sentiments of the residents of Versailles, rescinded the order.

Eight months later, however, the fate of Versailles was sealed: on 21 June 1791, Louis XVI was arrested at Varennes after which the Assemblée nationale constituante accordingly declared that all possessions of the royal family had been abandoned. To safeguard the palace, the Assemblée nationale constituante ordered the palace of Versailles to be sealed. On 20 October 1792 a letter was read before the National Convention in which Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière, interior minister, proposed that the furnishings of the palace and those of the residences in Versailles that had been abandoned be sold and that the palace be either sold or rented. The sale of furniture transpired at auctions held between 23 August 1793 and 30 nivôse an III (19 January 1795). Only items of particular artistic or intellectual merit were exempt from the sale. These items were consigned to be part of the collection of a museum, which had been planned at the time of the sale of the palace furnishings.

In 1793, Charles-François Delacroix deputy to the Convention and father of the painter Eugène Delacroix proposed that the metal statuary in the gardens of Versailles be confiscated and sent to the foundry to be made into cannon.[33] The proposal was debated but eventually it was tabled. On 28 floréal an II (5 May 1794) the Convention decreed that the château and gardens of Versailles, as well as other former royal residences in the environs, would not be sold but placed under the care of the Republic for the public good.[34] Following this decree, the château became a repository for art work seized from churches and princely homes. As a result of Versailles serving as a repository for confiscated art works, collections were amassed that eventually became part of the proposed museum.[35]

Among the items found at Versailles at this time a collection of natural curiosities that has been assembled by the sieur Fayolle during his voyages in America. The collection was sold to the comte d’Artois and was later confiscated by the state. Fayolle, who had been nominated to the Commission des arts, became guardian of the collection and was later, in June 1794, nominated by the Convention to be the first directeur du Conservatoire du Muséum national de Versailles.[36] The next year, André Dumont the people's representative, became administrator for the department of the Seine-et-Oise. Upon assuming his administrative duties, Dumont was struck with the deplorable state into which the palace and gardens had sunk. He quickly assumed administrative duties of the château and assembled a team of conservators to oversee the various collections of the museum.[37]

One of Dumont’s first appointments was that of Huges Lagarde (10 messidor an III (28 June 1795), a wealthy soap merchant from Marseille with strong political connections, as bibliographer of the museum. With the abandonment of the palace, there remained no less than 104 libraries which contained in excess of 200,000 printed volumes and manuscripts. Lagarde, with his political connections and his association with Dumont, became the driving force behind Versailles as a museum at this time. Lagarde was able to assemble a team of curators including sieur Fayolle for natural history and, Louis Jean-Jacques Durameau, the painter responsible for the ceiling painting in the Opéra, was appointed as curator for painting.[38]

Owing largely to political vicissitudes that occurred in France during the 1790s, Versailles succumbed to further degradations. Mirrors were assigned by the finance ministry for payment of debts of the Republic and draperies, upholstery, and fringes were confiscated and sent to the mint to recoup the gold and silver used in their manufacture. Despite its designation as a museum, Versailles served as an annex to the Hôtel des Invalides pursuant to the decree of 7 frimaire an VIII (28 November 1799), which commandeered part of the palace and which had wounded soldiers being housed in the petit appartement du roi.[39]

In 1797, the Muséum national was reorganised and renamed Musée spécial de l’École française.[40] The grands appartements were used as galleries in which the morceaux de réception submitted by artists seeking admission to the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture during the 17th and 18th centuries, the series The Life of Saint Bruno by Eustache Le Sueur and the Life of Marie de Médicis by Peter Paul Rubens were placed on display. The museum, which included the sculptures in the garden, became the finest museum of classic French art that had existed.[41]

First Empire

With the advent of Napoléon and the First Empire, the status of Versailles changed. Paintings and art work that had previously been assigned to Muséum national and the Musée spécial de l’École française were systematically dispersed to other locations and eventually the museum was closed. In accordance to provisions of the 1804 Constitution, Versailles was designated as an imperial palace for the department of the Seine-et-Oise.[42]

While Napoléon did not reside in the château, apartments were, however, arranged and decorated for the use of the empress Marie-Louise. The emperor chose to reside at the Grand Trianon. The château continued to serve, however, as an annex of the Hôtel des Invalides[43] Nevertheless, on 3 January 1805, Pope Pius VII, who came to France to officiate at Napoléon's coronation, visited the palace and blessed the throng of people gathered on the parterre d'eau from the balcony of the Hall of Mirrors.[44]

Bourbon Restoration

The Bourbon Restoration saw little activity at Versailles. Areas of the gardens were replanted but no significant restoration and modifications of the interiors were undertaken, despite the fact that Louis XVIII would often visit the palace and walk through the vacant rooms.[45] Charles X chose the Tuileries Palace over Versailles and rarely visited his former home.[46]

July Monarchy

With the Revolution of 1830 and the establishment of the July Monarchy, the status of Versailles changed. In March 1832, the Loi de la Liste civile was promulgated, which designated Versailles as a crown dependency. Like Napoléon before him, Louis-Philippe chose to live at the Grand Trianon; however, unlike Napoléon, Louis-Philippe did have a grand design for Versailles.

In 1833, Louis-Philippe proposed the establishment of a museum dedicated to “all the glories of France,” which included the Orléans dynasty and the Revolution of 1830 that put Louis-Philippe on the throne of France. For the next decade, under the direction of Frédéric Nepveu and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine, the château underwent irreversible alterations.[47] The museum was officially inaugurated on 10 June 1837 as part of the festivities that surrounded the marriage of the Prince royal, Ferdinand-Philippe d’Orléans with princess Hélène of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and represented one of the most ambitious and costly undertakings of Louis-Philippe’s reign. Over, the emperor at the king’s home – Napoléon at Louis XIV’s; in a word, it is having given to this magnificent book that is called French history this magnificent binding that is called Versailles (Victor Hugo).[48]

Later, Balzac characterised the effort in less laudatory terms as the “hospital of the glories of France”.[49]

The southern wing (Aile du Midi) was given over to the Galerie des Batailles (Hall of Battles), which necessitated the demolition of most of the apartments of the Princes of the Blood who lived in this part of the palace during the Ancien Régime. The Galerie des Batailles was modeled on the Grande Galerie of the Louvre Palace and was intended to glorify French military history from the Battle of Tolbiac (traditionally dated 495) to the Battle of Wagram (5–6 July 1809). While a number of the paintings were of questionable quality, a few were masterpieces, such as the Battle of Taillebourg by Eugène Delacroix. Part of the northern wing (Aile du Nord) was converted to the Salle des Croisades, a room dedicated to famous knights of the Crusades and decorated with their names and coats of arms. The apartments of the dauphin and the dauphine as well as those of Louis XV’s daughters on the ground floor of the corps de logis were transformed into portrait galleries. To accommodate the displays, some of the boiseries were removed and either put into storage or sold. During the Prussian occupation of the palace in 1871, the boiseries in storage were burned as firewood.[50]

Second Empire

During the Second Empire, the museum remained essentially intact. The palace did serve as the backdrop for a number of state events including the visit by Queen Victoria.

Versailles under Pierre de Nolhac

Pierre de Nolhac arrived at the Palace of Versailles in 1887 and was appointed curator of the museum 18 November 1892.[51] Upon his arrival, he planned to re-introduce historical galleries, organized scientifically, in contrast to the approach of Louis-Philippe, who had created the first galleries in a manner aimed at glorifying the history of France. At the same time, Nolhac began to restore the palace to its appearance before the Revolution. To achieve these two goals, Nolhac removed rooms, took down the artworks and gave the rooms some historical scenery. He explained in his memoirs, for example that "the first room sacrificed was that of the kings of France which had walls lined with effigies, real and imaginary, of our kings since Clovis".[52] The revolution wrought by Nolhac produced a new awareness of the castle. Members of high society and nobility, such as the Duke of Aumale and the Empress Eugenie flocked to see new developments. Nolhac also working to bring in foreign personalities. On 8 October 1896, Czar Nicolas II and his wife Alexandra, arrived at Versailles. Nolhac also organized events aimed at raising the awareness of potential donors to the palace. The owner of the New York Herald, Gordon Bennett, gave 25,000 francs for restructuring the 18th-century rooms. The development of private donations led to the creation of the Friends of Versailles in June 1907.

The Van der Kemp period

Under the aegis of Gérald Van der Kemp, chief conservator of the museum from 1952 to 1980, the palace witnessed some of its most ambitious conservation and restoration projects: the Opéra (completed in 1957); the Grand Trianon (1965); the Chambre de la Reine (1975); the Chambre de Louis XIV and the Hall of Mirrors (1980).[53] At this time, the ground floor of the northern wing was converted into a gallery of French history from the 17th century to the 19th century. Additionally, at this time, policy was established in which the French government would aggressively seek to acquire as much of original furniture and artwork that had been dispersed at the time of the Revolution of 1789 as possible.[54]

Contemporary Versailles

With the past and ongoing restoration and conservation projects at Versailles, the Fifth Republic has enthusiastically promoted the museum as one of France’s foremost tourist attractions.[55] The palace, however, still serves political functions. Heads of state are regaled in the Hall of Mirrors; the Sénat and the Assemblée Nationale meet in congress in Versailles to revise or otherwise amend the French Constitution, a tradition that came into effect with the promulgation of the 1875 Constitution.[56] The Public Establishment of the Palace, Museum and National Estate of Versailles was created in 1995.

Château de Versailles Spectacles organised the Jeff Koons Versailles exhibition, held from 9 October 2008 to 4 January 2009. Jeff Koons said that "I hope the juxtaposition of today's surfaces, represented by my work, with the architecture and fine arts of Versailles will be an exciting interaction for the viewer."[57] Elena Geuna and Laurent Le Bon, curators of the exhibition present it as follow: "It is the city aspect that underlies this entire venture. In recent years, many a cultural institution has attempted a confrontation between a heritage setting and contemporary works. The originality of this exhibition seems to us somewhat different, as regards both the chosen venue and the way it has been laid out. Echo, dialectic, opposition, counterpoint... Not for us to judge!"[57]

Notes

- ↑ Guérard 1840, p. 125.

- ↑ Guérard 1840, p. xiv.

- ↑ Bluche, 1990; Thompson, 2006; Verlet, 1985.

- ↑ Garrigues 2001, p. 37.

- ↑ Batiffol, 1913; Bluche, 1991; Marie, 1968; Nolhac, 1901; Verlet, 1985

- ↑ Hazlehurst 1980, p. 60.

- ↑ Versailles, The Dream of a King, directed by Paul Burgess, BBC TV

- ↑

- ↑ Félibien, 1703; Marie, 1972; Verlet, 1985.

- ↑ Berger 2008, p. 27.

- ↑ Solnon, 1987.

- ↑ Bluche, 1986, 1991; Bendix, 1978; Solnon, 1987.

- ↑ Benichou, 1948; Bluche, 1991; Solnon 1987.

- 1 2 Bluche, 1986, 1991.

- ↑ Bluche, 1986, 1991; Verlet, 1985.

- ↑ Nolhac, 1899, 1901; Marie, 1968; Verlet, 1985.

- ↑ Berger 1985b, fig. 12 (plan), pp. 41–42; Verlet|1985, p. 74 (fig. 7).

- ↑ Nolhac, 1901; Marie, 1972; Verlet, 1985.

- ↑ Johnson, 1981.

- ↑ Berger, 1985b, pp. 41–50 (Chapter 5: "The Planetary Rooms"); Félibien, 1674; Verlet, 1985.

- ↑ Berger, 1985a; Thompson, 2006; Verlet, 1985.

- ↑ Nolhac 1911; Marie 1976, 1984; Verlet, 1985.

- ↑ Verlet 1985, p. 301.

- ↑ Verlet 1985, pp. 321–324.

- ↑ Verlet, 198, pp. 375–384 (Opéra) and 500–505 (Petit Trianon).

- ↑ Verlet 1985, pp. 307–308.

- ↑ Marie 1984; Thompson, 2006; Verlet 1985, pp. 329–330.

- ↑ Ayers 2004, pp. 340–341..

- ↑ Hoog 1996, p. 372; Verlet 1985, pp. 540–545.

- ↑ Verlet, 1945; Verlet 1985; Ayers 2004, p. 341.

- ↑ Nagel 2009.

- ↑ Gatin 1908. With the withdrawal of the king and the court from Versailles, many of those who had been employed either through a member of the royal family or by the court, followed the court and king to Paris. As a result, the population of Versailles fell from 80,000 to less than 25,000 in the weeks that followed 6 October 1789 (Mauguin, 1934).

- ↑ Gatin 1908, p. ?.

- ↑ Fromageot 1903, p. ?.

- ↑ Fromageot 1903, p. ??.

- ↑ Fromageot 1903, p. ???.

- ↑ Fromageot 1903, p. ????.

- ↑ Fromageot 1903, p. ?????.

- ↑ Gatin 1908, p. ??.

- ↑ Dutilleux 1887, p. ?.

- ↑ Verlet 1985, pp. 661–664.

- ↑ Article 16 : L'Empereur visite les départements : en conséquence, des palais impériaux sont établis aux quatre points principaux de l'Empire. – Ces palais sont désignés et leurs dépendances déterminées par une loi. Source: Constitution of 1804

- ↑ Mauguin, 1940–1942; Pradel, 1937; Verlet, 1985.

- ↑ Mauguin, 1940–1942.

- ↑ Mansel 1999; Thompson 2006.

- ↑ Castelot 1989.

- ↑ Constans 1985; Constans 1998, pp. 246–258; Mauguin, 1937; Verlet, 1985, pp. 661–664.

- ↑ Hugo 1972. “Ce que le roi Louis-Philippe a fait à Versailles est bien. Avoir accompli cette œuvre, c'est avoir été grand comme roi et impartial comme philosophe ; c'est avoir fait un monument national d'un monument monarchique ; c'est avoir mis une idée immense dans un immense édifice ; c'est avoir installé le présent dans le passé, 1789 vis-à-vis de 1688, l'empereur chez le roi, Napoléon chez Louis XIV ; en un mot, c'est avoir donné à ce livre magnifique qu'on appelle l'histoire de France cette magnifique reliure qu'on appelle Versailles.”

- ↑ Balzac 1853.

- ↑ Constans, 1985; 1987; Mauguin, 1937; Verlet,1985.

- ↑ Da Vinha & Masson 2011, p. 261.

- ↑ Da Vinha & Masson 2011, p. 229.

- ↑ Pérouse de Montclos 1991, pp. 10, 284; Lemoine 1976.

- ↑ Kemp 1976; Meyer 1985.

- ↑ Opperman 2004.

- ↑ Article 9: Le siège du pouvoir exécutif et des deux chambres est à Versailles. Source: Constitution of 1875

- 1 2 Jeff Koons Versailles website

Bibliography

- Ayers, Andrew (2004). The Architecture of Paris. Stuttgart; London: Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 9783930698967.

- Balzac, Honoré de (1853). La comédie humaine, vol. 12. Paris: Pilet.

- Batiffol, Louis (1913). "Le château de Versailles de Louis XIII et son architecte Philibert le Roy" Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 4th edition, vol. 10 (November 1913), pp. 341–371 (at Gallica).

- Benichou, Paul (1948). Morales du grand siècle. Paris: Éditions Gallimard. OCLC 259119.

- Berger, Robert W. (1985a). In the Garden of the Sun King: Studies on the Park of Versailles Under Louis XIV. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library. ISBN 9780884021414.

- Berger, Robert W. (1985b). Versailles: The Château of Louis XIV. University Park: The College Arts Association. ISBN 9780271004129.

- Berger, Robert W. (2008). Diplomatic Tours in the Gardens of Versailles Under Louis XIV. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812241075.

- Bendix, Reinhard (1986). Kings or People: Power and the Mandate to Rule. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520023024.

- Bluche, François (1986). Louis XIV. Paris: Arthème Fayard. ISBN 9782213015682.

- Bluche, François (1990). Dictionnaire du Grand Siècle. Paris: Arthème Fayard. ISBN 9782213024257.

- Castelot, André (1988). Charles X: La fin d'un monde. Paris: Perrin. ISBN 9782262005450.

- Constans, Claire (1985). "1837: L'inauguration par Louis-Philippe du musée dédié 'À Toutes les gloires de la France", Colloque Versailles. OCLC 12904910, 761465041.

- Constans, Claire (1987) . "Encadrement et muséographie: l'example du Versailles de Louis-Philippe", Revue de l'Art, vol. 76, pp. 53–56. doi:10.3406/rvart.1987.347630.

- Constans, Claire (1998). Versailles: Absolutism and Harmony. New York: The Vendome Press. ISBN 9782702811252.

- Da Vinha, Mathieu; Masson, Raphaël (2011). Versailles pour les nuls. Paris: Editions Générales First. ISBN 9782754015523.

- Dutilleux, Adolphe (1887). Notice sur le Museum national et le musée spécial de l'École française à Versailles (1792–1823). Versailles: Impr. de Cerf et fils. OCLC 457476198.

- Félibien, Jean-François (1703). Description sommaire de Versailles ancienne et nouvelle. Paris: A. Chrétien. Copy at INHA.

- Fromageot, Paul-Henri (1903). "Le Château de Versailles en 1795, d'après le journal de Hugues Lagarde", Revue de l'histoire de Versailles, pp. 224–240 (at the Internet Archive).

- Garrigues, Dominique (2001). Jardins et jardiniers de Versailles au grand siècle. Seyssel: Champ Vallon. ISBN 9782876733374.

- Gatin, L.-A. (1908). "Versailles pendant la Révolution", Revue de l'histoire de Versailles, pp. 226–253 and 333–352 at the Internet Archive.

- Guérard, Benjamin (1840). Collection des cartulaires de France. Tome I: Cartulaire de l'abbaye de Saint-Père de Chartres. Paris: Crapelet. Copy at Google Books.

- Hazlehurst, F. Hamilton (1980). Gardens of Illusion: The Genius of André Le Nostre. Nashville, Tennessee: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 9780826512093.

- Hoog, Simone (1996). "Versailles", vol. 32, pp. 369–374, in The Dictionary of Art, edited by Jane Turner. New York: Grove. ISBN 9781884446009. Also at Oxford Art Online (subscription required).

- Hugo, Victor (1972). Choses vues, 1830–1846, edited by Hubert Juin. Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 9782070360116.

- Johnson, Kevin Olin (1981). "Il n'y plus de Pyrénées: Iconography of the first Versailles of Louis XIV", Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 6th edition, vol. 97 (January), pp. 29–40.

- Lemoine, Pierre (1976). "La chambre de la Reine", La Revue du Louvre et des musées de France, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 139–145. ISSN 0035-2608.

- Mansel, Philip (1999). Louis XVIII (revised, in English). Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 9780750922173 (paperback).

- Marie, Alfred (1968). Naissance de Versailles. Paris: Édition Vincent, Freal & Cie. OCLC 3731196.

- Marie, Alfred; Marie, Jeanne (1972). Mansart à Versailles. Paris: Editions Jacques Freal. OCLC 746666.

- Marie, Alfred; Marie, Jeanne (1976). Versailles au temps de Louis XIV. Paris: Imprimérie Nationale. OCLC 311957302.

- Marie, Alfred; Marie, Jeanne (1984). Versailles au temps de Louis XV. Paris: Imprimérie Nationale. ISBN 9782110808004.

- Mauguin, Georges (1937). "L'Inauguration du Musée de Versailles", Revue de l'histoire de Versailles (July 1937), pp. 112–146 (at Gallica).

- Mauguin, Georges (1940–1942). "La visite du Pape Pie VII à Versailles le 3 janvier 1805", Revue de l'histoire de Versailles (July 1940 – December 1942), pp. 134–146 (at Gallica).

- Meyer, Daniel (1985). "Un achat manqué par le musée de Versailles en 1852", Colloque Versailles. OCLC 12904910, 761465041.

- Nagel, Susan (2009.) Marie-Therese: The Fate of Marie Antoinette's Daughter. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780747581598.

- Nolhac, Pierre de (1898). Le Chateau de Versailles sous Louis Quinze. Paris: H. Champion. OCLC 894269761. Copy at HathiTrust.

- Nolhac, Pierre de (1899). "La construction de Versailles de Le Vau", Revue de l'Histoire de Versailles, pp. 161–171 (at Gallica).

- Nolhac, Pierre de (1901). La création de Versailles. Versailles: L. Bernard. OCLC 8151727.

- Nolhac, Pierre de (1911). Histoire du Château de Versailles. Versailles Sous Louis XIV. (2 volumes). Paris: André Marty. OCLC 817037275. Vol. 2 at HathiTrust.

- Nolhac, Pierre de (1918). Histoire du Château de Versailles. Versailles au VIIIe siècle. Paris: Émile-Paul Frères. OCLC 897084052. Copy at Google Books.

- Oppermann, Fabien (2004). Images et usages du château de Versailles au XXe siècle (thesis/dissertation). Paris: École des Chartes.

- Pérouse de Montclos, Jean-Marie (1991). Versailles, translated from the French by John Goodman. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers. ISBN 9781558592285.

- Pradel, Pierre (1937). "Versailles sous le premier Empire", Revue de l'histoire de Versailles, pp. 76–94 (at Gallica).

- Solnon, Jean François (1987). La cour de France. Paris: Fayard. ISBN 9782213020150.

- Thompson, Ian (2006). The Sun King's Garden. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781582346311.

- Van der Kemp, Gérald (1976). "Remeubler Versailles", La Revue du Louvre et des musées de France, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 135–137. ISSN 0035-2608.

- Verlet, Pierre (1945). Le mobilier royal français. Paris: Editions d'art et d'histoire. OCLC 742722112.

- Verlet, Pierre (1985). Le château de Versailles (revised and updated from the 1961 edition). Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard. ISBN 9782213016009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Historical images of the Palace of Versailles. |