History of the Jews in Kurdistan

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~200,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 200,000[1][2][3][4] | |

| 400-730 families[5] | |

| Languages | |

| Northeastern Neo-Aramaic dialects (particularly Judeo-Aramaic), Kurdish (mainly Kurmanji dialects), Mizrahi Hebrew (liturgical use) and some Azeri (in Iran).[6] | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Assyrians, Mandeans | |

Jews of Kurdistan (Hebrew: יהודי כורדיסטן, Yehudei Kurdistan, lit. Jews of Kurdistan; Aramaic: אנשא דידן, Nashi Didan, lit. our people; Kurdish: Kurdên cihû) are the ancient Eastern Jewish communities, inhabiting the region known as Kurdistan in northern Mesopotamia, roughly covering parts of northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey. Their clothing and culture is similar to neighbouring Kurdish Muslims. Until their immigration to Israel in the 1940s and early 1950s, the Jews of Kurdistan lived as closed ethnic communities. The Jews of Kurdistan largely spoke Aramaic and Kurdish dialects, in particular the Kurmanji dialect in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Today, the vast majority of Kurdistan's Jews live in Israel.

History

Ancient times and classic antiquity

Tradition holds that Israelites of the tribe of Benjamin first arrived in the area of modern Kurdistan after the Assyrian conquest of the Kingdom of Israel during the 8th century BC; they were subsequently relocated to the Assyrian capital.[7] During the first century BC, the royal house of Adiabene - which, according to Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, was ethnically Assyrian and whose capital was Arbil (Aramaic: Arbala; Kurdish: Hewlêr) - was converted to Judaism.[8][9] King Monobazes, his queen Helena, and his son and successor Izates are recorded as the first proselytes.[10]

Middle Ages

According to the memoirs of Benjamin of Tudela and Pethahiah of Regensburg, there were about 100 Jewish settlements and substantial Jewish population in Kurdistan in the 12th century. Benjamin of Tudela also gives the account of David Alroi, the messianic leader from central Kurdistan, who rebelled against the king of Persia and had plans to lead the Jews back to Jerusalem. These travellers also report of well-established and wealthy Jewish communities in Mosul, which was the commercial and spiritual center of Kurdistan. Many Jews fearful of approaching crusaders, had fled from Syria and Palestine to Babylonia and Kurdistan. The Jews of Mosul enjoyed some degree of autonomy over managing their own community.[11]

Ottoman era

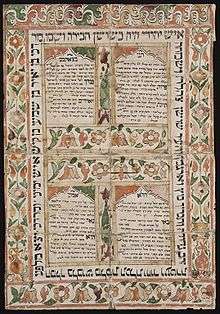

Tanna'it Asenath Barzani, who lived in Mosul from 1590 to 1670, was the daughter of Rabbi Samuel Barzani of Kurdistan. She later married Jacob Mizrahi Rabbi of Amadiyah (in Iraqi Kurdistan) who lectured at a yeshiva.[12] She was famous for her knowledge of the Torah, Talmud, Kabbalah and Jewish law. After the early death of her husband, she became the head of the yeshiva at Amadiyah, and eventually was recognized as the chief instructor of Torah in Kurdistan. She was called tanna'it (female Talmudic scholar), practiced mysticism, and was reputed to have known the secret names of God.[13] Asenath is also well known for her poetry and excellent command of the Hebrew language. She wrote a long poem of lament and petition in the traditional rhymed metrical form. Her poems are among the few examples of the early modern Hebrew texts written by women.[14]

Immigration of Kurdish Jews to the Land of Israel initiated during the late 16th century, with a community of rabbinic scholars arriving to Safed, Galilee, and a Kurdish Jewish quarter had been established there as a result. The thriving period of Safed however ended in 1660, with Druze power struggles in the region and an economic decline.

Modern times

Since the early 20th century some Kurdish Jews had been active in the Zionist movement. One of the most famous members of Lehi (Freedom Fighters of Israel) was Moshe Barazani, whose family immigrated from Iraqi Kurdistan and settled in Jerusalem in the late 1920s.

The vast majority of Kurdish Jews were forced out of Iraqi Kurdistan and evacuated to Israel in the early 1950s, together with the Iraqi Jewish community. The vast majority of the Kurdish Jews of Iranian Kurdistan relocated mostly to Israel as well, in the 1950s.

The Times of Israel reported on September 30, 2013: "Today, there are almost 200,000 Kurdish Jews in Israel, about half of whom live in Jerusalem. There are also over 30 agricultural villages throughout the country that were founded by Kurdish Jews."[15]

According to recent reports, there are between 400-730 Jewish families living in the Kurdish region. On October 18, the Kurdistan Regional Government named Sherzad Omar Mamsani, a Kurdish Jew, as the Jewish representative of the Ministry of Endowment and Religious Affairs.[5]

Historiography

One of the main problems in the history and historiography of the Jews of Kurdistan was the lack of written history and the lack of documents and historical records. During the 1930s, a German-Jewish ethnographer, Erich Brauer, began interviewing members of the community. His assistant, Raphael Patai, published the results of his research in Hebrew. The book, Yehude Kurditan: mehqar ethnographi (Jerusalem, 1940), was translated into English in the 1990s. Israeli scholar Mordechai Zaken wrote a phD dissertaion and a book, using written, archival and oral sources sources that traces and reconstructs the relationships between the Jews and their Kurdish masters or chieftains also known as Aghas). He interviewed 56 Kurdish Jews altogether conducting hundreds of interviews, thus saving their memoires from being lost forever. He interviewed Kurdish Jews mainly from six towns (Zahko, Aqrah, Amadiya, Dohuk, Sulaimaniya and Shinno/Ushno/Ushnoviyya), as well as from dozens of villages, mostly in the region of Bahdinan.[16][17] His study unveils new sources, reports and vivid tales that form a new set of historical records on the Jews and the tribal Kurdish society. His PhD thesis was commented by members of the PhD judicial committee and along with the book upon which it has been widely and interestingly translated into several Middle eastern languages, including Arabic,[18] Sorani [19] Kurmanji [20] as well as French.[21]

See also

- History of the Jews in Iraq

- Israeli–Kurdish relations

- Jewish ethnic divisions

- Kurdish people

- Assyrian people

- Syriac Christians

- Mizrahi Jews

- Jewish diaspora

- Judeo-Aramaic

- Northeastern Neo-Aramaic

- Samaria

- Seharane

- Yazidis

References

- ↑ Zivotofsky, Ari Z. (2002). "What's the Truth about...Aramaic?" (PDF). Orthodox Union. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ↑ "(p.2)" (PDF). slis.indiana.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2006.

- ↑ "Kurdish Jewish Community in Israel". Jcjcr.org. Archived from the original on 2013-07-28. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- ↑ Berman, Lazar (September 30, 2013). "Cultural pride, and unlikely guests, at Kurdish Jewish festival". timesofisrael.com.

- 1 2 Sokol, Sam (18 October 2015). "Jew appointed to official position in Iraqi Kurdistan". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "курдские евреи. Электронная еврейская энциклопедия". Eleven.co.il. 2006-12-27. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- ↑ Roth C in the Encyclopedia Judaica, p. 1296-1299 (Keter: Jerusalem 1972).

- ↑ "Irbil/Arbil" entry in the Encyclopaedia Judaica

- ↑ The Works of Josephus, Complete and Unabridged New Updated Edition Translated by William Whiston, A.M., Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc., 1987. ISBN 0913573868 (Hardcover).

- ↑ Brauer E., The Jews of Kurdistan, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 1993; Ginzberg, Louis, "The Legends of the Jews, 5th CD." in The Jewish Publication Society of America, VI.412 (Philadelphia: 1968); and http://www.eretzyisroel.org/~jkatz/kurds.html.

- ↑ Ora Schwartz-Be'eri, The Jews of Kurdistan: Daily Life, Customs, Arts and Crafts, UPNE publishers, 2000, ISBN 965-278-238-6, p.26.

- ↑ Sylvia Barack Fishman, A breath of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community, UPNE Publishers, 1995, ISBN 0-87451-706-0, p. 186

- ↑ Sally Berkovic, Straight Talk: My Dilemma As an Orthodox Jewish Woman, KTAV Publishing House, 1999, ISBN 0-88125-661-7, p.226.

- ↑ Shirley Kaufman, Galit Hasan-Rokem, Tamar Hess, Hebrew Feminist Poems from Antiquity to the Present: A Bilingual Anthology, Feminist Press, 1999, ISBN 1-55861-224-6, pp.7,9

- ↑ "Ancient pride, and unlikely guests, at Kurdish Jewish festival". timesofisrael.com.

- ↑ Joyce Blau, one of the world's leading scholars in the Kurdish languages, culture and history, suggested that "This part of Mr. Zaken’s thesis, concerning Jewish life in Bahdinan, well complements the impressive work of the pioneer ethnologist Erich Brauer."[Erich Brauer, The Jews of Kurdistan, First edition 1940, revised edition 1993, completed and edited by Raphael Patai, Wayne State University Press, Detroit])

- ↑ Jewish Subjects and their Tribal Chieftains in Kurdistan A Study in Survival By Mordechai Zaken Published by Brill: August 2007 ISBN 978-90-04-16190-0 Hardback (xxii, 364 pp.), Jewish Identities in a Changing World, 9.

- ↑ Yahud Kurdistan wa-ru'as'uhum al-qabaliyun: Dirasa fi fan al-baqa'. Transl., Su'ad M. Khader; Reviewers: Abd al-Fatah Ali Yihya and Farast Mir'i; Published by the Center for Academic Research, Beirut, 2013,

- ↑ D. MORDIXI ZAKIN, CULEKEKANY KURDISTAN, Erbil and Sulaimaniyya, 2015,

- ↑ French into Kurmanji translation of an article by Moti Zaken, "Jews, Kurds and Arabs, between 1941 and 1952", by Dr. Amr Taher Ahmed Metîn n° 148, October 2006, p. 98-123.

- ↑ Juifs, Kurdes et Arabes, entre 1941 et 1952," Errance et Terre promise: Juifs, Kurdes, Assyro-Chaldéens, etudes kurdes, revue semestrielle de recherches, 2005: 7-43, translated by Sandrine Alexie.

Bibliography

- Mordechai Zaken, "Jewish Subjects and their tribal Chieftains in Kurdistan: A study in Survival," Jewish Identities in a Changing World, 9 (Boston: Brill Publishers, 2007)

- Brauer, Erich; Patai, Raphael, The Jews of Kurdistan. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1993).

- Asenath Barzani, "Asenath's Petition", First published in Hebrew by Jacob Mann, ed., in Texts and Studies in Jewish History and Literature, vol.1, Hebrew Union College Press, Cincinnati, 1931. Translation by Peter Cole.

- Yona Sabar, The Folk Literature of the Kurdistani Jews (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982, ISBN 0300026986).

- Ariel Sabar, My Father's Paradise: A Son’s Search for His Jewish Past in Kurdish Iraq. Illustrated. 332 pp. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. Biography & study of Yona Beh Sabagha = Yona Sabar, native scholar of this community and its language. Reviewed in The New York Times, Oct. 12, 2008 and The Washington Post, Oct. 26, 2008.

- Mahir Ünsal Eriş, Kürt Yahudileri - Din, Dil, Tarih, (Kurdish Jews) In Turkish, Kalan Publishing, Ankara, 2006

- Hasan-Rokem, G., Hess, T. and Kaufman, S., Defiant Muse: Hebrew Feminist Poems from Antiquity: A Bilingual Anthology, Publisher: Feminist Press, 1999, ISBN 1-55861-223-8. (see page 65, 16th century/Kurdistan and Asenath's Petition)

- Rabbi Asenath Barzani in Jewish Storytelling Newsletter, Vol.15, No.3, Summer 2000

- The Jews of Kurdistan Yale Israel Journal, No. 6 (Spr. 2005).

- Judaism in Encyclopaedia Kurdistanica

- Sabar, Ariel. My Father's Paradise: A Son's Search for His Jewish Past in Kurdish Iraq

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kurdish Jews. |