Hippodrama

Hippodrama, or horse drama, is a genre of theatrical show blending circus horsemanship display with popular melodrama theatre. Evolving from earlier equestrian circus, pioneered by Philip Astley in the 1760s,[1] it relied on drama plays written specifically for the genre; trained horses were considered actors along with humans and were even awarded leading roles.[2] Anthony Hippisley-Coxe described hippodrama as "a bastard entertainment born of a misalliance between the circus and the theatre ... that actually inhibited the development of the circus".[3]

History

Horses appeared in Western European theater in the second half of the 18th century, both on stage and in aerial stunts (flying Pegasus).[2] Hippodrama emerged in the turn of 19th century in England, introduced by Philip Astley. At this time, the Licensing Act of 1737 was in effect. This act only allowed three theaters to perform “legitimate theater.” These theaters included Covent Garden, Drury Lane, and the summer theatre in the Haymarket. These theaters had patents on real drama. Other theaters, such as Astley’s Amphitheater and the Royal Circus, only had licenses for “public dancing and music” and “for other public entertainments of the like kind”.[4] Astley’s horse acts in his circus were allowed within his license. However, Astley wanted to produce shows more like “legitimate theater.” He soon realized that he could produce real drama as long as the drama was performed on horseback. Thus, hippodrama was born. He adapted common stories and plays in a way where they could be performed on horses. Not only that, but the horses were the main actors. The horses had their own business, or leading actions, to perform that helped carry out the plot.[5] Also at this time, gradual closing of country fairs and discharge of cavalrymen and horse grooms after the end of the Continental Wars[2] provided both experienced staff and public interest to the new show.

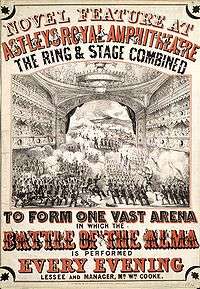

The first hippodrama premiered in 1803 in London at Astley's Amphitheatre, Royal Circus and Olympic Pavilion; and in Paris at Cirque Olympique,[2] where 36 horse riders could perform simultaneously.[1] Theatres built for hippodramas combined proscenium stage with dirt-floored riding arena separated by orchestra pit; scene and arena were connected by ramps, forming a single performing space.[1] The Circus of Pepin and Breschard presented Don Quixote de la Mancha "on horseback and on foot, with combats" in New York City on August 12, 1809.[6] Pepin and Breschard's company presented hippodramas in the newly formed United States from at least 1809 until 1815. Christoph de Bach produced similar entertainment in Vienna.[2] Astley's 1810 financial success with The Blood Red Knight persuaded the reluctant management of Covent Garden and Drury Lane theatres to join the lucrative business.[2] Hippodrama plays, tailored for the masses, revolved around colourful Eastern subjects like Timour the Tartar or Mazeppa, or the Wild Horse of Tartary and the European military past (Marlborough's Heroic Deeds).[2] Mazeppa, first staged in England in 1823, became a hit of Astley's Amphitheater in 1831 and was performed by travelling companies in the United States from 1833; in 1860s it became a trademark show for Adah Isaacs Menken.[7] Adaptations of William Shakespeare (Richard III) were another common choice.[1]

The new genre spread to the United States after the end of the Napoleonic Wars; the Lafayette Circus in New York City, inaugurated in 1825, was the first American theatre building specifically designed for hippodrama, followed by the Philadelphia Amphitheater and the Baltimore Roman Amphitheatre.[1] Hippodrama shows attracted the lower classes, labourers and seamen,[8] "ready to riot at the slightest provocations";[9] "in fact, much of recorded rowdyism of the mid-1820s in New York City took place at Lafayette Circus.[8]

Hippodrama also traveled all the way to Australia. Hippodromes were built in Sydney and Melbourne in the 1850s. “The year 1854 was also the year in which the Crimean War began, so Lewis’s mention of the military value of sport and drama was a pointed one; hippodramas by implication assisted in encouraging men to keep themselves fit and trained in military skills such as horse-riding” (Fotheringham 12). However, hippodrama was not as big in Australia as it was in England. It did leave an impact, though. Hippodrama helped change Australian theater building designs. In order to accommodate the horses, there had to be a way for the horses to get onstage. So, the theaters started to build ramps leading up to the stage. Also, the stages had to be big enough to hold a circus ring. From then on, the stages were built bigger.[10]

The Equestrian Circus in Saint Petersburg, Russia was built by Alberto Cavos in 1847.

The American Hengler's Circus prospered in the 1850s under the heading of Hengler's Colossal Hippodrama,[11] but elsewhere popularity of the genre faded by the middle of the century.[2] It was revived in France under Napoleon III, especially with the 1863 production of the Battle of Marengo and in 1880 Michel Strogoff.[2] The United States saw a brief revival of the genre in the late 1880s and 1890s, helped by the invention of a treadmill machine for imitating horse races on stage.[2] Film, introduced at the turn of the 20th century, finally replaced hippodrama as the show for the masses.[2]

In modern times

In recent times, the Cavalia circus/show/production company has produced a well-received modern hippodrama which tours internationally, using as many as 30 horses per show and playing for up to two thousand people at a time.[12]

A modern one-of-a-kind hippodrama directed by Franz Abraham, an equestrian reenactment of Ben Hur, took place at the O2 arena, London on September 15, 2009. The show employed one hundred animals (including thirty-two horses) and four hundred people.[13][14][15][16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 McArthur, p. 21

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Banham, p. 488

- ↑ Hippisley-Coxe, A Seat at the Circus (1951, rev. ed. 1980), as cited by Stoddard, p. 17

- ↑ (Saxon, “Circus as Theatre” 301)

- ↑ (Saxon, Enter 6-7)

- ↑ New York Mercantile Advertiser, August 12, 1809

- ↑ McArthur, pp. 21-22

- 1 2 Gilje, p. 252

- ↑ Gilje, p. 251

- ↑ (Fotheringham 11-14)

- ↑ Stoddard, pp. 39-40

- ↑ "Big-top horse show 'Cavalia' gallops into Chicago". www.chicagotribune.com. June 3, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ↑ "Ben Hur comes to Greenwich: Spectacular all-action live show to premiere at O2 Arena". London: Daily Mail. November 6, 2008. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- ↑ "Chariots of fire as Ben Hur comes to The O2". www.thelondonpaper.com. May 11, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- ↑ Review of performance

- ↑ Follow up review

Sources

- Saxon, Arthur Hartley (1968). Enter foot and horse; a history of hippodrama in England and France. Yale University Press. LCCN 68027764.

- Saxon, Arthur Hartley (1975). "The Circus as Theatre: Astley's and Its Actors in the Age of Romanticism.". Educational Theatre Journal. 27 (3): 299–312.

- Fotheringham, Richard (1992). Sport in Australian Drama. Cambridge, England: Cambridge UP.

- Banham, Martin (1995). The Cambridge guide to theatre. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521434378, ISBN 978-0-521-43437-9.

- Gilje, Paul A. (1987). The road to mobocracy: popular disorder in New York City, 1763-1834. UNC Press. ISBN 0807841986, ISBN 978-0-8078-4198-3.

- McArthur, Benjamin (2007). The man who was Rip van Winkle: Joseph Jefferson and nineteenth-century American theatre. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300122322, ISBN 978-0-300-12232-9.

- Stoddard, Helen (2000). Rings of desire: circus history and representation. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719052343, ISBN 978-0-7190-5234-7.