Hill 303 massacre

| Hill 303 massacre | |

|---|---|

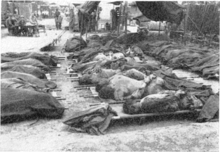

Bodies of massacre victims gathered near Waegwan, South Korea, many with their hands still bound | |

| Location | Hill 303, Waegwan, South Korea |

| Date |

August 17, 1950 14:00 (KST) |

| Target | U.S. Army prisoners of war |

Attack type | mass execution |

| Deaths | 42 prisoners executed |

Non-fatal injuries | 4–5 prisoners wounded |

| Perpetrators | North Korean army soldiers |

The Hill 303 massacre (Korean: 303 고지 학살 사건) was a war crime that took place during the Korean War on August 17, 1950, on a hill above Waegwan, South Korea. Forty-one captured United States Army prisoners of war were shot and killed by troops of the North Korean army during one of the smaller engagements of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter.

Operating near Taegu during the Battle of Taegu, elements of the U.S. Army's 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division were surrounded by North Korean troops crossing the Naktong River at Hill 303. Most of the U.S. troops were able to escape but one platoon of mortar operators misidentified North Korean troops as South Korean army reinforcements and was captured. North Korean troops held the Americans on the hill and initially tried to move them across the river and out of the battle, but they were unable to do so because of heavy counterattack. American forces eventually broke the North Korean advance, routing the force. As the North Koreans began to retreat one of their officers ordered the prisoners to be shot so they would not slow the North Koreans down.

The massacre provoked a response from both sides in the conflict. U.S. commanders broadcast radio messages and dropped leaflets demanding the senior North Korean commanders be held responsible for the atrocity. The North Korean commanders, concerned about the way their soldiers were treating prisoners of war, laid out stricter guidelines for handling enemy captives. Memorials were later constructed on Hill 303 by troops at nearby Camp Carroll, to honor the victims of the massacre.

Background

Korean War begins

Following the invasion of the South Korea by North Korea, and the subsequent outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, 1950, the United Nations decided to enter the conflict on behalf of South Korea. The United States, a member of the U.N., subsequently committed ground forces to the Korean Peninsula with the goal of fighting back the North Korean invasion and to prevent South Korea from collapsing.[1]

The 24th Infantry Division was the first U.S. unit sent into Korea. The unit was to take the initial "shock" of North Korean advances, delaying much larger North Korean units to buy time to allow reinforcements to arrive.[2] The division was consequently alone for several weeks as it attempted to delay the North Koreans, making time for the 1st Cavalry and the 7th and 25th Infantry Divisions, along with other Eighth United States Army supporting units, to move into position.[2] Advance elements of the 24th Infantry, known as Task Force Smith, were badly defeated in the Battle of Osan on July 5, the first encounter between American and North Korean forces.[3] For the first month after this defeat, the 24th Infantry was repeatedly defeated and forced south by superior North Korean numbers and equipment.[4][5] The regiments of the 24th Infantry were systematically pushed south in engagements around Chochiwon, Chonan, and Pyongtaek.[4] The 24th made a final stand in the Battle of Taejon, where it was almost completely destroyed but delayed North Korean forces until July 20.[6] By that time, the Eighth Army's force of combat troops were roughly equal to North Korean forces attacking the region, with new UN units arriving every day.[7]

With Taejon captured, North Korean forces began surrounding the Pusan Perimeter in an attempt to envelop it. They advanced on UN positions with armor and superior numbers, repeatedly defeating U.S. and South Korean forces and forcing them further south.[8]

Pusan Perimeter at Taegu

In the meantime, Eighth Army commander Gen. Walton Walker had established Taegu as the Eighth Army's headquarters. Right at the center of the Pusan Perimeter, Taegu stood at the entrance to the Naktong River valley, an area where large numbers of North Korean forces could advance while supporting one another. The natural barriers provided by the Naktong River to the south and the mountainous terrain to the north converged around Taegu, which was also the major transportation hub and last major South Korean city aside from Pusan itself to remain in UN hands.[9] From south to north, the city was defended by the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division and the ROK 1st Division and ROK 6th Division of ROK II Corps. 1st Cavalry Division, under the command of Maj. Gen. Hobart R. Gay, was spread out in a line along the Naktong River to the south, with its 5th Cavalry and 8th Cavalry regiments holding a 24-kilometre (15 mi) line along the river and the 7th Cavalry in reserve along with artillery forces, ready to reinforce anywhere a crossing could be attempted.[10]

Five North Korean divisions massed to oppose the UN at Taegu; from south to north, the 10th,[11] 3rd, 15th, 13th,[12] and 1st Divisions occupied a line from Tuksong-dong and around Waegwan to Kunwi. The North Korean army planned to use the natural corridor of the Naktong valley from Sangju to Taegu as its main axis of attack for the next push south.[13] Elements of the NK 105th Armored Division were also supporting the attack.[10]

Beginning August 5, these divisions initiated numerous crossing attempts to assault the UN forces on the other side of the river in an attempt to capture Taegu and collapse the final UN defensive line. The U.S. forces were successful in repelling North Korean advances thanks to training and support, but forces in the South Korean sectors were not as successful.[14] During this time, isolated reports and rumors of war crimes committed by both sides began to surface.[15]

Military geography

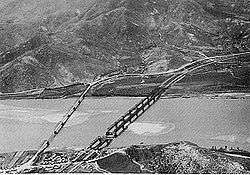

Hill 303 forms an elongated oval 2 miles (3.2 km) long on a northeast-southwest axis with an extreme elevation of 994 feet (303 m). It is the first hill mass north of Waegwan and its southern slope comes down to the edge of the town. The hill grants observation of Waegwan, a network of roads running out of the town, the railroad and highway bridges across the river at that point, and long stretches of the river valley to the north and to the south. Its western slope terminates at the east bank of the Naktong River. From Waegwan a road runs north and south along the east bank of the Naktong, another northeast through the mountains toward Tabu-dong, and still another southeast toward Taegu. Hill 303 was a critical terrain feature in control of the main Pusan-Seoul railroad and highway crossing of the Naktong, as well as of Waegwan itself.[16]

Massacre

The exact details of the massacre are sketchy, and based on the accounts of four U.S. soldiers who survived the event. Three captured North Korean soldiers were pointed out by the survivors as participants in the killings, and these three also gave conflicting accounts of what happened.[17]

North Korean advance

The northernmost unit of the 1st Cavalry Division's sector was G Company of the 5th Cavalry Regiment. It held Hill 303, the furthest position on the Eighth Army's extreme right flank.[18] To the north lay the ROK 1st Division, the first unit in the line of the South Korean Army.[19]

For several days UN intelligence sources had reported heavy North Korean concentrations across the Naktong, opposite the ROK 1st Division. Early in the morning on August 14, a North Korean regiment crossed the Naktong 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Waegwan into the ROK 1st Division sector through an underwater bridge. Shortly after midnight ROK forces on the high ground just north of the US-ROK Army boundary were attacked by this force. After daylight an air strike partially destroyed the underwater bridge. The North Korean attack spread south and by 12:00 (KST), North Korean small-arms fire fell on G Company, 5th Cavalry Regiment, on Hill 303. Instead of moving east into the mountains as other landings had, this force turned south and headed for Waegwan.[20]

At 03:30[18] the morning on August 15, G Company troops on Hill 303 spotted 50 North Korean infantry supported by two T-34 tanks moving south along the river road at the base of the hill. They also spotted another column moving to their rear, which quickly engaged F Company with small-arms fire. In order to escape the enemy encirclement, F Company withdrew south, but G Company did not. By 08:30 the North Koreans had completely surrounded it and a supporting platoon of H Company mortarmen on Hill 303. At this point the force on the hill was cut off from the rest of the American force. A relief column, composed of B Company, 5th Cavalry, and a platoon of U.S. tanks, tried to reach G Company but was unable to penetrate the North Korean force that was surrounding Hill 303.[19]

U.S. forces captured

According to survivor accounts, before dawn on August 15 the H Company mortar platoon became aware of enemy activity near Hill 303.[18][21] The platoon leader telephoned G Company, 5th Cavalry, which informed him a platoon of 60 South Korean troops would come to reinforce the mortar platoon.[18] Later in the morning the platoon saw two North Korean T-34s followed by 200 or more enemy soldiers on the road below them. A little later a group of Koreans appeared on the slope.[21] A patrol going to meet the climbing Korean troops called out and received in reply a blast of gunfire from automatic weapons.[18] The mortar platoon leader, Lt. Jack Hudspeth, believed they were friendly.[22] Some of the Americans realized that the advancing troops were North Korean and were going to open up on them according to former Pvt. Fred Ryan and Pvt. Roy Manring, when they revisited the old mortar position in 1999. However, Lt. Hudspeth ordered them not to fire and even threatened them with a court-martial if they did. The rest of the watching Americans were not convinced that the new arrivals were enemy soldiers until the red stars became clearly visible on their field caps.[21] By that time, they were extremely close to the American positions.[23] The North Korean troops came right up to the foxholes without either side firing a shot.[21] Hudspeth ordered his platoon to surrender without a fight as it was far outnumbered and outgunned.[22] The North Koreans quickly took all 31 of the mortarmen captive.[21][24][25] One account, however, said 42 men were captured on the hill.[26]

They were captured by the 4th Company, 2nd Battalion, 206th Mechanized Infantry Regiment of the NK 105th Armored Division. The North Korean troops marched their prisoners down the hill after taking their weapons and valuables.[18][21] In a nearby orchard, they tied the prisoners' hands behind their backs, took some of their clothing and removed their shoes.[22][25] They told the American POWs that they would be sent to the prisoner-of-war camp in Seoul if they behaved well.[21]

Imprisonment

The original captors did not stay in continuous possession of the prisoners throughout the next two days. There is some evidence that elements of the NK 3rd Division guarded them after capture. During the first night of captivity the North Koreans gave the American prisoners water, fruit and cigarettes.[27] Survivors claimed this was the only food and water the North Koreans gave them over the three days of their imprisonment.[28] The Americans dug holes in the sand to get more water to drink.[23] The North Koreans intended to move them across the Naktong that night, but American artillery fire on the Naktong River crossing sites prevented safe movement. During the night two of the Americans loosened their bindings, causing a brief commotion. North Korean soldiers threatened to shoot the Americans but, according to one survivor's account, a North Korean officer shot one of his own men for threatening this.[27] Two captured American officers—Lt. Hudspeth, the platoon leader of the Mortar Platoon, and Lt. Cecil Newman, who was a forward artillery observer, were seen conferring with each other about an escape plan according to Pvt. Fred Ryan. Both escaped during the night but were captured and executed. The North Koreans attempted to keep the Americans hidden during the day and move them at night, but attacks by American forces made this difficult.[23][24]

The next day, August 16, the prisoners were moved with their guards. One of the mortarmen, Cpl. Roy L. Day Jr., spoke Japanese and was able to converse with some of the North Koreans. That afternoon he overheard a North Korean lieutenant say that they would kill the prisoners if other American forces advanced too close.[18][23][27] Later that day other American forces began to assault Hill 303 to retake the position. B Company and several American tanks tried a second time to retake the hill, now estimated to contain a 700-man battalion. The 61st Field Artillery Battalion and elements of the 82nd Field Artillery Battalion fired on the hill during the day. That night, G Company succeeded in escaping from Hill 303.[19] Guards took away five of the American prisoners; the others did not know what became of them.[27]

Before dawn on August 17, troops from both the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 5th Cavalry Regiment, supported by A Company of the 70th Tank Battalion, attacked Hill 303, but heavy North Korean mortar fire stopped them at the edge of Waegwan. During the morning, American artillery heavily bombarded the North Korean positions on the hill.[20] Throughout the morning of August 17 the North Korean guards exchanged fire with U.S. troops attempting to rescue the prisoners. Around 12:00 the North Korean unit holding the Americans placed them in a gully on the hill with a light company of 50 guards.[22][27] Several more American prisoners were added to the group during the day, bringing the number of prisoners on Hill 303 to 45.[20] However, one survivor estimated that the number of prisoners in total was 67, and that the balance of the prisoners were executed on August 15 or 16.[26]

Execution

At 14:00 on August 17, a UN air strike took place, attacking the hill with napalm, bombs, rockets and machine guns.[29] At this time a North Korean officer said that American soldiers were closing in on them and they could not continue to hold the prisoners.[27] The officer ordered the men shot, and the North Koreans then fired into the kneeling Americans as they rested in the gully.[25] One of the North Koreans who was later captured said all or most of the 50 guards participated,[27][30] but some of the survivors said only a group of 14 North Korean guards, directed by their non-commissioned officers, fired into them with PPSh-41 "burp guns".[23][24] Before all the North Korean soldiers left the area, some returned to the ravine and shot survivors of the initial massacre.[23][27] Only four[22][24] or five[23][26][31] of the men in this group survived, by hiding under the dead bodies of others.[22] In all, 41 American prisoners were killed in the ravine.[27] The bulk of these men—26 in all—were from the mortar platoon but prisoners captured elsewhere were also among them.[32]

The U.S. air strike and artillery bombardment pushed North Korean forces off the hill. After the strike, at 15:30, the infantry attacked up the hill unopposed and secured it by 16:30. The combined strength of E and F Companies atop the hill was about 60 men. The artillery and the air strike killed and wounded an estimated 500 enemy troops on Hill 303, with survivors fleeing in complete disorder.[20] Two of the massacre survivors making their way down the hill to meet the counterattacking force were fired upon before they could establish their identity, but not hit.[22][27] American forces of the 5th Cavalry Regiment quickly discovered the bodies of the American prisoners with machine-gun wounds, hands still bound behind their backs.[33]

That night, near Waegwan, North Korean anti-tank fire hit and knocked out two tanks of the 70th Tank Battalion. The next day, August 18, American troops found the bodies of six members of the tank crews showing indications that they had been captured and executed in the same manner as the men on Hill 303.[27]

Aftermath

U.S. response

The incident on Hill 303 led UN commander, General Douglas MacArthur, to broadcast to the North Korean Army on August 20, denouncing the atrocities. The U.S. Air Force dropped many leaflets over enemy territory, addressed to North Korean commanders. MacArthur warned that he would hold North Korea's senior military leaders responsible for the event and any other war crimes.[27][31]

Inertia on your part and on the part of your senior field commanders in the discharge of this grave and universally recognized command responsibility may only be construed as a condonation and encouragement of such outrage, for which if not promptly corrected I shall hold you and your commanders criminally accountable under the rules and precedents of war.

— General of the Army Douglas MacArthur's closing remark in his broadcast to the North Korean Army on the incident.[34]

The incident at Hill 303 would be only one of the first of a series of atrocities the U.S. forces accused North Korean soldiers of committing.[33][35] In late 1953 the United States Senate Committee on Government Operations, led by Joseph McCarthy, conducted an investigation of up to 1,800 reported incidents of war crimes allegedly committed throughout the Korean War. The Hill 303 massacre was one of the first to be investigated.[36] Survivors of the incident were called to testify before the committee, and the U.S. government concluded that the North Korean army violated the terms of the Geneva Convention, and condemned its actions.[22][37]

North Korean response

Historians agree there is no evidence that the North Korean High Command sanctioned the shooting of prisoners during the early phase of the war.[33] The Hill 303 massacre and similar atrocities are believed to have been conducted by "uncontrolled small units, by vindictive individuals, or because of unfavorable and increasingly desperate situations confronting the captors."[31][34] T. R. Fehrenbach, a military historian, wrote in his analysis of the event that North Korean troops committing these events were likely accustomed to torture and execution of prisoners due to decades of rule by oppressive armies of the Empire of Japan up until World War II.[38]

On July 28, 1950, Gen. Lee Yong Ho, commander of the NK 3rd Division, had transmitted an order pertaining to the treatment of prisoners of war, signed by Kim Chaek, Commander-in-Chief, and Choi Yong-kun, commander of the Advanced General Headquarters of the North Korean Army, which stated killing prisoners of war was "strictly prohibited." He directed individual units' Cultural Sections to inform the division's troops of the rule.[34]

Documents captured after the event showed that North Korean Army leaders were aware of—and concerned about—the conduct of some of their soldiers. An order issued by the Cultural Section of the NK 2nd Division dated August 16 said, in part, "Some of us are still slaughtering enemy troops that come to surrender. Therefore, the responsibility of teaching the soldiers to take prisoners of war and to treat them kindly rests on the Political Section of each unit."[34]

Monument

The story quickly gained media attention in the United States, and the survivors' accounts received a great deal of coverage[39] including prominent magazines such as Time[22] and Life.[23] In the years following the Korean War, the U.S. Army established a permanent garrison in Waegwan, Camp Carroll, which is located near the base of Hill 303. The incident was largely forgotten until Lt. David Kangas read about the incident in the book "South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu" while stationed at Camp Carroll in 1985, and after checking with various US Army and local sources he realized that the location of the massacre was unknown. He then obtained battle records through the National Archives to pinpoint the actual location of the POW massacre and then began a quest to find the whereabouts of the remaining survivors. The original memorial for the POWs was emplaced in 1990 in front of the garrison headquarters, although none of the American survivors were located by Kangas until 1991. In 1999 Fred Ryan and Roy Manring, two of the three surviving POWs, were invited to attend a ceremony at the execution site. Both Ryan and Manring as well as James Rudd, the third surviving POW, had long been denied VA compensation claims for their severe injuries incurred during the execution because they had never been officially designated as Prisoners of War by the US Army. Later the base garrison at Camp Carroll raised funds to construct a much larger memorial at the actual massacre site on Hill 303. South Korean military and civilians around Waegwan contributed to the funds for this memorial.[40] The original memorial was placed on the hill on August 17, 2003. In 2009 soldiers of the U.S. 501st Sustainment Brigade began to gather funds for a second, larger monument on the hill. With the assistance of South Korean veterans, politicians and local citizens, the second monument was flown to the top of the hill by a U.S. Army CH-47 Chinook helicopter on May 26, 2010, in preparation for the 60th anniversary of the event.[41] An annual memorial service is held on the hill to commemorate the deaths of the troops on Hill 303. Troops garrisoned at Camp Carroll scale the hill and place flowers at the monument as a part of this service.[28]

See also

- List of massacres in South Korea

- Bodo League massacre

- Chaplain-Medic massacre

- No Gun Ri Massacre

- Seoul National University Hospital Massacre

References

Citations

- ↑ Varhola 2000, p. 3.

- 1 2 Alexander 2003, p. 52.

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 15.

- 1 2 Varhola 2000, p. 4.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 90.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 105.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 103.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 222.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 335.

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 337.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 253.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 254.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 336.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 338.

- ↑ Chinnery 2001, p. 22.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 345.

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chinnery 2001, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1998, p. 346.

- 1 2 3 4 Appleman 1998, p. 347.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Appleman 1998, p. 348.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bell 1950.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Walker 1950.

- 1 2 3 4 McCarthy 1954, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Millett 2010, p. 161.

- 1 2 3 Ecker 2004, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Appleman 1998, p. 349.

- 1 2 Lucas.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 143.

- ↑ Chinnery 2001, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 Alexander 2003, p. 144.

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 136.

- 1 2 3 4 Appleman 1998, p. 350.

- ↑ Millett 2010, p. 160.

- ↑ McCarthy 1954, p. 1.

- ↑ McCarthy 1954, p. 16.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 137.

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 15.

- ↑ Fisher 2003.

- ↑ Garcia 2010.

Sources

- Alexander, Bevin (2003). Korea: The First War we Lost. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7.

- Appleman, Roy E. (1998). South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War. Department of the Army. ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0.

- Bell, James (August 28, 1950). "Massacre at Hill 303". Time. ISSN 0040-781X.

- Catchpole, Brian (2001). The Korean War. Robinson Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4.

- Chinnery, Philip D. (2001). Korean Atrocity: Forgotten War Crimes 1950–1953. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-473-9.

- Ecker, Richard E. (2004). Battles of the Korean War: A Chronology, with Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures & Medal of Honor Citations. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-1980-7.

- Fehrenbach, T.R. (2001). This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History – Fiftieth Anniversary Edition. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-57488-334-3.

- McCarthy, Joseph; Karl E. Mundt, John L. McLellan, Margaret C. Smith; et al. (1954). "Korean War Atrocities Report of the Committee on Government Operations" (PDF). US Government Printing Office. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- Millett, Allan R. (2010). The War for Korea, 1950–1951: They Came from the North. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1709-8.

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000). Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4.

- Walker, Hank (September 4, 1950). "What the corporal saw...". Life. 29 (10). ISSN 0024-3019.

Online sources

- Lucas, Adrianna N. "Soldiers scale Hill 303 in honor of fallen comrades". Eighth United States Army. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- Fisher, Franklin (August 22, 2003). "Army honors three Koreans with Good Neighbor awards". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- Garcia, Megan (June 24, 2010). "US, Korean Soldiers remembered at Hill 303" (PDF). Eighth United States Army. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

Coordinates: 35°59′N 128°24′E / 35.983°N 128.400°E