Healey Building

|

Healey Building | |

|

Healey Building, West Tower | |

| |

| Location | 57 Forsyth St., Atlanta, Georgia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33°45′22″N 84°23′23″W / 33.75611°N 84.38972°WCoordinates: 33°45′22″N 84°23′23″W / 33.75611°N 84.38972°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1913 |

| Architect | Morgan & Dillon; Downing,Walter T. |

| Architectural style | Late Gothic Revival, Skyscraper |

| NRHP Reference # | 77000429[1] |

| Added to NRHP | August 12, 1977 |

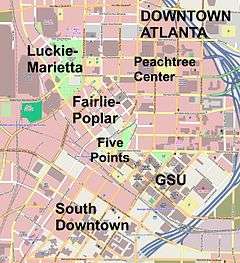

The Healey Building, at 57 Forsyth Street NW, in the Fairlie-Poplar district of Atlanta, was the last major "skyscraper" built during the first great burst of multi-story commercial construction preceding World War I. In fact, it was World War I, which led to the alteration of the original design, which called for twin towers connected by a rotunda. Only the west tower and rotunda were constructed before World War I broke out. The death in 1920 of William Healey forestalled continuation of the project after the war. According to Dr. Elizabeth Lyon in her National Register of Historic Places nomination, "The Healey Building has an elegance and high shouldered dignity which make it outstanding among its contemporaries." Those contemporaries include the Chandler, the Flatiron and Hurt Buildings among others. Although certainly distinctive for its physical appearance and location, the Healey Building is also associated with significant individuals in Atlanta history. Thomas G. Healey and his son William T. Healey were political and business leaders in the city - in the case of Thomas, dating back to pre-Civil War times. Their contributions to Atlanta's architectural history as contractors and businessmen are numerous and significant. In addition to the Healeys, the architects Thomas Morgan, John Dillon, and Walter T. Downing have left an important body of works as monuments to their skill and abilities.

Born in 1818, Thomas G. Healey moved to Savannah, Ga. in 1846, from Connecticut. A few years later, he was in Atlanta working in the brick-making business and as builder/contractor in partnership with Maxwell Berry. Healey and Berry were responsible for a number of Atlanta churches and government buildings prior to the war, including the Church of the Immaculate Conception, Trinity Methodist Church, First Presbyterian Church, and the United States Custom House (later City Hall). Following the destruction of the war, Healey was in the perfect business for the construction boom of the late 1800s, which rebuilt Atlanta. As his wealth accumulated, T. G. Healey became active in politics and other business ventures. One investment was in land, including the northwest corner of Marietta and Peachtree Streets where he built the first Healey Building. This location was the place where Atlanta's first elections were held in 1848 and where T. G. Healey's grandsons (William and Oliver) built the William-Oliver Building in 1930. From 1877 to 1882, Healey was president of the Atlanta Gas Light Company. In the 1880s, he was president of the West End and Atlanta Street Railroad Company, on the Executive Committee of the 1881 International Cotton Exhibition, and a Director of Joel Hurt's Atlanta Home Insurance Company (of which he was a purchaser of $5,000 in original stock). Politically, he was city alderman- at-large (1881) and mayor pro tem (1884). By 1889, the Atlanta Constitution was estimating Healey's wealth at between $500,000 and $1,000,000 - thus making him one of the fifteen richest men in the city. During this period, William T. Healey joined his father in his many business ventures, which still included brick making and real estate development. Among their joint enterprises were the Atlanta Car Works streetcar line (1892) and the development of a mineral water property, Austell Lithia Springs. After Thomas Healey's death in 1897, William carried on the family businesses, which came to include the new Healey Building of 1914. Excavations took most of 1913 and the project became known as "Healey's Hole," with seventy (seven feet square) wells filled with concrete reaching a depth of sixty feet.

The 16-story building was completed in 1914, at the end of Atlanta's first skyscraper era (1893-1918). Constructed of stone and embellished with terra-cotta, the wide, rectangular building achieves its vertical appearance from clustered piers which rise uninterrupted from the two- story base to the cornice. The neo-Gothic elements of the exterior detailing have been placed primarily at the base of the roofline. Pointed arches and tracery are employed to define the entrances and the storefronts; a heavy, ornate cornice which denotes the influence of Chicago architect Louis Sullivan caps the building. As the detailing of the street-level display windows is noteworthy, so is the unusual fenestration of the upper floors. Windows of different sizes and proportions are used: narrow, paired double-hung windows in the central bays of the long facades and wide, single, double-hung windows for the remainder of the building. The original plan for the Healey Building called for two matching skyscrapers on either side of a central dome. An arcade system was integrated into the plan that would allow pedestrian access through the buildings to Broad Street, Forsyth Street and Walton Street. This system, which was constructed along with the dome and one tower in 1914, is found in the skyscraper designs of pioneer Chicago architect Daniel H. Burnham. In northern cities such as Chicago and Buffalo, Burnham's arcades provided protection from severe winter weather. Atlanta office workers have often used the Healey arcades as a cut through on rainy days. The ground level interior space lined with shops became an important public space rather than merely an enclosed lobby.

William Healey chose the firm of Morgan and Dillon to design his new building on Forsyth Street. In 1898, the firm's antecedent Bruce and Morgan had designed the Austell Building at 10 Forsyth Street and the Prudential Building on Broad Street, the city's first completely steel- framed skyscraper. From that time on, according to Dr. Elizabeth Lyon in her study of Atlanta's commercial architecture, Bruce and Morgan and its successor Morgan and Dillon were "the predominant architects designing large commercial structures" in the city. Their other works included the Empire Building, the Century Building, the Fourth National Bank, and the Third National Bank Building at Broad and Marietta Streets. The latter building was designed with the services of Walter Downing. Thomas Henry Morgan was born in Syracuse, New York in 1857 but later attended the University of Tennessee. He came to Atlanta in 1878 as a draftsman with the architectural firm of Parkins and Bruce. In 1882, the firm became Bruce and Morgan until 1904 when Bruce retired. It was at this time that Morgan formed his partnership with John R. Dillon. Among their buildings were the original Henrietta Egleston Hospital, J. P. Allen Department Store, Fulton County Courthouse (with A. Ten Eyck Brown), Fulton County Alms House, numerous schools and firehouses, as well as various college buildings at Georgia Tech, Agnes Scott, and Oglethorpe. Morgan appears to have been the salesman of the firm and was certainly prominent socially. He was a charter member of the prestigious Piedmont Driving Club, Capital City Club, and the Gate City Guard. Professionally, he was the first president of the Atlanta Chapter of the American Institute of Architects and wrote the state law creating a State Board to examine and register architects. Not surprisingly, he served as the first president of the State Board. As already mentioned, Morgan and Dillon sometimes used Walter Downing as an associate of the firm. Downing was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1865 and moved to Atlanta in 1881. He began his study of architecture in the office of L. B. Wheeler in 1885, establishing his own business in 1890. Downing was well enough known to be the only Atlanta architect to design an exhibition hall for the 1895 Cotton States Exposition, the Fine Arts Building. A picture of this building shows a Beaux-Arts design with heavily carved and decorative friezes, columned front, balustrades, and one-story, matching wings with bowed side porticoes. In a letter from Horace Bradley (New York promoter of the exposition) to Downing, the former states that the famous painter James MacNeill Whistler greatly admired the design from a photograph and specifically asked who the architect was. Downing went on to design the Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (335 Peachtree Center Blvd.), First Presbyterian Church (1328 Peachtree Street), Trinity Methodist Church (265 Washington Street), the Gay House (98 Currier Street), and the Wimbush House (1150 Peachtree Street and longtime home of the Atlanta Woman's Club). He also designed a famous Atlanta landmark for many years, the Flag Pole at Five Points. In 1898, W. T. Downing became a member of the American Institute of Architects and in 1909 was elected president of the Atlanta chapter of that organization. He was also responsible for the house of Hattie High at Peachtree and Fifteenth Streets, first home of what was to become the High Museum. As a gift to the city from Mrs. High, Downing designed a fountain across the street from her house.

The Healey Building remained in the Healey family until 1972 when it was sold for $3.2 million to Edward Elson and Morris Abram. In 1976, the building was named to the National Register of Historic Places (Ref #77000429). Five years later, German entrepreneur Guenter Kaussen purchased the structure. By 1985, only sixteen percent of the office space remained in use and the building was bought from Kaussen's estate for $8 million by Healey Building Associates Ltd., a joint venture by the Dutch firm of Euram Resources and the Dutch bank Staal Bankers, N.V. In 1987, the Healey Building underwent an almost $12 million renovation under the direction of the architectural firm of Stang and Newdow. Prior to the renovation, it was reported that three truckloads of "trash" were removed from the Healey's basement three times daily for three months. Thus was "reborn" an Atlanta landmark.

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- Atlanta's Lasting Landmarks, Atlanta Urban Design Commission, 1987.

- Garrett, Franklin. Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of Its People and Events, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1982.

- Lyon, Elizabeth M. Business Buildings in Atlanta: A Study in Urban Growth and Form, Ann Arbor, Mi.: University Microfilm, 1971.

- Martin, Thomas. Atlanta and Its Builders, Century Memorial Publishing Co., 1901. Articles

- Crannell, Carlyn G. "The High Heritage," The Atlanta Historical Journal XXIII #4 (Winter 1979- 80), 71-84.

- Edge, Sarah S. "The Atlanta Home Insurance Company," The Atlanta Historical Bulletin, IX # 37, 77-94.

- King, Jr., Spencer Bidwell. "Atlanta's Early Builders," The Atlanta Historical Bulletin, XV # 4, 88- 96.

- Mitchell, Stephens. "A Comparison of Tax Returns for the Years 1868- 1909-1936," The Atlanta Historical Bulletin, VII # 28 (Sept. 1943), 89-167.

- Salter, Sallye. "Healey project nearly finished," The Atlanta Constitution, March 23, 1987, p. 2- C.

- Sinderman, Martin. "Study skyscraper built on 'Healey Hole'," Atlanta Business Chronicle, July 4, 1989, p. 7B.

- "Thomas Henry Morgan," The Atlanta Historical Bulletin, VII #28 (Sept. 1943), 87-88.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Healey Building. |