Hate crime laws in the United States

Hate crime laws in the United States protect against hate crimes (also known as bias crimes) motivated by enmity or animus against a protected class. Although state laws vary, current statutes permit federal prosecution of hate crimes committed on the basis of a person's protected characteristics of race, religion, ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, political views and disability. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ)/FBI, as well as campus security authorities, are required to collect and publish hate crime statistics.

Federal prosecution of hate crimes

Civil Rights Act of 1968

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 enacted 18 U.S.C. § 245(b)(2), which permits federal prosecution of anyone who "willingly injures, intimidates or interferes with another person, or attempts to do so, by force because of the other person's race, color, religion or national origin" or because of the victim's attempt to engage in one of six types of federally protected activities, such as attending school, patronizing a public place/facility, applying for employment, acting as a juror in a state court or voting.

Persons violating this law face a fine or imprisonment of up to one year, or both. If bodily injury results or if such acts of intimidation involve the use of firearms, explosives or fire, individuals can receive prison terms of up to 10 years, while crimes involving kidnapping, sexual assault, or murder can be punishable by life in prison or the death penalty.[1] U.S. District Courts provide for criminal sanctions only. The Violence Against Women Act of 1994 contained a provision at 42 U.S.C. § 13981 which allowed victims of gender-motivated hate crimes to seek "compensatory and punitive damages, injunctive and declaratory relief, and such other relief as a court may deem appropriate", but the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Morrison that the provision is unconstitutional.

Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act (1994)

The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, enacted in 28 U.S.C. § 994 note Sec. 280003, requires the United States Sentencing Commission to increase the penalties for hate crimes committed on the basis of the actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, ethnicity, or gender of any person. In 1995, the Sentencing Commission implemented these guidelines, which only apply to federal crimes.[2]

Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act (2009)

On October 28, 2009 President Obama signed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, attached to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010, which expanded existing United States federal hate crime law to apply to crimes motivated by a victim's actual or perceived gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability, and dropped the prerequisite that the victim be engaging in a federally protected activity.

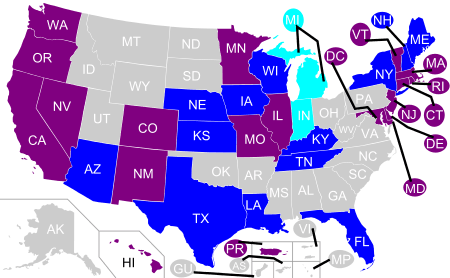

State laws

45 states and the District of Columbia have statutes criminalizing various types of bias-motivated violence or intimidation (the exceptions are Arkansas, Georgia, whose hate crime statute was struck down by the Georgia Supreme Court in 2004,[3] Indiana, South Carolina, and Wyoming). Each of these statutes covers bias on the basis of race, religion, and ethnicity; 32 cover disability; 31 of them cover sexual orientation; 28 cover gender; 17 cover transgender/gender-identity; 13 cover age; 5 cover political affiliation.[4] and 3 along with Washington, D.C. cover homelessness.[5]

31 states and the District of Columbia have statutes creating a civil cause of action, in addition to the criminal penalty, for similar acts.[4]

27 states and the District of Columbia have statutes requiring the state to collect hate crime statistics; 16 of these cover sexual orientation.[4]

3 states and the District of Columbia cover homelessness.[5]

Sexual orientation and gender identity

1983: No LGBT hate crime statute at the state level

1984: California: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[7]

1987: Connecticut: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[8]

1988: Wisconsin: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[9]

1989: Minnesota: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[10]

Nevada: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[11]

Oregon: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[12]

1990: District of Columbia: Sexual orientation and gender identity covered in hate crime statute[13]

New Jersey: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[14]

Vermont: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[15]

1991: Florida: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[16]

Illinois: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[17]

New Hampshire: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[18][19]

1992: Iowa: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[20]

Michigan: Sexual orientation included in hate crime data collection only[21]

1993: Maine: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[22]

Minnesota: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[23]

Washington: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[24]

1996: Massachusetts: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[25]

1997: Delaware: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[26]

Louisiana: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[27]

Nebraska: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[28]

1998: California: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[29]

Rhode Island: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[30]

1999: Missouri: Sexual orientation and gender identity covered in hate crime statute[31]

Vermont: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[15][32]

2000: Indiana: Sexual orientation included in hate crime data collection only[33]

Kentucky: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[34]

New York: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[35][36][37]

Tennessee: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[38]

2001: Texas: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[39]

2002: Kansas: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[40]

Pennsylvania: Sexual orientation and gender identity covered in hate crime statute[41]

Puerto Rico: Sexual orientation and gender identity covered in hate crime statute[42]

2003: Arizona: Sexual orientation covered in hate crime statute[43]

Hawaii: Sexual orientation and gender identity covered in hate crime statute[43]

New Mexico: Sexual orientation and gender identity covered in hate crime statute[43]

2004: Connecticut: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[43]

2005: Colorado: Sexual orientation and gender identity covered in hate crime statute[43]

Maryland: Sexual orientation and gender identity covered in hate crime statute[43]

2008: New Jersey: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[43]

Oregon: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[43]

Pennsylvania: Sexual orientation and gender identity no longer in hate crime statute[44]

2009: Washington: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[43]

2012: Massachusetts: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[45]

Rhode Island: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[46]

2013: Delaware: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[43]

Nevada: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[43]

2016: Illinois: Gender identity covered in hate crime statute[47]

Members of law enforcement

On May 26, 2016, Louisiana was the first state to add police officers and firefighters to their state hate crime statute, when Governor John Bel Edwards signed an amendment from the legislature into law. This amendment was added, in part, as a response to the Black Lives Matter movement, which seeks to end police brutality against black people, with some advocates of the amendment using the slogan "Blue Lives Matter". Since the inception of Black Lives Matter, critics have found some of the movement's rhetoric anti-police, with the author of the amendment, Lance Harris, stating some "were employing a deliberate campaign to terrorize our officers". Despite the killing of a Texas sheriff in 2015 and the killings of two NYPD officers in the previous year, in response to the death of Eric Garner and the shooting of Michael Brown, there was little to no data suggesting hate crimes against law enforcement were a common problem when the bill was passed.[48][49] A little less than two months after the amendment was passed, Baton Rouge was in the national spotlight after the Baton Rouge Police killing of Alton Sterling by two white police officers. This sparked protests in Baton Rouge, resulting in hundreds of arrests and increased racial tension nationally. In the week during those protests, five police officers were killed in Dallas, and the week after the protests, three more officers were killed in Baton Rouge. Both perpetrators were killed and the motives behind both shootings were responses to the recent police killings by police officers of black men.

Data collection statutes

Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990

The Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990 28 U.S.C. § 534, requires the Attorney General to collect data on crimes committed because of the victim's race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, or ethnicity. The bill was signed into law in 1990 by George H. W. Bush, and was the first federal statute to "recognize and name gay, lesbian and bisexual people."[50] Since 1992, the Department of Justice and the FBI have jointly published an annual report on hate crime statistics.[51]

Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994

In 1994, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act expanded the scope to include crimes based on disability, and the FBI began collecting data on disability bias crimes on January 1, 1997.[52] In 1996, Congress permanently reauthorized the Act.

Campus Hate Crimes Right to Know Act of 1997

The Campus Hate Crimes Right to Know Act of 1997 enacted 20 U.S.C. § 1092(f)(1)(F)(ii), which requires campus security authorities to collect and report data on hate crimes committed on the basis of race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or disability. This bill was brought to the forefront by Senator Robert Torricelli.

Prevalence of hate crimes

The DOJ and the FBI have gathered statistics on hate crimes reported to law enforcement since 1992 in accordance with the Hate Crime Statistics Act. The FBI's Criminal Justice Information Services Division has annually published these statistics as part of its Uniform Crime Reporting program. According to these reports, of the over 113,000 hate crimes since 1991, 55% were motivated by racial bias, 17% by religious bias, 14% sexual orientation bias, 14% ethnicity bias, and 1% disability bias.[53]

| Bias Motive | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 6,438 | 6,994 | 6,084 | 5,514 | 5,485 | 5,397 | 5,545 | 4,580 | 4,754 | 5,119 | 4,895 | 5,020 | 4,956 | 4,934 | 3,949 | 3,645 | 3,467 | 3,407 | 3,081 | |

| Religion | 1,617 | 1,535 | 1,586 | 1,720 | 1,686 | 1,699 | 2,118 | 1,659 | 1,489 | 1,586 | 1,405 | 1,750 | 1,628 | 1,732 | 1,552 | 1,480 | 1,340 | 1,163 | 1,014 | |

| Sexual Orientation | 1,347 | 1,281 | 1,401 | 1,488 | 1,558 | 1,558 | 1,664 | 1,513 | 1,479 | 1,482 | 1,213 | 1,472 | 1,512 | 1,706 | 1,528 | 1,572 | 1,376 | 1,402 | 1,017 | |

| Ethnicity/National Origin | 1,044 | 1,207 | 1,132 | 956 | 1,040 | 1,216 | 2,634 | 1,409 | 1,326 | 1,254 | 1,228 | 1,305 | 1,347 | 1,226 | 1,122 | 939 | 866 | 794 | 648 | |

| Disability | unknown | unknown | 12 | 27 | 23 | 36 | 37 | 50 | 43 | 73 | 54 | 95 | 84 | 85 | 48 | 61 | 102 | 92 | 84 | |

| Single-Bias | 10,446 | 11,017 | 10,215 | 9705 | 9,792 | 9,906 | 11,998 | 9,211 | 9,091 | 9,514 | 8,795 | 9,642 | 9,527 | 9,683 | 8,199 | 7,697 | 7,151 | 6,927 | 5,462 | |

| Multiple-Bias | 23 | 22 | 40 | 17 | 10 | 18 | 22 | 11 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 16 | 13 | 6 | 17 | |

| Total | 10,469 | 11,039 | 10,255 | 9,722 | 9,802 | 9,924 | 12,020 | 9,222 | 9,100 | 9,528 | 8,804 | 9,652 | 9,535 | 9,691 | 8,208 | 7,713 | 7,164 | 6,933 | 5,479 |

Notes: The term victim may refer to a person, business, institution, or society as a whole. Though the FBI has collected UCR data since 1992, reports from 1992-1994 are not available on the FBI website. Single-bias victim totals have been calculated for 1995-1998.

| Offense type | Hate Crimes | All US Crimes |

|---|---|---|

| Murder and non-negligent manslaughter | 7 | 16,272 |

| Forcible rape | 11 | 89,000 |

| Robbery | 145 | 441,855 |

| Aggravated assault | 1,025 | 834,885 |

| Burglary | 158 | 2,222,196 |

| Larceny-theft | 224 | 6,588,873 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 26 | 956,846 |

Deliberate attacks on the homeless as hate crimes

Florida, Maine, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. have hate crime laws that include the homeless status of an individual.[5]

A 2007 study found that the number of violent crimes against the homeless is increasing.[56][57] The rate of such documented crimes in 2005 was 30% higher than of those in 1999.[58] 75% of all perpetrators are under the age of 25. Studies and surveys indicate that homeless people have a much higher criminal victimization rate than the non-homeless, but that most incidents never get reported to authorities.

In recent years, largely due to the efforts of the National Coalition for the Homeless (NCH) and academic researchers the problem of violence against the homeless has gained national attention. The NCH called deliberate attacks against the homeless hate crimes in their report Hate, Violence, and Death on Mainstreet USA (they retain the definition of the American Congress).

The Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino in conjunction with the NCH found that 155 homeless people were killed by non-homeless people in "hate killings", while 76 people were killed in all the other traditional hate crime homicide categories such as race and religion, combined.[57] The CSHE contends that negative and degrading portrayals of the homeless contribute to a climate where violence takes place.

Hate crime laws debate

Penalty-enhancement hate crime laws are traditionally justified on the grounds that, in Chief Justice Rehnquist's words, "this conduct is thought to inflict greater individual and societal harm.... bias-motivated crimes are more likely to provoke retaliatory crimes, inflict distinct emotional harms on their victims, and incite community unrest."[59]

Classification of crimes committed against Caucasians

In a 2001 report: Hate crimes on campus: the problem and efforts to confront it, by Stephen Wessler and Margaret Moss of the Center for the Prevention of Hate Violence at the University of Southern Maine, the authors note that "although there are fewer hate crimes directed against Caucasians than against other groups, they do occur and are prosecuted."[60] In fact, the case in which the Supreme Court upheld hate crimes legislation against First Amendment attack, Wisconsin v. Mitchell, 508 U.S. 476 (1993), involved a white victim. Hate crime statistics published in 2002, gathered by the FBI under the auspices of the Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990, documented over 7,000 hate crime incidents, in roughly one-fifth of which the victims were white people.[61] However, these statistics have caused dispute. The FBI's hate crimes statistics for 1993, which similarly reported 20% of all hate crimes to be committed against white people, prompted Jill Tregor, executive director of Intergroup Clearinghouse, to decry it as "an abuse of what the hate crime laws were intended to cover", stating that the white victims of these crimes were employing hate crime laws as a means to further penalize minorities.[62]

James B. Jacobs and Kimberly Potter note that white people, including those who may be sympathetic to the plight of those who are victims of hate crimes by white people, bristle at the notion that hate crimes against whites are somehow inferior to, and less worthy than, hate crimes against other groups. They observe that while, as stated by Altschiller, no hate crime law makes any such distinction, the proposition has been argued by "a number of writers in prominent publications", who have advocated the removal of hate crimes against whites from the category of hate crime, on the grounds that hate crime laws, in their view, are intended to be affirmative action for "protected groups". Jacobs and Potter firmly assert that such a move is "fraught with potential for social conflict and constitutional concerns."

Analysis of the 1999 FBI statistics by John Perazzo in 2001 found that white violence against black people was 28 times more likely (1 in 45 incidents) to be labelled as a hate crime than black violence against white people (1 in 1254 incidents).[63] In analyzing hate crime hoaxes, Katheryn Russell-Brown propounds a hypothesis explaining the disparity in how hate crimes against whites are viewed with respect to hate crimes against blacks. She hypothesizes that the prevailing view in the minds of the public, that hate-crimes-against-blacks hoaxers intend to take advantage of, is that the crime that whites are most likely to commit against blacks is a hate crime, and that it is hard for (in her words) "most of us" to envision a white person committing a crime against a black person for a different reason. The only white people who commit crimes against black people, goes the public belief, are racially prejudiced white extremists. Whereas in contrast, she continues, the situation with hate-crimes-against-whites hoaxers differs, because the popular perception is that black people in general are liable to "run amok, committing depraved, unprovoked acts of violence" against white people.[64]

P. J. Henry and Felicia Pratto assert that while certain hate crimes (that they do not specify) against white people are a valid category, that one can "speak sensibly of", and that while such crimes may be the result of racial prejudice, (and therefore if that is the case, they are squarely covered by hate crime legislation intent for prosecution), in a limited definition of the word, they assert do not constitute actual racism per se, because a hate crime against a member of a group that is superior in the alleged and dated power hierarchy by a member of one that is inferior, they believe may not be racist. The concept of racism as understood by a limited number of social scientists and some others, they allege, requires as a fundamental element a superior-to-inferior group-based power relationship, which a hate crime against white people they believe does not have. However, other social scientists who define racism in a broader sense realize "whites" have over the many centuries, and often do experience discrimination and segregation from their "non white" human cousins, because of their actually or perceived race. And since the components of discrimination and segregation exist within an academic definition of racism, "whites" have been, and many times are victims of racism. Current prison culture in America is a classic example of such discrimination and segregation, as whole groups, and different "races" are discriminated against and segregated based on such, with "whites" receiving more harsh treatment because of their perceived race and/or minority status in prison.

Not all social scientists agree or affirm the opinion/supposition that racism litmus tests should be based on a group-based power relationships that include thousands of individuals over hundreds of years, rather they affirm they should be taken on a more individual case by case basis. Many social scientists agree that this is the most comprehensive and sensible way to determine whether racism is truly a motivating factor when the victim is white and the perpetrator is black. "Whites" are legally protected by hate crimes laws both within the laws themselves, and within the constitution's requirement they receive equal protection of the laws. Therefore, it's a moot point to determine if racism is a factor in the case of "black" on "white" crime for prosecution, since racism alone is not the only factor needed for prosecution. What is relevant to determine prosecution for a hate crime is whether any race or some other "protected characteristic" not "protected groups" was a factor in why a person targeted that/those individual/s to be their victim. e.g. If a "black" person targets a "white" person to be their victim simply because of his/her race or perceived race, whatever their accompanying rationale, they would be subject to hate crime prosecution. However, it's not without merit to determine their rationale, because it's within their rationale that one may verify if a true hate crime has been committed. This is why hate crimes are difficult to prosecute, because they essentially involve prosecuting thoughts rather than physical crimes, which are easier to prove. Evidence does show that in the current culture and climate many black men and women feel superior to whites, and a crime committed by such an individual with said mindset against a white person could clearly have been motivated by racism. Therefore, this individual approach has been preferred over a blanket broad brush approach of past perceived ancestral sufferings and feelings of inferiority and/or superiority of groups that encompass thousands of individuals over hundreds of years.[65]

See also

- Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Civil Rights Act of 1968

- Crime in the United States

- Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2007

References

- ↑ "Civil Rights Statutes".

- ↑ "Hate Crime Sentencing Act". Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ↑ "Nation In Brief". The Washington Post. 2004-10-26. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- 1 2 3 State Hate Crime Laws, Anti-Defamation League, June 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-04;

- 1 2 3 "Florida among first states to make attacks on homeless hate crimes". Retrieved May 25, 2010. May 18, 2010, Orlando Sentinel, Quote: "Florida becomes only the fourth jurisdiction to make attacks on homeless people a hate crime – behind Maryland, Maine and Washington, D.C."

- ↑ Anti-Defamation League, June 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-04;

- ↑ Direct Democracy and Minority Rights: A Critical Assessment of the Tyranny ...

- ↑ United States of America

- ↑ 1987 Wisconsin Act 348

- ↑ Laws of Minnesota 1989

- ↑ ê1989 Statutes of Nevada, Page 898

- ↑ 1989: Oregon hate crime law that includes sexual orientation

- ↑ United States of America

- ↑ Hate Crimes : Criminal Law & Identity Politics: Criminal Law & Identity Politics

- 1 2 Mary Bernsten, "The Contradictions of Gay Ethnicity: Forging Identity in Vermont," in David S. Meyer, et al., eds, Social Movements: Identity, Culture, and the State (Oxford University Press, 2002), 96-7, available online, accessed July 12, 2013

- ↑ Florida Hate Crimes Act, 1991 revisions

- ↑ In re B.C. et al., Minors

- ↑ "HB 1299 - Bill Text". Gencourt.state.nh.us. 1991-01-01. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ↑ "Docket of HB1299". Gencourt.state.nh.us. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ↑ Fair Housing Education

- ↑ Section 28.257a

- ↑ 2011 Maine Revised Statutes TITLE 5: ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURES AND SERVICES Chapter 337-B: CIVIL RIGHTS ACT 5 §4684-A. Civil rights

- ↑ DENNIS HOLLINGSWORTH, et al., Petitioners, v. KRISTIN M. PERRY, et al.

- ↑ United States of America

- ↑ Boston Globe: Doris Sue Wong, "Senate Expands Hate-crime Law," June 21, 1996 accessed March 9, 2011

- ↑ CHAPTER 175

- ↑ "Hate Crimes Bill Out Of Committee With 'Sexual Orientation' Intact," May 1997, Ambush Magazine, Accessed December 23, 2013.

- ↑ NEBRASKA PASSES HATE CRIMES LAW

- ↑ BILL NUMBER : A.B. No. 1999

- ↑ § 12-19-38 Hate Crimes Sentencing Act.

- ↑ Hate crimes--provides enhanced penalties for motivational factors in certain crimes--definitions.

- ↑ Wallace Swan, ed., Handbook of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Administration and Policy (Taylor & Francis, 2005), 131, available online, accessed July 12, 2013

- ↑ HOUSE BILL No. 1011

- ↑ Definitions by various groups, State/federal laws.

- ↑ New York State Assembly: S04691, accessed July 26, 2011

- ↑ New York Times: "Pataki Signs Bill Raising Penalties In Hate Crimes", accessed July 26, 2011

- ↑ Buffalo News: "Last year saw progress on issues of gay rights", accessed July 25, 2011

- ↑ United States of America

- ↑ Texas hate crime law has little effect

- ↑ United States of America

- ↑ "National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Applauds Governor Schweiker for Signing Bill Adding Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity To Existing Classes, December 3, 2002". Pennsylvania Expands Hate Crimes Law. National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ↑ "Puerto Rican activists demand hate-crime charges amid gay, lesbian and transgender slayings". The Miami Herald. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 STATE HATE CRIMES LAWS

- ↑ Jalsevac, John (July 25, 2008). "Pennsylvania Supreme Court Rules that Homosexual 'Hate Crimes' Law Violates Pennsylvania Constitutio". LifeSiteNews. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ↑ Barusch, M.; Reuben, Catherine E. (May 8, 2012). "Transgender Equal Rights In Massachusetts: Likely Broader Than You Think". Boston Bar Journal. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ↑ Rhode Island Hate Crimes Law

- ↑ Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner Signs Enhanced Hate Crimes Law

- ↑ PÉREZ-PEÑA, Richard (27 May 2016). "Louisiana Enacts Hate Crimes Law to Protect a New Group: Police". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Harris, Lance. "HOUSE B I L L NO. 953". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Hate Crimes Protections Timeline, National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Retrieved on 05-04-2007.

- 1 2 "Uniform Crime Reports". CJIS. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ↑ "Hate crime statistics 1996" (PDF). CJIS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-09. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ↑ Abrams, J. House Passes Extended Hate Crimes Bill, Guardian Unlimited, 05-03-2007. Retrieved on 05-03-2007.

- ↑ "Table 2 - Hate Crime Statistics 2008". CJIS. Archived from the original on 2013-05-14. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ↑ "Table 1 - Crime in the United States 2008". CJIS. Archived from the original on 2009-09-22. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ↑ Lewan, Todd, "Unprovoked Beatings of Homeless Soaring", Associated Press, April 8, 2007.

- 1 2 National Coalition for the Homeless, Hate, "Violence, and Death on Main Street USA: A report on Hate Crimes and Violence Against People Experiencing Homelessness, 2006", February 2007.

- ↑ National Coalition for the Homeless: A Dream Denied.

- ↑ Wisconsin v. Mitchell, 508 U.S. 476 (1993).

- ↑ Donald Altschiller (2005). Hate crimes: a reference handbook. Contemporary world issues (2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 146. ISBN 9781851096244.

- ↑ Joel Samaha (2005). Criminal justice (7th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 44. ISBN 9780534645571.

- ↑ Jacobs, James B.; Potter, Kimberly (2000). Hate crimes: criminal law & identity politics. Studies in Crime and Public Policy. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 134. ISBN 9780198032229.

When the FBI's 1993 hate crime statistics reported that whites comprised 20 percent of all hate crime victims, some advocacy groups questioned whether the hate crime laws were being perverted.12 Jill Tregor, executive director of the San Francisco-based Intergroup Clearinghouse, which provides legal and emotional counseling to hate crime victims, stated, "This is an abuse of what the hate crime laws were intended to cover."13 Tregor accused white hate crime victims of using the laws to enhance penalties against minorities, who already experience prejudice within the criminal justice system.14 Whites, generally sympathetic to the aspirations of minorities, may bristle at the suggestion that crimes motivated by blacks' racism against whites should be treated as a less virulent strain of hate crime, or not as hate crime at all. While no enacted hate crime law makes that distinction, a number of writers in prominent publications, likening hate crime laws to affirmative action for "protected groups," advocate the exclusion of racist crimes against whites from their coverage.15 This issue alone seems fraught with potential for social conflict and constitutional concerns.

- ↑ Anthony Walsh (2004). Race and crime: a biosocial analysis. Nova Publishers. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9781590339701.

- ↑ Katheryn Russell-Brown (1998). The color of crime: racial hoaxes, white fear, black protectionism, police harassment, and other macroaggressions. Critical America. NYU Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780814774717.

- ↑ P. J. Henry and Felicia Pratto (2010). "Power and Racism". In Ana Guinote and Theresa K. Vescio. The Social Psychology of Power. Guilford Press. p. 344. ISBN 9781606236192.

External links

- Database of hate crime statutes by state, via Anti-Defamation League

- [Hate Crimes Bill S. 1105], detailed information on hate crimes bill.

- "Hate Crime." Oxford Bibliographies Online: Criminology.