Hasan al-Askari

| Hasan al-Askari الحسن العسكري (Arabic) = 11th Imam of Twelver Shia Islam | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

c. 6 December 846 CE[1] (8 Rabi al-thani 232 AH) Medina, Abbasid Empire |

| Died |

c. 4 January 874 (aged 27)[1] (8 Rabi al-awwal 260 AH) Samarra, Abbasid Empire |

| Cause of death | Death by poisoning according to most Shi'a Muslims |

| Resting place |

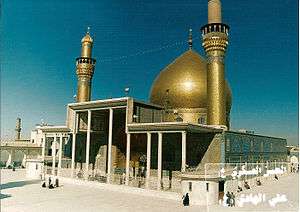

Al-Askari Mosque, Iraq 34°11′54.5″N 43°52′25″E / 34.198472°N 43.87361°E |

| Other names | Hasan ibn Ali ibn Muhammad |

| Title | |

| Term | 868 – 874 CE |

| Predecessor | Ali al-Hadi |

| Successor | Muhammad al-Mahdi |

| Religion | Islam |

| Spouse(s) | Narjis |

| Children | Muhammad al-Mahdi |

| Parent(s) |

Ali al-Hadi Saleel[3]a |

| Relatives |

Muhammad (brother) Ja'far (brother) |

| Notes | |

Hasan ibn Ali ibn Muhammad (c. 846 – 874) was the 11th Imam of Twelver Shia Islam, after his father Ali al-Hadi. He was also called Abu Muhammad and Ibn al-Ridha. Because Samarra, the city where he lived, was a garrison town, he is generally known as al-Askari (Askar is the word for military in Arabic). Al-Askari married Narjis Khatun and was kept in house arrest or prison for most of his life until, according to some Shia sources, he was poisoned at the age of 28 on the orders of the Abbasid caliph Al-Mu'tamid and was buried in Samarra. It was known that many Shia were looking forward the succession of his son, Muhammad al-Mahdi, as they believed him to be the twelfth Imam, who was destined to remove injustice from the world.[5][6][7][8][9]

Athnā‘ashariyyah Shi‘ah |

|---|

Birth and early life

Hasan al-Askari was born during a period when his father Ali al-Hadi, the tenth Imam, was suspected of being involved in a conspiracy against the Caliph Al-Mutawakkil. There is doubt as to whether al-Askari was born in Medina or Samarra. According to authentic shia hadith he was born in Medina on the 10th of Rabuil Akhar 232 Hijri (6.12.846 AD) and died in Samarrah Iraq on 8th of Rabiul Awwal 260 Hijri (4.1.874) aged 28. Period of imamate was 6 years. He was taken along with his family to Samarra in the year 230, 231 or 232 A.H., and was kept there under house arrest. In Samarra, al-Askari spent most of his time perusing the Quran and the Sharia. According to Donaldson, al-Askari must also have studied languages, for in later years it was known that he could speak Hindi with the pilgrims from India, Turkish with the Turks, and Persian with the Persians.[10] According to Shia accounts, however, it is part of the divine knowledge given to all Imams to be able to speak all human languages.[11][12]

It is said that even as a child, al-Askari was bestowed with divine knowledge. One day a man passed by him, and saw that he was crying. The man told him he would buy a toy that he might play with. "No!" said al-Askari, "We have not been created for play." The man was amazed at this answer and said, "Then, what for have we been created?" "For knowledge and worship." answered the child. The man said "Where have you got this from?" Al-Askari said, "From the saying of God, Did you then think that We had created you in vain."[lower-alpha 1] The man was confused, so he said, "What has happened to you while you are guiltless, little child?" al-Askari said, "Be away from me! I have seen my mother set fire to big pieces of firewood, but fire is not lit except with small pieces, and I fear that I shall be from the small pieces of the firewood of the Hell."[13][14]

Al-Askari's mother, as in the case of the majority of The Twelve Imams, was a slave girl who was honoured after bearing children with the title Umm walad (mother of offspring). Her own name was Hadith, though some say she was called Susan, Ghazala, Salil, or Haribta.[10] Al-Askari had other brothers, and among them was Ja’far who was also known as Ja'far al-Zaki or Jaffar-us-Sani. His other brother was Husayn, and together he and al-Askari were known as "as-Sibtayn", after their two grandfathers Hasan and Husayn, who were also called as-Sibtayn.[15]

His wife

Various legends relate to al-Askari's wife, Narjis Khatun (the mother of the twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi). It is said that al-Askari's father, Ali al-Hadi, wrote a letter in the script of Rum and put it in a red purse, with 220 Dinars, and gave it to his friend Bashar ibn Sulaiman. The letter instructed him to go to Baghdad, to a ferry at the river where the boats from Syria were unloaded, and female slaves were sold. Bashar was told to look out for a ship-owner named Amr ibn Yazid, who had a slave girl who would call out in the language of Rum: "Even if you have wealth and the glory of Solomon the son of David, I can never have affection for you, so take care lest you waste your money." And that if a buyer approached her, she would say "Cursed be the man who unveils my eyebrow!" Her owner would then protest, "But what recourse do I have I; I am compelled to sell you?" "You will then hear the slave answer", said the Imam, "Why this hast, let me choose my purchaser, that my heart may accept him in confidence and gratitude."

Bashar gave the letter, as he was instructed, to the slave girl; who read it, and was not able to keep from crying afterward. Then she said to Amr ibn Yezid, "Sell me to the writer of this letter, for if you refuse I will surely kill myself." "I therefore talked over the price with Amr until we agreed on the 220 Dinars my master had given me," said Bashar. On her way to Samarra, the slave girl would kiss the letter and rub it to her face and body; and when asked by Bashar why she did so despite not knowing the writer of the letter, she said, "May the offspring of the Prophet dispel your doubts!" Later on, however, she gave a full description of the dream she had had, and how she had escaped from her father's palace. This lengthier story is recorded in Donaldson's book, along with further discussion on the authenticity of this story.[10]

Some Shia sources have recorded her as being a "Roman (i.e. Byzantine) princess" who pretended to be a slave so that she might travel from her kingdom to Arabia.[16][17][18] Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, in the Encyclopedia of Iranica, suggests that the last version is "undoubtedly legendary and hagiographic".[6][18]

Imamate

Athnā‘ashariyyah Shi‘ah |

|---|

Shia believe that Hasan al-Askari gained the Imamate after the death of his father through Divine Command, as well as through the decree of the previous Imams, at the age of 22. During the seven years of his Imamate, Hasan al-Askari lived in dissimulation (taqiyah), without any social contact, as the Abbasid Caliphs were afraid of Shia due to increasingly popularity at the time. The Caliphs also came to know that the leaders among the Shia believed that the eleventh Imam would have a son who was the promised Mahdi.[lower-alpha 2] Due to these fears, the Caliphs of the time had decided definitely to put an end to the Imamate in Shiism once and for all.[5]

Under the rule of the Abbasid Caliphs

Hasan al-Askari lived almost his entire life under house arrest in Samarra and under supervision of Abbasid caliphs.[19] He criticized the rulers for appropriating the wealth of the nation and extorting the people under their rule by not communicating with or cooperating with the kings of his time. The state remained in a political crisis, as the Abbasid Caliphs were considered puppets of the Turks, who were seen as ruling through terrorism. After the death of al-Askari's father, Ali al-Hadi, the Caliph Al-Mu'tazz summoned him to Baghdad, where he was kept in prison during the short rule of the next Caliph, Al-Muhtadi. Most of his prison experiences, however, were at the time of the succeeding Caliph Al-Mu'tamid, who is known in Shia sources as the main oppressor of the Imam.[10] The cause of the Imam's death has largely been speculated to be due to poison administered by al-Mu'tamid.[20]

Divisions

There was a large sect of the Shia, the waqifiyya, who believed that the Imamate stopped with Ali al-Ridha, and they were unwilling to approve the succession of the remaining Imams. That is why al-Askari, his father, Ali al-Hadi, and his grandfather, Muhammad al-Jawad, were called at times "Ibn Ridha" (the son of al-Ridha), to show that this succession continued through al-Ridha's descendants. Ja’far, the son of the tenth Imam, claimed to be Imam after the death of his brother, al-Askari, and was followed by a group of Shia. However, this group scatter soon afterwards, as Ja’far himself gave up his claim. Except the Zaidiyyah and the Isma'ilism, which continue to exist until the present day, all other minority sects of Twelver Shia were dissolved in a short period.[5]

Expertise

During their lifetimes, the Shia Imams trained hundreds of scholars whose names and works can be found in biographical books.[lower-alpha 3][5] During the time of the Eleventh Imam, however, some Shia saw Islamic religious life as being in shambles. The Imam was under house arrest and many non-believers took advantage of this to question religion, in spite of his continuing to speak out against those who questioned the Qur'an. The account of this could be found in a Tafsir ascribed to him. This can also be seen when a philosopher by the name of Al-Kindi, who is considered as the first Muslim Philosopher, wrote a book entitled "The Contradiction of the Quran". The news came to al-Askari, who met one of al-Kindi's disciples and said to him, "Is there no wise man among you to prevent your teacher, al-Kindi, from that which he has busied himself with?"

The disciple answered that they were al-Kindi's disciples and were not able to object. Later on Hasan al-Askari instructed the disciple how to question al-Kindi.

"Go to him, be courteous with him, and show him that you will help him in what he is in. When he feels comfortable with you, you say to him, 'If someone recites the Quran, is it possible that he means other meanings than what you think you understand? He shall say that it is possible because he is a man who understands when he listens. If he says that, you say to him, How do you know? He might mean other than the meanings that you think, and so he fabricates other than its (the Qur'an) meanings…".[21]

The disciple did as al-Askari advised him; and Al-Kindi was shrewd enough to say, "...no one like you can get to this. Would you tell me where you have got this from?" And when he heard the true story said "Now you say the truth. Like this would not come out except from that house (the Ahlul Bayt)…". It is said that al-Kindi burnt his book afterwards.[21][22]

Tafsir al-Askari

Despite being confined to house arrest for almost his entire life, Hasan al-Askari was able to teach others about Islam, and even compiled a commentary on the Quran that became known as Tafsir al-Askari. However, there was much suspicion regarding whether it truly was his or not. The Tafsir was accused by some to be weak in its chain of authorities (Sanad), which is an essential part of the transmission of a tradition.[23] The Tafsir was also questioned because it contained a few inconsistencies and lacks eloquence, which some claim ruin its validity by default. The main reason people questioned the validity of the Tafsir was the fact that the Imam was under constant watch by the Abbasid government, who prevented any contact between him and the Shia so that it would be impossible for such knowledge to be transferred.[24]

Selected sayings

- "If anyone of you is pious in his religion, truthful in his speech, gives deposit back to its owner, and treats people kindly, it shall be said about him: ―this is a Shiite."[25]

- "Do not hasten towards a fruit that is not ripe yet for it has its time! …Trust in His (God's) experience in your affairs and do not hurry for your needs at the beginning of your time that your heart may be distressed and despair may overcome you!"[25]

- "Worship is not abundant fasting and praying, rather worship is abundant pondering; it is the continuous thinking of God."[25]

- "Anger is the key to every evil."[25]

- "A spiteful one is the least comfortable."[25]

- "There are two qualities that no quality is over; the faith in God and the serving of brothers."[25]

- "Humbleness is a blessing that is not envied."[25]

- "Had all people of this world been intelligent, the world would have been ruined.[25] (Because they only spend their life for the Day of Judgement.)[26][27]

- "The weakest of enemies in cunning, is he who shows his enmity."[25]

- "Vices have been put in a house whose key is lies."[25]

Death

Hasan al-Askari, according to some Shia sources, was poisoned at the age of 28 through the instigation of the Abbasid caliph Al-Mu'tamid and died on the 8th Rabi' al-Awwal 260 AH (approximately: 4 January 874)[28] in his own house in Samarra. He was buried in the same place with his father.[6]

As soon as the news of the illness of the eleventh Imam had reached al-Mu'tamid, he sent a physician and a group of his trusted men to his house to observe his condition. After the death of the Imam, they had all his female slaves examined by the midwives. For two years, they searched for the successor of the Imam until they eventually lost hope. Al-Askari died on the very same day that his young son, Muhammad al-Mahdi, who then was five or a little over, disappeared and started what was henceforth known as the Minor Occultation.[5][10]

His Son, the Promised Mahdi

Shias believe that al-Askari had a son whose birth, like the case of the prophet Moses, was concealed due to the difficulties of the time and because of the belief that he was the promised Muhammad al-Mahdi, an important figure in Shia teachings. This figure was believed to be destined to reappear before the end of time to fill the world with justice, peace and to establish Islam as the global religion. It is said that when his uncle, who became known as "Ja'far the liar" or the "false Ja'far," was about to say the prayer at Hasan al-Askari's funeral, "a fair child, with curly hair, and shining teeth" appeared and seized his uncle's cloak insisting that he himself should say the prayer. Later, when a few days had passed, a group of Shia pilgrims came from Qum to visit al-Askari, who was dead. The same Ja'far claimed to be the next Imam. The pilgrims said they would accept him if he would prove himself by telling them their names and indicating how much money they had. While Ja'far was protesting against this examination, a servant of al-Mahdi appeared, saying that his master had sent him to inform them of their particular names and their specific amounts of money. Ja'far searched everywhere but could not find the boy, al-Mahdi. The doctrine of his ghaiba declares simply that the Mahdi has been "withdrawn by God from the eyes of men, that his life has been miraculously prolonged, that he has been seen from time to time and has been in correspondence with others, and maintains a control over the fortunes of his people."[10]

See also

- Ali al-Hadi

- Muhammad al-Mahdi

- Sayyid Ali Akbar

- List of extinct Shia sects

- Muhammad ibn Ali al-Hadi

- Muhammadite Shia

- Imamate (Twelver doctrine)

- Ahl Al-Bayt

Notes

- ↑ Quran, 23:115

- ↑ The coming of the Mahdi had been foretold by both Shia and Sunni traditions. See Sahih of Tirmidhi. Cairo, 1350-52. vol. IX, chapter "Ma ja a fi’l-huda": Sahih of Abu Da’ud, vol.ll, Kitab al-Mahdi: Sahih oflbn Majah, vol.ll. chapter khurui’ al-Mahdi": Yanabi’ al-mawaddah: Kitab al-bayan fi akhbar Sahib al zaman of Kanji Shaafi’i, Najaf, 1380; Nur al-absar: Mishkat almasabih of Muham. mad ibn ’Abdallan al-Khatib. Damascus, 1380; al- Sawa’iq al-muhriqah, Is’af al raghibin of Muhammad al-Sabban, Cairo. 1281: al-Fusul al-muhimmmah; Sahih of Muslim: Kitab al-ghaybah by Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Nu’mani, Tehran, 1318; Kamal al-din by Shaykh Saduq. Tehran, 1301; lthbat al-hudat; Bihar al-anwar, vol. LI and LII.

- ↑ See Kitab al-rijal of Kashshi; Rijal of Tusi; Fihrist of Tusi, and other works of biography (rijal).[5]

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Shareef al-Qurashi 2005

- 1 2 Shareef al-Qurashi 2005, pp. 16–18

- ↑ "The Imam's Noble Lineage | The Life of Imam Hasan Al-'Askari | Books on Islam and Muslims". Al-Islam.org. 1999-02-22. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ↑ "Imam Hassan Askari (As)". Ziaraat.org. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tabataba'i, Muhammad Husayn (1979). Shi'ite Islam. State University of New York Press. pp. 184–185 & 69.

- 1 2 3 Tabåatabåa'åi, Muhammad Husayn (1981). A Shi'ite Anthology. Selected and with a Foreword by Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i; Translated with Explanatory Notes by William Chittick; Under the Direction of and with an Introduction by Hossein Nasr. State University of New York Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780585078182.

- ↑ Corbin, Henry (2001). The History of Islamic Philosophy. Translated by Liadain Sherrard with the assistance of Philip Sherrard. London and New York: Kegan Paul International. pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Shareef al-Qurashi 2005, p. 18

- ↑ Eliash, J. "Ḥasan al- ʿAskarī , Abū Muḥammad Ḥasan b. ʿAlī." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2010. Brill Online. Augustana. 13 April 2010 <http://www.brillonline.nl/subscriber/entry?entry=islam_SIM-2762>

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi'ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Irak. BURLEIGH PRESS. pp. 217–222.

- ↑ Al-Qurashi, Baqir Shareef. The Life of Imam ‘Ali al-Hadi, Study and Analysis. Abdullah al-Shahin. Qum: Ansariyan Publications. p. 82. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Koleini, Mohammad (1362). Osule Kafi. 1. Tehran: Islamie. pp. 509 & 285.

- ↑ Shareef al-Qurashi 2005, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Shoushtari, Noorollah. Ihqaq-al-Haq. 12. p. 473.

- ↑ Shareef al-Qurashi 2005, p. 23

- ↑ The Expected Mahdi

- ↑ "Online Islamic Courses". Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- 1 2 Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali. "ISLAM IN IRAN vii. THE CONCEPT OF MAHDI IN TWELVER SHIʿISM". Encyclopedia iranica. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- ↑ Meri, Josef W. (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. USA: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96690-0.

- ↑ Shareef al-Qurashi 2005, p. 188

- 1 2 Shareef al-Qurashi 2005, pp. 162–163

- ↑ Shahr Ashoub, Abu Abdullah Ali. Manaqib e Ale Abi Talib. 4. p. 424.

- ↑ Robson, J. "Isnād." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2010. Brill Online. Augustana. 13 April 2010 <http://www.brillonline.nl/subscriber/entry?entry=islam_SIM-3665>

- ↑ Shareef al-Qurashi 2005, pp. 80–86

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Shareef al-Qurashi 2005, pp. 68–75

- ↑ "Library of Shia Ahadith".

- ↑ Mohammadi Rey Shahri, Mohammad. Mizan al Hikmat. 5.

- ↑ Mufīd, Ibn-al-Muʻallim, I. K. A. Howard, and Ḥusain Naṣr. Kitāb Al-Irshād: the Book of Guidance into the Lives of the Twelve Imams. Qum: Ansariyan Publications, 1990. Print.

References

- Shareef al-Qurashi, Baqir (2005). The Life of Imam Al-Hasan Al-Askari. Translation by: Abdullah al-Shahin. Ansariyan Publications – Qum.

External links

- The Life of Imam Al-Hasan Al-Askari

- Roshd foundation

- ABU MOHAMMAD HASAN B. ALI ASKARI by H. Halm, An article of Encyclopædia Iranica

- The Eleventh Imam

- Hasan Askari

| Shia Islam titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ali al-Hadi |

11th Imam of Twelver Shia Islam 868 – 874 |

Succeeded by Muhammad al-Mahdi |