Hamitic

Hamitic (from the biblical Ham) is a historical term in ethnology and linguistics for a division of the Caucasian race and the group of related languages these populations spoke. The appellation Hamitic was applied to the Berber, Cushitic and Egyptian branches of the Afroasiatic family, which, together with the Semitic branch, was thus formerly labelled "Hamito-Semitic".[1] However, since the three Hamitic branches have not been shown to form an exclusive (monophyletic) phylogenetic unit of their own, separate from other Afroasiatic languages, linguists no longer use the term in this sense. Each of these branches is instead now regarded as an independent subgroup of the larger Afroasiatic family.[2]

Beginning in the 19th century, scholars generally classified the Hamitic race as a subgroup of the Caucasian race, along with the Semitic race – thus grouping the non-Semitic populations native to North Africa and the Horn of Africa, including the Ancient Egyptians.[3] According to the Hamitic theory, this "Hamitic race" was superior to or more advanced than Negroid populations of Sub-Saharan Africa. In its most extreme form, in the writings of C. G. Seligman, this theory asserted that virtually all significant achievements in African history were the work of "Hamites" who had migrated into central Africa as pastoralists, bringing new customs, languages, technologies and administrative skills with them. In the early 20th century, theoretical models of Hamitic languages and of Hamitic races were intertwined.[4]

This nomenclature gradually fell out of favour between the 1960s and 1980s, in large part due to its perceived association with colonial paternalism. The populations of Hamitic ancestral stock are now more commonly known as "Caucasoid".[5]

Hamitic race

Concept of the Curse of Ham

The term Hamitic originally referred to the peoples said to be descended from Ham, one of the Sons of Noah according to the Bible. According to the Book of Genesis, after Noah became drunk and Ham dishonored his father, upon awakening Noah pronounced a curse on Ham's youngest son, Canaan, stating that his offspring would be the "servants of servants". Of Ham's four sons, Canaan fathered the Canaanites, while Mizraim fathered the Egyptians, Cush the Cushites, and Phut the Libyans.[6]

During the Middle Ages, believing Jews, Christians, and Muslims incorrectly considered Ham to be the ancestor of all Africans. Noah's curse on Canaan as described in Genesis began to be misinterpreted by some scholars in Europe as having caused visible racial characteristics in all of Ham's offspring, notably black skin. According to Edith Sanders, the sixth-century Babylonian Talmud says that "the descendants of Ham are cursed by being Black and [it] depicts Ham as a sinful man and his progeny as degenerates."[7] Some Arab slave traders used the account of Noah and Ham in the Bible to justify Negro (Zanj) slavery, and later European and American Christian traders and slave owners adopted a similar argument.[7][8]

However, the Bible itself indicates that Noah restricted his curse to the offspring of Ham's youngest son Canaan, whose descendants occupied the Levant, and it was not extended to Ham's other sons, who had migrated into Africa. According to Sanders, 18th-century theologians increasingly emphasized this narrow restriction and accurate interpretation of the passage as applying to Canaan's offspring. They rejected the curse as a justification for slavery.[7]

Hamitic hypothesis

Many versions of this perspective on African history have been proposed, and applied to different parts of the continent. The essays below focus on the development of these ideas regarding the peoples of North Africa, the Horn of Africa and the African Great Lakes. However, Hamitic hypotheses operated in West Africa as well, and they changed greatly over time.[9]

In the mid-19th century, the term Hamitic acquired a new meaning as scholars asserted that they could anthropologically discern a "Hamitic race" that was distinct from the "Negroid" populations of Sub-Saharan Africa. The theory arose from early anthropological writers, who linked the stories in the Bible of Noah's sons to documented ancient migrations of peoples from the Middle East into Africa.[7] The theory that this group had migrated further south was popularized by the British explorer John Hanning Speke, in his publications on his search for the source of the Nile River.[7] Speke believed that his explorations uncovered the link between "civilized" North Africa and "primitive" central Africa. Describing the Ugandan Kingdom of Buganda, he argued that its "barbaric civilization" had arisen from a nomadic pastoralist race who had migrated from the north and was related to the Hamitic Oromo (Galla) of Ethiopia.[7] In his Theory of Conquest of Inferior by Superior Races (1863), Speke would also attempt to outline how the Empire of Kitara in the African Great Lakes region may have been established by a Hamitic founding dynasty.[10]

These ideas, under the rubric of science, provided the basis for some Europeans asserting that the Tutsi were superior to the Hutu. In spite of both groups being Bantu-speaking, Speke thought that the Tutsi had experienced some "Hamitic" influence, partly based on their facial features being comparatively more narrow than those of the Hutu. Later writers followed Speke in arguing that the Tutsis had originally migrated into the lacustrine region as pastoralists and had established themselves as the dominant group, having lost their language as they assimilated to Bantu culture.[11]

In his influential The Mediterranean Race (1901), the anthropologist Giuseppe Sergi argued that the Mediterranean race had likely originated from a common ancestral stock that evolved in the Sahara region in Africa, and which later spread from there to populate North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and the circum-Mediterranean region.[12] According to Sergi, the Hamites themselves constituted a Mediterranean variety, and one situated close to the cradle of the stock.[13] He added that the Mediterranean race "in its external characters is a brown human variety, neither white nor negroid, but pure in its elements, that is to say not a product of the mixture of Whites with Negroes or negroid peoples."[14] Sergi explained this taxonomy as inspired by an understanding of "the morphology of the skull as revealing those internal physical characters of human stocks which remain constant through long ages and at far remote spots[...] As a zoologist can recognise the character of an animal species or variety belonging to any region of the globe or any period of time, so also should an anthropologist if he follows the same method of investigating the morphological characters of the skull[...] This method has guided me in my investigations into the present problem and has given me unexpected results which were often afterwards confirmed by archaeology or history."[15]

The Hamitic hypothesis reached its apogee in the work of C. G. Seligman, who argued in his book The Races of Africa (1930) that:

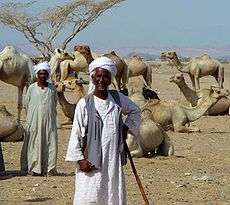

Apart from relatively late Semitic influence... the civilizations of Africa are the civilizations of the Hamites, its history is the record of these peoples and of their interaction with the two other African stocks, the Negro and the Bushmen, whether this influence was exerted by highly civilized Egyptians or by such wider pastoralists as are represented at the present day by the Beja and Somali... The incoming Hamites were pastoral 'Europeans' – arriving wave after wave – better armed as well as quicker witted than the dark agricultural Negroes."[7][16]

Seligman asserted that the Negro race was essentially static and agricultural, and that the wandering Hamitic "pastoral Caucasians" had introduced most of the advanced features found in central African cultures, including metal working, irrigation and complex social structures.[7][17] Despite criticism, Seligman kept his thesis unchanged in new editions of his book into the 1960s.

Hamitic types

In the 19th century Meyers Konversations-Lexikon (1885–90), Hamitic was a subdivision of the Caucasian race alongside Aryan (Indo-European) and Semitic (Semitic languages).[18] Sergi outlined the constituent Hamitic physical types, which would form the basis for the work of later scholars. In his book The Mediterranean Race (1901), he asserted that there was a distinct Hamitic ancestral stock, which could be divided into two subgroups: the Western Hamites (or Northern Hamites), and the Eastern Hamites (or Ethiopids).[19]

According to Ashley Montagu, "among both the Northern and Eastern Hamites are to be found some of the most beautiful types of humanity".[3] Typical Hamitic physical traits included narrow facial features; an orthognathous visage; light brown to dark brown skin tone; wavy, curly or straight hair; thick to thin lips without eversion; and a dolichocephalic to mesocephalic cranial index. These somatic attributes varied depending on the environment and through contact with non-Hamitic stocks. Among the Western Hamites, Semitic and Negroid influences could be found in urban areas, with a Nordic strain present in the northwestern mountains. Similar non-Hamitic elements also existed among the Eastern Hamites, but with a more marked Negroid influence in areas bordering the Upper Nile and Great Lakes and a pronounced Armenoid strain in the Eastern Desert.[20]

Although the particulars of the Eastern Hamitic and Western Hamitic groupings varied, they were generally as follows:[4]

- Western Hamites

- Berbers – Hamitic autochthones of the Maghreb and parts of the Nile Valley. Descended from the Meshwesh, Tehenu and other Ancient Libyan tribes.[20]

- Guanches – Berber-speaking natives of the Canary Islands. Although now extinct, left behind a number of descendants on the archipelago.[20]

- Maghrebis – Berber indigenes of the non-rural Maghreb. Descended from the Ancient Libyan tribes, but adopted Arabian genealogies and the Arabic language with the spread of Islam during the Middle Ages.[20]

- Moors – Arabic-speaking Berber natives of the Western Sahara.[20]

- Tuareg – Technically a Berber population of the Sahara. However, distinguished by a more pronounced dolichocephaly and greater height. Only Berber group to preserve the ancient Libyco-Berber writing script, known today as Tifinagh.[20]

- Eastern Hamites

- Abyssinians – Hamitic inhabitants of the Ethiopian and Eritrean highlands. Essentially Semiticized Agaws.[4]

- Afar – Cushitic-speaking Hamitic population of the Horn region. Also known as the Danakil.[4]

- Agaw – Root Hamitic stock of northern and central Ethiopia. Speak the original Cushitic languages of the Abyssinians.[4]

- Beja – Cushitic-speaking Hamitic confederation inhabiting Eritrea, Sudan and Egypt. An ancient population, they are attested on temple murals as early as the Twelfth Dynasty.[21]

- Egyptians – Descendants of the Hamitic ancient Egyptians. This pharaonic heritage is most salient among the Copts and Fellahin, with the Coptic language representing a variety of the old Egyptian language.[20]

- Oromo – Hamitic inhabitants of Ethiopia and environs. Also known as the Galla, they are believed to have introduced many cultural and lexical elements to communities in the Great Lakes region to the south.[4]

- Nubians – Descendants of the Hamitic populations of ancient Nubia, such as the makers of the A-Group, C-Group and Kerma cultures. In later times, they adopted the Nilo-Saharan (Nobiin) lingua franca of the local Sudanese market towns.[21]

- Somalis – Hamitic inhabitants of the Horn. Descended from the Cushitic-speaking natives of the ancient Barbara region.[4]

In the Sahara, on the margins of the Hamitic nucleus in the northwest and northeast, several populations speaking non-Hamitic languages yet possessing some Hamitic physical affinities could be found. Among these were the Fulani, who were believed to have been of Berber origin. Beginning in the late medieval period, as they assimilated into the burgeoning states of the Western Sudan, the Fulani are thought to have gradually adopted the Niger-Congo tongue of their urban neighbors. As a result, the Hamitic element was most marked among the Bororo and other pastoral Fulani groups rather than in the Fulanin Gidda settled communities. Similarly, the Toubou of the Tibesti Mountains were held to have descended from the ancient Garamantes. This Hamitic ancestry was believed to be most salient among the northern Teda Toubou, as the southern Daza Toubou often intermarried with the adjacent Nilotic populations.[20][21]

Hamiticised Negroes

Seligman and other early scholars believed that, in the African Great Lakes and parts of Central Africa, invading Hamites from North Africa and the Horn of Africa had mixed with local Negro women to produce several hybrid "Hamiticised Negro" populations. The Hamiticised Negroes were divided into three groups according to language and degree of Hamitic influence: the Negro-Hamites or Half-Hamites (such as the Maasai, Nandi and Turkana), the Nilotes (such as the Shilluk and Nuer), and the Bantus (such as the Hima and Tutsi). Seligman would explain this Hamitic influence through both demic diffusion and cultural transmission:[4]

At first the Hamites, or at least their aristocracy, would endeavour to marry Hamitic women, but it cannot have been long before a series of peoples combining Negro and Hamitic blood arose; these, superior to the pure Negro, would be regarded as inferior to the next incoming wave of Hamites and be pushed further inland to play the part of an incoming aristocracy vis-a-vis the Negroes on whom they impinged... The end result of one series of such combinations is to be seen in the Masai [sic], the other in the Baganda, while an even more striking result is offered by the symbiosis of the Bahima of Ankole and the Bahiru [sic].[17]

In the African Great Lakes region, European scholars based the various migration theories of Hamitic provenance in part on the long-held oral traditions of local populations such as the Tutsi and Hima (Bahima, Wahuma or Mhuma). These groups asserted that their founders were "white" migrants from the north (interpreted as the Horn of Africa and/or North Africa), who subsequently "lost" their original language, culture, and much of their physiognomy as they intermarried with the local Bantus. The British explorer John Hanning Speke recorded one such account from a Wahuma governor in his book, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile.[22] According to Augustus Henry Keane, the Hima King Mutesa I also claimed Oromo (Galla) ancestors and still reportedly spoke an Oromo idiom, though such Hamitic-Semitic language had long since died out elsewhere in the region.[23] The missionary R. W. Felkin, who had met the ruler, remarked that Mutesa "had lost the pure Mhuma features through admixture of Negro blood, but still retained sufficient characteristics of that tribe to prevent all doubt as to his origin".[24] Thus, Keane would suggest that the original Hamitic migrants to the Great Lakes had "gradually blended with the aborigines in a new and superior nationality of Bantu speech".[23]

While some scholars accepted the idea of Sub-Saharan tribes such as the Tutsi and the Maasai being Hamiticised Negroes, others, such as John Walter Gregory, emphasized that the putative Hamitic element in these peoples was at best minimal. Citing the considerable physical disparity between the ethnic groups traditionally considered Hamites and the aforementioned "Hamiticised Negroes", Gregory wrote:

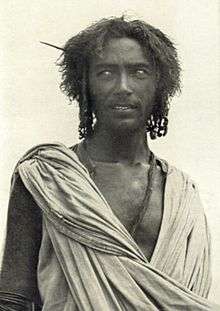

By some authorities the Masai are included in the Hamitic group, but we have only to compare the features of a member of this tribe with those of a Galla... to realise the predominance of the negro element in the former. The aspect of the pure Hamite differs altogether from those of the Bantu and Negroid races. The... portrait of a Galla presents no correspondence with the conception usually formed of an African native. The forehead is high and square instead of low and receding; the nose is narrow, with the nostrils straight and not transverse; the chin is small and slightly pointed instead of massive and protruding; the hair is long and not woolly; the lips are thinner than those of the negro and not everted; the expression is intellectual, and indicates a type of mind higher than that of the simple negro. Indeed, except for the colour, it could hardly be distinguished from the face of a European. These characteristics prepare us for the fact that the Galla are not African, but immigrants from Asia.[25]

European imperial powers were influenced by the Hamitic hypothesis in their policies during the twentieth century. For instance, in Rwanda, German and Belgian officials in the colonial period displayed preferential attitudes toward the Tutsis over the Hutu. Some scholars argued that this bias was a significant factor that contributed to the 1994 Rwandan genocide of the Tutsis by the Hutus.[26][27]

African-American views

African-American scholars were initially ambivalent about the Hamitic hypothesis. Because Sergi's theory proposed that the superior Mediterranean race had originated in Africa, some African-American writers believed that they could appropriate the Hamitic hypothesis to challenge claims about the superiority of white Anglo-Saxons of the Nordic race. The latter "Nordic" concept was promoted by certain writers, such as Madison Grant. According to Yaacov Shavit, this generated "radical Afrocentric theory, which followed the path of European racial doctrines". Writers who insisted that the Nordics were the purest representatives of the Aryan race indirectly encouraged "the transformation of the Hamitic race into the black race, and the resemblance it draws between the different branches of black forms in Asia and Africa."[28]

In response, historians published in the Journal of Negro History stressed the cross-fertilization of cultures between Africa and Europe: for instance, George Wells Parker adopted Sergi's view that the "civilizing" race had originated in Africa itself.[29][30] Similarly, black pride groups reinterpreted the concept of Hamitic identity for their own purposes. Parker founded the Hamitic League of the World in 1917 to "inspire the Negro with new hopes; to make him openly proud of his race and of its great contributions to the religious development and civilization of mankind." He argued for that "fifty years ago one would not have dreamed that science would defend the fact that Asia was the home of the black races as well as Africa, yet it has done just that thing."[31]

Timothy Drew and Elijah Muhammad developed from this the concept of the "Asiatic Blackman."[32] Many other authors followed the argument that civilization had originated in Hamitic Ethiopia, a view that became intermingled with biblical imagery. The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) (1920) believed that Ethiopians were the "mother race". The Nation of Islam asserted that the superior black race originated with the lost Tribe of Shabazz, which originally possessed "fine features and straight hair", but which migrated into Central Africa, lost its religion, and declined into a barbaric "jungle life".[28][33][34]

Afrocentric writers considered the Hamitic hypothesis to be divisive since they believed that it asserted that superior Africans were distinct from Negroid peoples. W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) thus argued that "the term Hamite under which millions of Negroes have been characteristically transferred to the white race by some eager scientists" was a tool to create "false writing on Africa".[35] By this, he was specifically alluding to certain Great Lakes region autochthones. With regard to the Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations of Northwest and Northeast Africa, however, Du Bois conceded that "the Libyans or Berbers were akin to the Egyptians," and that "toward the east and the Nile delta were the Egyptians, forefathers of the peoples today called Beja, Galla, Somali, and Danakil." He also acknowledged that "the Egyptian of predynastic times belonged then to the short, dark-haired, dark-eyed group of peoples, such as are found on both shores of the Mediterranean."[36]

Hamitic language family

These racial theories were developing alongside models of language. The German missionary Johann Ludwig Krapf (1810–81) was the first to use the term "Hamitic" in connection with languages, albeit in the Biblical sense to refer to all languages of Africa spoken by the purported descendants of Ham.

Friedrich Müller named the traditional Hamito-Semitic family in 1876 in his Grundriss der Sprachwissenschaft ("Outline of Linguistics"), and defined it as consisting of a Semitic group plus a "Hamitic" group containing Egyptian, Berber, and Cushitic; he excluded the Chadic group. It was the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius (1810–1884) who restricted Hamitic to the non-Semitic languages in Africa, which are characterized by a grammatical gender system. This "Hamitic language group" was proposed to unite various, mainly North-African, languages, including the Ancient Egyptian language, the Berber languages, the Cushitic languages, the Beja language, and the Chadic languages. Unlike Müller, Lepsius considered that Hausa and Nama were part of the Hamitic group. These classifications relied in part on non-linguistic anthropological and racial arguments. Both authors used the skin-color, mode of subsistence, and other characteristics of native speakers as part of their arguments that particular languages should be grouped together.[37]

In 1912, Carl Meinhof published Die Sprachen der Hamiten ("The Languages of the Hamites"), in which he expanded Lepsius's model, adding the Fula, Maasai, Bari, Nandi, Sandawe and Hadza languages to the Hamitic group. Meinhof's model was widely supported into the 1940s.[37] Meinhof's system of classification of the Hamitic languages was based on a belief that "speakers of Hamitic became largely coterminous with cattle herding peoples with essentially Caucasian origins, intrinsically different from and superior to the 'Negroes of Africa'."[38] But, in the case of the so-called Nilo-Hamitic languages (a concept he introduced), it was based on the typological feature of gender and a "fallacious theory of language mixture." Meinhof did this although earlier work by scholars such as Lepsius and Johnston had substantiated that the languages which he would later dub "Nilo-Hamitic" were in fact Nilotic languages, with numerous similarities in vocabulary to other Nilotic languages.[39]

Leo Reinisch (1909) had already proposed linking Cushitic and Chadic, while urging their more distant affinity with Egyptian and Semitic. However, his suggestion found little acceptance. Marcel Cohen (1924) rejected the idea of a distinct "Hamitic" subgroup, and included Hausa (a Chadic language) in his comparative Hamito-Semitic vocabulary. Finally, Joseph Greenberg's 1950 work led to the widespread rejection of "Hamitic" as a language category by linguists. Greenberg refuted Meinhof's linguistic theories, and rejected the use of racial and social evidence. In dismissing the notion of a separate "Nilo-Hamitic" language category in particular, Greenberg was "returning to a view widely held a half century earlier." He consequently rejoined Meinhof's so-called Nilo-Hamitic languages with their appropriate Nilotic siblings.[39] He also added (and sub-classified) the Chadic languages, and proposed the new name Afroasiatic for the family. Almost all scholars have accepted this classification as the new and continued consensus.

Greenberg's model was fully developed in his book The Languages of Africa (1963), in which he reassigned most of Meinhof's additions to Hamitic to other language families, notably Nilo-Saharan. Following Isaac Schapera and rejecting Meinhof, he classified the Hottentot language as a member of the Central Khoisan languages. To Khoisan he also added the Tanzanian Hadza and Sandawe, though this view remains controversial since some scholars consider these languages to be linguistic isolates.[40][41] Despite this, Greenberg's model remains the basis for modern classifications of languages spoken in Africa, and the Hamitic category (and its extension to Nilo-Hamitic) has no part in this.[41]

Anti-Hamitism

With the demise of the concept of Hamitic languages, the notion of a definable "Hamite" racial and linguistic entity was heavily criticised. In 1974, writing about the African Great Lakes region, Christopher Ehret described the Hamitic hypothesis as the view that "almost everything more un-'primitive', sophisticated or more elaborate in East Africa [was] brought by culturally and politically dominant Hamites, immigrants from the North into East Africa, who were at least part Caucasoid in physical ancestry".[42] He called this a "monothematic" model, which was "romantic, but unlikely" and "[had] been all but discarded, and rightly so". He further argued that there were a "multiplicity and variety" of contacts and influences passing between various peoples in Africa over time, something that he suggested the "one-directional" Hamitic model obscured.[42] With the maturation of multivariate skeletal analysis, Ehret would later clarify that the "Mediterranean Caucasoid" affinities present in the region were associated with ancestral Cushitic populations specifically, while the "Negroid" remains belonged to early Nilotic groups (see below).[43]

Reviewing Ehret's 1974 book, which he generally admired, the anthropologist and historical linguist Harold C. Fleming argued that Ehret was attempting to "exorcise the Hamites from East African history", and suggested that Ehret was motivated less by the evidence than to "establish his ideological purity". Fleming also asserted that there was a need to "arrest quarter of a century of excessive Anti-Hamitism in African studies". While accepting that racist ideas of a "Hamitic Herrenvolk" should be discarded, he argued that Ehret was "ostensibly aiming to denigrate the Cushites but giving seventy-seven percent of its space to them and their donations to other peoples". Fleming writes:[44]

In my opinion [...] it is time to arrest a quarter of a century of excessive anti-Hamitism in African studies [...] By [Hamitic], of course, was meant Caucasoid, but not just any Caucasoid. Hamitic as a catchall category always seems to presuppose biological resemblance to the ancient Egyptians, modern Berbers, or the better known Ethiopid types such as Beja, highland Abyssinians, Galla, or Somali[...] But anti-racism has not all been beneficial. A generation grew up drawing strange inferences from it. Since racism is "bad" politically and scientifically, and pro-Hamitic historical theories usually have been associated with racism, Hamites themselves are "bad" or unsavory or one should oppose any hypothesis which credits them with an important role in anything. Such an inference is a non sequitur and one which Greenberg never intended or supported. Is this prejudice immediately ascertainable; can its presence be easily shown, particularly among younger scholars? I believe this point is true but hard to test, particularly because I think it lies among the deep-seated attitudes an Africanist acquires in general training [...] Anti-racism, which has led to silly anti-Hamitism, finally led to falsehood when Ehret set out to restrict the role of the Cushites in eastern African history because they were a kind of Hamite.[44]

In his later The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History published in 1982, Ehret broadly agreed with Fleming on the persistence of ancestral ethnoracial boundaries in Africa despite later periods of contact. However, he still eschewed "Hamitic" terminology in favor of other nomenclature. He writes that skeletal evidence demonstrated that two distinct populations with different racial and geographical origins coexisted in the Rift Valley during the Neolithic: one group whose nearest affinities were with "Mediterranean Caucasoid" populations and Egyptians in particular, and a second group that was most closely related to modern "Negroid" populations. Through historical linguistics, Ehret generally identified the ancestral "Mediterranean Caucasoid" population with the makers of the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture, who spoke languages belonging to the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. He associated the "Negroid" remains with the makers of the Elmenteitan culture, who he indicated were likely speakers of languages from the Nilo-Saharan family.[43]

Archaeology

Certain archaeological industries have been associated with a hypothesized spread of ancestral Hamitic peoples in Africa. The main such prehistoric cultures are:[45][46]

| # | Prehistoric culture | Region | Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A-Group | Nile Valley | 3,800–3,100 BCE | Late Neolithic to early Bronze Age farming culture of Nubia. Its makers were physically akin to coeval groups in Upper Egypt, albeit culturally distinct.[47] |

| 2 | Badarian | Nile Valley | 4,400–4,000 BCE | Neolithic culture of Upper Egypt. One of the earliest agropastoral communities on the continent.[48] |

| 3 | C-Group | Nile Valley | 2,400–1,550 BCE | Bronze Age culture of Nubia. Its makers are thought to have spoken early Afroasiatic languages of the Berber branch.[49] |

| 4 | Capsian | Maghreb, Southwestern Europe | 10,000–6,000 BCE | Mesolithic industry concentrated in modern Tunisia and Algeria, as well as some areas between southern Spain and Sicily. Tentatively linked with the Proto-Afroasiatic speakers.[50] |

| 5 | Iberomaurusian | Maghreb | 20,000–10,000 BCE | Epipaleolithic stone industry of northwestern Africa. Its makers were osteologically similar to the Capsians, as well as the Kiffians of the Sahara and the Cro-Magnon populations of Europe.[51] |

| 6 | Kerma | Nile Valley | 2,500–1,500 BCE | Bronze Age culture of Nubia. Predecessor to the Meroitic civilization. The Kermans are believed to have spoken early Afroasiatic languages of the Cushitic branch.[49] |

| 7 | Merimde | Nile Valley | 5,000–4,200 BCE | Neolithic culture of Lower Egypt. Close ties with contemporaneous industries in the Levant.[52] |

| 8 | Naqada | Nile Valley | 4,400–3,000 BCE | Neolithic culture of Upper Egypt. Most widespread and enduring of the predynastic industries. Cradle of the ensuing Pharaonic culture.[53] |

| 9 | Savanna Pastoral Neolithic | African Great Lakes | 3,184 BCE–716 AD | Neolithic to Iron Age industry of southeastern Africa. Also known as the Stone Bowl Culture, its makers are believed to have spoken early South Cushitic languages.[54] |

| 10 | Tasian | Nile Valley | 4,500 BCE | Neolithic culture of Upper Egypt. One of the earliest local agropastoral communities. The Tasians were osteologically akin to the makers of the Merimde industry.[55] |

See also

- Abrahamic religions

- Afroasiatic languages

- Canaan (son of Ham)

- Generations of Noah

- Japhetites

- Semitic people

- Shem

References

- ↑ Allan, Keith (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. OUP Oxford. p. 275. ISBN 0199585849. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Everett Welmers, William (1974). African Language Structures. University of California Press. p. 16. ISBN 0520022106. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- 1 2 Ashley, Montagu (1960). An Introduction to Physical Anthropology – Third Edition. Charles C. Thomas Publisher. p. 456.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Seligman, Charles Gabriel (1930). The Races of Africa (PDF). Thornton Butterworth, Ltd. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ John Fage, William Tordoff (2013). A History of Africa. Routledge. pp. 7–10. ISBN 1317797272. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Evans, William M (February 1980), "From the Land of Canaan to the Land of Guinea: The Strange Odyssey of the 'Sons of Ham'", American Historical Review, 85: 15–43, doi:10.2307/1853423.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sanders, Edith R (1969), "The Hamitic Hypothesis: Its Origin and Functions in Time Perspective", Journal of African History, 10: 521–32, doi:10.1017/s0021853700009683.

- ↑ Swift, John N; Mammoser, Gigen (Fall 2009), "Out of the Realm of Superstition: Chesnutt's 'Dave's Neckliss' and the Curse of Ham", American Literary Realism, 42 (1): 3.

- ↑ Examples from Nigeria: Zachernuk, Philip (1994). "Of Origins and Colonial Order: Southern Nigerians and the 'Hamitic Hypothesis' c. 1870–1970". Journal of African History. 35 (3): 427–55. doi:10.1017/s0021853700026785. JSTOR 182643.

- ↑ Speke 1863, p. 247.

- ↑ Gourevitch 1999.

- ↑ Giuseppe Sergi, The Mediterranean Race: A Study of the Origin of European Peoples, (BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008), pp.42-43.

- ↑ Giuseppe Sergi, The Mediterranean Race: A Study of the Origin of European Peoples, (Forgotten Books), pp.39-44.

- ↑ Giuseppe Sergi, The Mediterranean Race: A Study of the Origin of European Peoples, (BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008), p.250.

- ↑ Giuseppe Sergi, The Mediterranean Race: A Study of the Origin of European Peoples, (Forgotten Books), p.36.

- ↑ Seligman, CG (1930), The Races of Africa, London, p. 96.

- 1 2 Rigby, Peter (1996), African Images, Berg, p. 68.

- ↑ Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, 4th edition, 1885-90, T11, p.476.

- ↑ Sergi, Giuseppe (1901), The Mediterranean Race, London: W Scott, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Coon, Carleton (1939). The Races of Europe (PDF). The Macmillan Company. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Seligman, Charles Gabriel (July–December 1913). "Some Aspects of the Hamitic Problem in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 43: 593–705. JSTOR 2843546.

- ↑ Speke, John Hanning (1868), Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile, Harper & bros, p. 514.

- 1 2 Keane, A.H. (1899). Man, Past and Present. p. 90.

- ↑ Boyd, James Penny (1889). Stanley in Africa: The Wonderful Discoveries and Thrilling Adventures of the Great African Explorer, and Other Travelers, Pioneers and Missionaries. Stanley Publishing Company. p. 722. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Gregory, JW (1968), The Great Rift Valley, Routledge, p. 356.

- ↑ Gatwa, Tharcisse (2005), The Churches and Ethnic Ideology in the Rwandan Crises, 1900–1994, OCMS, p. 65.

- ↑ Taylor, Christopher Charles (1999), Sacrifice as Terror: the Rwandan Genocide of 1994, Berg, p. 55.

- 1 2 Shavit 2001, pp. 26, 193.

- ↑ Parker, George Wells (1917), "The African Origin of the Grecian Civilization", Journal of Negro History: 334–44.

- ↑ Shavit 2001, p. 41.

- ↑ Parker, George Wells (1978) [Omaha, 1918], Children of the Sun (reprint ed.), Baltimore: Black Classic Press.

- ↑ "'The Asiatic Black Man': An African American Orientalism?", Journal of Asian American Studies, 4 (3): 193–208, October 2001, doi:10.1353/jaas.2001.0029

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help). - ↑ Ogbar, Jeffrey Ogbonna Green (2005), Black Power: Radical Politics and African American Identity, Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 144.

- ↑ X, Malcolm (1989), The End of White World Supremacy: Four Speeches, Arcade, p. 46.

- ↑ Du Bois, WEB (2000), Keita, Maghan, ed., Race and the Writing of History: Riddling the Sphinx, US: Oxford University Press, p. 78.

- ↑ Du Bois, William E. B. (2007). The World and Africa: An Inquiry Into the Part Which Africa Has Played in World History and Color and De: The Oxford W. E. B. Du Bois. OUP USA. p. 65. ISBN 0195325842. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- 1 2 Merritt Ruhlen, A Guide to the World's Languages: Classification, Stanford University Press, 1991, pp. 80–1

- ↑ Kevin Shillington, Encyclopedia of African History, CRC Press, 2005, p.797

- 1 2 Merritt Ruhlen, A Guide to the World's Languages, (Stanford University Press: 1991), p.109

- ↑ Sands, Bonny E. (1998) 'Eastern and Southern African Khoisan: evaluating claims of distant linguistic relationships.' Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung 14. Köln: Köppe.

- 1 2 Ruhlen, p.117

- 1 2 Ehret, C, Ethiopians and East Africans: The Problem of Contacts, East African Pub. House, 1974, p.8.

- 1 2 Christopher Ehret, Merrick Posnansky (ed.) (1982). The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History. University of California Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 0520045939. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- 1 2 Fleming, Harold C. "Ethiopians and East Africans". International Journal of African Historical Studies. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ↑ Honea, Kenneth Howard (1958). A Contribution to the History of the Hamitic Peoples of Africa (Acta ethnologica et linguistica, no. 5. ed.). Horn-Wien, F. Berger. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ McBurney, C. B. M. (1975). "Archaeological Context of Hamitic Languages in N.-Africa". Hamito-Semitica: 495–505. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ Shinnie, Peter L. (2013). Ancient Nubia. Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 1136164650. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Bard, Kathryn A. (2005). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 162. ISBN 1134665253. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- 1 2 Marianne Bechaus-Gerst, Roger Blench, Kevin MacDonald (ed.) (2014). The Origins and Development of African Livestock: Archaeology, Genetics, Linguistics and Ethnography - "Linguistic evidence for the prehistory of livestock in Sudan" (2000). Routledge. p. 453. ISBN 1135434166. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Bender, M. Lionel (September 1985). "The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History by Christopher Ehret, Merrick Posnansky". Language. 61 (3): 695. JSTOR 414395.

- ↑ Sereno PC, Garcea EAA, Jousse H, Stojanowski CM, Saliège J-F, Maga A, et al. (2008). "Lakeside Cemeteries in the Sahara: 5000 Years of Holocene Population and Environmental Change" (PDF). PLoS ONE. 3 (8). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002995. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Egypt Exploration Fund (2006). "The Merimde Culture". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 92. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ Török, László (2009). Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt, 3700 BC-AD 500. BRILL. p. 43. ISBN 9004171975. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ Daniel Stiles, S.C. Munro-Hay (1981). "Stone cairn burials at Kokurmatakore, northern Kenya" (PDF). Azania. XVI: 164. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ Forde-Johnston, James L. (1959). Neolithic cultures of North Africa: aspects of one phase in the development of the African stone age cultures. University of California. p. 58. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

Bibliography

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Hamitic. |

- Hamitic theory

- Honea, Kenneth Howard (1958), A Contribution to the History of the Hamitic Peoples of Africa, Horn-Wien, F. Berger.

- Seligman, CG (1930), The Races of Africa, London, p. 96.

- Sergi, Giuseppe (1901), The Mediterranean Race, London: W Scott, p. 41.

- Speke, JH (1863), Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile, London: Blackwoods.

- Other

- African Rights (1995), Rwanda: Death, Despair and Defiance, London.

- Gourevitch, Philip (1998), We Wish to Inform You that Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- ——— (September 1999) [1998], We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families: Letters From Rwanda, New York: Picador, 0-31224335-9, 368 pp.

- Mamdani, Mahmoud (2002), When Victims become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism and Genocide in Rwanda, Princeton University Press.

- Shavit, Yaacov (2001), History in Black: African-Americans in Search of an Ancient Past, Routledge.