Group Representation Constituency

.svg.png) |

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Singapore |

| Constitution |

| Foreign relations |

|

Related topics |

A Group Representation Constituency (GRC) is a type of electoral division or constituency in Singapore in which teams of candidates, instead of individual candidates, compete to be elected into Parliament as the Members of Parliament (MPs) for the constituency. The Government stated that the GRC scheme was primarily implemented to enshrine minority representation in Parliament: at least one of the MPs in a GRC must be a member of the Malay, Indian or another minority community of Singapore. In addition, it was economical for town councils, which manage public housing estates, to handle larger constituencies.

The GRC scheme came into effect on 1 June 1988. Prior to that date, all constituencies were Single Member Constituencies (SMCs). Now, the Parliamentary Elections Act (Cap. 218, 2008 Rev. Ed.) ("PEA") states that there must be at least eight SMCs, and the number of MPs to be returned by all GRCs cannot be less than a quarter of the total number of MPs. Within those parameters the total number of SMCs and GRCs in Singapore and their boundaries are not fixed but are decided by the Cabinet, taking into consideration the recommendations of the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee.

According to the Constitution and the PEA, there must be between three and six MPs in a GRC. The precise number of MPs in each GRC is declared by the President at the Cabinet's direction prior to a general election. For the purposes of the 2015 general election, there were 13 SMCs and 16 GRCs, and each GRC had between four and six MPs.

Critics disagree with the government's justifications for introducing the GRC scheme, noting that the proportion of minority MPs per GRC has decreased with the advent of five-member and six-member GRCs. By having teams of candidates standing for election for GRCs helmed by senior politicians, the ruling People's Action Party has also used GRCs as a means for bringing first-time candidates into Parliament. Moreover, the GRC scheme is also said to disadvantage opposition parties because it is more difficult for them to find enough candidates to contest GRCs. Furthermore, it is said that the GRC scheme means that electors have unequal voting power, weakens the relationship between electors and MPs, and entrenches racialism in Singapore politics.

Introduction of the scheme

There are two types of electoral division or constituency[1] in Singapore: the Single Member Constituency (SMC) and the Group Representation Constituency (GRC). In a GRC, a number of candidates comes together to stand for elections to Parliament as a group. Each voter of a GRC casts a ballot for a team of candidates, and not for individual candidates. The GRC scheme was brought into existence on 1 June 1988 by the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 1988[2] and the Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Act 1988.[3]

The original stated purpose of GRCs was to guarantee a minimum representation of minorities in Parliament and ensure that there would always be a multiracial Parliament instead of one made up of a single race.[4] Speaking in Parliament during the debate on whether GRCs should be introduced, First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Goh Chok Tong said he had first discussed the necessity of ensuring the multiracial nature of Parliament with Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in July 1982. Then, Lee had expressed concern about the voting patterns of younger Singaporeans, who appeared to be apathetic to the need of having a racially balanced slate of candidates. He was also worried about more Singaporeans voting along racial lines, which would lead to a lack of minority representation in Parliament.[5]

He had also proposed to twin constituencies and have Members of Parliament (MPs) contest as a pair, one of whom had to be from a minority community. However, Malay MPs were upset that this implied they were not electable on their own merits. Feeling that the twinning of constituencies would lead to Malay MPs losing confidence and self-respect, the Government dropped the proposal.[6]

Therefore, the Government felt that the best way to ensure minority representation in Parliament was to introduce the GRC scheme. In addition, it took the view that such a scheme would complement the introduction of town councils to manage public housing estates, as it would be economical for a town council to manage a group of three constituencies.[7] Subsequently, in 1991, the Government said that GRCs also minimized the need to redraw the boundaries of constituencies which had grown too big for the MPs serving them, and, in 1996, GRCs were said to provide Community Development Councils with the critical mass of residents that they needed to be effective.[8]

Three proposals for minority representation in Parliament had been considered by a 1966 Constitutional Commission chaired by the Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin. The first was to have a committee of representatives of minorities that would elect three persons from amongst its members to represent minorities in Parliament.[9] However, this was rejected as the Commission felt that it would be an inappropriate and retrogressive move in that unelected members should not be allowed to dilute the elected chamber.[10] The second proposal, which was to have proportional representation,[11] was also rejected on the grounds that it would intensify party politics along racial lines and eventually "perpetuate and accentuate racial differences". This would then make it increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to achieve a single homogeneous community out of the many races that form the population of the Republic.[12] The third proposal was to have an upper house in Parliament composed of members elected or nominated to represent the racial, linguistic and religious minorities in Singapore.[13] However, this was rejected as being backward-looking since politicians should attain a seat in Parliament through taking part in elections.[14]

Operation

Number and boundaries of electoral divisions

Apart from the requirement that there must be at least eight SMCs,[15] the total number of SMCs and GRCs in Singapore and their boundaries are not fixed. The number of electoral divisions and their names and boundaries are specified by the Prime Minister from time to time by notification in the Government Gazette.[16]

Since 1954, a year ahead of the 1955 general election, an Electoral Boundaries Review Committee (EBRC) has been appointed to advise the executive on the number and geographical division of electoral divisions. Even though neither the Constitution nor any law requires this to be done, the Prime Minister has continued to do so from Singapore's independence in 1965. This is generally done just before a general election to review the boundaries of electoral divisions and recommend changes.[17] In recent decades, the Committee has been chaired by the Cabinet Secretary and has had four other members who are senior public servants. In the EBRC appointed before the general election of 2006, these were the head of the Elections Department, the Chief Executive Officer of the Singapore Land Authority, the Deputy CEO of the Housing and Development Board and the Acting Chief Statistician.[18][19] Since the Committee is only convened shortly before general elections, the preparatory work for boundary delimitation is done by its secretariat the Elections Department, which is a division of the Prime Minister's Office.[20]

The EBRC's terms of reference are issued by the Prime Minister, and are not embodied in legislation. In giving recommendations for boundary changes over the years, the Committee has considered various factors, including using hill ridges, rivers and roads as boundaries rather than arbitrarily drawn lines; and the need for electoral divisions to have approximately equal numbers of voters so that electors' votes carry the same weight regardless of where they cast their ballots. In 1963, the EBRC adopted a rule allowing the numbers of voters in divisions to differ by no more than 20%. The permitted deviation was increased to 30% in 1980. It is up to the Cabinet to decide whether or not to accept the Committee's recommendations.[21]

Requirements of GRCs

All the candidates in a GRC must either be members of the same political party or independent candidates standing as a group,[22] and at least one of the candidates must be a person belonging to the Malay, Indian or some other minority community.[23] A person is regarded as belonging to the Malay community if, regardless of whether or not he or she is of the Malay race, considers himself or herself to be a member of the community and is generally accepted as such by the community. Similarly, a person will belong to the Indian community or some other minority community if he or she considers himself or herself a member and the community accepts him or her as such.[24] The minority status of candidates is determined by two committees appointed by the President, the Malay Community Committee and the Indian and Other Minority Communities Committee.[25] Decisions of these committees are final and conclusive, and may not be appealed against or called into question in any court.[26]

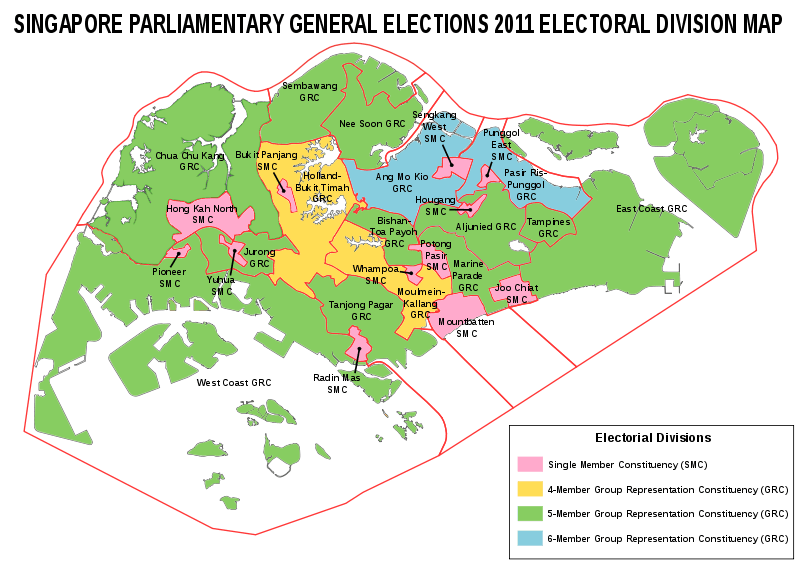

The President, at the Cabinet's direction, declares the electoral divisions that are to be GRCs; the number of candidates (three to six)[27] to stand for Parliament in each GRC; and whether the minority candidates in each GRC are to be from the Malay, Indian, or other minority communities.[28] The number of GRCs in which at least one MP must be from the Malay community must be three-fifths of the total number of GRCs,[29] and the number of MPs to be returned by all GRCs cannot be less than a quarter of the total number of MPs to be returned at a general election.[30] For the 2011 general election, there were 12 SMCs and 15 GRCs.[31]

An electoral division which is a GRC returns the number of MPs designated for the constituency by the President to serve in Parliament.[32] A group of individuals standing together in a GRC is voted for as a team, and not as individual candidates. In other words, a successful voter's single vote in an SMC sends to Parliament one MP, and a GRC sends a group of MPs depending on how many have been designated for that GRC. All elected MPs are selected on a simple plurality voting ("first past the post") basis.[33]

A by-election need not be held to fill a vacancy in any GRC triggered by the death or resignation of an MP or some other reason. A by-election is required only if all the MPs in a GRC vacate their Parliamentary seats.[34][35] Assuming that such a situation does arise, the Prime Minister would be obliged to call a by-election within a reasonable time,[36] unless he intends to call a general election in the near future.[37]

Modifications

In 1988, 39 SMCs were grouped into 13 three-member GRCs, making up 39 out of a total of 81 elected seats in Parliament. The Constitution and the Parliamentary Elections Act were changed in 1991[38] and again in 1996[39] to increase the maximum number of MPs in each GRC from three to four, and then to six. In the 2001 general election, three- and four-member GRCs were replaced by five- and six-member GRCs. There were nine five-member GRCs and five six-member GRCs, making up 75 out of the 84 elected seats in Parliament. This arrangement remained unchanged at the 2006 elections.[40]

On 27 May 2009, the Government announced that it would refine the size and number of GRCs. This could be achieved without amending either the Constitution or the Parliamentary Elections Act. Instead, when the next EBRC was appointed, its terms of reference would instruct the Committee to plan for fewer six-member GRCs than at present, and to reduce the average size of each GRC. The average size of GRCs at that time was 5.4 MPs because there were only five-member and six-member GRCs. The new average, however, would not exceed five MPs.[4]

In addition, to ensure that the number of SMCs kept pace with the increase in voters and hence the number of MPs, the EBRC's terms of reference would state that there should be at least 12 SMCs. The rationale given for these changes was that the GRC scheme would work better and the link between voters and their MPs would be strengthened.[4] In the 2011 general election, SMCs returned to Parliament 12 MPs and 15 GRCs a total of 75 MPs.[31]

Assessment

Advantages

As Article 39A of the Constitution states, the GRC scheme entrenches the presence of minority MPs in Parliament, ensuring that interests of minority communities are represented in Parliament.[41] Article 39A(1)(a) of the Constitution allows for a maximum number of six MPs for each GRC so as to provide flexibility in ensuring that a GRC with a rapidly expanding population is properly managed.[42] As the population of a constituency grows, it becomes increasingly difficult for an MP to singlehandedly represent all his or her constituents' views. A team of MPs arguably has greater access to more constituents, and the fact that there are different MPs in the team suggests they can more effectively provide representation in Parliament of a wide range of constituents' views.[4]

Criticisms of the scheme

Diversion from original purpose

The official justification for the GRC scheme is to entrench minority representation in Parliament. However, opposition parties have questioned the usefulness of GRCs in fulfilling this purpose, especially since Singapore has not faced the issue of minorities being under-represented in Parliament. In fact, statistics show that all PAP minority candidates have won regularly and that the only two MPs to lose their seats in 1984 were Chinese. One of them was beaten by a minority candidate.[43] In addition, Joshua Benjamin Jeyaratnam of the Workers' Party of Singapore won a by-election in 1981 at Anson, a largely Chinese constituency, and the first elected Chief Minister of Singapore was David Marshall who was Jewish. Technically, as the size of GRCs has increased, the minority has had less representation overall as the proportion of minority MPs per GRC has been reduced. Since minority MPs are a numerical minority in Parliament, their political clout has also been reduced.[44]

Furthermore, the GRC scheme is now used as a recruiting tool for the PAP. In 2006, Goh Chok Tong stated, "Without some assurance of a good chance of winning at least their first election, many able and successful young Singaporeans may not risk their careers to join politics".[45] Indeed, every PAP GRC team is helmed by a major figure such as a minister, and this allows new candidates to ride on the coat-tails of the experienced PAP members.[46] Since 1991, the PAP has generally not fielded first-time candidates in SMC wards. On the other hand, one of the "in-built weaknesses" of GRCs may be that "through no fault of their own or that of their team", "high-value" MPs can be voted out; this was said to have occurred when former Minister for Foreign Affairs George Yeo lost his parliamentary seat to a Workers' Party of Singapore team in Aljunied GRC at the 2011 general election.[47]

It is also said that GRCs serve more as administrative tools than to ensure minority representation. The size of GRCs was increased to take advantage of economies of scale when managing the wards. However, whether GRCs are required for this purpose is arguable, as Goh Chok Tong stated in 1988 that MPs in SMCs could still group together after elections to enjoy economies of scale.[48]

Opposition parties disadvantaged

The GRC scheme has also been criticized for raising the bar for the opposition in elections. First, opposition parties may find it harder to find competent candidates, including minority candidates, to form teams to contest GRCs. Goh Chok Tong has acknowledged that the GRC scheme benefits the PAP as they can put together stronger teams.[49] With the GRC system the threshold for votes for the opposition is also increased, and opposition parties have to take a gamble and commit huge proportions of their resources to contest GRCs.[46] Each candidate in a GRC is required to deposit a sum equal to 8% of the total allowances payable to an MP in the calendar year preceding the election, rounded to the nearest S$500.[50] At the 2011 general election, the deposit was $16,000.[51] Unsuccessful candidates have their deposits forfeited if they do not receive at least one-eighth of the total number of votes polled in the GRC.[52] Critics have noted that the number of walkovers has generally increased since the introduction of GRCs. To date, only one opposition party, the Workers' Party, has won a GRC: Aljunied, in the 2011 general election.[53]

Creation of unequal voting power

GRCs have been criticized as creating unequal voting powers between electors. At present, one vote in a GRC ward returns five or six candidates into Parliament, compared with one vote in a SMC ward, which only returns one candidate. The GRC scheme has also diluted electors' voting power. For instance, in an SMC ward there are around 14,000 voters, compared to 140,000 voters in a five- or six-member GRC. Thus, the power of each vote in a GRC is lower than in an SMC, as each voter in a GRC finds it harder to vote out an MP that he or she does not like.[54] The situation is compounded by the fact that a 30% deviation from equality of electoral divisions is tolerated. Another commentator has pointed out that the current MP-to-voter guide ratio is one MP to 26,000 voters, which implies that the number of voters in an electoral division can vary between 18,200 and 33,800. By extrapolation, a five-member GRC can have between 91,000 and 169,000 voters, a difference of 86%.[55]

Weakening of voter–MP relationship

Critics have noted that the credibility and accountability of some candidates may be reduced because in a GRC the members of the team who are popular "protect" less popular members from being voted out. It has been said that the relationship between the electorate and their representatives is also weakened, because the relationship is between the individual and the GRC team rather than between the individual and a particular MP.[46] Improving the link between voters and MPs, and to make the latter more accountable was the reason for the changes proposed in 2009 to introduce more SMCs and to reduce the size of GRCs.[4]

Enshrining of racialism

Even though the GRC scheme is intended to ensure minority representation in Parliament, it can be said that the scheme emphasizes racial consciousness and hence widens the gap between races. It may undermine the esteem of minority candidates as they would not be sure if they are elected on their own merit, or due to the scheme and the merits of the rest of the team of MPs. This would result in minority candidates resenting that they are dependent on the majority to enter Parliament, and the majority candidates believing that minority candidates have insufficient ability. It has also been claimed that the GRC scheme demeans the majority of Singaporeans as it assumes that they are not able to see the value or merit of minority candidates, and only vote for candidates with whom they share a common race, culture and language.[56]

Law of large numbers

Derek da Cunha has proposed that the law of large numbers favours the GRC system. According to the theory, the large number of voters from GRC wards generally, though not necessarily always, reflects the popular vote. This was evident at the 2006 elections, at which the PAP garnered an average of 67.04% of the votes in a contested GRC, while the average was 61.67% for a SMC ward. The national average for the 2006 elections was 66.6%. Similar trends can be seen from previous elections. In fact, the percentage difference in the PAP votes between SMCs and GRCs grew from 3% in 1991, and remained stable at around 5% in the 1997, 2001 and 2006 elections. This may be attributable to the enlargement of the size of GRCs in 1997 which gave greater effect to the law of large numbers.[57]

See also

- Constituencies of Singapore

- Non-constituency Member of Parliament

- Presidential Council for Minority Rights

Notes

- ↑ Constitution, Art. 39(3): "In this Article and in Articles 39A and 47, a constituency shall be construed as an electoral division for the purposes of Parliamentary elections."

- ↑ Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 1988 (No. 9 of 1988). The Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Bill (No. B 24 of 1987) was read in Parliament for the first time on 30 November 1987. The Second Reading took place on 12 January 1988, and it was referred to a select committee which presented its report on 5 May 1988. The bill was read for the third time and passed on 18 May 1988. It came into force on 31 May 1988.

- ↑ Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Act 1988 (No. 10 of 1988). The Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Bill (No. B 23 of 1987) had its First and Second Readings on 30 November 1987 and 11–12 February 1988 respectively. Like the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Bill, it was committed to a select committee which rendered its report on 5 May 1988. The bill was read for a third time and passed on 18 May 1988 and came into force on 1 June 1988, a day after the 1988 Act amending the Constitution commenced.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lee Hsien Loong (Prime Minister), "President's address: Debate on the address", Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (27 May 2009), vol. 86, col. 493ff.

- ↑ Goh Chok Tong (Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence), speech during the Second Reading of the Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Bill, Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (11 January 1988), vol. 50, col. 180.

- ↑ Goh, Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Bill, cols. 180–183; Edwin Lee (2008), Singapore: The Unexpected Nation, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p. 499, ISBN 978-981-230-796-5.

- ↑ Goh, Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Bill, cols. 183–184.

- ↑ Lydia Lim; Zakir Hussain (2 August 2008), "GRCs: 20 years on", The Straits Times.

- ↑ Report of the Constitutional Commission, 1966, Singapore: Government Printer, 1966, OCLC 51640681, para. 46(1).

- ↑ Constitutional Commission, 1966, para. 47.

- ↑ Constitutional Commission, 1966, para. 46(2).

- ↑ Constitutional Commission, 1966, para. 48.

- ↑ Constitutional Commission, 1966, para. 46(3).

- ↑ Constitutional Commission, 1966, para. 49.

- ↑ Parliamentary Elections Act (Cap. 218, 2007 Rev. Ed.) ("PEA"), s. 8A(1A).

- ↑ PEA, ss. 8(1) and (2).

- ↑ S. Ramesh (30 October 2010), Singapore's Electoral Boundaries Review Committee convened, Channel NewsAsia.

- ↑ Tommy Koh, ed. (2006), "Electoral Boundaries Review Committee", Singapore: The Encyclopedia, Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, p. 174, ISBN 978-981-4155-63-2, archived from the original on 25 August 2007.

- ↑ Li Xueying (18 September 2010), "Making sense of electoral boundaries", The Straits Times, pp. A38–A39 at A39.

- ↑ Li, "Making sense of electoral boundaries", p. A38.

- ↑ Li, "Making sense of electoral boundaries", pp. A38–A39.

- ↑ Constitution, Art. 39A(2)(c); PEA, s. 27A(3).

- ↑ Constitution, Art. 39A(2)(a), PEA, s. 27A(4).

- ↑ Constitution, Art. 39A(4); PEA, s. 27A(8).

- ↑ PEA, ss. 27C(1)–(3).

- ↑ PEA, s. 27C(8).

- ↑ Constitution, Art. 39A(1)(a); PEA, s. 8A(1)(a).

- ↑ PEA, ss. 8A(1)(a) and (b).

- ↑ If the three-fifths figure is not a whole number, it is rounded to the next higher whole number: PEA, s. 8A(3).

- ↑ PEA, s. 8A(2).

- 1 2 Types of Electoral Divisions, Elections Department, 24 October 2011, archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- ↑ PEA, s. 22.

- ↑ See, for instance, the PEA, s. 49(7E)(a): "... the Returning Officer shall declare the candidate or (as the case may be) group of candidates to whom the greatest number of votes is given to be elected".

- ↑ PEA, s. 24(2A).

- ↑ Vellama d/o Marie Muthu v. Attorney-General [2013] SGCA 39, [2013] 4 S.L.R. 1 at 38, para. 80, Court of Appeal (Singapore). On the other hand, in the Vellama case, the Court of Appeal held that the Prime Minister has a duty to call a by-election when a casual vacancy arises in a Single Member Constituency: Vellama, p. 38, para. 79.

- ↑ Interpretation Act (Cap. 1, 2002 Rev. Ed.), s. 52.

- ↑ Vellama, p. 35, para. 82.

- ↑ Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 1991 (No. 5 of 1991); Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Act 1991 (No. 9 of 1991).

- ↑ Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 1996 (No. 41 of 1996); Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Act 1996 (No. 42 of 1996).

- ↑ Parliamentary Elections (Declaration of Group Representation Constituencies) Order 2006 (S 146/2006); Types of electoral divisions, Elections Department, 7 April 2009, archived from the original on 15 July 2009, retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ The Constitution, Art. 39A(1), states: "The Legislature may, in order to ensure the representation in Parliament of Members from the Malay, Indian and other minority communities, by law make provision for ... any constituency to be declared by the President, having regard to the number of electors in that constituency, as a group representation constituency to enable any election in that constituency to be held on a basis of a group of not less than 3 but not more than 6 candidates".

- ↑ Goh Chok Tong (Prime Minister), speech during the Second Reading of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Bill, Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (28 October 1996), vol. 66, col. 756.

- ↑ Christopher Tremewan (1994), The Political Economy of Social Control in Singapore, Basingstoke, Hants: Macmillan in association with St. Antony's College, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-312-12138-9.

- ↑ Lily Zubaidah Rahim (1998), The Singapore Dilemma: The Political and Educational Marginality of the Malay Community, New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-983-56-0032-6.

- ↑ Li Xueying (27 June 2006), "GRCs make it easier to find top talent: SM: Without good chance of winning at polls, they might not be willing to risk careers for politics", The Straits Times, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Bilveer Singh (2006), Politics and Governance in Singapore: An Introduction, Singapore: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-126184-5.

- ↑ "Where next for George Yeo? [editorial]", The Straits Times, p. A20, 10 May 2011.

- ↑ Quoted in Sylvia Lim (NCMP), "Parliamentary elections", Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (27 August 2008), vol. 84, col. 3328ff.

- ↑ Hussin Mutalib (November 2002), "Constitutional-Electoral Reforms and Politics in Singapore", Legislative Studies Quarterly, 27 (4): 659–672 at 665, doi:10.3162/036298002X200765.

- ↑ PEA, s. 28(1).

- ↑ Notice of Election for All Electoral Divisions (Gazette Notification (G.N.) No. 1064/2011) dated 19 April 2011, archived from the original on 9 May 2011.

- ↑ PEA, s. 28(4A)(b).

- ↑ "81–6: Workers' Party wins Aljunied GRC; PAP vote share dips to 60.1%", The Sunday Times, pp. 1 & 4, 8 May 2011; Low Chee Kong (8 May 2011), "A new chapter and a time for healing: PAP wins 81 out of 87 seats; WP takes Hougang, Aljunied", Today (Special Ed.), pp. 1 & 4, archived from the original on 9 May 2011.

- ↑ Kenneth Paul Tan (2007), Renaissance Singapore?: Economy, Culture and Politics, Singapore: NUS Press, ISBN 978-9971-69-377-0.

- ↑ Eugene K[heng] B[oon] Tan (1 November 2010), "A 30-per-cent deviation is too wide: Redrawing of electoral boundaries must avoid being seen as gerrymandering", Today, p. 14, archived from the original on 13 December 2010.

- ↑ GRC hinders building Singaporean identity, Think Centre, 26 November 2002, archived from the original on 27 October 2007, retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ↑ Derek da Cunha (1997), The Price of Victory: The 1997 Singapore General Election and Beyond, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-981-305-588-9, ISBN 978-981-3055-66-7.

References

Legislation

- Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1999 Reprint).

- Parliamentary Elections Act (Cap. 218, 2007 Rev. Ed.) ("PEA").

Other works

- Singh, Bilveer (2006), Politics and Governance in Singapore: An Introduction, Singapore: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-126184-5.

- Goh, Chok Tong (Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence), speech during the Second Reading of the Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Bill, Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (11 January 1988), vol. 50, cols. 178–192.

- Li, Xueying (18 September 2010), "Making sense of electoral boundaries", The Straits Times, pp. A38–A39.

- Report of the Constitutional Commission, 1966 [Chairman: Wee Chong Jin], Singapore: Government Printer, 1966, OCLC 51640681.

Further reading

Articles and websites

- Lua, Ee Laine; Sim, Disa Jek Sok; Koh, Christopher Theng Jer (1996), "Principles and Practices of Voting: The Singapore Electoral System", Singapore Law Review, 17: 244–321 at 299–303.

- Tan, Eugene K[heng] B[oon] (November 2005), "Multiracialism Engineered: The Limits of Electoral and Spatial Integration in Singapore", Ethnopolitics, 4 (4): 413–428, doi:10.1080/17449050500348659, also published in Bieber, Florian; Wolff, Stefan, eds. (2007), The Ethnopolitics of Elections, London; New York, N.Y.: Routledge, pp. 53–68, ISBN 978-0-415-40047-3.

- Tan, Eugene; Chan, Gary (13 April 2009), "The Legislature", The Singapore Legal System, SingaporeLaw.sg, Singapore Academy of Law, archived from the original on 1 December 2010, retrieved 1 December 2010.

- Tan, Kevin Yew Lee (1992), "Constitutional Implications of the 1991 Singapore General Election", Singapore Law Review, 13: 26–59.

- Tan, Kevin Y[ew] L[ee] (1997), "Is Singapore's Electoral System in Need of Reform?", Commentary, 14: 109–117.

- Tey, Tsun Hang (December 2008), "Singapore's Electoral System: Government by the People?", Legal Studies, 28 (4): 610–628, doi:10.1111/j.1748-121X.2008.00106.x.

- Thio, Li-ann (2002), "The Right to Political Participation in Singapore: Tailor-making a Westminster-modelled Constitution to Fit the Imperatives of 'Asian' Democracy", Singapore Journal of International and Comparative Law, 6: 181–243.

Books

- Chan, Helena H[ui-]M[eng] (1995), "Parliament and Law Making", The Legal System of Singapore, Singapore: Butterworths Asia, pp. 41–68, ISBN 978-0-409-99789-7.

- Chua, Beng Huat (1995), Communitarian Ideology and Democracy in Singapore, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-16465-8.

- Hussin Mutalib (2003), Parties and Politics: A Study of Opposition Parties and the PAP in Singapore, Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, ISBN 978-981-210-211-9, ISBN 978-981-210-268-3 (pbk.).

- Report of the Select Committee on the Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Bill (Bill No. 23/87) and the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill (Bill No. 24/87) [Parl. 3 of 1988], Singapore: Printed for the Government of Singapore by Singapore National Printers, 1988, OCLC 30875454.

- Rodan, Garry, ed. (1993), Singapore Changes Guard: Social, Political and Economic Directions in the 1990s, New York, N.Y.: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-09687-8.

- Tan, Kevin Y[ew] L[ee] (2011), "Making Law: Parliament", An Introduction to Singapore's Constitution (rev. ed.), Singapore: Talisman Publishing, pp. 33–60 at 53–55, ISBN 978-981-08-6456-9.

- Tan, Kevin Y[ew] L[ee]; Thio, Li-ann (2010), "The Legislature", Constitutional Law in Malaysia and Singapore (3rd ed.), Singapore: LexisNexis, pp. 299–360 at 310, ISBN 978-981-236-795-2.

- Thio, Li-ann (2012), "The Legislature and the Electoral System", A Treatise on Singapore Constitutional Law, Singapore: Academy Publishing, pp. 285–359 at 332–355, ISBN 978-981-07-1515-1.

External links

- Official website of the Elections Department

- Official website of the Parliament of Singapore

- Singapore Elections