Greyhound

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other names | English Greyhound | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | British Isles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Greyhound is a breed of dog, a sighthound which has been bred for coursing game and Greyhound racing. Since the rise in large-scale adoption of retired racing Greyhounds, it has seen a resurgence in popularity as a family pet.

According to Merriam-Webster, a Greyhound is "any of a breed of tall slender graceful smooth-coated dogs characterized by swiftness and keen sight...of several related dogs."[1]

It is a gentle and intelligent breed whose combination of long, powerful legs, deep chest, flexible spine and slim build allows it to reach average race speeds in excess of 64 kilometres per hour (40 mph).[2][3][4] The Greyhound can reach a full speed of 70 kilometres per hour (43 mph) within 30 metres (98 ft) or six strides from the boxes, traveling at almost 20 metres per second (66 ft/s) for the first 250 metres (820 ft) of a race.[5][6]

Appearance

Males are usually 71 to 76 centimetres (28 to 30 in) tall at the withers and weigh around 27 to 40 kilograms (60 to 88 lb). Females tend to be smaller with shoulder heights ranging from 68 to 71 centimetres (27 to 28 in) and weights from less than 27 to 34 kilograms (60 to 75 lb). Greyhounds have very short fur, which is easy to maintain. There are approximately thirty recognized colour forms, of which variations of white, brindle, fawn, black, red and blue (gray) can appear uniquely or in combination.[7] Greyhounds are dolichocephalic, with a skull which is relatively long in comparison to its breadth, and an elongated muzzle.

Temperament

Greyhounds are known for having "cat-like" personalities. They can be aloof and indifferent to strangers, but are affectionate with their own pack. They are generally docile, lazy, easy-going, and calm.

Greyhounds wear muzzles during racing, which can lead some to believe it is an aggressive dog, but this is not true. Muzzles are worn to prevent injuries resulting from dogs nipping one another during or immediately after a race, when the 'hare' has disappeared out of sight and the dogs are no longer racing but remain excited. In a study from 1982 - 2014 recording reports of dog bites, there was only one recorded greyhound bite on a human in 22 years. [8]

Contrary to popular belief, adult Greyhounds do not need extended periods of daily exercise, as they are bred for sprinting rather than endurance. Greyhound puppies that have not been taught how to utilize their energy, however, can be hyperactive and destructive if not given an outlet, and they require more experienced handlers.[9]

Pets

Greyhound owners and adoption groups consider Greyhounds to be wonderful pets.[10] Greyhounds are quiet, gentle, and loyal to owners. They are very loving creatures, and they enjoy the company of their humans and other dogs. Whether a Greyhound enjoys the company of other small animals or cats depends on the individual dog's personality. Greyhounds will typically chase small animals; those lacking a high 'prey drive' will be able to coexist happily with toy dog breeds and/or cats. Many owners describe their Greyhounds as "45-mile-per-hour couch potatoes".[11]

Greyhounds live most happily as pets in quiet environments.[12] They do well in families with children as long as the children are taught to treat the dog properly and with politeness and appropriate respect.[13] Greyhounds have a sensitive nature, and gentle commands work best as training methods.

Greyhounds cope well as three-legged dogs.[14]

Occasionally, a Greyhound may bark; however, Greyhounds are generally not barkers, which is beneficial in suburban environments, and they are usually as friendly to strangers as they are with their own family.[15]

A very common misconception regarding Greyhounds is that they are hyperactive. In retired racing Greyhounds, this is usually not the case.[16] Greyhounds can live comfortably as apartment dogs, as they do not require much space and sleep close to 18 hours per day. In fact, due to their calm temperament, Greyhounds can make better "apartment dogs" than smaller, more active breeds.

At most race tracks, Greyhounds are housed in crates for sleeping. Most such animals know no other way of life than to remain in a crate the majority of the day. Crate training a retired Greyhound in a home is therefore generally extremely easy.

Many Greyhound adoption groups recommend that owners keep their Greyhounds on a leash whenever outdoors, except in fully enclosed areas.[17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24] This is due to their prey-drive, their speed, and the assertion that Greyhounds have no road sense.[25] In some jurisdictions, it is illegal for Greyhounds to be allowed off-lead[26] even in off-lead dog parks, so it is important to be familiar with the relevant local laws and regulations. Due to their size and strength, adoption groups recommend that fences be between 4 and 6 feet, to prevent them from jumping out.[17]

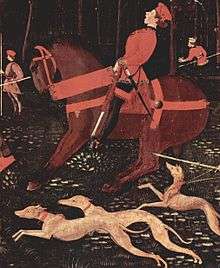

Coursing

The original primary use of Greyhounds, both in the British Isles and on the Continent of Europe, was in the coursing of deer. Later, they specialized in competition hare coursing.[27] Some Greyhounds today are still used for coursing, although artificial lure sports like lure coursing and racing are far more common and popular. Many breeders argue that coursing is still important. This is the case particularly in Ireland, where many of the world’s leading breeders are based. A bloodline that has produced a champion on the live hare coursing field is often crossed with track lines in order to keep the early pace (e.g. speed over first 100 yards), which Greyhounds are renowned for, prominent in the line. Many of the leading sprinters over 300 yards to 550 yards have bloodlines traceable back through Irish sires within a few generations that won events such as the Irish Coursing Derby or the Irish Cup.[28][29] The majority of pure-bred Greyhounds are whelped in Ireland. Researching via Greyhound data websites will note coursing champions within a few generations in the pedigree of track racing champions.

Racing

Until the early twentieth century, Greyhounds were principally bred and trained for hunting and coursing. During the 1920s, modern greyhound racing was introduced into the United States and England (Belle Vue Stadium, Manchester, July 1926), as well as Northern Ireland (Celtic Park (Belfast), April 1927) and the Republic of Ireland (Shelbourne Park, Dublin).

Australia also has a significant racing culture.[30][31][32] However, the 2015 live baiting scandal and adverse media coverage led to a Special Commission of Inquiry into the Greyhound Racing Industry in NSW.[33] On 7 July 2016, New South Wales Premier Mike Baird announced that greyhound racing was to be banned in the state from 1 July 2017 after the inquiry found evidence of systemic animal cruelty, including mass greyhound killings and live baiting.[33][34][35] After the NSW announcement, Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Chief Minister Andrew Barr stated that greyhound racing would be banned in the ACT.[36]

Aside from professional racing, many Greyhounds enjoy success on the amateur race track. Organizations like the Large Gazehound Racing Association (LGRA) and the National Oval Track Racing Association (NOTRA) provide opportunities for Greyhounds and other sighthound breeds to compete in amateur racing events all over the United States.[37][38]

Companion

Historically, the Greyhound has, since its first appearance as a hunting type and breed, enjoyed a specific degree of fame and definition in Western literature, heraldry and art as the most elegant or noble companion and hunter of the canine world. In modern times, the professional racing industry with its large numbers of track-bred Greyhounds, as well as the international adoption programs aimed at rescuing and re-homing dogs surplus to the industry, have redefined the breed in their almost mutually dependent pursuit of its welfare, as a sporting dog that will supply friendly companionship in its retirement.[39] Outside the racing industry and coursing community, the Kennel Clubs' registered breed still enjoys a modest following as a show dog and pet. There is an emerging pattern visible in recent years (2009–2010) of a significant decline in track betting and multiple track closures in the US, which will have consequences for the origin of future companion Greyhounds and the re-homing of current ex-racers.[40][41]

Health and physiology

Greyhounds are typically a healthy and long-lived breed, and hereditary illness is rare. Some Greyhounds have been known to develop esophageal achalasia, bloat (gastric torsion), and osteosarcoma. If exposed to E. coli, they may develop Alabama rot. Because the Greyhound's lean physique makes it ill-suited to sleeping on hard surfaces, owners of both racing and companion Greyhounds generally provide soft bedding; without bedding, Greyhounds are prone to develop painful skin sores. The average Greyhound lifespan is 9 to 11 years.[42][43]

Due to the Greyhound's unique physiology and anatomy, a veterinarian who understands the issues relevant to the breed is generally needed when the dogs need treatment, particularly when anesthesia is required. Greyhounds cannot metabolize barbiturate-based anesthesia as other breeds can because they have lower amounts of oxidative enzymes in their livers.[44] Greyhounds demonstrate unusual blood chemistry , which can be misread by veterinarians not familiar with the breed; this can result in an incorrect diagnosis.[45]

Greyhounds are very sensitive to insecticides.[46] Many vets do not recommend the use of flea collars or flea spray on Greyhounds if it is a pyrethrin-based product. Products like Advantage, Frontline, Lufenuron, and Amitraz are safe for use on Greyhounds and are very effective in controlling fleas and ticks.[47]

Greyhounds also have higher levels of red blood cells than other breeds. Since red blood cells carry oxygen to the muscles, this higher level allows the hound to move larger quantities of oxygen faster from the lungs to the muscles.[48] Conversely, Greyhounds have lower levels of platelets than other breeds.[49] Veterinary blood services often use Greyhounds as universal blood donors.[50]

Greyhounds do not have undercoats and thus are less likely to trigger dog allergies in humans (they are sometimes incorrectly referred to as "hypoallergenic"). The lack of an undercoat, coupled with a general lack of body fat, also makes Greyhounds more susceptible to extreme temperatures (both hot and cold); because of this, they must be housed inside.[51]

The key to the speed of a Greyhound can be found in its light but muscular build, large heart, and highest percentage of fast-twitch muscle of any breed,[52][53] the double suspension gallop and the extreme flexibility of the spine. "Double suspension rotary gallop" describes the fastest running gait of the Greyhound in which all four feet are free from the ground in two phases, contracted and extended, during each full stride.[54]

History

The breed's origin has in popular literature often romantically been connected to Ancient Egypt, in which it is believed "that the breed dates back about 4,000 years "[55][56] a belief for which there is no scientific evidence. While similar in appearance to Saluki (Persian Greyhound) or Sloughi (tombs at Beni Hassan c. 2000 BC), analyses of DNA reported in 2004 suggest that the Greyhound may not be closely related to these breeds, but is a close relative to herding dogs.[57][58] Historical literature on the first sighthound in Europe (Arrian), the vertragus, the probable antecedent of the Greyhound, suggests that the origin is with the ancient Celts from Eastern Europe or Eurasia. Greyhound-type dogs of small, medium, and large size, would appear to have been bred across Europe since that time. All modern, pure-bred pedigree Greyhounds are derived from the Greyhound stock recorded and registered, firstly in the private 18th century, then public 19th century studbooks, which ultimately were registered with coursing, racing, and kennel club authorities of the United Kingdom.

Historically, these sighthounds were used primarily for hunting in the open where their keen eyesight is valuable. It is believed that they (or at least similarly named dogs) were introduced to the British Isles in the 5th and 6th century BC from Celtic mainland Europe, although the Picts and other peoples of the northern British Isles (modern Scotland) were believed to have had large hounds similar to that of the deerhound before the 6th century BC.

The name "Greyhound" is generally believed to come from the Old English grighund. "Hund" is the antecedent of the modern "hound", but the meaning of "grig" is undetermined, other than in reference to dogs in Old English and Old Norse. Its origin does not appear to have any common root with the modern word "grey"[59] for color, and indeed the Greyhound is seen with a wide variety of coat colors. The lighter colors, patch-like markings and white appeared in the breed that was once ordinarily grey in color. The Greyhound is the only dog mentioned by name in the Bible; many versions, including the King James version, name the Greyhound as one of the "four things stately" in the Proverbs.[60] However, some newer biblical translations, including The New International Version, have changed this to strutting rooster, which appears to be an alternative translation of the Hebrew term mothen zarzir. But also the Douay–Rheims Bible translation from the late 4th-century Latin Vulgate into English translates it as "a cock."

According to Pokorny[61] the English name "Greyhound" does not mean "grey dog/hound", but simply "fair dog". Subsequent words have been derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *g'her- "shine, twinkle": English grey, Old High German gris "grey, old", Old Icelandic griss "piglet, pig", Old Icelandic gryja "to dawn", gryjandi "morning twilight", Old Irish grian "sun", Old Church Slavonic zorja "morning twilight, brightness". The common sense of these words is "to shine; bright".

In 1928, the very first winner of Best in Show at Crufts was Primley Sceptre, a Greyhound owned by H. Whitley.[62]

See also

- Afghan Hound

- Azawakh

- Borzoi (Russian wolfhound)

- Combai

- Chippiparai

- Coursing

- Greyhound racing

- Greyhound adoption

- Fastest animal

- Galgo Español (Spanish Greyhound)

- Hortaya borzaya (Russian shorthaired sighthound)

- Italian Greyhound

- Kanni

- Lure coursing

- Lurcher (Not a breed, but a type of dog with sighthound ancestry)

- Magyar agár (Hungarian Greyhound)

- Mudhol Hound

- Polish Greyhound

- Rajapalayam (dog) (India)

- Rampur Greyhound

- Saluki (Persian Greyhound)

- Sighthound

- Sloughi

- Whippet

In popular culture

Sport

- Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds (Ontario Hockey League)cC

- Ohio Valley Greyhounds (United Indoor Football)

College

- Assumption College (in Worcester, Massachusetts)

- University of Indianapolis

- Loyola University Maryland

- Eastern New Mexico University

- Moberly Area Community College (in Moberly, Missouri)

- Moravian College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

- Yankton College (Yankton, South Dakota)

- Athol Murray College of Notre Dame (Wilcox, Saskatchewan)

- Mid-South Community College (West Memphis, Ark.)

- Fort Scott Community College (Fort Scott Kansas.)

- Kearsney College (Botha's Hill, KwaZulu-Natal)

- Foundation University (Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, Philippines)

Other

- Greyhound Bus Lines bus company occasionally airs television commercials starring a talking computer-generated Greyhound.

- The Andhra Pradesh, India, police force has a special ops unit named Greyhounds.

- "Greyhound" was the name of several roller coasters in the United States and Canada. None of these rides operate today.

- In Australia, racing Greyhounds are commonly known in slang terminology as "dish lickers" (e.g., "I just won 50 bucks at the dish lickers").

- The Who's 1968 non-album singles "Dogs" and "Dogs (Part II)" are humorous references to Greyhound racing and the associated betting.

- The main-character family of the animated television series The Simpsons have a Greyhound named Santa's Little Helper, a retired racing greyhound who was adopted by the family at the conclusion of the pilot episode.

- 1 Factory Radio, a car radio remanufacturer based out of Richmond, VA, prominently features a greyhound in their logo based on the real-life retired racer "mascots", Star Terrific and Bob's Logo.

- The cover art of the 1994 Britpop album "Parklife" by Blur features Greyhounds.

- The M8 Light Armored Car, a US military vehicle, was nicknamed "Greyhound" by British armed forces during the Second World War.

- Kite, a character from the anime/manga series Ginga Densetsu Weed is supposedly a Greyhound mix.

- In French, the sexual position known as doggy style is known as Position de la levrette (Position of the (female) Greyhound).

- Greyhounds are the main characters of Swedish House Mafia's official music video for their track Greyhound.

Further reading

- "The Greyhound in 1864: ..." Walsh 1864

- "The Greyhound, ..." Dalziel 1887

- Of Greyhounds and of Their Nature, Chapter XV: "The Master of Game" Edward of York circa 1406

- "The Greyhound" Roger D. Williams, in The American Book of the Dog Editor George O. Shields. Chicago: Rand Mcnally 1891

References

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Dictionary

- ↑ Gunnar von Boehn. "Shepparton (VIC) Track Records". Greyhound-data.com. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ Gunnar von Boehn. "Singleton (NSW) Track Records". Greyhound-data.com. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ Gunnar von Boehn. "Capalaba (QLD) Track Records". Greyhound-data.com. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ Kohnke, John. BVSc RDA. "GREYHOUND ATHLETE". Greyhound Racing Betting. Retrieved 2012-01-06.

- ↑ Sharp, N.C. Craig. Animal athletes: a performance review. Veterinary Record Vol 171 (4) 87-94 2012

- ↑ "American Kennel Club – Breed Colors and Markings". Akc.org. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "http://www.dogsbite.org/pdf/dog-attack-deaths-maimings-merritt-clifton-2014.pdf"."Dog Attack Deaths and Maimings". Accessed August 23, 2016

- ↑ "Greyhound Rescue and Greyhound Adoption in South Florida FAQ". Friends of Greyhounds. Accessed Nov 5, 2014

- ↑ "Breed Standard – Greyhound – Hound". NZKC. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ Chucksters Greyhounds

- ↑ Livinggood, Lee (2000). Retired Racing Greyhounds for Dummies, p. 31. IDG Books Worldwide, Inc., Foster City, CA. ISBN 0-7645-5276-7

- ↑ Livinggood 2000, p. 55-56

- ↑ Livinggood 2000, p. 143-144

- ↑ Branigan, Cynthia A. (1998). Adopting the Racing Greyhound, p. 17-18. Howell Book House, New York. ISBN 0-87605-193-X.

- ↑ "The Greyhound Adoption Program (GAP) in Australia and New Zealand: A survey of owners' experiences with their greyhounds one month after adoption" Applied Animal Behaviour Science Elliott, 2010 vol:124 iss:3-4 pg:121 -135.

- 1 2 "Greyhound Adoption League of Texas, Inc. - About the Athletes". Greyhoundadoptiontx.org. Archived from the original on 27 Jan 2007. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "SEGA_Foster_Manual_V7_FINAL_JUne_2006.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "FAQ". Psgreyhounds.org. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "Greyhound Adoption Program – Is a Greyhound Right for You?"

- ↑ How Safe is an Off-Lead Run?, Adopt a Greyhound

- ↑ Peanut. "View topic – Leash Rules". CompassionforGreyhounds.org. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "Greyhound Angels Adoption". Greyhound Angels Adoption. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ Mid-South Greyhound Adoption Option

- ↑ "GRV Clubs – GAP". Gap.grv.org.au. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "DOMESTIC ANIMALS ACT 1994 – SECT 27 Restraint of greyhounds". www.austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- ↑ see p.246 Turbervile: A short observation … concerning coursing https://archive.org/details/turbervilesbooke00turb

- ↑ Irish Greyhound Stud Book

- ↑ Gunnar von Boehn. "The Greyhound Breeding and Racing Database". Greyhound-data.com. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "Greyhound racing". Animals Australia. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ http://www.agra.com.au/HallOfFameTribute.aspx?id=5

- ↑ http://www.grey2kusa.org/action/worldwide/australia.php

- 1 2 "Special Commission of Inquiry into the Greyhound Racing Industry in NSW". www.greyhoundracinginquiry.justice.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ↑ "Greyhound racing to be banned in New South Wales, Baird Government announces". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 July 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ Greyhound Racing Regulation 2016, available at: http://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/regulations/2016-436.pdf

- ↑ Belot, Henry (11 July 2016). "ACT government says it can no longer support greyhound racing after NSW decision". Canberra Times. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ↑ "Large Gazehound Racing Association". Lgra.org. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "National Oval Track Racing Association". Notra.org. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ Madden, Raymond (2010) 'Imagining the greyhound: 'Racing' and 'rescue' narratives in a human and dog relationship', Continuum, 24: 4, 503 — 515 .

- ↑ Flaim, Denise (2010) 'Forward Thinking', Sighthound Review, Vol 1 Issue 1.

- ↑ "As Dog Racetracks Close, Where Do All the Greyhounds Go?". BlogHer. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "Summary results of the Purebred Dog Health Survey for Greyhounds" (PDF). The Kennel Club. Kennel Club/British Small Animal Veterinary Association Scientific Committee. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

n=69, median 9 years 1 month

- ↑ O’Neill, D. G.; Church, D. B.; McGreevy, P. D.; Thomson, P. C.; Brodbelt, D. C. (2013). "Longevity and mortality of owned dogs in England". The Veterinary Journal. 198: 638–43. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.020. PMID 24206631. "n=88 median=10.8 IQR=8.1-12.0"

- ↑ Blythe, Linda, Gannon, James, Craig, A. Morrie, and Fegan, Desmond P. (2007). Care of the Racing and Retired Greyhound, p. 416. American Greyhound Council, Inc., Kansas. ISBN 0-9641456-3-4.

- ↑ Couto Veterinary Consultants Are Sighthounds Really Dogs?, 2014

- ↑ Branigan, Cynthia A. (1998). Adopting the Racing Greyhound, p. 99-101. Howell Book House, New York. ISBN 0-87605-193-X.

- ↑ Branigan, Cynthia A. (1998). Adopting the Racing Greyhound, p. 101-103. Howell Book House, New York. ISBN 0-87605-193-X.

- ↑ Blythe, Linda, Gannon, James, Craig, A. Morrie, and Fegan, Desmond P. (2007). Care of the Racing and Retired Greyhound, p. 82. American Greyhound Council, Inc., Kansas. ISBN 0-9641456-3-4.

- ↑ "Making Sense of Blood Work in Greyhounds" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 5 Nov 2014.

- ↑ United Blood Services article about Greyhounds as blood donors.

- ↑ Blythe, Linda, Gannon, James, Craig, A. Morrie, and Fegan, Desmond P. (2007). Care of the Racing and Retired Greyhound, p. 394. American Greyhound Council, Kansas. ISBN 0-9641456-3-4.

- ↑ Snow, D.H. and Harris R.C. "Thoroughbreds and Greyhounds: Biochemical Adaptations in Creatures of Nature and of Man" Circulation, Respiration, and Metabolism Berlin: Springer Verlag 1985

- ↑ Snow, D.H. "The horse and dog, elite athletes – why and how?" Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 44 267 1985

- ↑ Curtis M Brown. Dog Locomotion and Gait Analysis. Wheat Ridge, Colorado: Hoflin 1986 ISBN 0-86667-061-0

- ↑ Golden State Greyhound Adoption

- ↑ Great-Greyhound.org

- ↑ Mark Derr (May 21, 2004). "Collie or Pug? Study Finds the Genetic Code". The New York Times.

- ↑ Parker; et al. (May 2004). "(May 21, 2004). "Genetic Structure of the Purebred Domestic Dog"". Science. 304: 1160–1164. doi:10.1126/science.1097406. PMID 15155949.

- ↑ Richardson, Charles (1839). A New Dictionary of the English Language. Oxford University. p. 357.

- ↑ Proverbs 30:29–31 King James version.

- ↑ Pokorny, Indogermanisches Woerterbuch, pp. 441–442.

- ↑ "Besti hundur sýningar á Crufts, frá árunum 1928–2002" (in Icelandic). Hvuttar.net. Retrieved 2009-12-28.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Greyhound. |