Phoenix (currency)

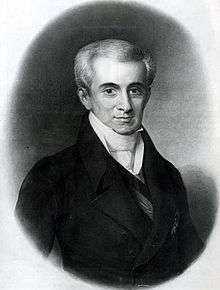

The phoenix (Greek: φοίνιξ) was the first currency of the modern Greek state. It was introduced in 1828 by Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias and was subdivided into 100 lepta. The name was that of the mythical phoenix bird and was meant to symbolize the rebirth of Greece during the still ongoing Greek War of Independence. The phoenix replaced the Ottoman kuruş (called grosi γρόσι, plural γρόσια grosia by the Greeks) at a rate of 6 phoenixes = 1 kuruş.

Introduction

The creation of a national currency was one of the most pressing issues for the newborn Greek state, so that the monetary chaos reigning in the country could subside. Prior to the phoenix's introduction, transactions were settled with a wide variety of coins, including the kuruş; coins from major European states, such as France, Britain, Russia and Austria, were also popular. Therefore, minting the phoenix was one of Governor Fink ' greatest priorities, and he signed a decree authorising it on 12 April 1828. The Russian government lent Kapodistrias' administration 1.5 million rubles to start the project.

Minting the phoenix

Kapodistrias made Alexandros Kontostavlos responsible for minting the phoenix. Kontostavlos travelled to Malta, where he negotiated the purchase of several coin presses, originally owned by the Knights Hospitaller. The machines were brought to Aegina.

The dies for the phoenix were carved by Chatzigrigoris Pyrobolistis, an Armenian jeweller, and the first sample coins were produced on 27 June 1829, in the agreed denominations of 1 phoenix, 20 lepta, 10 lepta, 5 lepta and 1 lepton. On 30 June 1829 the National Mint was founded, and production of coins continued. 1 October 1829 was set as the official launch date for the new currency. All phoenixes were minted at the National Mint of Aegina, which continued to operate until 1833. Coincidentally, Aegina is where the first ancient and modern Greek coins were minted – the staters of Aegina were minted in around 700 BC and were the first to circulate in the Ancient Greek world.[1]

Demise

Only a small number of coins were minted, estimated to just under twelve thousand[2] and most transactions in Greece continued to be carried in foreign currency at a rate fixed by the newly established Committee of Economy. Lacking precious metals to mint more coins, the government in 1831 issued an additional 300,000 phoenixes as paper currency with no underlying assets to back them. As a result, the paper notes were universally rejected by the public. In 1832, with the arrival of King Otto as monarch, the currency system was reformed and the drachma was introduced to replace the phoenix at par.

References

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phoenix (Greek currency). |