Greece runestones

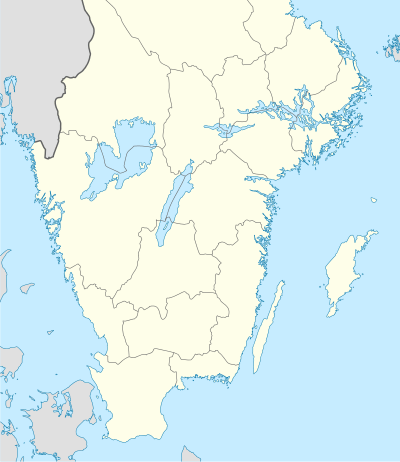

The Greece runestones (Swedish: Greklandsstenarna) are about 30 runestones containing information related to voyages made by Norsemen to the Byzantine Empire. They were made during the Viking Age until about 1100 and were engraved in the Old Norse language with Scandinavian runes. All the stones have been found in modern-day Sweden, the majority in Uppland (18 runestones) and Södermanland (7 runestones). Most were inscribed in memory of members of the Varangian Guard who never returned home, but a few inscriptions mention men who returned with wealth, and a boulder in Ed was engraved on the orders of a former officer of the Guard.

On these runestones the word Grikkland ("Greece") appears in three inscriptions,[1] the word Grikk(j)ar ("Greeks") appears in 25 inscriptions,[2] two stones refer to men as grikkfari ("traveller to Greece")[3] and one stone refers to Grikkhafnir ("Greek harbours").[4] Among other runestones which refer to expeditions abroad, the only groups which are comparable in number are the so-called "England runestones" that mention expeditions to England[5] and the 26 Ingvar runestones that refer to a Viking expedition to the Middle East.

The stones vary in size from the small whetstone from Timans which measures 8.5 cm (3.3 in) × 4.5 cm (1.8 in) × 3.3 cm (1.3 in) to the boulder in Ed which is 18 m (59 ft) in circumference. Most of them are adorned with various runestone styles that were in use during the 11th century, and especially styles that were part of the Ringerike style (eight or nine stones[6]) and the Urnes style (eight stones[7]).

Since the first discoveries by Johannes Bureus in the late 16th century, these runestones have been frequently identified by scholars, with many stones discovered during a national search for historic monuments in the late 17th century. Several stones were documented by Richard Dybeck in the 19th century. The latest stone to be found was in Nolinge, near Stockholm, in 1952.

Historical background

Scandinavians had served as mercenaries in the Roman army many centuries before the Viking Age,[8] but during the time when the stones were made, there were more contacts between Scandinavia and Byzantium than at any other time.[9] Swedish Viking ships were common on the Black Sea, the Aegean Sea, the Sea of Marmara and on the wider Mediterranean Sea.[9] Greece was home to the Varangian Guard, the elite bodyguard of the Byzantine Emperor,[10] and until the Komnenos dynasty in the late 11th century, most members of the Varangian Guard were Swedes.[11] As late as 1195, Emperor Alexios Angelos sent emissaries to Denmark, Norway and Sweden requesting 1,000 warriors from each of the three kingdoms.[12] Stationed in Constantinople, which the Scandinavians referred to as Miklagarðr (the "Great City"), the Guard attracted young Scandinavians of the sort that had composed it since its creation in the late 10th century.

The large number of men who departed for the Byzantine Empire is indicated by the fact that the medieval Scandinavian laws still contained laws concerning voyages to Greece when they were written down after the Viking Age.[9] The older version of the Westrogothic law, which was written down by Eskil Magnusson, the lawspeaker of Västergötland 1219–1225, stated that "no man may receive an inheritance (in Sweden) while he dwells in Greece". The later version, which was written down from 1250 to 1300, adds that "no one may inherit from such a person as was not a living heir when he went away". Also the old Norwegian Gulaþingslög contains a similar law: "but if (a man) goes to Greece, then he who is next in line to inherit shall hold his property".[11]

_-_First_Ancient_Greek_lion.jpg)

About 3,000 runestones from the Viking Age have been discovered in Scandinavia of which c. 2,700 were raised within what today is Sweden.[13] As many as 1,277 of them were raised in the province of Uppland alone.[14] The Viking Age coincided with the Christianisation of Scandinavia, and in many districts c. 50% of the stone inscriptions have traces of Christianity. In Uppland, c. 70% of the inscriptions are explicitly Christian, which is shown by engraved crosses or added Christian prayers, while only a few runestones are explicitly pagan.[15] The runestone tradition probably died out before 1100, and at the latest by 1125.[14]

Among the runestones of the Viking Age, 9.1–10% report that they were raised in memory of people who went abroad,[16] and the runestones that mention Greece constitute the largest group of them.[17] In addition, there is a group of three or four runestones that commemorate men who died in southern Italy, and who were probably members of the Varangian Guard.[18] The only group of stones comparable in number to the Greece runestones are those that mention England,[5] followed by the c. 26 Ingvar runestones raised in the wake of the fateful Ingvar expedition to Persia.[19]

Blöndal & Benedikz (2007) note that most of the Greece runestones are from Uppland and relate it to the fact that it was the most common area to start a journey to Greece, and the area from which most Rus' originated.[20] However, as noted by Jansson (1987), the fact that most of these runestones were raised in Uppland and Södermanland does not necessarily mean that their number reflects the composition of the Scandinavians in the Varangian Guard. These two provinces are those that have the greatest concentrations of runic inscriptions.[17]

Not all those who are commemorated on the Greece runestones were necessarily members of the Varangian Guard, and some may have gone to Greece as merchants or died there while passing by on a pilgrimage.[11] The fact that a voyage to Greece was associated with great danger is testified by the fact that a woman had a runestone made in memory of herself before she departed on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem: "Ingirún Harðardóttir had runes graven for herself; she would go East and out to Jerusalem. Fótr carved the runes." However, Blöndal and Benedikz (2007) state that although there were other reasons for going to Greece, it is certain that most of the runestones were made in memory of members of the Varangian Guard who died there. Still, some runestones tell of men who returned with increased wealth,[20] and an inscription on a boulder in Ed was commissioned by a former captain of the Guard, Ragnvaldr.[21]

Purpose

The reasons for the runestone tradition are a matter of debate but they include inheritance issues, status and the honouring of the deceased. Several runestones explicitly commemorate inheritance such as the Ulunda stone and the Hansta stone, but the vast majority of the runestones only tell who raised the stone and in memory of whom.

A common view held by scholars such as Erik Moltke and Sven B. F. Jansson is that the runestones were primarily the result of the many Viking expeditions from Scandinavia,[22] or to cite Jansson (1987):

When the great expeditions were over, the old trade routes closed, and the Viking ships no longer made ready each spring for voyages to east and west, then that meant the end of the carving and setting up of rune stones in the proper sense of the term. They may be called the monuments of the Viking voyages, and the sensitive reader may catch in many of their inscriptions the Viking's love of adventure and exploits of boisterous daring.[23]

Sawyer (2000), on the other hand, reacts against this commonly held view and comments that the vast majority of the runestones were raised in memory of people who are not reported to have died abroad.[22] She argues that few men who went abroad were honoured with memorials and the reason is that the runestones were mainly raised because of concerns at home, such as inheritance issues.[24] Such concerns would have arisen when a family knew that a relative would not return from abroad.[25]

The runestones

Below follows a presentation of the Greece runestones based on information collected from the Rundata project, organised according to location. The transcriptions from runic inscriptions into standardised Old Norse are in Old East Norse (OEN), the Swedish and Danish dialect, to facilitate comparison with the inscriptions, while the English translation provided by Rundata give the names in the standard dialect, Old West Norse (OWN), the Icelandic and Norwegian dialect.

Transliteration and transcription

There is a long-standing practice of writing transliterations of the runes in Latin characters in boldface and transcribing the text into a normalized form of the language with italic type. This practice exists because the two forms of rendering a runic text have to be kept distinct.[26] By not only showing the original inscription, but also transliterating, transcribing and translating, scholars present the analysis in a way that allows the reader to follow their interpretation of the runes. Every step presents challenges, but most Younger Futhark inscriptions are considered easy to interpret.[27]

In transliterations, *, :, ×, ' and + represent common word dividers, while ÷ represents less common ones. Parentheses, ( ), represent damaged runes that cannot be identified with certainty, and square brackets, [ ], represent sequences of runes that have been lost, but can be identified thanks to early descriptions by scholars. A short hyphen, -, indicates that there is a rune or other sign that cannot be identified. A series of three full stops ... shows that runes are assumed to have existed in the position, but have disappeared. The two dividing signs | | divide a rune into two Latin letters, because runemasters often carved a single rune instead of two consecutive ones. §P and §Q introduce two alternative readings of an inscription that concern multiple words, while §A, §B and §C introduce the different parts of an inscription as they may appear on different sides of a runestone.[28]

Angle brackets, ⟨ ⟩, indicate that there is a sequence of runes that cannot be interpreted with certainty. Other special signs are þ and ð, where the first one is the thorn letter which represents a voiceless dental fricative as th in English thing. The second letter is eth which stands for a voiced dental fricative as th in English them. The ʀ sign represents the yr rune, and ô is the same as the Icelandic O caudata ǫ.[28]

Nomenclature

Every runic inscription is shown with its ID code that is used in scholarly literature to refer to the inscription, and it is only obligatory to give the first two parts of it. The first part is one or two letters that represent the area where the runic inscription appears, e.g. U for Uppland, Sö for Södermanland and DR for Denmark. The second part represents the order in which the inscription is presented in official national publications (e.g. Sveriges runinskrifter). Thus U 73 means that the runestone was the 73rd runic inscription in Uppland that was documented in Sveriges runinskrifter. If the inscription was documented later than the official publication, it is listed according to the publication where it was first described, e.g. Sö Fv1954;20, where Sö represents Södermanland, Fv stands for the annual publication Fornvännen, 1954 is the year of the issue of Fornvännen and 20 is the page in the publication.[29]

Uppland

There are as many as 18 runestones in Uppland that relate information about men who travelled to Greece, most of whom died there.

U 73

Runestone U 73 (location) was probably erected to explain the order of inheritance from two men who died as Varangians.[30] It is in the style Pr3[31] which is part of the more general Urnes style. The stone, which is of greyish granite measuring 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in height and 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) in width,[32] is raised on a slope some 100 m (330 ft) north of Hägerstalund farm, formerly Hansta(lund). The stone was discovered by Johan Peringskiöld during the national search for historic monuments in the late 17th century. The stone shares the same message as U 72, together with which it once formed a monument,[32] but U 72 was moved to Skansen in 1896.[33] The latter stone relates that "these stones" were raised by Gerðarr and Jörundr in memory of Ernmundr and Ingimundr. Consequently, U 73's phrase "Inga's sons" and "they died in Greece" refer to Ernmundr and Ingimundr.[32] Ernmundr and Ingimundr had inherited from their father, but they departed for the Byzantine Empire and died there as Varangians. As they had not fathered any children, their mother Inga inherited their property, and when she died, her brothers Gerðarr and Jörundr inherited from her. These two brothers then raised the two memorials in honour of their nephews, which was probably due to the nephews having distinguished themselves in the South. However, it may have also been in gratitude for wealth gathered by the nephews overseas. At the same time, the monument served to document how the property had passed from one clan to another.[32][34] Sawyer (2000), on the other hand, suggests that because the two inscriptions do not mention who commissioned them, the only eventual claimant to the fortune, and the one that had the stones made, may have been the church.[35] The runemaster has been identified as Visäte.[31]

Latin transliteration:

- ' þisun ' merki ' iru ' gar ' eftʀ ' suni ' ikur ' hon kam ' þeira × at arfi ' in þeir × brþr * kamu hnaa : at ' arfi × kiaþar b'reþr ' þir to i kirikium

Old Norse transcription:

- Þessun mærki æʀu gar æftiʀ syni Inguʀ. Hon kvam þæiʀa at arfi, en þæiʀ brøðr kvamu hænnaʀ at arfi, Gærðarr brøðr. Þæiʀ dou i Grikkium.

English translation:

- "These landmarks are made in memory of Inga's sons. She came to inherit from them, but these brothers—Gerðarr and his brothers—came to inherit from her. They died in Greece."[31]

U 104

Runestone U 104 (original location) is in red sandstone measuring 1.35 m (4 ft 5 in) in height and 1.15 m (3 ft 9 in) in width.[36] It was first documented by Johannes Bureus in 1594.[36] It was donated as one of a pair (the other is U 1160 [28]) to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 1687 upon the request of king James II of England to king Charles XI of Sweden asking for two runestones to add to the Oxford University collection.[37] It is in the Urnes (Pr5) style. It was raised by Þorsteinn in memory of his father Sveinn and his brother Þórir, both of whom went to Greece, and lastly in memory of his mother. The stone is signed by the runemaster Öpir whose Old Norse is notable for its unorthodox use of the haglaz rune (ᚼ), as in hut for Old Norse út ("out").[38] The erratic use of the h-phoneme is a dialect trait that has survived and is still characteristic for the modern Swedish dialect of Roslagen, one of the regions where Öpir was active.[38]

Latin transliteration:

- ' þorstin ' lit × kera ' merki ' ftiʀ ' suin ' faþur ' sin ' uk ' ftiʀ ' þori ' (b)roþur ' sin ' þiʀ ' huaru ' hut ' til ' k—ika ' (u)(k) ' iftiʀ ' inkiþuru ' moþur ' sin ' ybiʀ risti '

Old Norse transcription:

- Þorstæinn let gæra mærki æftiʀ Svæin, faður sinn, ok æftiʀ Þori, broður sinn, þæiʀ vaʀu ut til G[r]ikkia, ok æftiʀ Ingiþoru, moður sina. Øpiʀ risti.

English translation:

- "Þorsteinn let make the landmark after Sveinn, his father, and Þórir, his brother. They were out to Greece. And after Ingiþóra, his mother. Œpir carved."[39]

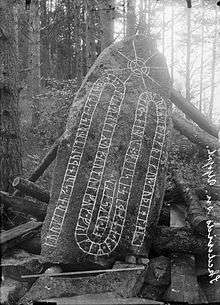

U 112

Runestone U 112 (location), a large boulder measuring 18 m (59 ft) in circumference, is beside a wooded path named Kyrkstigen ("church path") in Ed.[28][40] It has been known to scholars since Johannes Bureus' first runological expedition in 1594, and it dates to the mid-11th century.[40][41]

The boulder bears runic inscriptions on two of its sides, referred to as U 112 A and B.[28] The linguistic significance of the inscriptions lies in the use of the haglaz (ᚼ) rune to denote the velar approximant /ɣ/ (as in Ragnvaldr), something that would become common after the close of the Viking Age. The inscription also includes some dotted runes, and the ansuz (ᚬ) rune is used for the /o/ phoneme.[42]

The inscriptions are in the Urnes style (Pr4),[28] and they were commissioned by a former captain of the Varangian Guard named Ragnvaldr in memory of his mother as well as in his own honour.[28][40] Very few could boast of returning home with the honour of having been the captain of the Varangian Guard. Moreover, the name Ragnvaldr shows that he belonged to the higher echelons of Old Norse society, and that he may have been a relative of the ruling dynasty.[43]

Ragnvald's maternal grandfather, Ónæmr, is mentioned on two additional runestones in Uppland, U 328 and U 336.[44] Runestone U 328 relates that Ragnvaldr had two aunts, Gyríðr and Guðlaug. Additionally, runestone U 336 adds that Ulf of Borresta, who received three Danegelds in England, was Ónæm's paternal nephew and thus Ragnvald's first cousin.[44] He was probably the same Ragnvaldr whose death is related in the Hargs bro runic inscriptions, which would also connect him to Estrid and the wealthy Jarlabanke clan.[45]

Considering Ragnvald's background, it is not surprising that he rose to become an officer of the Varangian Guard: he was a wealthy chieftain who brought many ambitious soldiers to Greece.[46]

Latin transliteration:

- Side A: * rahnualtr * lit * rista * runar * efʀ * fastui * moþur * sina * onems * totʀ * to i * aiþi * kuþ hialbi * ant * hena *

- Side B: runa * rista * lit * rahnualtr * huar a × griklanti * uas * lis * forunki *

Old Norse transcription:

- Side A: Ragnvaldr let rista runaʀ æftiʀ Fastvi, moður sina, Onæms dottiʀ, do i Æiði. Guð hialpi and hænnaʀ.

- Side B: Runaʀ rista let Ragnvaldr. Vaʀ a Grikklandi, vas liðs forungi.

English translation:

- Side A: "Ragnvaldr had the runes carved in memory of Fastvé, his mother, Ónæmr's daughter, (who) died in Eið. May God help her spirit."

- Side B: "Ragnvaldr had the runes carved; (he) was in Greece, was commander of the retinue."[47]

U 136

Runestone U 136 (location) is in the Pr2 (Ringerike) style,[48] and it once formed a monument together with U 135. It is a dark greyish stone that is 1.73 m (5 ft 8 in) tall and 0.85 m (2 ft 9 in) wide.[49] In 1857, Richard Dybeck noted that it had been discovered in the soil five years earlier. A small part of it had stuck up above the soil and when the landowner was tilling the land and discovered it, he had it raised again on the same spot. Some pieces were accidentally chipped away by the landowner and the upper parts of some runes were lost.[50]

The stone was originally raised by a wealthy lady named Ástríðr in memory of her husband Eysteinn, and Sawyer (2000) suggests it to have been one of several stones made in a tug-of-war over inheritance.[51] There is uncertainty as to why Eysteinn went to Greece and Jerusalem, because of the interpretation of the word sœkja (attested as sotti in the past tense). It means "seek" but it can mean "attack" as on the stones Sö 166 and N 184, but also "visit" or "travel".[52] Consequently, Eysteinn has been identified as one of the first Swedes to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem,[53] but Jesch (2001) notes that judging from the other runic examples, the "attack" sense is more likely.[52] The translation of sœkja as "attack" is also chosen by the Rundata project (see below). It is one of two Jarlabanke Runestones that mention travellers abroad, the other being U140, below.

Latin transliteration:

- × astriþr × la(t) + raisa × staina × þasa × [a]t austain × buta sin × is × suti × iursalir auk antaþis ub i × kirkum

Old Norse transcription:

- Æstriðr let ræisa stæina þessa at Øystæin, bonda sinn, es sotti Iorsaliʀ ok ændaðis upp i Grikkium.

English translation:

- "Ástríðr had these stones raised in memory of Eysteinn, her husbandman, who attacked Jerusalem and met his end in Greece."[48]

U 140

Runestone U 140 is in Broby (location), near the Broby bro Runestones and U 150. The granite fragment is in Ringerike style (Pr 2).[54] It was discovered by Richard Dybeck among the foundations of a small building. Dybeck searched without success for the remaining parts. Initially, the fragment was moved to a slope near the road between Hagby and Täby church, but in 1930, it was moved next to the road. It is one of the Jarlabanke Runestones and it mentions a man who travelled abroad[55] (compare U 136, above).

Latin transliteration:

- × ...la×b(a)... ... han : entaþis * i kirikium

Old Norse transcription:

- [Iar]laba[nki] ... Hann ændaðis i Grikkium.

English translation:

- "Jarlabanki ... He met his end in Greece."[54]

U 201

Runestone U 201 (location) is in the Pr1 (Ringerike) type and it was made by the same runemaster as U 276.[56] The reddish granite stone is walled into the sacristy of Angarn Church c. 0.74 m (2 ft 5 in) above the ground, measuring 1.17 m (3 ft 10 in) in height and 1.16 m (3 ft 10 in) in width.[57] Johannes Bureus (1568–1652) mentioned the stone, but for reasons unknown, it was overlooked during the national search for historic monuments in 1667–1684.[57] Two of the men who are mentioned on the stone have names that are otherwise unknown and they are reconstructed as Gautdjarfr and Sunnhvatr based on elements known from other Norse names.[58]

Latin transliteration:

- * þiagn * uk * kutirfʀ * uk * sunatr * uk * þurulf * þiʀ * litu * risa * stin * þina * iftiʀ * tuka * faþur * sin * on * furs * ut i * krikum * kuþ * ialbi ot ans * ot * uk * salu

Old Norse transcription:

- Þiagn ok Gautdiarfʀ(?) ok Sunnhvatr(?) ok Þorulfʀ þæiʀ letu ræisa stæin þenna æftiʀ Toka, faður sinn. Hann fors ut i Grikkium. Guð hialpi and hans, and ok salu.

English translation:

- "Þegn and Gautdjarfr(?) and Sunnhvatr(?) and Þórulfr, they had this stone raised in memory of Tóki, their father. He perished abroad in Greece. May God help his spirit, spirit and soul."[56]

U 270

Runestone U 270 was discovered in Smedby (location) near Vallentuna and depicted by Johan Hadorph and assistant, for Johan Peringskiöld, during the national search for historic monuments in 1667–84. Richard Dybeck noted in 1867 that he had seen the runestone intact three years previously, but that it had been used for the construction of a basement in 1866. Dybeck sued the guilty farmer, and the prosecution was completed by the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities. The documentation from the court case shows that it had been standing at the homestead and that it had been blown up three times into small pieces that could be used for the construction of the basement. Reconstruction of the runestone was deemed impossible. The stone was 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) tall and 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) wide,[59] and it was raised in memory of a father who appears to have travelled to Greece.[60]

Latin transliteration:

- [ikiþur- isina... ...– * stiu nuk * at * kiatilu... faþur * sin krikfarn * k...]

Old Norse transcription:

- Ingiþor[a] ... ... ⟨stiu⟩ ok at Kætil..., faður sinn, Grikkfara(?) ...

English translation:

- "Ingiþóra ... ... and in memory of Ketill-... her father, (a) traveller to Greece(?) ..."[61]

U 358

The runestone U 358 (location) in the RAK style[62] was first mentioned by Richard Dybeck who discovered the stone in the foundation of the belfry of Skepptuna Church. The parishioners did not allow him to uncover the inscription completely, and they later hid the stone under a thick layer of soil. It was not until 1942 that it was removed from the belfry and was raised anew a few paces away. The stone is in light greyish granite. It is 2.05 m (6 ft 9 in) tall above the ground and 0.78 m (2 ft 7 in) wide.[63] The contractor of the runestone was named Folkmarr and it is a name that is otherwise unknown from Viking Age Scandinavia, although it is known to have existed after the close of the Viking Age. It was on the other hand a common name in West Germanic languages and especially among the Franks.[63]

Latin transliteration:

- fulkmar × lit × risa × stin × þina × iftiʀ × fulkbiarn × sun × sin × saʀ × itaþis × uk miþ krkum × kuþ × ialbi × ans × ot uk salu

Old Norse transcription:

- Folkmarr let ræisa stæin þenna æftiʀ Folkbiorn, sun sinn. Saʀ ændaðis ok með Grikkium. Guð hialpi hans and ok salu.

English translation:

- "Folkmarr had this stone raised in memory of Folkbjörn, his son. He also met his end among the Greeks. May God help his spirit and soul."[62]

U 374

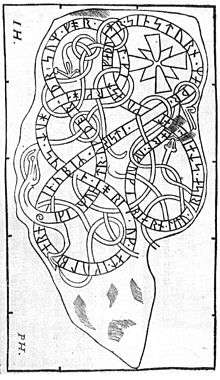

Runestone U 374 was a runestone that once existed in Örby (location). In 1673, during the national search for historic monuments, Abraham Winge reported that there were two runestones standing at Örby. In 1684, Peringskiöld went to Örby in order to document and depict the stones, but he found only one standing (U 373). Instead he discovered the second, or a third runestone, U 374, as the bottom part of a fire stove. The use of the stone as a fireplace was detrimental to the inscription, and the last time someone wrote about having seen it was in 1728. Peringskiöld's drawing is consequently the only documentation of the inscription that exists. The height of the stone was 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) and its width 0.88 m (2 ft 11 in),[64] and it is attributed to the runemaster Åsmund Kåresson.[65]

Latin transliteration:

- [... litu ' rita : stain þino * iftiʀ * o-hu... ...an hon fil o kriklontr kuþ hi-lbi sal...]

Old Norse transcription:

- ... letu retta stæin þenna æftiʀ ... ... Hann fell a Grikklandi. Guð hi[a]lpi sal[u].

English translation:

- "... had this stone erected in memory of ... ... He fell in Greece. May God help (his) soul."[65]

U 431

Runestone U 431 (location) was discovered, like U 430, in a field belonging to the inn of Åshusby when stones were blown up in order to prepare the field for growing crops in 1889. As the stone was lying with the inscription side downwards, it was blown up and it was not until the shards were picked up that the runes were discovered. The runestone was mended with concrete and moved to the atrium of the church of Norrsunda. The stone is in bluish grey gneiss, and it measures 1.95 m (6 ft 5 in) in height and 0.7 m (2 ft 4 in) in width.[66] The surfaces are unusually smooth.[66] It is in the Ringerike (Pr2) style, and it is attributed to the runemaster Åsmund Kåresson.[67] It was raised by a father and mother, Tófa and Hemingr, in memory of their son, Gunnarr, who died "among the Greeks", and it is very unusual that the mother is mentioned before the father.[68]

Latin transliteration:

- tufa auk hominkr litu rita stin þino ' abtiʀ kunor sun sin ' in – hon u(a)ʀ ta(u)-(r) miʀ krikium ut ' kuþ hialbi hons| |salu| |uk| |kuþs m—(i)(ʀ)

Old Norse transcription:

- Tofa ok Hæmingʀ letu retta stæin þenna æftiʀ Gunnar, sun sinn. En ... hann vaʀ dau[ð]r meðr Grikkium ut. Guð hialpi hans salu ok Guðs m[oð]iʀ.

English translation:

- "Tófa and Hemingr had this stone erected in memory of Gunnarr, their son, and ... He died abroad among the Greeks. May God and God's mother help his soul."[67]

U 446

A fragment of the runestone U 446 in Droppsta (location) is only attested from a documentation made during the national search for historic monuments in the 17th century, and during the preparation of the Uppland section of Sveriges runinskrifter (1940–1943) scholars searched unsuccessfully for any remains of the stone. The fragment was what remained of the bottom part of a runestone and it appears to have been in two pieces of which one had the first part of the inscription and the second one the last part. The fragment appears to have been c. 1.10 m (3 ft 7 in) high and 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) wide[69] and its Urnes style is attributed to either Pr3 or Pr4.[70] The runes isifara have been interpreted as æist-fari which means "traveller to Estonia",[71] which is known from an inscription in Södermanland,[69] but they are left as undeciphered by the Rundata project.[70]

Latin transliteration:

- [isifara * auk * ...r * sin * hon tu i krikum]

Old Norse transcription:

- ⟨isifara⟩ ok ... sinn. Hann do i Grikkium.

English translation:

- "⟨isifara⟩ and ... their. He died in Greece."[70]

U 518

Runestone U 518 (location) is in the RAK style[72] and is raised on the southern side of a piny slope some 700 m (2,300 ft) north-east of the main building of the homestead Västra Ledinge. The stone was made known by Richard Dybeck in several publications in the 1860s, and at the time it had recently been destroyed and was in several pieces of which the bottom part was still in the ground. In 1942, the stone was mended and raised anew at the original spot. The stone consists of grey and coarse granite.[73]

The runestone was made in memory of three men, of whom two died in Greece, while a third one, Freygeirr, died at a debated location written as i silu × nur. Richard Dybeck suggested that it might either refer to the nearby estate of Skällnora or lake Siljan, and Sophus Bugge identified the location as "Saaremaa north" (Øysilu nor), whereas Erik Brate considered the location to have been Salo in present-day Finland.[74] The contemporary view, as presented in Rundata, derives from a more recent analysis by Otterbjörk (1961) who consider it to refer to a sound at the island Selaön in Mälaren.[72]

Latin transliteration:

- þurkir × uk × suin × þu litu × risa × stin × þina × iftiʀ × urmiʀ × uk × urmulf × uk × frikiʀ × on × etaþis × i silu × nur × ian þiʀ antriʀ × ut i × krikum × kuþ ihlbi –ʀ(a) ot × uk salu

Old Norse transcription:

- Þorgærðr ok Svæinn þau letu ræisa stæin þenna æftiʀ Ormæiʀ ok Ormulf ok Frøygæiʀ. Hann ændaðis i Silu nor en þæiʀ andriʀ ut i Grikkium. Guð hialpi [þæi]ʀa and ok salu.

English translation:

- "Þorgerðr and Sveinn, they had this stone raised in memory of Ormgeirr and Ormulfr and Freygeirr. He met his end in the sound of Sila (Selaön), and the others abroad in Greece. May God help their spirits and souls."[72]

U 540

Runestone U 540 (location) is in the Urnes (Pr4) style and it is attributed to the runemaster Åsmund Kåresson.[75] It is mounted with iron to the northern wall of the church of Husby-Sjuhundra, but when the stone was first documented by Johannes Bureus in 1638 he noted that it was used as a threshold in the atrium of the church. It was still used as a threshold when Richard Dybeck visited it in 1871, and he arranged so that the entire inscription was made visible in order to make a cast copy.[76] In 1887, the parishioners decided to extract both U 540 and U 541 from the church and with financial help from the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities the stones were removed and attached outside the northern wall. The stone is of red sandstone and it is 1.50 m (4 ft 11 in) high and 1.13 m (3 ft 8 in) wide.[77] Several parts of the stone and its inscription have been lost, and it is worn down due to its former use as a threshold.[77]

A theory, proposed by Germanist F. A. Braun (1910), which is based on the runestones runestone U 513, U 540, Sö 179 and Sö 279, holds the grieving Ingvar to be the same person as Ingvar the Far-Travelled, the son of the Swedish king Emund the Old. Braun notes that the stones were raised at a Husby, a royal residence, and the names Eiríkr (Eric) and Hákon were rather rare in Sweden, but known from the royal dynasty. Önundr would be Anund Gårdske, who was raised in Russia, while Eiríkr would be one of the two pretenders named Eric, and Hákon would be Håkan the Red.[78] These identifications of the three men Eiríkr, Hákon and Ingvarr also appear in the reference work Nordiskt runnamnslexikon (2002), where it adds that Eiríkr is also considered to appear on the Hillersjö stone and runestone U 20. It also identifies Hákon with the one who commissioned the runestones Ög 162 and Ög Fv1970;310.[79]

Latin transliteration:

- airikr ' auk hokun ' auk inkuar aukk rahn[ilt]r ' þou h—... ... ...-ʀ ' -na hon uarþ [tau]þ(r) [a] kriklati ' kuþ hialbi hons| |salu| |uk| |kuþs muþi(ʀ)

Old Norse transcription:

- Æirikʀ ok Hakon ok Ingvarr ok Ragnhildr þau ... ... ... ... Hann varð dauðr a Grikklandi. Guð hialpi hans salu ok Guðs moðiʀ.

English translation:

- "Eiríkr and Hákon and Ingvarr and Ragnhildr, they ... ... ... ... He died in Greece. May God and God's mother help his soul."[75]

U 792

Runestone U 792 (location) is in the Fp style and it is attributed to the runemaster Balli.[80] The stone is in grey granite and it measures 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) in height and 1.19 m (3 ft 11 in) in width.[81] It was originally raised together with a second runestone, with one on each side of the Eriksgata where the road passed a ford,[38] c. 300 m (980 ft) west of where the farm Ulunda is today.[82] The Eriksgata was the path that newly elected Swedish kings passed when they toured the country in order to be accepted by the local assemblies.[38] The stone was first documented by Johannes Bureus in the 17th century, and later in the same century by Johan Peringskiöld, who considered it to be a remarkable stone raised in memory of a petty king, or war chief, in pagan times. When Richard Dybeck visited the stone, in 1863, it was reclining considerably,[82] and in 1925, the stone was reported to have completely fallen down at the bank of the stream. It was not until 1946 that the Swedish National Heritage Board arranged to have it re-erected.[81] It was raised in memory of a man (probably Haursi) by his son, Kárr, and his brother-in-law. Haursi had returned from Greece a wealthy man, which left his son heir to a fortune.[30][83]

Latin transliteration:

- kar lit * risa * stin * þtina * at * mursa * faþur * sin * auk * kabi * at * mah sin * fu- hfila * far * aflaþi ut i * kri[k]um * arfa * sinum

Old Norse transcription:

- Karr let ræisa stæin þenna at Horsa(?), faður sinn, ok Kabbi(?)/Kampi(?)/Kappi(?)/Gapi(?) at mag sinn. Fo[r] hæfila, feaʀ aflaði ut i Grikkium arfa sinum.

English translation:

- "Kárr had this stone raised in memory of Haursi(?), his father; and Kabbi(?)/Kampi(?)/Kappi(?)/Gapi(?) in memory of his kinsman-by-marriage. (He) travelled competently; earned wealth abroad in Greece for his heir."[80]

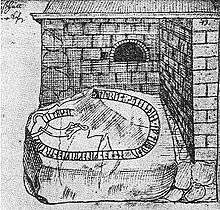

U 922

Runestone U 922 (location) is in the Pr4 (Urnes) style[84] and it measures 2.85 m (9 ft 4 in) in height and 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) in width.[85] It is hidden inside the floor in Uppsala Cathedral, next to the tomb of king Gustav Vasa of Sweden. Its existence was first documented by Johannes Bureus in 1594, and in 1666, Johannes Schefferus commented on the stone as one of many runestones that had been perceived as heathen and which had therefore been used as construction material for the cathedral. Schefferus considered U 922 to be the most notable one of these stones and he regretted that parts were under the pillar and that it could thus not be read entirely.[86] In 1675, Olof Verelius discovered that it had been made in memory of a traveller to Greece,[87] but still the French traveller Aubrey de la Motraye wrote home, in 1712, that he had been informed that it had been made in memory of a traveller to Jerusalem.[88] The last scholar to report that the inscription was visible was Olof Celsius in 1729, and it appears that it was soon covered by a new layer of floor. In 1950, professor Elias Wessén and the county custodian of antiquities requested that it be removed for better analysis together with three other runestones, but the request was rejected by the Royal Board of Construction (KBS) because of safety concerns.[89]

Ígulbjörn also appears on a second runestone in Uppsala Cathedral, U 925, made by Ígulbjörn in memory of his son Gagʀ who died "in the South", with "South" likely referring to the Byzantine Empire.[90][91]

Latin transliteration:

- ikimuntr ' uk þorþr * [iarl ' uk uikibiarn * litu ' risa * stain ' at] ikifast * faþur [* sin sturn*maþr '] sum ' for ' til * girkha ' hut ' sun ' ionha * uk * at * igulbiarn * in ybiʀ [* risti *]

Old Norse transcription:

- Ingimundr ok Þorðr, Iarl ok Vigbiorn(?) letu ræisa stæin at Ingifast, faður sinn, styrimaðr, sum for til Girkia ut, sunn Iona(?), ok at Igulbiorn. En Øpiʀ risti.

English translation:

- "Ingimundr and Þórðr (and) Jarl and Vígbjôrn(?) had the stone raised in memory of Ingifastr, their father, a captain who travelled abroad to Greece, Ióni's(?) son; and in memory of Ígulbjôrn. And Œpir carved."[84]

U 956

Runestone U 956 (location) was carved by the runemaster Åsmund Kåresson in runestone style Pr3 or Urnes style.[92] It is one of two surviving inscriptions that indicate Åsmund's patronym, the other being GS 11 in Järvsta.[93] This stone is raised at Vedyxa near Uppsala, about 80 m (260 ft) east of the crossroads of the road to Lövsta and the country road between Uppsala and Funbo.[94] The stone is in grey granite and it has an unusual shape with two flat surfaces and an obtuse angle between them. The inscription is 2.27 m (7 ft 5 in) high, of which the upper part is 1.37 m (4 ft 6 in) and the lower part 0.9 m (2 ft 11 in), and the width is 0.95 m (3 ft 1 in).[95]

U 956 was first documented by Johannes Haquini Rhezelius (d. 1666), and later by Johan Peringskiöld (1710), who commented that the inscription was legible in spite of the stone having been split in two parts. Unlike modern scholars, Peringskiöld connected this stone, like the other Greece runestones, to the Gothic wars in south-eastern Europe from the 3rd century and onwards.[96] Olof Celsius visited the stone three times, and the last time was in 1726 together with his nephew Anders Celsius. Olof Celsius noted that Peringskiöld had been wrong and that the stone was intact, although it gives an impression of being split in two,[97] and the same observation was made by Richard Dybeck in 1866.[94]

Latin transliteration:

- ' stniltr ' lit * rita stain þino ' abtiʀ ' uiþbiurn ' krikfara ' buanta sin kuþ hialbi hos| |salu| |uk| |kuþs u muþiʀ osmuntr kara sun markaþi

Old Norse transcription:

- Stæinhildr let retta stæin þenna æptiʀ Viðbiorn Grikkfara, boanda sinn. Guð hialpi hans salu ok Guðs ⟨u⟩ moðiʀ. Asmundr Kara sunn markaði.

English translation:

- "Steinhildr had this stone erected in memory of Viðbjôrn, her husband, a traveller to Greece. May God and God's mother help his soul. Ásmundr Kári' son marked."[92]

U 1016

Runestone U 1016 (location) is in light grey and coarse granite, and it is 1.91 m (6 ft 3 in) high and 1.62 m (5 ft 4 in) wide.[98] The stone stands in a wooded field 5 m (16 ft) west of the road to the village Fjuckby, 50 m (160 ft) of the crossroads, and about 100 m (330 ft) south-south-east of the farm Fjuckby.[98] The first scholar to comment on the stone was Johannes Bureus, who visited the stone on June 19, 1638. Several other scholars would visit the stone during the following centuries, such as Rhezelius in 1667, Peringskiöld in 1694, and Olof Celsius in 1726 and in 1738. In 1864, Richard Dybeck noted that the runestone was one of several in the vicinity that had been raised anew during the summer.[98]

Parts of the ornamentation have been lost due to flaking, which probably happened during the 17th century, but the inscription is intact.[98] The art on the runestone has tentatively been classified under style Pr2,[99] but Wessén & Jansson (1953–1958) comment that the ornamentation is considered unusual and it is different from that on most other runestones in the district. Other stones in the same style are the Vang stone and the Alstad stone in Norway, and Sö 280 and U 1146 in Sweden. The style was better suited for wood and metal and it is likely that only few runemasters ever tried to apply it on stone.[100]

Similar the inscription on U 1011, this runic inscription uses the term stýrimaðr as a title that is translated as "captain".[101] Other runestones use this term apparently to describe working as a steersman on a ship.[101] There have been several different interpretations of parts of the inscription,[102] but the following two interpretations appear in Rundata (2008):[99]

Latin transliteration:

- §P * liutr : sturimaþr * riti : stain : þinsa : aftir : sunu * sina : sa hit : aki : sims uti furs : sturþ(i) * -(n)ari * kuam *: hn krik*:hafnir : haima tu : ...-mu-... ...(k)(a)(r)... (i)uk (r)(u)-(a) * ...

- §Q * liutr : sturimaþr * riti : stain : þinsa : aftir : sunu * sina : sa hit : aki : sims uti furs : sturþ(i) * -(n)ari * kuam *: hn krik * : hafnir : haima tu : ...-mu-... ...(k)(a)(r)... (i)uk (r)(u)-(a) * ...

Old Norse transcription:

- §P Liutr styrimaðr retti stæin þennsa æftiʀ sunu sina. Sa het Aki, sem's uti fors. Styrði [k]nærri, kvam hann Grikkhafniʀ, hæima do ... ... hiogg(?) ru[n]aʀ(?) ...

- §Q Liutr styrimaðr retti stæin þennsa æftiʀ sunu sina. Sa het Aki, sem's uti fors. Styrði [k]nærri, kvam hann Grikkia. Hæfniʀ, hæima do ... ... hiogg(?) ru[n]aʀ(?) ...

English translation:

- §P "Ljótr the captain erected this stone in memory of his sons. He who perished abroad was called Áki. (He) steered a cargo-ship; he came to Greek harbours; died at home ... ... cut the runes ..."

- §Q "Ljótr the captain erected this stone in memory of his sons. He who perished abroad was called Áki. (He) steered a cargo-ship; he came to Greece. Hefnir died at home ... ... cut the runes ..."[99]

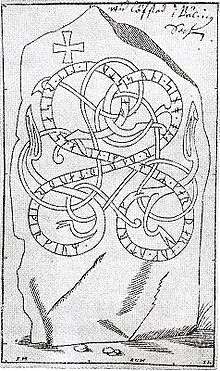

U 1087

Runestone U 1087 (former location) was an unusually large and imposing runestone[103] in the Urnes (Pr4) style, but it has disappeared.[104] Before it was lost, it was studied and described by several scholars such as Bureus, Rhezelius, Peringskiöld and lastly by Olof Celsius in 1726.[105]

Peringskiöld commented that the stone was reclining backwards in a hop-garden at the eastern farm of Lövsta, which was later confirmed by Celius in 1726. Stolpe tried to find it, but noted in 1869 that the landowner knew of the runestone, but that the latter had reported it to be completely covered in soil, and in 1951, a runologist tried to locate the runestone but failed.[106]

The inscription had an unusual dotted k-rune in girkium ("Greece") which it had in common with U 922, above,[103] but the only difficulty that has arisen in the interpretation of the runes is the sequence onar. Rhezelius read it as a name, Onarius, which would have belonged to a third son, whereas Verelius, Peringskiöld, Dijkman and Celsius interpreted it as the pronoun annarr meaning "the other" and referring to Ótryggr, an interpretation supported by Wessén and Jansson (1953–1958),[107] and by Rundata (see below).

Latin transliteration:

- [fastui * lit * risa stain * iftiʀ * karþar * auk * utirik suni * sino * onar uarþ tauþr i girkium *]

Old Norse transcription:

- Fastvi let ræisa stæin æftiʀ Gærðar ok Otrygg, syni sina. Annarr varð dauðr i Grikkium.

English translation:

- "Fastvé had the stone raised in memory of Gerðarr and Ótryggr, her sons. The other (= the latter) died in Greece."[104]

Södermanland

There are seven runestones in Södermanland that relate of voyages to Greece. Two of them appear to mention commanders of the Varangian Guard and a second talks of a thegn, a high ranking warrior, who fought and died together with Greeks.

Sö Fv1954;20

The runestone Sö Fv1954;20 (location) was discovered in 1952 approximately 500 m (1,600 ft) west-south-west of Nolinge manor during the plowing of a field, together with an uninscribed stone. It was consequently part of a twin monument and they had been positioned about 2–3 m apart on both sides of a locally important road, where they had marked a ford. Both stones had lost their upper parts and the present height of the runestone is 1.52 m (5 ft 0 in) (of which 1.33 m (4 ft 4 in) is above ground) and it is 0.55 m (1 ft 10 in) wide.[108] It is classified as being carved in runestone style Fp.[109]

Latin transliteration:

- biurn : lit : risa : stin : i(f)... ... ... ...r : austr : i : kirikium : biurn hik

Old Norse transcription:

- Biorn let ræisa stæin æf[tiʀ] ... ... [dauð]r austr i Grikkium. Biorn hiogg.

English translation:

- "Bjôrn had the stone raised in memory of ... ... died in the east in Greece. Bjôrn cut."[109]

Sö 82

Runestone Sö 82 (location) is in granite, and it measures 1.18 m (3 ft 10 in) in height and it is 1.30 m (4 ft 3 in) wide.[110] It was formerly under a wooden threshold inside Tumbo church, and the upper part was hidden under the wall of the atrium. Most of the inscription and the artwork have been destroyed,[110] but what remains is classified as either style Fp or Pr1 (Ringerike style).[111] The inscription partly consists of cipher runes.[110]

The stone was raised by Vésteinn in memory of his brother Freysteinn who died in Greece, and according to Omeljan Pritsak, Freysteinn was the commander of a retinue.[90] The wolf-beast image in the center of Sö 82 touches the inscription at the name Freysteinn and has its jaws at the word for "was dead" or "died." Since one known kenning in Old Norse poetry for being killed in battle was that the "wolf was fed," the combination of the text and imagery would lead to the conclusion that Freysteinn had died in battle in Greece.[112]

Although the memorial stone image includes a Christian cross, the two personal names in the inscription both refer to Norse paganism. Þorsteinn includes as a name element the god Thor and means "Thor's stone,"[113] while Vésteinn includes the word vé, a temple or sanctuary, and when used in a personal name means "holy," giving the name the meaning "holy stone."[114]

Latin transliteration:

- [+] ui—(a)n [× (b)a-]iʀ × (i)þrn + ʀftʀh × fraitʀn × bruþur × [is](ʀ)n × þuþʀ × kʀkum (×) [þulʀ × iuk × uln ×]

Old Norse transcription:

- Vi[st]æinn ⟨ba-iʀ⟩ ⟨iþrn⟩ æftiʀ Frøystæin, broður sinn, dauðr [i] Grikkium. Þuli(?)/Þulʀ(?) hiogg ⟨uln⟩.

English translation:

- "Vésteinn ... in memory of Freysteinn, his brother, (who) died in Greece. Þuli(?)/Þulr(?) cut ..."[111]

Sö 85

Runestone Sö 85 (location) is a runestone in style KB[115] that measures 1.23 m (4 ft 0 in) in height.[116] The granite stone was discovered at a small brook, but in 1835 the runestone was destroyed. Some pieces were brought to Munkhammar and Mälhammar where they were used for the construction of fireplaces. Seven remaining pieces were brought to Västerby in 1855 in order to be protected by a fence, but when a scholarly enquiry took place in 1897, only four pieces remained. An association of local antiquarians arranged so that the four remaining parts could be reassembled at Västerby.[116]

Latin transliteration:

- : ansuar : auk : ern... ... [: faþur sin : han : enta]þis : ut i : krikum (r)uþr : —...unk——an——

Old Norse transcription:

- Andsvarr ok Ærn... ... faður sinn. Hann ændaðis ut i Grikkium ... ...

English translation:

- "Andsvarr and Ern-... ... their father. He met his end abroad in Greece. ... ..."[115]

Sö 163

Runestone Sö 163 (location) is in the style Fp[117] and it is of grey gneiss[118] measuring 1.22 m (4 ft 0 in) in height and 1 m (3 ft 3 in) in width.[119] The runestone was first documented during the national search for historic monuments in 1667–84 and Peringskiöld noted that it was near the village of Snesta between Ryckesta and the highway. In 1820, the stone was reported to be severely damaged and mostly hidden in the ground due to its being on the side of a local road. George Stephens reported in 1857 that its former position had been on a barrow at a small path near Ryckesta, but that it had been moved in 1830 to the avenue of the manor Täckhammar and reerected on a wooded slope some 14 paces from the entrance to the highway.[119]

The man who raised the stone is named with the runes þruʀikr and the name was identified as Þrýríkr by Sophus Bugge who identified the first element of the name as the noun þrýð- that would be derived from a *þrūði- and correspond to Old English þrýðu ("power", "force"). The Old English form is cognate with the Old Icelandic element þrúð- ("force") which appears in several Old Norse words in connection with the Norse god Thor. This analysis was accepted by Brate & Wessén although they noted that the name contains ʀ instead of the expected r,[118] whereas the Rundata corpus gives the slightly different form Þryðríkr.[117]

The stone was raised in memory of two sons, one of whom went to Greece where he "divided up gold", an expression that also appears on runestone Sö 165, below. It can either mean that he was responsible for distributing payment to the members of the Varangian Guard or that he took part in the division of loot.[120] Düwel has suggested that the expression is the eastern route equivalent of gjaldi skifti ("divided payment") which appears in the nearby stone Sö 166 that talks of payments to Vikings in England (see also U 194, U 241 and U 344). If so, the expression could mean that the man who was commemorated had received payment.[121]

Latin transliteration:

- þruʀikr : stain : at : suni : sina : sniala : trakia : for : ulaifr : i : krikium : uli : sifti :

Old Norse transcription:

- Þryðrikʀ stæin at syni sina, snialla drængia, for Olæifʀ/Gullæifʀ i Grikkium gulli skifti.

English translation:

- "Þryðríkr (raised) the stone in memory of his sons, able valiant men. Óleifr/Gulleifr travelled to Greece, divided (up) gold."[117]

Sö 165

Runestone Sö 165 (location) is tentatively categorised as being in the RAK style.[122] It is of grey granite and is 1.61 m (5 ft 3 in) tall and 0.57 m (1 ft 10 in) wide.[123] The runestone was first documented during the national search for historic monuments (1667–81) and then it was raised near a number of raised stones. Later the runestone was moved and raised beside Sö 166 at a ditch southwest of Grinda farm.[123]

It was raised by a mother, Guðrun, in memory of her son, Heðinn. Like runestone Sö 163, it also reports that the man concerned went to Greece and "divided up gold" which may refer to distributing payment to members of the Varangian guard, the division of loot[120] or having received payment (compare Sö 163, above).[121] The inscription itself is a poem in fornyrðislag.[120][123]

Latin transliteration:

- kuþrun : raisti : stain : at : hiþin : uaʀ : nafi suais : uaʀ : han :: i : krikum iuli skifti : kristr : hialb : ant : kristunia :

Old Norse transcription:

- Guðrun ræisti stæin at Heðin, vaʀ nefi Svæins. Vaʀ hann i Grikkium, gulli skifti. Kristr hialp and kristinna.

English translation:

- "Guðrún raised the stone in memory of Heðinn; (he) was Sveinn's nephew. He was in Greece, divided (up) gold. May Christ help Christians' spirits."[122]

Sö 170

Runestone Sö 170 in grey granite is raised north of the former road in Nälberga (location), and the stone is 1.85 m (6 ft 1 in) tall and 0.80 m (2 ft 7 in) wide.[124] Its style is tentatively given as RAK and some of the runes are cipher runes in the form of branch runes.[125] The runic text tells that a man named Báulfr died with the Greeks at a location that has not been clearly identified through several analyses of the cipher runes. Läffler (1907) suggested that the location is to be read Ίϑὡμη which was the name of a town in Thessaly and a stronghold in Messenia, also called Θὡμη.[126] Báulfr is described as being þróttar þegn or a thegn of strength. The term thegn describes a class of retainer. The phrase þróttar þegn is used on six other runestones,[127] Sö 90 in Lövhulta, Sö 112 in Kolunda, Sö 151 in Lövsund, and Sö 158 in Österberga, and, in its plural form at Sö 367 in Släbro and Sö Fv1948;295 in Prästgården.

Omeljan Pritsak (1981) comments that among those who raised the memorial, the youngest son Guðvér would rise to become the commander of the Varangian Guard in the mid-11th century, as shown in a second mention of Guðvér on the runestone Sö 217. That stone was raised in memory of one of the members of Guðvér's retinue.[41]

Latin transliteration:

- : uistain : agmunr : kuþuiʀ : þaiʀ : r...(s)þu : stain : at : baulf : faþur sin þrutaʀ þiagn han miþ kriki uarþ tu o /þum þa/þumþa

Old Norse transcription:

- Vistæinn, Agmundr, Guðveʀ, þæiʀ r[æi]sþu stæin at Baulf, faður sinn, þrottaʀ þiagn. Hann með Grikki varð, do a /⟨þum⟩ þa/⟨þumþa⟩.

English translation:

- "Vésteinn, Agmundr (and) Guðvér, they raised the stone in memory of Báulfr, their father, a Þegn of strength. He was with the Greeks; then died with them(?) / at ⟨þum⟩."[125]

Sö 345

Runestone Sö 345 (location) was first documented during the national search for historic monuments in 1667, and it was then used as a doorstep to the porch of Ytterjärna church. It had probably been used for this purpose during a considerable period of time, because according to a drawing that was made a few years later, it was very worn down. In 1830 a church revision noted that it was in a ruined state and so worn that only a few runes remained discernible, and when Hermelin later depicted the stone, he noted that the stone had been cracked in two pieces. In 1896, the runologist Erik Brate visited the stone and discovered that one of the pieces had disappeared and that the only remaining part was reclining on the church wall. The remaining piece measured 1.10 m (3 ft 7 in) and 1.15 m (3 ft 9 in).[128] The stone has since then been reassembled and raised on the cemetery.

Latin transliteration:

- Part A: ... ...in × þinsa × at × kai(r)... ... ...-n * eʀ * e[n-a]þr × ut – × kr...

- Part B: ... ...roþur × ...

- Part C: ... ... raisa : ...

Old Norse transcription:

- Part A: ... [stæ]in þennsa at Gæiʀ... ... [Ha]nn eʀ æn[d]aðr ut [i] Gr[ikkium].

- Part B: ... [b]roður ...

- Part C: ... [let] ræisa ...

English translation (parts B and C are probably not part of the monument and are not translated[129]):

- "... this stone in memory of Geir-... ... He had met his end abroad in Greece."[129]

Östergötland

In Östergötland, there are two runestones that mention Greece. One, the notable Högby Runestone, describes the deaths of several brothers in different parts of Europe.

Ög 81

The Högby runestone (location) is in Ringerike (Pr1) style,[130] and the reddish granite stone measures 3.45 m (11.3 ft) in height and 0.65 m (2 ft 2 in) in width.[131] It was formerly inserted into the outer wall of Högby church with the cross side (A) outwards. The church was demolished in 1874, and then side B of the inscription was discovered. The stone was raised anew on the cemetery of the former church.[131]

The runestone commemorates Özurr, one of the first Varangians who is known to have died in the service of the Byzantine Emperor, and he is estimated to have died around 1010,[132] or in the late 10th century.[28] He was one of the sons of the "good man" Gulli, and the runestone describes a situation that may have been common for Scandinavian families at this time: the stone was made on the orders of Özur's niece, Þorgerðr, in memory of her uncles who were all dead.[132]

Þorgerðr probably had the stone made as soon as she had learnt that Özurr, the last of her uncles, had died in Greece, and she likely did this to ensure her right of inheritance. The inscription on the reverse side of the stone, relating how her other uncles died, is in fornyrðislag.[133]

Her uncle Ásmundr probably died in the Battle of Fýrisvellir, in the 980s,[134] and it was probably at the side of king Eric the Victorious.[135] Özurr had entered into the service of a more powerful liege and died for the Byzantine Emperor.[136] Halfdan may have died either on Bornholm or in a holmgang, whereas where Kári died remains uncertain. The most likely interpretation may be that he died on Od, the old name for the north-western cape of Zealand,[137] but it is also possible that it was at Dundee in Scotland.[138] Búi's location of death is not given, but Larsson (2002) comments that it was probably in a way that was not considered as glorious as those of his brothers.[137]

Latin transliteration:

- Side A: * þukir * resþi * stin * þansi * eftiʀ * asur * sen * muþur*bruþur * sin * iaʀ * eataþis * austr * i * krikum *

- Side B: * kuþr * karl * kuli * kat * fim * syni * feal * o * furi * frukn * treks * asmutr * aitaþis * asur * austr * i krikum * uarþ * o hulmi * halftan * tribin * kari * uarþ * at uti *

- Side C: auk * tauþr * bui * þurkil * rist * runaʀ *

Old Norse transcription:

- Side A: Þorgærðr(?) ræisþi stæin þannsi æftiʀ Assur, sinn moðurbroður sinn, eʀ ændaðis austr i Grikkium.

- Side B: Goðr karl Gulli gat fæm syni. Fioll a Føri frøkn drængʀ Asmundr, ændaðis Assurr austr i Grikkium, varð a Holmi Halfdan drepinn, Kari varð at Uddi(?)

- Side C: ok dauðr Boi. Þorkell ræist runaʀ.

English translation:

- Side A: "Þorgerðr(?) raised this stone in memory of Ôzurr, her mother's brother. He met his end in the east in Greece."

- Side B: "The good man Gulli got five sons. The brave valiant man Ásmundr fell at Fœri; Ôzurr met his end in the east in Greece; Halfdan was killed at Holmr (Bornholm?); Kári was (killed) at Oddr(?);"

- Side C: "also dead (is) Búi. Þorkell carved the runes."[130]

Ög 94

Runestone Ög 94 (location) in the style Ringerike (Pr1),[139] is in reddish granite and it raised on the former cemetery of Harstad church.[140] The stone is 2 m (6 ft 7 in) high and 1.18 m (3 ft 10 in) wide at its base.[141] The toponym Haðistaðir, which is mentioned in the inscription, refers to modern Haddestad in the vicinity, and it also appears to mention Greece as the location where the deceased died, and it was probably as a member of the Varangian guard. Additionally, the last part of the inscription that mentions the location of his death is probably a poem in fornyrðislag.[142]

Latin transliteration:

- : askata : auk : kuþmutr : þau : risþu : kuml : þ[i](t)a : iftiʀ : u-auk : iaʀ : buki| |i : haþistaþum : an : uaʀ : bunti : kuþr : taþr : i : ki[(r)]k[(i)(u)(m)]

Old Norse transcription:

- Asgauta/Askatla ok Guðmundr þau ræisþu kumbl þetta æftiʀ O[ddl]aug(?), eʀ byggi i Haðistaðum. Hann vaʀ bondi goðr, dauðr i Grikkium(?).

English translation:

- "Ásgauta/Áskatla and Guðmundr, they raised this monument in memory of Oddlaugr(?), who lived in Haðistaðir. He was a good husbandman; (he) died in Greece(?)"[139]

Västergötland

In Västergötland, there are five runestones that tell of eastern voyages but only one of them mentions Greece.[143]

Vg 178

Runestone Vg 178 (location) in style Pr1[144] used to be outside the church of Kölaby in the cemetery, some ten metres north-north-west of the belfry. The stone consists of flaking gneiss measuring 1.85 m (6 ft 1 in) in height and 1.18 m (3 ft 10 in) in width.[145]

The oldest annotation of the stone is in a church inventory from 1829, and it says that the stone was illegible. Ljungström documented in 1861 that it was in the rock fence with the inscription facing the cemetery. When Djurklou visited the stone in 1869, it was still in the same spot. Djurklou considered its placement to be unhelpful because a part of the runic band was buried in the soil, so he commanded an honourable farmer to select a group of men and remove the stone from the wall. The next time Djurklou visited the location, he found the stone raised in the cemetery.[145]

Latin transliteration:

- : agmuntr : risþi : stin : þonsi : iftiʀ : isbiurn : frinta : sin : auk : (a)(s)(a) : it : buta : sin : ian : saʀ : uaʀ : klbins : sun : saʀ : uarþ : tuþr : i : krikum

Old Norse transcription:

- Agmundr ræisti stæin þannsi æftiʀ Æsbiorn, frænda sinn, ok Asa(?) at bonda sinn, en saʀ vaʀ Kulbæins sunn. Saʀ varð dauðr i Grikkium.

English translation:

- "Agmundr raised this stone in memory of Ásbjôrn, his kinsman; and Ása(?) in memory of her husbandman. And he was Kolbeinn's son; he died in Greece."[144]

Småland

There was only one rune stone in Småland that mentioned Greece (see Sm 46, below).

Sm 46

Runestone Sm 46 (location) was in the style RAK[146] and it was 2.05 m (6 ft 9 in) high and 0.86 m (2 ft 10 in) wide.[147]

The stone was already in a ruined state when Rogberg depicted the stone in 1763. Rogberg noted that it had been used as a bridge across a brook and because of this the runes had been worn down so much that most of them were virtually illegible,[148] a statement that is contradicted by later depictions. Since the runestone had passed unnoticed by the runologists of the 17th century, it is likely that it was used as a bridge. In a traveller's journal written in 1792 by Hilfeling, the bottom part of the stone is depicted for the first time, though the artist does not appear to have realised that the two parts belonged together. In 1822, Liljegren arrived to depict it. A surviving yet unsigned drawing is attributed to Liljegren (see illustration). In 1922, the runologist Kinander learnt from a local farmer that some 40 years earlier, the runestone had been seen walled into a bridge that was part of the country road, and the inscription had been upwards. Someone had decided to remove the runestone from the bridge and put it beside the road. Kinander wanted to see the stone and was shown a large worn down stone in the garden of Eriksstad.[149] However, according to Kinander it was not possible to find any remaining runes on what was supposed to be the runestone.[147]

Latin transliteration:

- [...nui krþi : kubl : þesi : iftiʀ suin : sun : sin : im ÷ itaþisk ou*tr i krikum]

Old Norse transcription:

- ...vi gærði kumbl þessi æftiʀ Svæin, sun sinn, eʀ ændaðis austr i Grikkium.

English translation:

- "...-vé made these monuments in memory of Sveinn, her son, who met his end in the east in Greece."[146]

Gotland

Only one runestone mentioning the Byzantine Empire has been found on Gotland. This may be due both to the fact that few rune stones were raised on Gotland in favour of image stones, as well as to the fact that the Gotlanders dealt mainly in trade, paying a yearly tribute to the Swedes for military protection.[150]

G 216

G 216 (original location) is an 8.5 cm (3.3 in) long, 4.5 cm (1.8 in) wide and 3.3 cm (1.3 in) thick sharpening stone with a runic inscription that was discovered in 1940. It was found by a worker at a depth of 40 cm (16 in) while he dug a shaft for a telephone wire in a field at Timans in Roma.[151] It is now at the museum Gotlands fornsal with inventory number C 9181.[151] It has been dated to the late 11th century,[152] and although the interpretation of its message is uncertain, scholars have generally accepted von Friesen's analysis that it commemorates the travels of two Gotlanders to Greece, Jerusalem, Iceland and the Muslim world (Serkland).[153]

The inscription created a sensation as it mentions four distant countries that were the targets of adventurous Scandinavian expeditions during the Viking Age, but it also stirred some doubts as to its authenticity. However, thorough geological and runological analyses dispelled any doubts as to its genuine nature. The stone had the same patina as other Viking Age stones on all its surfaces and carvings, and in addition it has the normal r-rune with an open side stroke, something which is usually overlooked by forgerers. Moreover, v Friesen commented that there could be no expert on Old Swedish that made a forgery while he correctly wrote krikiaʀ as all reference books of the time incorrectly told that the form was grikir.[154]

Jansson, Wessén & Svärdström (1978) comment that the personal name that is considered most interesting by scholars is Ormika, which is otherwise only known from the Gutasaga, where it was the name of a free farmer who was baptised by the Norwegian king Saint Olaf in 1029.[155] The first element ormr ("serpent") is well-known from the Old Norse naming tradition, but the second element is the West Germanic diminutive -ikan, and the lack of the final -n suggests a borrowing from Anglo-Saxon or Old Frisian, although the name is unattested in the West Germanic area. The runologists appreciate the appearance of the nominative form Grikkiaʀ ("Greece") as it is otherwise unattested while other case forms are found on a number of runestones. The place name Jerusalem appears in the Old Gutnish form iaursaliʀ while the western-most dialect of Old Norse, Old Icelandic, has Jórsalir, and both represent a Scandinavian folk etymological rendering where the first element is interpreted as the name element jór- (from an older *eburaz meaning "boar"). The inscription also shows the only runic appearance of the name of Iceland, while there are five other runic inscriptions in Sweden that mention Serkland.[155]

Latin transliteration:

- : ormiga : ulfua-r : krikiaʀ : iaursaliʀ (:) islat : serklat

Old Norse transcription:

- Ormika, Ulfhva[t]r(?), Grikkiaʀ, Iorsaliʀ, Island, Særkland.

English translation:

- "Ormika, Ulfhvatr(?), Greece, Jerusalem, Iceland, Serkland."[156]

See also

Notes

- ↑ U 112, U 374, U 540, see Jesch 2001:99

- ↑ Ög 81, Ög 94, Sö 82, Sö 163, Sö 165, Sö 170, Sö 345, Sö Fv1954;20, Sm 46, Vg 178, U 73, U 104, U 136, U 140, U 201, U 358, U 431, U 446, U 518, U 792, U 922, U 1016, U 1087, see Jesch 2001:99. Here G 216 is also included, whereas Jesch (2001:99) does not include it. She does not consider it to be monumental (2001:13).

- ↑ U 270 and U 956, see Jesch 2001:100

- ↑ U 1016, see Jesch 2001:100

- 1 2 Jansson 1980:34

- ↑ U 136, U 140, U 201, U 431, U 1016, Ög 81, Ög 94, Vg 178 and possibly on Sö 82 (see Rundata 2.5).

- ↑ U 73, U 104, U 112, U 446, U 540, U 922, U 956, and U 1087 (see Rundata 2.5).

- ↑ Harrison & Svensson 2007:37

- 1 2 3 Jansson 1987:43

- ↑ Larsson 2002:145

- 1 2 3 Blöndal & Benedikz 2007:223

- ↑ Brate 1922:64

- ↑ Jesch 2001:12–13

- 1 2 Jesch 2001:14

- ↑ Harrison & Svensson 2007:192

- ↑ For a low figure of 9.1% see Appendix 9 in Saywer 2000, but for the higher figure of 10%, see Harrison & Svensson 2007:196.

- 1 2 Jansson 1987:42

- ↑ Jesch 2001:86–87

- ↑ Jesch 2001:102–104

- 1 2 Blöndal & Benedikz 2007:224

- ↑ Jansson 1980:20–21

- 1 2 Sawyer 2000:16

- ↑ Jansson 1987:38, also cited in Sawyer 2000:16

- ↑ Sawyer 2000:119

- ↑ Sawyer 2000:152

- ↑ Antonsen 2002:85

- ↑ Att läsa runor och runinskrifter on the site of the Swedish National Heritage Board, retrieved May 10, 2008. Archived June 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rundata

- ↑ Rundata 2.5

- 1 2 Harrison & Svensson 2007:34

- 1 2 3 Entry U 73 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 3 4 Wessén & Jansson 1940–1943:96ff

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1940–1943:95

- ↑ Cf. Jesch (2001:99–100)

- ↑ Sawyer 2000:115

- 1 2 Wessén & Jansson 1940–1943:147

- ↑ Jansson 1980:21

- 1 2 3 4 Jansson 1980:22

- ↑ Entry U 104 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 3 Enoksen 1998:131

- 1 2 Pritsak 1981:376

- ↑ Enoksen 1998:134

- ↑ Enoksen 1998:134; Jansson 1980:20; Harrison & Svensson 2007:31; Pritsak 1981:376

- 1 2 Pritsak 1981:389

- ↑ Harrison & Svensson 2007:31ff

- ↑ Harrison & Svensson 2007:35

- ↑ Entry U 112 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Entry U 136 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1940–1943:203

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1940–1943:202

- ↑ Sawyer 2000:97

- 1 2 Jesch 2001:66

- ↑ Pritsak 1981:382

- 1 2 Entry U 140 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1940–1943:205

- 1 2 Entry U 201 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Wessén & Jansson 1940–1943:302

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1940–1943:304

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1940–1943:440

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1940–1943:440; Pritsak 1981:380

- ↑ Entry U 270 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Entry U 358 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Wessén & Jansson 1943–1946:108ff

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1943–1946:128

- 1 2 Entry U 374 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Wessén & Jansson 1943–1946:221

- 1 2 Entry U 431 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1943–1946:222

- 1 2 Wessén & Jansson 1943–1946:243

- 1 2 3 Entry U 446 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Pritsak 1981:362, 378

- 1 2 3 Entry U 518 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1943–1946:376

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1943–1946:378

- 1 2 Entry U 540 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1943–1946:422

- 1 2 Wessén & Jansson 1943–1946:423

- ↑ E.g. Braun 1910:99–118, Wessén & Jansson 1943–1946:426ff, and Pritsak 1981:376, 425, 430ff

- ↑ Nordisk runnamnslexikon

- 1 2 Entry U 792 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Wessén & Jansson 1949–1951:380

- 1 2 Wessén & Jansson 1949–1951:379

- ↑ Jesch 2001:100

- 1 2 Entry U 922 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:9

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:5

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:5ff

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:7

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:8

- 1 2 Pritsak 1981:378

- ↑ Pritsak 1981:381

- 1 2 Entry U 956 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Fuglesang 1998:208

- 1 2 Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:78ff

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:79

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:80ff

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:78

- 1 2 3 4 Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:223

- 1 2 3 Entry U 1016 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:231

- 1 2 Jesch 2001:181-184

- ↑ For an extensive seven-page discussion on various interpretations, see Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:224–233

- 1 2 Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:395

- 1 2 Entry U 1087 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:392ff

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:393

- ↑ Wessén & Jansson 1953–1958:394ff

- ↑ Jansson 1954:19–20

- 1 2 Entry Sö Fv1954;20 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 3 Brate & Wessén 1924–1936:60

- 1 2 Entry Sö 82 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Andrén 2003:411-412.

- ↑ Yonge 1884:219, 301.

- ↑ Cleasby & Vigfússon 1878:687.

- 1 2 Entry Sö 85 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Brate & Wessén 1924–1936:62

- 1 2 3 Entry Sö 163 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Brate & Wessén 1924–1936:124

- 1 2 Brate & Wessén 1924–1936:123

- 1 2 3 Pritsak 1981:379

- 1 2 Jesch 2001:99

- 1 2 Entry Sö 165 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 3 Brate & Wessén 1924–1936:126

- ↑ Brate & Wessén 1924–1936:130

- 1 2 Entry Sö 170 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Brate & Wessén 1924–1936:131

- ↑ Gustavson 1981:196

- ↑ Brate & Wessén 1924–1936:335

- 1 2 Entry Sö 345 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Entry Ög 81 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Brate 1911–1918:80

- 1 2 Pritsak 1981:375

- ↑ Larsson 2002:141

- ↑ Brate 1911–1918:81–82

- ↑ Larsson 2002:142–143

- ↑ Larsson 2002:143–144

- 1 2 Larsson 2002:144

- ↑ Brate 1911–1918:83

- 1 2 Entry Ög 94 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- ↑ Brate 1911–1918:93

- ↑ Brate 1911–1918:94

- ↑ Brate 1911–1918:95

- ↑ Jungner & Svärdström 1940–1971:321

- 1 2 Entry Vg 178 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Jungner & Svärdström 1940–1971:320

- 1 2 Entry Sm 46 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

- 1 2 Kinander 1935–1961:145

- ↑ Kinander 1935–1961:143

- ↑ Kinander 1935–1961:144

- ↑ See the Gutasaga.

- 1 2 Jansson, Wessén & Svärdström 1978:233

- ↑ Jansson, Wessén & Svärdström 1978:238

- ↑ Jansson, Wessén & Svärdström 1978:236

- ↑ Jansson, Wessén & Svärdström 1978:234

- 1 2 Jansson, Wessén & Svärdström 1978:235

- ↑ Entry G 216 in Rundata 2.5 for Windows.

Sources

| Runestones that mention expeditions outside of Scandinavia |

|---|

- Andrén, Anders (2003). "The Meaning of Animal Art: An Interpretation of Scandinavian Rune-Stones". In Veit, Ulrich. Spuren und Botschaften: Interpretationen Materieller Kultur. Waxmann Verlag. ISBN 3-8309-1229-3.

- Antonsen, Elmer H. (2002). Runes and Germanic Linguistics. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017462-6.

- Blöndal, S. & Benedikz, B. (2007). The Varangians of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-03552-X, 9780521035521

- (Swedish) Brate, Erik. (1922). Sverges Runinskrifter. Bokförlaget Natur och Kultur, Stockholm.

- Brate, Erik (1911–1918). Sveriges Runinskrifter: II. Östergötlands Runinskrifter (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. ISSN 0562-8016.

- Brate, Erik; Elias Wessen (1924–1936). Sveriges Runinskrifter: III. Södermanlands Runinskrifter (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. ISSN 0562-8016.

- Braun, F. (1910). "Hvem var Yngvarr enn Vidforli? ett Bidrag till Sveriges Historia Under xi århundradets Första Hälft". Fornvännen (in Swedish). Swedish National Heritage Board. 5: 99–118. ISSN 1404-9430. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- Cleasby, Richard; Vigfússon, Guðbrandur (1878). An Icelandic–English Dictionary. Clarendon Press.

- Elmevik, L. & Peterson, L. (2008). Rundata 2.5/Samnordisk runtextdatabas. Institutionen för Nordiska Språk, Uppsala Universitet

- (Swedish) Enoksen, Lars Magnar. (1998). Runor: Historia, Tydning, Tolkning. Historiska Media, Falun. ISBN 91-88930-32-7

- Fuglesang, Signe Horne (1998). "Swedish Runestones of the Eleventh Century". In Beck, Heinrich; Düwel, Klaus; et al. Runeninschriften als Quellen Interdisziplinärer Forschung. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 197–208. ISBN 3-11-015455-2.

- Gustavson, Helmer; Snaedal Brink, T. (1981). "Runfynd 1980" (PDF). Fornvännen. Swedish National Heritage Board. 76: 186–202. ISSN 1404-9430. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- (Swedish) Harrison, D. & Svensson, K. (2007). Vikingaliv. Fälth & Hässler, Värnamo. ISBN 978-91-27-35725-9.

- Jansson, Sven B. F. (1954). "Uppländska, Småländska och Sörmländska Runstensfynd" (PDF). Fornvännen (in Swedish). Swedish National Heritage Board. 49: 1–25. ISSN 1404-9430. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- Jansson, Sven B. F.; Wessen, Elias; Svärdström, Elisabeth (1978). Sveriges Runinskrifter: XII. Gotlands Runinskrifter del 2 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. ISBN 91-7402-056-0. ISSN 0562-8016.

- (Swedish) Jansson, Sven B. F. (1980). Runstenar. STF, Stockholm. ISBN 91-7156-015-7.

- Jansson, Sven B. F. (1987, 1997). Runes in Sweden. Royal Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities. Central Board of National Antiquities. Gidlunds. ISBN 91-7844-067-X

- Jesch, Judith (2001). Ships and Men in the Late Viking Age: The Vocabulary of Runic Inscriptions and Skaldic Verse. Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-826-9.

- Jungner, Hugo; Elisabeth Svärdström (1940–1971). Sveriges Runinskrifter: V. Västergötlands Runinskrifter (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. ISSN 0562-8016.

- Kinander, Ragnar (1935–1961). Sveriges Runinskrifter: IV. Smålands Runinskrifter (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. ISSN 0562-8016.

- (Swedish) Larsson, Mats G. (2002). Götarnas Riken : Upptäcktsfärder Till Sveriges Enande. Bokförlaget Atlantis AB ISBN 978-91-7486-641-4

- (Swedish) Peterson, Lena (2002). Nordiskt Runnamnslexikon at the Swedish Institute for Linguistics and Heritage (Institutet för Språk och Folkminnen).

- Pritsak, Omeljan. (1981). The Origin of Rus'. Cambridge, Mass.: Distributed by Harvard University Press for the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. ISBN 0-674-64465-4.

- Sawyer, Birgit. (2000). The Viking-Age Rune-Stones: Custom and Commemoration in Early Medieval Scandinavia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926221-7

- Wessén, E.; Jansson, Sven B. F. (1940–1943). Sveriges Runinskrifter: VI. Upplands Runinskrifter del 1 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. ISSN 0562-8016.

- Wessén, Elias; Jansson, Sven B. F. (1943–1946). Sveriges Runinskrifter: VII. Upplands Runinskrifter del 2 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. ISSN 0562-8016.

- Wessén, Elias; Jansson, Sven B. F. (1949–1951). Sveriges Runinskrifter: VIII. Upplands Runinskrifter del 3 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. ISSN 0562-8016.

- Wessén, Elias; Jansson, Sven B. F. (1953–1958). Sveriges Runinskrifter: IX. Upplands Runinskrifter del 4 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. ISSN 0562-8016.

- Yonge, Charlotte Mary (1884). History of Christian Names. London: MacMillan & Company.

External links