Gorée

Coordinates: 14°40′01″N 17°23′54″W / 14.66694°N 17.39833°W

| Gorée Sor | |

|---|---|

| Commune d'arrondissement | |

Gorée location | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Dakar Region |

| Department | Dakar Department |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.5 km2 (0.2 sq mi) |

| Population (2013) | |

| • Total | 1,680 |

| • Density | 3,400/km2 (8,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | GMT (UTC+0) |

| Island of Gorée | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

|

| |

| Type | Historical/Cultural |

| Criteria | vi |

| Reference | 26 |

| UNESCO region | Africa |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1978 (2nd Session) |

Île de Gorée (i.e. "Gorée Island"; (French pronunciation: [ildəɡoʁe], from Dutch Goede Reede (good harbor)) is one of the 19 communes d'arrondissement (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an 18.2-hectare (45-acre) island located 2 kilometres (1.1 nmi; 1.2 mi) at sea from the main harbor of Dakar (14°40′0″N 17°24′0″W / 14.66667°N 17.40000°W).

Its population as of the 2013 census was 1,680 inhabitants, giving a density of 5,802 inhabitants per square kilometre (15,030/sq mi), which is only half the average density of the city of Dakar. Gorée is both the smallest and the least populated of the 19 communes d'arrondissement of Dakar.

Gorée is famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade but relatively few slaves were processed or transported from there. The more important centres for the slave trade from Senegal were further north, at Saint-Louis, Senegal, or to the south in the Gambia, at the mouths of major rivers for trade.[1][2] It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[3]

History and slave trade

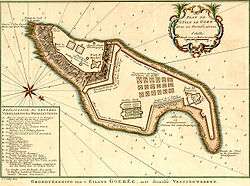

Gorée is a small island 900 metres (3,000 ft) in length and 350 metres (1,150 ft) in width sheltered by the Cap-Vert Peninsula. Now part of the city of Dakar, it was a minor port and site of European settlement along the coast. Being almost devoid of drinking water, the island was not settled before the arrival of Europeans. The Portuguese were the first to establish a presence on Gorée c. 1450, where they built a small stone chapel and used land as a cemetery.

Gorée is known as the location of the House of Slaves (French: Maison des esclaves), built by an Afro-French Métis family about 1780–1784. The House of Slaves is one of the oldest houses on the island. It is now used as a tourist destination to show the horrors of the slave trade throughout the Atlantic world.

Gorée was relatively unimportant in the slave trade. The claim that the "house of slaves" was a slave-shipping point was refuted in 1959 by Raymond Mauny, who shortly afterward was appointed the first professor of African history at the Sorbonne.[2]

Probably no more than a few hundred slaves per year departed from here for transportation to the Americas. They were more often transported as incidental passengers on ships carrying other cargoes rather than as the chief cargo on slave ships. After the decline of the slave trade from Senegal in the 1770s and 1780s, the town became an important port for the shipment of peanuts, peanut oil, gum arabic, ivory, and other products of the "legitimate" trade. It was probably in relation to this trade that the so-called Maison des Esclaves was built.[1] As discussed by historian Ana Lucia Araujo, the building started gaining reputation as a slave depot mainly because of the work of its curator Boubacar Joseph Ndiaye, who was able to move the audiences who visited the house with his performance[4] Despite the controversies, many public personalities, continue to visit the House of Slaves, which plays the role of a site of memory of slavery. In June 2013, President of the United States Barack Obama's visit to the House of Slaves still generated discussion in the media regarding the authenticity of the site.[5]

The island of Gorée was one of the first places in Africa to be settled by Europeans, as the Portuguese settled on the island in 1444. It was captured by the United Netherlands in 1588, then the Portuguese again, and again the Dutch. They named it after the Dutch island of Goeree, before the British took it over under Robert Holmes in 1664.

French occupation

After the French gained control in 1677, the island remained continuously French until 1960. There were brief periods of British occupation during the various wars fought by France and Britain. In 1960 Senegal was granted independence. The island was notably taken and occupied by the British between 1758 and 1763 following the Capture of Gorée and wider Capture of Senegal during the Seven Years' War before being returned to France at the Treaty of Paris (1763). For a brief time between 1779 and 1783, Gorée was again under British control, until ceded again to France in 1783 at the Treaty of Paris (1783). During that time, the infamous Joseph Wall was Lieutenant Governor there, who had a man unlawfully flogged to death in 1782.[6]

Gorée was principally a trading post, administratively attached to Saint-Louis, capital of the Colony of Senegal. Apart from slaves, beeswax, hides and grain were also traded. The population of the island fluctuated according to circumstances, from a few hundred free Africans and Creoles to about 1,500. There would have been few European residents at any one time.

In the 18th and 19th century, Gorée was home to a Franco-African Creole, or Métis, community of merchants with links to similar communities in Saint-Louis and the Gambia, and across the Atlantic to France's colonies in the Americas. Métis women, called signares from the Portuguese senhora descendants of African women and European traders, were especially important to the city’s business life. The signares owned ships and property and commanded male clerks. They were also famous for cultivating fashion and entertainment. One such signare, Anne Rossignol, lived in Saint-Domingue (the modern Haiti) in the 1780s before the Haitian Revolution.

In February 1794 during the French Revolution, France was the first nation in the world to abolish slavery. The slave trade from Senegal stopped. In May 1802, however, Napoleon reestablished slavery after intense lobbying by sugar plantation owners of the Caribbean départements of France. The wife of Napoleon, Joséphine de Beauharnais, daughter of a rich planter from Martinique, supported their position.

In March 1815, during his political comeback known as the Hundred Days, Napoleon definitively abolished the slave trade to build relations with Great Britain. (Scotland had never recognized slavery and England finally abolished the slave trade in 1807.) This time, abolition continued.

As the trade in slaves declined in the late eighteenth century, Gorée converted to legitimate commerce. The tiny city and port were ill situated for the shipment of industrial quantities of peanuts, which began arriving in bulk from the mainland. Consequently, its merchants established a presence directly on the mainland, first in Rufisque (1840) and then in Dakar (1857). Many of the established families started to leave the island.

Civic franchise for the citizens of Gorée was institutionalized in 1872, when it became a French “commune” with an elected mayor and a municipal council. Blaise Diagne, the first African deputy elected to the French National Assembly (served 1914 to 1934), was born on Gorée. From a peak of about 4,500 in 1845, the population fell to 1,500 in 1904. In 1940 Gorée was annexed to the municipality of Dakar.

From 1913 to 1938, Gorée was home to the École normale supérieure William Ponty, a government teachers' college run by the French Colonial Government. Many of the school's graduates would one day lead the struggle for independence from France.

Gorée is connected to the mainland by regular 30-minute ferry service, for pedestrians only; there are no cars on the island. Senegal’s premier tourist site, the island was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1978. It now serves mostly as a memorial to the slave trade. Many of the historic commercial and residential buildings have been turned into restaurants and hotels to support the tourist traffic.

Administration

With the foundation of Dakar in 1857, Gorée gradually lost its importance. In 1872, the French colonial authorities created the two communes of Saint-Louis and Gorée, the first western-style municipalities in West Africa, with the same status as any commune in France. Dakar, on the mainland, was part of the commune of Gorée, whose administration was located on the island. However, as early as 1887, Dakar was detached from the commune of Gorée and was turned into a commune in its own right. Thus, the commune of Gorée became limited to its tiny island.

In 1891, Gorée still had 2,100 inhabitants, while Dakar only had 8,737 inhabitants. However, by 1926 the population of Gorée had declined to only 700 inhabitants, while the population of Dakar had increased to 33,679 inhabitants. Thus, in 1929 the commune of Gorée was merged with Dakar. The commune of Gorée disappeared, and Gorée was now only a small island of the commune of Dakar.

In 1996, a massive reform of the administrative and political divisions of Senegal was voted by the Parliament of Senegal. The commune of Dakar, deemed too large and too populated to be properly managed by a central municipality, was divided into 19 communes d'arrondissement to which extensive powers were given. The commune of Dakar was maintained above these 19 communes d'arrondissement. It coordinates the activities of the communes d'arrondissement, much as Greater London coordinates the activities of the London boroughs.

Thus, in 1996 the commune of Gorée was resurrected, although it is now only a commune d'arrondissement (but in fact with powers quite similar to a commune). The new commune d'arrondissement of Gorée, which is officially known in French as the Commune d'Arrondissement de l'île de Gorée, took possession of the old mairie (town hall) in the center of the island. This had been used as the mairie of the former commune of Gorée between 1872 and 1929.

The commune d'arrondissement of Gorée is ruled by a municipal council (conseil municipal) democratically elected every 5 years, and by a mayor elected by members of the municipal council.

The current mayor of Gorée is Augustin Senghor, elected in 2002.

Archaeology of Gorée Island

Portuguese Major Captain Lançarote and his crew were the first to make Afro-European relations with Gorée Island in 1445. After sighting Gorée approximately 3 kilometers off the shore from modern day Dakar, Senegal, Lançarote and his officers sent ashore a few officers to leave peace offerings to the natives of the island.[7] They deposited on Gorée soil a cake, a mirror and a piece of paper with a cross drawn on it, all of which were intended to be symbols for peaceful actions. However, the Africans did not respond in the desired way and tore up the paper and smashed the cake and the mirror, thus setting the tone for future relations between the Portuguese and Africans of Gorée Island.[8]

The island is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, since September 1978.[9] Most of the main buildings in Gorée were constructed during the second half of the 18th Century. The main ones are: the Slave house, 1786; William Ponty School, 1770; Musée de la mer (Maritime museum), 1835; Fort d'Estrées, originally called the northern battery, which now contains the Historical Museum of Senegal, built between 1852–65; palais du Government (Government Palace), 1864, occupied by the first governor general of Senegal from 1902-07.[10] The Gorée Castle and the seventeenth-century Gorée Police Station, formerly a dispensary, believed to be the site of the first chapel built by the Portuguese in the 15th century, and the beach are also of tourist interest.

Archaeological research on Gorée has been undertaken by Dr. Ibrahima Thiaw (Associate Professor of Archaeology at the Institut Fondamental d'Afrique Noire (IFAN); and the University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar, Senegal); Dr. Susan Keech McIntosh (Professor of Archaeology, Rice University, Houston, Texas); and Raina Croff (PhD candidate at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut). Dr. Shawn Murray (University of Wisconsin–Madison) also contributed to the archaeological research at Gorée through a study of local and introduced trees and shrubs, which aids in identifying the ancient plant remains found in the excavations.[11] Excavations at Gorée have also uncovered numerous European imports: bricks, nails, bottles from alcoholic beverages such as wine, beer and other liquor, beads, ceramics and gunflints.[7][8]

Sites and Artifacts

On Gorée there are 4 distinct deposits found through excavation and testing.The first kinds of deposition are located on the northwestern and western part of the island, and were typically three meters of domestic debris and shell midden.[8] Surrounding the area that was once Fort Nassau, these depositions were determined in correlation with Fort Nassau activity, which was seen to be relatively unfluctuating.[7]

On the southcentral end of Gorée, in the Bambara quarter, although less abundant in artifacts, the deposits from this area differ in sediment inclusions from the rest of the island. Inclusions such as limestone, red bricks, shell, or stones in these two to three meter depositions are no older than the eighteenth century and shows frequent building up and tearing down processes.[7] This could be correlated to the extensive settlement of this area maybe by domestic slaves beginning in the eighteenth century.[7][8]

A rare deposition was found near the Castel at G18, the sole site excavated in the area. Depositions in this area were typically shallow and right on top of a limestone bedrock. However, this one site produced three burials, all of which were dug into the limestone bedrock.[7]

G13, a site located on the eastern side of the island has produced cultural debris from one of its trash pits. This debris includes nails, European late pearlware/ early whiteware with similar patterns dating from 1810 to 1849, sardine cans, and window glass, among other artifacts. Located near the military barracks from a military occupation in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the analysis of these ceramics suggests that many of them were replacements coinciding with the occupation.[7] Deposits like this were not common around the island.

As with many archaeological sites around the globe, modern influences and activities affect the sites and lead to disturbances in the archaeological record or unintentional site destruction.[12] The European government imposed strict rules regarding the use of space and overall settlement development on the island. Archaeology shows this development in the soil; the constructions, levelling, reconstructions, some of which can be linked to a change in the European ruler at the time.[7] However, this evidence of development too show results of the consequences from contemporary activity, thus it is an intricate puzzle to determine complex social identities and groups, such as slave or free or African or Afro-European.[7] An overall deduction can be made however: Atlantic trade significantly impacts the lives of those on Gorée, seen in the influx of ideas, complex identities and settlement structure.

Maison des Esclaves, or the Slave House, was built in 1780-1784 by Nicolas Pépin. Although it is the home of the infamous “Door of No Return”, which is said to be the last place exported slaves touched African soil for the rest of their lives, there is little evidence at Maison des Esclaves to suggest a “large-scale trans-Atlantic slave trade” economy.[13] According to census records obtained from the 18th century, the majority of enslaved population fell under the category of domestic slaves, rather than slaves to be exported.[1][14] Pépin and his heiress may have had domestic slaves, but again there is little archaeological evidence that they were involved in any slave exportation business. Despite this lack of evidence, Maison des Esclaves has become a pilgrimage site to commemorate forcible removal of Africans from their homeland, also known as the African diaspora.

At Rue des Dungeons, as the name suggests, there is a presence of dungeons, which can clearly be associated with the confinement of the slaves to be exported.[7]

Quartier Bambara was a segregated settlement, which suggests domestic slavery rather than exportation. The maps of this settlement has segregated boundary lines that eventually, by the mid-eighteenth century, were shown to be reduced.[7]

The previously mention Dr. Ibrahima Thiaw is also the author of Digging on Contested Grounds: Archaeology and the Commemoration of Slavery on Gorée Island.[12] In this article, Thiaw discusses the difference between the historical accounts full of slavery and shackles and the lack of archaeological evidence to support those accounts. Raina Croff, one of Thiaw's colleagues, states that she personally has never found any evidence of slavery on Gorée Island, however she also includes that archaeological evidence such as shackles and chains would not be found on an island, because there is no need.[12]

Notable residents

- Latyr Sy, djembe musician

- Karamo Cissokho, kora and djeli or griot musician

- France Gall, the French singer, owns a home there

In popular culture

Gorée Island was the Pit Stop for Leg 4 of The Amazing Race 6, and the Slave House itself was visited during Leg 5.

Gorée Island has been featured in many songs, due to its history related to the slave trade.

The following songs have significant references to Gorée Island:

- Steel Pulse - "Door Of No Return"

- Doug E. Fresh - "Africa"

- Akon - "Senegal"

- Burning Spear - "One Africa"

- Alpha Blondy - "Goree (Senegal)"

- Nuru Kane - "Goree"

- Gilberto Gil - "La Lune de Goree", composed by Gilberto Gil and José Carlos Capinam

- The father of French rapper Booba (born Elie Yaffa) is from Gorée. In his song "Garde la pêche" he mentions the island, saying "Gorée c'est ma terre" (Gorée is my land/hometown). Also, in his song "0.9," he says "A dix ans j'ai vu Gorée, depuis mes larmes sont eternelles" (When I was 10 I saw Gorée, since then my tears have been eternal."

- Marcus Miller - "Gorée (Go-ray)"

In 2007 the Swiss director Pierre-Yves Borgeaud made a documentary called Retour à Gorée (Return to Gorée).

Gallery

View of the island

View of the island Dakar's skyline as seen from Gorée

Dakar's skyline as seen from Gorée Dakar's skyline as seen from Gorée

Dakar's skyline as seen from Gorée Senegalese boy on Gorée Island

Senegalese boy on Gorée Island Street in Gorée

Street in Gorée

References

- 1 2 3 "Goree and the Atlantic Slave Trade", Philip Curtin, History Net, accessed 9 July 2008

- 1 2 Les Guides Bleus: Afrique de l'Ouest (1958 ed.), p. 123

- ↑ "21 World Heritage Sites you have probably never heard of". Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ .Araujo, Ana Lucia. Public Memory of Slavery: Victims and Perpetrators in the South Atlantic (Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2010); Araujo, Ana Lucia. Shadows of the Slave Past: Memory, Heritage, and Slavery (New York: Routledge, 2014), 57-65.

- ↑ Max Fisher (June 28, 2013). "What Obama really saw at the 'Door of No Return,' a disputed memorial to the slave trade". The Washington Post.

- ↑ For last period, see for example, Guthrie, William (1798). A New Geographical, Historical and Commercial Grammar and Present State of the Several Kingdoms of the World, 2. London: Charles Dilly ... and G.G. and J. Robinson. pp. 819–820.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Thiaw, Ibrahima. Slaves without Shackles: An Archaeology of Everyday Life on Gorée Island, Senegal. pp. 147–165. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197264782.003.0008.

- 1 2 3 4 Thiaw, I. 2003. The Gorée Archaeological Project (GAP): Preliminary results. Nyame Akuma 60: 27-35

- ↑ Cheikh Anta Diop (1994). The Island and the Historical Museum. Publication of the Historical Museum. pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Cheikh Anta Diop (1994). The Island and the Historical Museum. Publication of the Historical Museum. p. 68.

- ↑ "Goree Archaeology", Rice University, accessed 8 July 2009

- 1 2 3 Thiaw, Ibrahima (2011-01-01). Okamura, Katsuyuki; Matsuda, Akira, eds. New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology. Springer New York. pp. 127–138. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0341-8_10. ISBN 9781461403401.

- ↑ "New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology - Springer". doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0341-8.

- ↑ Curtin, Philip D. (1969). The Atlantic slave trade : a census / by Philip D. Curtin. Madison, Wisconsin: Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Further reading

- Camara, Abdoulaye & Joseph Roger de Benoïst. Histoire de Gorée, Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose, 2003

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gorée. |

- UNESCO

- Photos of Goree on Flickr

- Mairie de Gorée (French)

- Archaeological Research on Gorée, Rice University

- Gorée and the Slave Trade, Philip Curtin, African Threads, History Net

- George W. Bush's visit