Golden-shouldered parrot

| Golden-shouldered parrot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male and female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Superfamily: | Psittacoidea |

| Family: | Psittaculidae |

| Subfamily: | Platycercinae |

| Tribe: | Platycercini |

| Genus: | Psephotus |

| Species: | P. chrysopterygius |

| Binomial name | |

| Psephotus chrysopterygius Gould, 1858 | |

The golden-shouldered parrot (Psephotus chrysopterygius) is a rare bird of southern Cape York Peninsula, in Queensland, Australia. A small parrot related to the more common red-rumped parrot, it is considered to be a superspecies with the hooded parrot (P. dissimilis) of the Northern Territory and the apparently extinct paradise parrot of Queensland and New South Wales.

Description

-6.jpg)

The golden-shouldered parrot is 23–28 cm long and weighs 54–56 g. The adult male is mainly blue and has a characteristic yellow over the shoulder area. It has a black cap and pale yellow frontal band. It has an extended dark salmon pink lower belly, thighs and undertail-coverts. It has a grey-brown lower back.

Adult females are mainly dull greenish-yellow, and have a broad cream bar on the underside of the wings. The head in older females has a charcoal grey cap. The feathers of the vent area are a pale salmon pink. Juveniles are similar to the adult female though newly fledged males have a brighter blue cheek patch than females of the same age.[2]

Habitat

The golden-shouldered parrot lives in open forested grassland liberally populated by numerous termite species and their mounds. Often these mounds are found every few metres apart. The parrot feeds on the seeds of small grass species and several months of the year, principally those prior to the onset of the wet season, the birds are almost entirely dependent on the small but plentiful seed of firegrass (Schizachyrium fragile). An important habitat requirement is the presence of suitably sized terrestrial termite mounds, in which the birds nest. This has led to the Golden shouldered parrot and its relatives being known as the antbed parrots.

Breeding

The golden-shouldered parrot will build a nest in the taller magnetic termite mounds (up to 2 m high)but surveys point to the preference for the lower dome type mounds. This may be to do with the slower heating up and cooling of the smaller denser mounds.Commonly they dig a burrow into the mound when wet season rains have softened the substrate of the mounds. Typically a 50 –350 mm long tunnel is dug down into the mound ending in the nesting chamber. The clutch size is between 3–6 eggs, which are incubated for 20 days. The termite occupants of the mound use a natural form of airconditioning to preserve the climatic conditions of their colony and this process regulates the temperature of the parrot's nest chamber at around 28-30 degrees C. Temperature surveys have shown however, a range of 13-35 degrees C. These conditions have led to the parrots developing a habit of leaving the eggs at night beginning around the 10th day after hatching. A symbiotic relationship is present between the Golden shouldered parrot and a moth species (Trisyntopa scatophaga) that is worthy of note. Found in around half of parrot nests, the moths seek out the newly dug nest tunnels and deposit their eggs in the entrance. The hatching moth larvae consume the faeces of the nestling parrots therefore helping to keep the nest chamber clean. Whether the parrots receive any other benefits from the presence of moths is arguable as not all nests contain moth larvae.

There appears to be a tendency for more male parrots relative to females to be born. This may be to counter the increased predation that males appear to suffer in the wild.

Status

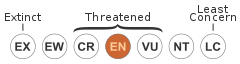

The golden-shouldered parrot is listed as endangered (CITES I), with population surveys pointing to a total wild population of around 2,000 birds with around 300 breeding pairs. The remaining majority of birds are thought to be juvenile birds in their first year of life.

The species has a restricted range and suffers from a variety of threats, including predation by feral cats, tourist disturbance as well as feral pigs which disturb and dig out nests. The main threat however has been the changes to traditional Aboriginal burning regimes in the grasslands upon whose seeds the birds depend. These so-called "cool fires" created a mosaic of burnt landscape allowing wildlife to move to remaining food resources and reveals fallen seed that is hidden by dried grass cover. Hot uncontrolled wildfires destroy all seed stores in the environment and favour the intrusion of teatree species into grassland habitats. The cover that is created by these thickets of teatree also allow the parrot's main predator, the pied butcherbird (Cracticus nigrogularis), a more successful kill rate on the parrots, primarily upon the juvenile population and adult males. A number of cases have been noted where a juvenile male has taken over the role of an adult male ( that has been predated) and is feeding the chicks of that deceased male. This may be an adaptation to the increased rate of predation on adult males in comparison to females. In captivity it is noted that golden-shouldered parrots will readily accept an new partner and this may be related to this wild breeding behaviour. Sites identified by BirdLife International as being important for golden-shouldered parrot conservation are Morehead River and Staaten River.[3] The ongoing conservation work of the owners of Artemis Station should also be noted. These graziers have been monitoring and providing conservation works on their property for the benefit of the Golden shouldered parrot since the 1970s. The reinstating of former burning practices and the temporary removal of cattle from prime breeding sites has aided the parrot's survival. The recent provision of feeding stations in order to help juvenile birds through the perilous first months of the wet season has also been undertaken. This period when heavy flooding rains results in any remaining seed being washed away or drowned and many young birds perish before newly sprouted grass can provide new seed. The conservation effort toward this species seems to be resulting in a stabilization of the population decline but no notable increase in numbers has been reported.

The Golden shouldered parrot is scarce in captivity. A population of perhaps 1,000 birds in Australia and perhaps 300 held in overseas aviaries means a limited gene pool is available. A dedicated group of breeders in Australia have attempted to promote the species and ensure that a viable breeding population is maintained in captivity. Many international breeders are also working toward this same goal.

The provision of heated nest boxes for breeding birds and the replication of a wild type diet is being used to try and formulate a successful regime leading to more predictable breeding results. Aviary birds can tend to become too fat if fed too rich a diet, resulting in infertility issues. The tendency to aggression between pairs means the keeping of one pair to an aviary and solid partitions between aviaries is essential to prevent injuries.The provision of earth floors in aviaries is considered best practice. Suspended flights do not allow for the parrots need to dig and feed on the ground as they do in the wild.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Psephotus chrysopterygius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ "Species factsheet: Psephotus chrysopterygius". BirdLife International (2008). Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ↑ "Golden-shouldered Parrot". Important Bird Areas. BirdLife International. 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-01.

- Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol 4. Edited by del Hoyo, Elliott and Sargatal. ISBN 84-87334-22-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psephotus chrysopterygius. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Psephotus chrysopterygius |