Gomoku

Gomoku is an abstract strategy board game. Also called Gobang or Five in a Row, it is traditionally played with Go pieces (black and white stones) on a go board with 19x19 (15x15) intersections;[1] however, because pieces are not moved or removed from the board, gomoku may also be played as a paper and pencil game. This game is known in several countries under different names.

Black plays first if white did not win in the previous game, and players alternate in placing a stone of their color on an empty intersection. The winner is the first player to get an unbroken row of five stones horizontally, vertically, or diagonally.

Origin

It originated in Japan during the Heian period. The name "Gomoku" is from the Japanese language, in which it is referred to as gomokunarabe (五目並べ). Go means five, moku is a counter word for pieces and narabe means line-up. The game is also popular in Korea, where it is called omok (오목 [五目]) which has the same structure and origin as the Japanese name.

The Japanese call this game Go-moku (five stones). In the nineteenth century, the game was introduced to Britain where it was known as Go Bang, said to be a corruption of the Japanese word goban, said to be adopted from Chinese k'i pan (qí pán) "chess-board."[2]

Official rules

Besides many variations around the world, the "Swap2" rule (based on "swap" from Renju) is currently adapted in tournaments among professional players. The first player places 3 stones (2 black 1 white, if black goes first) on the board, the second player has the choice to take black/white or to place 2 more stones to change the shape and let the first player choose color.[3] This is essentially a slightly more elaborate pie rule.

Swap2 solved the low complexity problem[4] and makes the game fairer. Like other rules and variations, 100% fairness can be reached by playing two alternating games for each point.

Variations

Black (the player who makes the first move) was long known to have a big advantage, even before L. Victor Allis proved that black could force a win (see below). So a number of variations are played with extra rules that aimed to reduce black's advantage.

- Standard gomoku requires a row of "exactly" five stones for a win: rows of six or more, called overlines, do not count.

- Free-style gomoku requires a row of five or more stones for a win.

Caro

- In Caro (also called Gomoku+, popular among Vietnamese), the winner must have an unbroken row of five stones and this row must not be blocked at both ends. This rule makes Gomoku more flexible and provides more power for White to defend.

Omok

- Omok is played the same as Standard Gomoku; however, it is played on a 19×19 board and does not include the rule of three and three. The overlines rules still apply.

Optional ("house") rules

- The rule of three and three bans a move that simultaneously forms two open rows of three stones (rows not blocked by an opponent's stone at either end).

- The rule of four and four bans a move that simultaneously forms two rows of four stones (open or not).

- Alternatively, a handicap may be given such that after the first "three and three" play has been made, the opposing player may place two stones as their next turn. These stones must block an opponent's row of three.

- Efforts to improve fairness by reducing first-move advantage include the rule of swap, generalizable as "swap-(x,y,z)" and characterizable as a partially compounded and partially iterated version of the pie rule ("one person slices; the other chooses"): One player places on the board x stones of the first-moving color and a lesser number y stones of the second-moving color ("slicing" in the pie metaphor); the other player is entitled to choose between a) playing from the starting position, in which case the selecting player is also entitled to choose which color to play, and b) placing z (usually [(x - y) + 1]) more stones on the board at locations of that player's choice ("reslicing" in the pie metaphor, with limitations created by the board's existing setup akin to limitations arising from the existing slices in the pie), in which case the former player is entitled to choose which color side to play.

Specific variations

- Renju is played on a 15×15 board, with the rules of three and three, four and four, and overlines applied to Black only and with opening rules, some of which are following the swap pattern.

- Ninuki-renju or Wu is a variant which adds capturing to the game; it was published in the USA in a slightly simplified form under the name Pente.

Theoretical generalizations

- m,n,k-games are a generalization of gomoku to a board with m×n intersections, and k in a row needed to win.

- Connect(m,n,k,p,q) games are another generalization of gomoku to a board with m×n intersections, k in a row needed to win, p stones for each player to place, and q stones for the first player to place for the first move only. Each player may play only at the lowest unoccupied place in a column. Connect(m,n,6,2,1) is the most interesting one and is called Connect6.

Analysis

Computer search by L. Victor Allis has shown that on a 15×15 board, black wins with perfect play.[4] This applies regardless of whether overlines are considered as wins, but it assumes that the rule of three and three is not used. It seems very likely that black wins on larger boards too. In any size of a board, freestyle gomoku is an m,n,k-game, and it is known that the second player does not win. With perfect play, either the first player wins or the result is a draw.

Reich proved that Generalized gomoku is PSPACE-complete.[5] He also observed that the reduction can be adapted to the rules of k-in-a-Row for fixed k. Although he did not specify exactly which values of k are allowed, the reduction would appear to generalize to any k ≥ 5.[6]

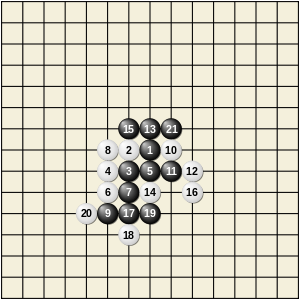

Example game

This game on the 15×15 board is adapted from the paper "Go-Moku and Threat-Space Search".[7]

The opening moves show clearly black's advantage. An open row of three (one that is not blocked by an opponent's stone at either end) has to be blocked immediately, or countered with a threat elsewhere on the board. If not blocked or countered, the open row of three will be extended to an open row of four, which threatens to win in two ways.

White has to block open rows of three at moves 10, 14, 16 and 20, but black only has to do so at move 9. Move 20 is a blunder for white (it should have been played next to black 19). Black can now force a win against any defence by white, starting with move 21.

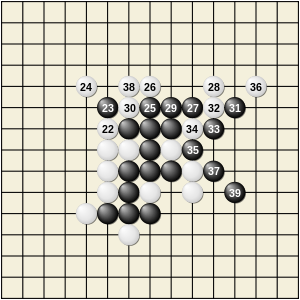

There are two forcing sequences for black, depending on whether white 22 is played next to black 15 or black 21. The diagram on the right shows the first sequence. All the moves for white are forced. Such long forcing sequences are typical in gomoku, and expert players can read out forcing sequences of 20 to 40 moves rapidly and accurately.

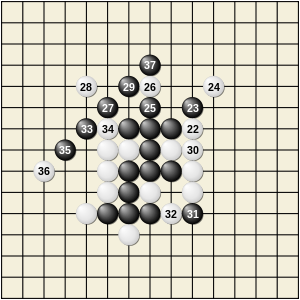

The diagram on the right shows the second forcing sequence. This diagram shows why white 20 was a blunder; if it had been next to black 19 (at the position of move 32 in this diagram) then black 31 would not be a threat and so the forcing sequence would fail.

World championships

World Championships in Gomoku have occurred 2 times in 1989, 1991.[8] Since 2009 the tournament resumed, the opening rule being played was changed and now is swap2.

List of the tournaments occurred and title holders follows.

| Title year | Hosting city, country | Champion | Opening rule |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | Kyoto |

Gomoku pro (3rd outside 5X5) | |

| 1991 | Moscow |

Gomoku pro (3rd outside 5X5) | |

| 2009 | Pardubice |

Gomoku swap2 | |

| 2011 | Huskvarna |

Gomoku swap2 | |

| 2013 | Tallinn |

Gomoku swap2 | |

| 2015 | Suzdal |

Gomoku swap2 |

| Title year | Hosting city, country | Champion | Opening rule |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Tallinn |

Gomoku swap2 |

Computers and Gomoku

People have been applying the artificial intelligence technique on playing gomoku for several decades. In 1994, L. V. Allis raised the algorithm of proof-number search (pn-search) and dependency-based search (db-search), and proved that when starting from an empty board, the first player has a winning strategy using these searching algorithms.[4] In 2001, the winning strategy was also approved for renju, a variation of gomoku, when there was no limitation on the opening stage.[9]

However, neither the theoretical values of all legal positions, nor the balanced rules used by the professional gomoku players have been solved yet,[4] so the topic of gomoku artificial intelligence is still a great challenge for computer scientists, such as the problem on how to improve the gomoku AIs to make it more strategic and competitive. Nowadays, most of the state-of-the-art gomoku AIs are based on the alpha-beta pruning framework.

There exist several well-known tournaments for gomoku AIs since 1989. The Computer Olympiad started with the gomoku game in 1989, but gomoku has not been in the list since 1993.[10] The Renju World Computer Championship was started in 1991, and held for 4 times until 2004.[11][12] The Gomocup tournament is played since 2000 and taking place every year, still active now, with more than 30 participants from about 10 countries.[13] The Hungarian Computer Go-Moku Tournament was also played twice in 2005.[14][15] There were also two AI vs. Human tournament played in the Czech Republic in 2006 and 2011.[16][17]

See also

- Game theory

- Connection game

- advanced tic tac toe

- Board game

- Renju

- Irensei

- Solved board games

- Connect6, a revised version of Gomoku

- Pegity

- Pente

- Connect Four

- Reversi

References

In the online MMORPG Maplestory, a minigame named "OMOK" is available and fully playable with many of the same rules, including the "No-double-unblocked-threes" rule.

- ↑ "Gomoku - Japanese Board Game". Japan 101. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- ↑ OED citations: 1886 GUILLEMARD Cruise ‘Marchesa’ I. 267 Some of the games are purely Japanese..as go-ban. Note, This game is the one lately introduced into England under the misspelt name of Go Bang. 1888 Pall Mall Gazette 1. Nov. 3/1 These young persons...played go-bang and cat's cradle. The board below shows the three types of winning arrangements as they might appear on an 8x8 Petteia board. Obviously the cramped conditions would result in a draw most of the time, depending on the rules. Play would be easier on a larger Latrunculi board of 12x8 or even 10x11. .

- ↑ "Gomoku - swap2 rule". renju.net. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- 1 2 3 4 L. Victor Allis (1994). Searching for Solutions in Games and Artificial Intelligence (PDF). Ph.D. thesis, University of Limburg, The Netherlands. ISBN 90-900748-8-0.

- ↑ Stefan Reisch (1980). "Gobang ist PSPACE-vollständig (Gomoku is PSPACE-complete)". Acta Informatica. 13: 59–66. doi:10.1007/bf00288536.

- ↑ Demaine, Erik; Hearn, Robert. "Playing Games with Algorithms: Algorithmic Combinatorial Game Theory".

- ↑ Allis, L. V., Herik, H. J., & Huntjens, M. P. H. (1993). Go-moku and threat-space search. University of Limburg, Department of Computer Science.

- ↑ "The Renju International Federation portal - RenjuNet". Renju.net. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ Wágner, J., & Virág, I. (2001). Solving Renju. ICGA journal, 24(1), 30-35.

- ↑ "Go-Moku (ICGA Tournaments)". www.game-ai-forum.org. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ↑ "Renju Computer World Championship". www.5stone.net. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ↑ "4-th World Championship among Computer programs". Nosovsky Japanese Games Home Page. Retrieved 2016-06-03.

- ↑ "Gomocup - The Gomoku AI Tournament". Gomocup. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ↑ "Hungarian Computer Gomoku Tournament 2005 | GomokuWorld.com". gomokuworld.com. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ↑ "2nd Hungarian Computer Go-Moku Open Tournament". sze.hu. Retrieved 2016-06-03.

- ↑ "The 1st tournament AI vs. Human (November the 11th, 2006) | Gomocup". gomocup.org. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ↑ "AI vs. Člověk 2011 | Česká federace piškvorek a renju". www.piskvorky.cz. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- Further reading

- Five-in-a-Row (Renju) For Beginners to Advanced Players ISBN 4-87187-301-3