Glacier morphology

Glacier morphology, or the form a glacier takes, is influenced by temperature, precipitation, topography, and other factors. Types of glaciers range from massive ice sheets, such as the Greenland ice sheet or those in Antarctica, to small cirque glaciers perched on a mountain. Glaciers types can be grouped into two main categories, based on whether ice flow is constrained by the underlying bedrock topography.

Unconstrained

Ice sheets and ice caps

Ice sheets and ice caps cover vast areas and are unconstrained by the underlying topography having a radial flow. The main distinction between the two is the size of their surface, with ice caps covering areas less than 50,000 square kilometers, while ice sheets span larger areas.[1] Ice sheets and ice caps can be classified further.

Ice domes

An ice dome is an upstanding ice surface located in the accumulation zone of the higher altitude portions of an ice cap or ice sheet. Ice domes are nearly symmetrical with a convex or parabolic surface shape. They tend to develop evenly over a land mass that may be either a topographic height or a depression —often reflecting the subglacial topography. In ice sheets, domes may reach a thickness that may exceed 3,000 m, but in ice caps the thickness of the dome is roughly up to several hundred metres. In glaciated islands ice domes are usually the highest point of the ice cap.[2]

An example of an ice dome is Kupol Vostok Pervyy in Alger Island, Franz Josef Land, Russia.[3]

Ice streams

Ice streams rapidly channel ice flow out to the sea or ocean, where it may feed into an ice shelf. At the margin between ice and water, ice calving takes place, with icebergs breaking off. Ice streams are bounded on the sides by areas of slowly moving ice.[4]

Constrained

Icefield

An icefield covers a relatively large area, usually located in mountainous terrain. The underlying topography controls or influences the form that an icefield takes. Often, nunataks poke through the surface of icefields. Examples of icefields include the Columbia Icefield in the Canadian Rockies and the Northern and Southern Patagonian Ice Field in Chile and Argentina.

Outlet glaciers

Outlet glaciers are channels of ice that flow out of ice sheets, ice caps or icefields, but are constrained on the sides with exposed bedrock.

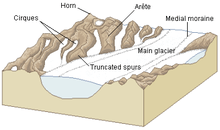

Valley glaciers

Valley glaciers can be outlet glaciers that provide drainage for icefields, icecaps or icesheets and they are also constrained by underlying topography. But they may also form up in mountain ranges as gathering snow turns to ice. Ice-free exposed bedrock and slopes often surround valley glaciers, providing snow and ice from above to accumulate on the glacier via avalanches. True fjords are formed when valley glaciers retreat and sea water fills the void.

Piedmont glaciers

Piedmont glaciers are valley glaciers which have spilled out onto relatively flat plains, where they spread out into bulb-like lobes.[6] The Malaspina Glacier in Alaska is the largest example of this.

Cirque glaciers

Snow may be situated on the leeward slope of a mountain, where it is sheltered and accumulates in small depressions. In these depressions, snow persists through summer months, and is transformed into glacier ice. The glaciers which are built up now, the cirque glaciers form cirques, bowl-shaped valleys on the side of the mountains.

References

- ↑ "Introduction to Glaciers". National Park Service.

- ↑ Atle Nesje, Svein Olat Dahl, Glaciers and Environmental Change. Rotledge, p. 50

- ↑ Kupol Vostok Pervyy: Russia

- ↑ McIntyre, N.F. (1985). "The Dynamics of Ice Sheet Outlets". Journal of Glaciology. 31: 99–107. Bibcode:1985JGlac..31...99M.

- ↑ Elephant Foot Glacier at NASA Earth Obsevatory

- ↑ What types of glaciers are there? National Snow and Ice Data Center.

External links

![]() Media related to Glacial geomorphology at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Glacial geomorphology at Wikimedia Commons