The Giving Tree

|

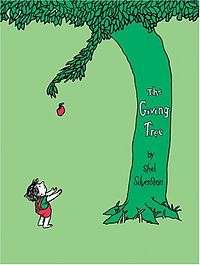

Cover depicting the tree giving away an apple | |

| Author | Shel Silverstein |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Shel Silverstein |

| Cover artist | Shel Silverstein |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's picture book |

| Publisher | Harper & Row |

Publication date | October 7, 1964 |

| ISBN | 978-0-06-025665-4 |

The Giving Tree is a children's picture book written and illustrated by Shel Silverstein. First published in 1964 by Harper & Row, it has become one of Silverstein's best known titles and has been translated into numerous languages.

Despite the recognition that the book has received, it has been described as "one of the most divisive books in children’s literature."[1] The controversy concerns whether the relationship between the main characters (a boy and a tree) should be interpreted as positive (e.g., the tree gives the boy selfless love) or as negative (e.g., the boy and the tree have an abusive relationship).[2][3][4] Scholastic designates the interest level of this book to range from kindergarten to second grade.[5]

Background

Silverstein had difficulty finding a publisher for The Giving Tree.[6][7] An editor at Simon & Schuster rejected the book's manuscript because he felt that it was "too sad" for children and "too simple" for adults.[6][7] Tomi Ungerer encouraged Silverstein to approach Ursula Nordstrom, who was a publisher with Harper & Row.[6]

An editor with Harper & Row stated that Silverstein had made the original illustrations "scratchy" like his cartoons for Playboy, but that he later reworked the art in a "more pared-down and much sweeter style."[3] The final black-and-white drawings have been described as "unadorned… visual minimalism."[2] Harper & Row published a small first edition of the book, consisting of only 5,000-7,500 copies, in 1964.[8]

Plot summary

The book follows the lives of a female apple tree and a boy, who develop a relationship with one another. The tree is very "giving" and the boy evolves into a "taking" teen-ager, man, then elderly man. Despite the fact that the boy ages in the story, the tree addresses the boy as "Boy" his entire life.

In his childhood, the boy enjoys playing with the tree, climbing her trunk, swinging from her branches, and eating her apples. However, as the boy grows older, he spends less time with the tree and tends to visit her only when he wants material items at various stages of his life. In an effort to make the boy happy at each of these stages, the tree gives him parts of herself, which he can transform into material items, such as money (from her apples), a house (from her branches), and a boat (from her trunk). With every stage of giving, "the Tree was happy".

In the final pages, both the tree and the boy feel the sting of their respective "giving" and "taking" nature. When only a stump remains for the tree, she is not happy, at least at that moment. The boy does return as a tired elderly man to meet the tree once more and states that all he wants is "a quiet place to sit and rest," which the tree could provide. With this final stage of giving, "the Tree was happy".

Reception

Interest in the book increased by word of mouth; for example, in churches "it was hailed as a parable on the joys of giving."[6] As of 2001, over 5 million copies of the book had been sold, placing it 14th on a list of hardcover "All-Time Bestselling Children's Books" from Publishers Weekly.[9] By 2011, there were 8.5 million copies in print.[7]

In a 1999-2000 National Education Association online survey of children, among the "Kids' Top 100 Books," the book was 24th.[10] Based on a 2007 online "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children" poll by the National Education Association, the book came in third.[11] It was 85th of the "Top 100 Picture Books" of all time in a 2012 poll by School Library Journal.[12] Scholastic Parent & Child magazine placed it #9 on its list of "100 Greatest Books for Kids" in 2012.[13] As of 2013, it ranked third on a Goodreads list of "Best Children's Books."[14]

Interpretations

The book has generated various opinions on how to interpret the relationship between the tree and the boy. Some possible interpretations include:[15][16]

Philosophical interpretation

Some people believe that the tree represents a "giver", who is happy because of her capacity to "give" and the boy (post-childhood) represents a "taker", who continually "takes" in his quest for happiness, which he never achieves.

Religious interpretations

Ursula Nordstrom attributed the book's success partially to "Protestant ministers and Sunday-school teachers", who believed that the tree represents "the Christian ideal of unconditional love."[17]

Environmental interpretation

Some people believe that the tree represents Mother Nature and the boy represents humanity. That is, the book is an "allegory about the responsibilities a human being has for living organisms in the environment,"[18] that is, as a "what-not-to-do role model."[16] The book has been used to teach children environmental ethics.[19] By the last drawing (in which the old man sits on the stump) it is clear that the boy has used the tree up completely and there is only one use left, which is to be a seat for the old man. The man seems to have little appreciation or remorse for how he has abused the tree.[20] The condition of the tree depicts how humans are constantly taking from the environment until there is nothing left to enjoy, neither beauty nor bounty.

Friendship interpretation

Some people believe that the relationship between the boy and the tree is one of friendship. As such, the book teaches children "as your life becomes polluted with the trappings of the modern world — as you 'grow up' — your relationships tend to suffer if you let them fall to the wayside."[20] One criticism of this interpretation is that the tree appears to be an adult when the boy is young, and cross-generational friendships are rare.[20]

Parent-child interpretation

The most-discussed interpretation of the book is that the tree and the boy have a parent-child relationship, as in a 1995 collection of essays about the book edited by Richard John Neuhaus in the journal First Things.[21] Among the essayists, some were positive about the relationship; for example, Amy A. Kass wrote about the story that "it is wise and it is true about giving and about motherhood," and her husband Leon R. Kass encourages people to read the book because the tree "is an emblem of the sacred memory of our own mother's love."[21] However, other essayists put forth negative views. Mary Ann Glendon wrote that the book is "a nursery tale for the 'me' generation, a primer of narcissism, a catechism of exploitation," while Jean Bethke Elshtain felt that the story ends with the tree and the boy "both wrecks."[21]

A 1998 study using phenomenographic methods found that Swedish children and mothers tended to interpret the book as dealing with friendship, while Japanese mothers tended to interpret the book as dealing with parent-child relationships.[15]

Interpretation as satire

Some authors believe that the book is not actually intended for children, but instead should be treated as a satire aimed at adults along the lines of A Modest Proposal by Jonathan Swift.[22][23]

Critics

Many writers harshly criticize the book for the way in which it depicts the relationship:[24]

Totally self-effacing, the 'mother' treats her 'son' as if he were a perpetual infant, while he behaves toward her as if he were frozen in time as an importunate baby. This overrated picture book thus presents as a paradigm for young children a callously exploitative human relationship — both across genders and across generations. It perpetuates the myth of the selfless, all-giving mother who exists only to be used and the image of a male child who can offer no reciprocity, express no gratitude, feel no empathy — an insatiable creature who encounters no limits for his demands.

Other writers would counter-argue that the assumption that the story represents a mother-child relationship may be incorrect and that the tree may continually refer to the boy as "Boy" because the boy never emotionally matures and perpetually acts like a child.

Critics of the book point out that the boy never thanks the tree for its gifts.[25] An editor with Harper & Row was quoted as saying that the book is "about a sadomasochistic relationship" and that it "elevates masochism to the level of a good."[3]

One college instructor discovered that the book caused both male and female remedial reading students to be angry because they felt that the boy exploited the tree.[26] For teaching purposes, he paired the book with a short story by Andre Dubus entitled "The Fat Girl" because its plot can be described as The Giving Tree "in reverse."[26]

Other writers are of the opinion that interpretations of the book are heavily influenced by an individual's life experiences. That is, a parent, who is overwhelmed with parenting a child, may identify with the tree. A person who was in an exploitative relationship with a narcissist, may also identify with the tree. The psychology behind the reactions to this book would be an interesting area for further study.

Author's photograph

The photograph of Silverstein on the back cover of the book has attracted attention.[1][27] One writer described the photograph as showing the author's "jagged menacing teeth" and "evil, glaring eyes."[28] Another writer compared the photograph to the one on the back of Where the Sidewalk Ends in which Silverstein resembles "the Satanist Anton LaVey."[29] In the book Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Last Straw, the father threatens the protagonist with the photograph to make sure that he does not leave his room at night.[1][30]

Other versions

- A short animated film of the book, produced in 1973, featured Silverstein's narration.[31][32]

- Silverstein also wrote a song of the same name, which was performed by Bobby Bare and his family on his album Singin' in the Kitchen (1974).[33]

- Silverstein created an adult version of the story in a cartoon entitled "I Accept the Challenge."[29] In the cartoon, a nude woman cuts off a nude man's arms and legs with scissors, then sits on his torso in a pose similar to the final drawing in Giving Tree in which the old man sits on the stump.[29]

Cultural influences and adaptations

Jackson and Dell (1979) wrote an "alternative version" of the story for teaching purposes that was entitled "The Other Giving Tree."[22] It featured two trees next to each other and a boy growing up. One tree acted like the one in The Giving Tree, ending up as a stump, while the other tree stopped at giving the boy apples, and does not give the boy its branches or trunk. At end of the story, the stump was sad that the old man chose to sit under the shade of the other tree.[22]

The Giving Tree Band took its name from the book.[34] Plain White T's EP Should've Gone to Bed has a song The Giving Tree, written by Tim Lopez.

The 2010 short film I'm Here, written and directed by Spike Jonze, is based on The Giving Tree; the main character Sheldon is named after Shel Silverstein.[35]

In the film 'Guardians of the Galaxy' the hero of the film 'Starlord' refers to the mercenary named 'Groot' as (The) Giving tree. Groot is a humanoid 'tree like' alien.

References

- 1 2 3 Bird, Elizabeth (May 18, 2012). "Top 100 Picture Books #85: The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein". School Library Journal "A Fuse #8 Production" blog. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- 1 2 Spitz, Ellen Handler (1999). Inside Picture Books. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 142–144. ISBN 0300076029.

- 1 2 3 Marcus, Leonard S. (March–April 1999). "An Interview with Phyllis J. Fogelman" (PDF). Horn Book Magazine. 75 (2): 148–164. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Daly, Mary (1990). Gyn/Ecology: the Metaethics of Radical Feminism. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 90. ISBN 0807014133.

- ↑ "The Giving Tree By Shel Silverstein". Scholastic.

- 1 2 3 4 Cole, William (September 9, 1973). "About Alice, a Rabbit, a Tree...". The New York Times. p. 394.

- 1 2 3 Paul, Pamela (September 16, 2011). "The Children's Authors Who Broke the Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Natov, Roni & Geraldine DeLuca (1979). "Discovering Contemporary Classics: an Interview with Ursula Nordstrom". The Lion and the Unicorn. 3 (1): 119–135. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0355. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Roback, Diane, Jason Britton, and Debbie Hochman Turvey (December 17, 2001). "All-Time Bestselling Children's Books". Publishers Weekly. 248 (51). Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ National Education Association. "Kids' Top 100 Books". Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ National Education Association (2007). "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children". Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Bird, Elizabeth (May 18, 2013). "Top 100 Picture Books Poll Results". School Library Journal "A Fuse #8 Production" blog. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Parent & Child 100 Greatest Books for Kids" (PDF). Scholastic Corporation. 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Best Children's Books". Goodreads. 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- 1 2 Pramling Samuelsson, Ingrid; Mauritzson, Ulla; Asplund Carlsson, Maj; Ueda, Miyoko (1998). "A Mother and a Friend: Differences in Japanese and Swedish Mothers' Understanding of a Tale". Childhood. 5 (4): 493–506. doi:10.1177/0907568298005004008. ISSN 0907-5682.

- 1 2 Fraustino, Lisa Rowe (2008). "At the Core of The Giving Tree's Signifying Apples". In Magid, Annette M. You Are What You Eat: Literary Probes into the Palate. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars. pp. 284–306. ISBN 9781847184924.

- ↑ Marcus, Leonard S. (May 15, 2005). "'Runny Babbit': Hoppity Hip". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Fredericks, Anthony D. (1997). "26. The Giving Tree". The Librarian's Complete Guide to Involving Parents Through Children's Literature Grades K-6. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited. p. 28. ISBN 1563085380.

- ↑ Goodnough, Abby (April 16, 2010). "The Examined Life, Age 8". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Belkin, Lisa (September 8, 2010). "Children's Books You (Might) Hate". "Motherlode: Adventures in Parenting" blog. New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- 1 2 3 May, William F., Amy A. Kass, Marc Gellman, Midge Decter, Gilbert Meilaender, Mary Ann Glendon, William Werpehowski, Timothy Fuller, Leon R. Kass, Timothy P. Jackson, Jean Bethke Elshtain, Richard John Neuhaus (January 1995). "The Giving Tree: A Symposium". First Things. The Institute on Religion and Public Life. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Jackson, Jacqueline & Carol Dell (1979). "The Other Giving Tree". Language Arts. 56 (4): 427–429. JSTOR 41404822.

- ↑ Strandburg, Walter L. & Norma J. Livo (1986). "The Giving Tree or There is a Sucker Born Every Minute". Children's Literature in Education. 17 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1007/BF01126946.

- ↑ Spitz, Ellen Handler (May–June 1999). "Classic children's book". American Heritage. 50 (3): 46. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Prosapio, Winter (May 12, 2006). "A Lesson from 'The Giving Tree'". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- 1 2 Juchartz, Larry R (December 2003 – January 2004). "Team Teaching with Dr. Seuss and Shel Silverstein in the College Basic Reading Classroom". Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 47 (4): 336–341.

- ↑ Kogan, Rick (July 12, 2009). "'SHELebration: A Tribute to Shel Silverstein' to Honor Writer Born in Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Ruhalter, Eric (January 11, 2010). "Children's books that creep me out: What was up with 'Natural Bear?'". New Jersey On-Line. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Thomas Jr.; Joseph T. (May–June 2005). "Reappraising Uncle Shelby" (PDF). Horn Book Magazine. 81 (3): 283–293. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Kinney, Jeff (2009). Diary of a Wimpy Kid: the Last Straw. New York: Amulet Books. pp. 17–19. ISBN 9780810970687.

- ↑ Bosustow, Nick, and Shel Silverstein (Producers); Hayward, Charlie O. (Director and Animator); Silverstein, Shel (Original Story, Music, and Narration) (1973). The Giving Tree (VHS). Chicago, IL: SVE & Churchill Media. OCLC 48713769.

- ↑ "The Giving Tree: Based on the Book and Drawings by Shel Silverstein". YouTube. Churchill Films. 1973. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Bobby Bare and the Family (Musicians); Silverstein, Shel (Principal Composer) (1973). Singin' in the Kitchen (LP). New York: RCA Victor. OCLC 6346534.

- ↑ Markstrom, Serena (June 18, 2010). "Giving Tree Band Takes Story to Heart". The Register-Guard. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Coates, Kristen (February 8, 2010). "[Sundance Review] Spike Jonze Creates Unique Love Story With 'I'm Here'". The Film Stage. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

'I was trying to take the influence of The Giving Tree, but write about relationships,' says Jonze. 'I love Shel Silverstein. I just love him.'

Further reading

- Moriya, Keiko (1989). "A Developmental and Crosscultural Study on the Interpersonal Cognition of Swedish and Japanese Children". Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. 33 (3): 215–227. doi:10.1080/0031383890330304.

- Asplund Carlsson, Maj; Pramling, Ingrid; Wen, Qiufeng; Izumi, Chise (1996). "Understanding a Tale in Sweden, Japan and China". Early Child Development and Care. 120 (1): 17–28. doi:10.1080/0300443961200102.

- Miller, Ellen (2012). "15: The Giving Tree and Environmental Philosophy: Listening to Deep Ecology, Feminism and Trees". In Costello, Peter R. Philosophy in Children's Literature. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. pp. 251–266. ISBN 9780739168233.

- Radeva, Milena (2012). "16: The Giving Tree, Women, and the Great Society". In Costello, Peter R. Philosophy in Children's Literature. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. pp. 267–283. ISBN 9780739168233.

- Hinson-Hasty, Elizabeth (2012). "Revisiting Feminist Discussions of Sin and Genuine Humility". Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. 28 (1): 108–114. doi:10.2979/jfemistudreli.28.1.108.

External links

- Lindsey, Charley (June 11, 2004). "Silverstein's 'The Giving Tree' Celebrates 40 Years in Print". Knight Ridder Newspapers.

- Westley, Christopher (October 21, 2004). "That Insufferable 'Giving Tree'". Mises Daily. Ludwig von Mises Institute.