Gitel Steed

| Gitel (Gertrude) Poznanski Steed | |

|---|---|

|

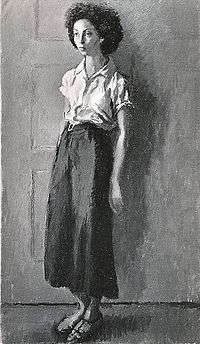

Raphael Soyer (1932) Girl in White Blouse, oil on canvas, a portrait of Gitel Steed at eighteen held in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum, New York. | |

| Born |

May 3, 1914 Cleveland, Ohio, USA |

| Died |

September 6, 1977 (aged 63) New York City |

| Education |

|

| Occupation | Anthropologist |

| Spouse(s) | Robert Steed (m.1947) |

| Children | Andrew Hart (b. 1953) |

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||

| Anthropology of kinship | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Basic concepts

|

||||||||||

|

Terminology |

||||||||||

|

Case studies |

||||||||||

|

Social anthropology Cultural anthropology | ||||||||||

| Anthropology |

|---|

|

Lists

|

|

Gitel (Gertrude) Poznanski Steed (May 3, 1914 – September 6, 1977) was an American cultural anthropologist known for her research in India 1950–52 (and returning in 1970) involving ethnological work in three villages to study the complex detail of their social structure. She supplemented her research with thousands of ethnological photographs of the individuals and groups studied, the quality of which was recognised by Edward Steichen. She experienced chronic illnesses after her return from the field, but nevertheless completed publications and many lectures but did not survive to finish a book The Human Career in Village India which was to integrate and unify her many-sided studies of human character formation in the cultural/historical context of India.[1][2]

Early life

Gertrude Poznanski was born on May 3, 1914, in Cleveland, Ohio, the home of her mother, Sarah Auerbach. She was the youngest of sisters Mary and Helen, who both later emigrated to Israel. Her father was Jakob Poznanski, a businessman and Polish native who had come to the United States from Belgium. When Poznanski was still a baby, the family moved to The Bronx, New York, where she was schooled at Wadleigh High. Though not religious, she adopted the Yiddish name of Gitel. Her mother was active in the women's suffrage movement and in leftist politics.

Dr. Steed began a BA in banking and finance at New York University, but embraced the Greenwich Village artistic and political life, often singing blues in nightclubs, and dropped out to take a job as a writer with the Works Progress Administration. Rafael Soyer painted portrait of her at eighteen, Girl in a White Blouse, (1932) which is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and she is the medusa-haired subject in Soyer's Two Girls 1933 (oil on canvas) at the Smart Museum. In 1933 she met the painter Robert Steed (b.1903), whom she married in 1947.

Introduction to anthropology

Philosopher Sidney Hook persuaded Steed to return to NYU and in 1938 she completed her B.A. with honors in sociology and anthropology, then studied as a graduate at Columbia University until 1940 as a Research Fellow in the Department of Anthropology under Professor Ruth Benedict whom she had met in 1937 and who in 1939 led Gitel Steed's first field experience among the Blackfoot Indians of Montana.[3] Benedict's Patterns of Culture[4] was published in 1934 and had become standard reading for anthropology courses in American universities for years, and Steed was influenced by Benedict's position in that book that, "A culture, like an individual, is a more or less consistent pattern of thought and action", and that each culture chooses from "the great arc of human potentialities" only a few characteristics which become the leading personality traits of the persons living in that culture. From 1939 to 1941, Steed undertook research for Vilhjalmur Stefansson, the explorer and writer on Inuit life then planning a two-volume Lives of the Hunters, on diet and subsistence; Steed worked on the South American Ona, Yahgan, and the Antillean Arawak and Carib, and from this formative experience began a dissertation on hunter-gatherer subsistence (not finished until 1969, well after she had established her career).[5]

In 1944, after the Nazi holocaust against the Jews was exposed, Gitel Steed set aside her anthropology and joined the Jewish Black Book Committee, an organization of the World Jewish Congress and other Jewish anti-Fascist groups. With a few peers, she participated during 1944 and 1945 in writing The Black Book: The Nazi Crime Against the Jewish People, an exhaustive indictment of calculated Nazi anti-Jewish war crimes intended for submission to the United Nations War Crimes Commission. Steed wrote "The Strategy of Decimation" published in 1946 for the Jewish Black Book Committee.

Steed taught at Hunter College in New York 1945 and 1947. While teaching at Fisk University in 1946/1947 she researched the Negro in the United States and in Africa and was managing editor of the University's and the American Council on Race Relations' monthly summary of "Race Relations" in America.[6][7]

In 1947–1949 she joined Dr. Ruth Bunzel in establishing the China group of Columbia's Research in Contemporary Cultures to study immigrant Chinese culture, primarily in New York City, from 1947 into 1949, working with migrants from the same community from China's Kwantung Provincal village, Toi Shan. She undertook life histories, community self-analysis, and projective tests, then proposed an extended field project in the Toi Shan community to understand the interdependency in social and economic relations between migrants and their kinsmen at home. Margaret Mead and others joined these Columbia comparative studies of contemporary cultures and they were incorporated into Mead's "The Study of Cultures at a Distance,"[8]

Steed planned "The Effects of Village Institutions on Personality in South China" and had funds granted for its continuation of her Chinese research in China.[1] However the occurrence of the Chinese Revolution of 1948 scuttled the project.

India

Steadfastly committed to field study of institutional determinants of individual and social character, she took up the suggestion of psychiatrist, Abram Kardiner, then associated with Columbia University's Department of Sociology, to pursue a similar study in India.[9][10] Shortly thereafter, Professor Theodore Abel, Department chairman, appointed Steed Director of a two-year field project of research in contemporary India.[11] Funding was received through a grant from the Department of the Navy.[12] She assembled a research team of Dr. James Silverberg, Dr. Morris Carstairs of Edinburgh University, and her husband Robert Steed, leaving for Indian 1949, where there was added a small staff of Indian workers. They included Bhagvati Masher and Kantilal Mehta, who worked as interpreters; Nandlal Dosajh, a psychologist;[13] N. Prabhudas, an economist who conducted the land utilization survey; and Jerome D'Souza as cook. In the second year of research, the team also included an Indian assistant, Tahera, as well as Americans Grace Langley and John Koos.[12] Her preparations were aided by her friendship with Gautam Sarabhai, a Gujarati Indian she had met in New York who assisted her in learning Hindustani. She also trained in the use of a professional camera.

The research goals and procedures were ambitious; to empirically bring together interactions of individual, culture, community and institutions, relating real individuals, not merely statistical patterns, for functional-historical analysis of character formation at the village level[14][15] in the three settlements chosen: Bakrana, a Hindu village in Gujarat; Sujarupa, a Hindu hamlet in Rajputana; and Adhon, a predominantly Muslim village in the United Provinces. Bakrana was a farming economy in fertile flatlands, exclusively Hindu and with an active caste system, largely untouched by the former British rule or by land reform changes current then in India. Sujarupa hamlet was a single-caste community in the upland valleys. Adhon was controlled by pro-independence Muslims, with more occupational castes and subgroups than Bakrana, with religious minorities.

Consolidation of ethnographic research in India

Steed returned to the United States in December 1951 with more than 30,000 pages of handwritten notes and some thousands of ethnological photographs, but infected with malaria, and shortly after her return she also developed diabetes which was particularly difficult to control and frequently put her in hospital. In addition, she suffered for over thirty years from pituitary cancer. Illness impaired her later career so that she was unable to receive her doctorate until 1969, 8 years before her death. In 1963, however, Conrad Arensberg wrote "her reputation and accomplishments are such as to make her lack of a PhD of little moment for her standing in the profession".[16] Her reputation also rests on her unpublished notes; the thousands of pages of interviews, observations, projective test results, life histories, and villagers' paintings, most of which are now in the special collections of the University of Chicago Libraries.

During the eleven years after returning from India and taking up a position at Hofstra College (now Hofstra University) in 1962 where she continued to her death in 1977, Steed had no university affiliation and promoted her work through seminars and lectures at Columbia University, University of Chicago, and the University of Pennsylvania. In 1953, Steed participated in a Social Science Research Council Conference on Economic Development in Brazil, India, and Japan, analyzing Dr. Morris Opler's "Cultural Aspects of Economic Development in Rural India", then later that year, 1953/4, she analyzed "The Individual, Family, and Community in Village India" in Columbia University's Department of Sociology graduate seminar on the psychodynamics of culture, chaired by Abram Kardiner. In 1954 Steed lectured on "The Child, Family and Community in Rural Gujarat" for the University of Chicago Seminar on Village India. The lectures and discussions are recorded in the archive. She presented in India symposia at meetings of the American Anthropological Association, and the Social Science Research Council.

Her one publication of note during this period was a chapter "Notes on an Approach to a Study of Personality Formation in a Hindu Village in Gujarat",[17] illustrating cultural and institutional influences on the personality of a single Rajput landowner,[18] for a volume Village India : studies in the little community[19] edited by Alan Beals and Dr. McKim Marriott, published in 1955;[20] Steed's chapter has been held up as a model for the treatment of personality problems and culture in India.[21] This, and the presentations she made at conferences assisted her in delimiting her doctoral thesis Caste and Kinship in Rural Gujarat: The Social Use of Space.

During these eleven years she gave birth to her son, Andrew Hart (b. 1953), and taught English at the Jefferson School, a Manhattan private school favored by the political left. Gitel and husband Robert Steed opened the doors of their house on West 23rd Street to visitors who included Ruth Bunzel, Sula Benet, Vera Rubin, Stanley Diamond, Alexander Lesser, Margaret Mead, and Conrad Arensberg.

In 1970 Steed revisited Bakrana, its population then doubled since her last visit, to observe the impact of the transforming politics in India.

Photographer

Edward Steichen, Director of the Department of Photography of the Museum of Modern Art, said Steed's photographs of Indian villagers, which though taken for the anthropological record and used as illustrations in varied lectures and presentations, ranked "with first-rate human interpretations by professional photographers."[22] In 1953, Steichen mounted Always the Young Strangers exhibition at MoMA in honour of Carl Sandberg's 75th birthday and included Gitel Steed's photos, six of which are in the Museum's permanent photographic collection. Steichen again used her pictures in the Museum's world-touring blockbuster, The Family of Man exhibition and book. Her photographs were republished in the New York Times, and featured in the St. Louis Post Despatch. While at Hofstra University, her photographic work was exhibited as part of the University's "Focus on India" presentation in 1962, and in 1963 Hofstra showed Steed photographs of Hindu and Muslim villagers. That same year Steed held the exhibition Child Life in Village India at the New Canaan Art Association Gallery in Connecticut and another, Cradle to Grave in Village India at the Hudson Guild Gallery in New York. In 1967 Vincent Fresno's Human Actions in Four Societies used a selection as illustrations.[1]

Death and legacy

Dr. Gitel Steed died in the night of September 6, 1977, evidently from a heart attack, at the age of sixty-three. She was survived by her husband and supporter for thirty years, artist Robert Steed, and by her son, Andrew.

The Gitel P. Steed papers 1907–1980 are archived in the University of Chicago Library and extend to approximately 13 linear metres (43 feet) of material. Most is data from her Columbia University Research in Contemporary India Field Project of 1949–1951 collected from three villages in western and northern India; extensive life histories of informants, psychological tests, typed notes, field notebooks, photographs, genealogies, histories, transcripts of interviews, and art work, mostly watercolours, by both researchers and child and adult villagers. These are joined by records of lectures and other publications relating to the India Project by Steed and by other scholars. Also held is data from Steed's previous fieldwork project among Chinese immigrants in New York City. The collection was given to the University of Chicago Committee on Southern Asian Studies by Robert Steed in 1978 and conveyed to the University of Chicago Library in 1984. Prior to their arrival, James Silverberg and McKim Marriott put the papers a preliminary order reflected in the collection's current organization. The collection was augmented by Robert Steed in 1985 and 1989, and by McKim Marriott and James Silverberg in 1994.

Publications

- 1946 The Strategy of Decimation. In The Black Book: The Nazi Crime against the Jewish People. The Jewish Black Book Committee and Ursula Wasserman, eds. pp. 111–240. New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce.

- 1947 Review of The Origin of Things, by Julius E. Lips. New York Times, June 15.

- 1947 Review of The City of Women, by Ruth Landes. New York Times, August 3, Pt. VII,

- 1947 Review of Men Out of Asia, by Harold S. Gladwin. New York Times, November 30, p. 14.

- 1948 Review of Zulu Woman, by Rebecca Hourwich Raynher. New York Times, June

- 1948 Review of Man and His Works, by Melville J. Herskovits. New York Times, November 14, Pt. VII, p. 26:4.

- 1948 Review of The Heathens, by William D. Howells. New York Times, November 14,

- 1953 Guest Exhibitor, Museum of Modern Art’s Edward Steichen Exhibition Always the Young Stangers. Photographs of Indian Hindu and Muslim Villagers. Six were acquired for the permanent collection of photographs of the Museum of Modern Art.

- 1953 Materials on Friendship and Childhood among Chinese Families in New York. In The Study of Culture at a Distance, Margaret Mead and Rhoda Metraux, eds. Pp. 192–98. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- 1955 Review of SC Dube Indian Village [23]

- 1955 Notes to an Approach to a Study of Personality Formation in a Hindu Village in Gujarat. In Village India: Studies in the Little Community. Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association, No. 83. McKim Marriott, ed. Pp. 102-‐44. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- 1955 Photographs of Indian villagers. Published in The Family of Man, by Edward Steichen. New York: Museum of Modem Art.

- 1964 The Human Career in Village India. Part I: Introduction. Mimeographed copy of draft on file in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York.

- 1968 Devgar. Unpublished screenplay on file with Robert Steed, New York.[24]

- 1967 Photographs. Published as illustrations in Human Action in Four Societies, by Vincent Fresno. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

- 1969 Caste and Kinship in Rural Gujarat: The Social Use of Space. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Ms. in Columbia University Library, New York.

- Steed, Gitel P. n.d. Unpublished papers and field notes. University of Chicago Library.

References

- 1 2 3 Lesser, Alexander 1979 Obituary of Gitel Steed. American Anthropologist 81:88‐91

- ↑ Berleant-Schiller, Riva 1988 Gitel (Gertrude) Poznanski Steed. IN Women Anthropologists: A Biographical Dictionary. Edited by Ute Gacs, Aisha Khan, Jerrie McIntyre, Ruth Weinberg. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. Pp. 331–336. Gitel (Gertrude) Poznanski Steed

- ↑ Kehoe, A. B. (1996). Transcribing Insima, a Blackfoot "Old Lady". Reading beyond words: Native history in context, 381–402.

- ↑ Benedict, Ruth (1934), Patterns of culture, The New American Library, retrieved May 11, 2016

- ↑ Price, D. H. (2008). Anthropological intelligence: the deployment and neglect of American anthropology in the Second World War. Duke University Press.

- ↑ Raphael, D. (1978). More on the Nonacademic Scene. Anthropology News, 19(3), 22–22.

- ↑ Lieberman, L. (1997). Gender and the Deconstruction nf the Race Concept. American Anthropologist, 99(3), 545–588.

- ↑ Margaret Mead and Rhoda Metraux, and published in 1953 by the University of Chicago Press

- ↑ Mandelbaum, David Goodman, 1911–1987; Hockings, Paul (1987), Dimensions of social life : essays in honor of David G. Mandelbaum, Berlin New York M. de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-084685-0

- ↑ Shavit, David (1990), The United States in Asia : a historical dictionary, Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-26788-8

- ↑ When Theodore Abel approved the project, his confidence was supported by commonalities with Steed in relation to Nazism, as in 1934 Abel had traveled to Germany to gather autobiographies of members of the National Socialist movement. The hundreds of essays he received enabled him to theorise about how the Nazis managed to gain and retain power. See his "Why Hitler Came Power", Prentice-Hall, 1938; "Systematic Sociology in Germany", Octagon, 1966; "The Nazi Movement, Atherton", 1967

- 1 2 University of Chicago Library (2009) Guide to the Gitel P. Steed Papers 1907–1980

- ↑ "The real beginning of Projective Psychology in india may be credited to the author with his first exposure with Rorschach test under the guidance of Dr. James Silverberg (1955) who had administered Rorschach Test to the author [Nandlal Dosajh] in 1949 and on the basis of author's performance on this test, he was selected to work with the Columbia University Team under Dr. Gitel P. Steed on the project 'An Approach to a Study of Personality Formation in a Hindu Village in Gujarat' (1955)." Projective Psychology in India Dosajh, N L, PhD. SIS Journal of Projective Psychology & Mental Health 5.2 (Jul 1998): 83–86.

- ↑ Donham, B., & Roethlisberger, J. People and Projects.

- ↑ Eames, E.. (1966). Hindu Cousin Marriages. American Anthropologist, 68(3), 757–758.

- ↑ Arensberg, Conrad 1963 Unpublished letter on file in the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y.

- ↑ Von Fürer-Haimendorf, C.. (1957). [Review of Village India: Studies in the Little Community]. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 19(2), 394–395.

- ↑ " Gitel P. Steed shifts the focus almost com- pletely and illustrates the effects of changes in the traditional view on the personality formation of a single Hindu landlorD" Smith, M. W.. (1956). [Review of Village India: Studies in the Little Community]. The British Journal of Sociology, 7(3), 263–264.

- ↑ Beals, Alan R & Marriott, McKim (1955). Village India : studies in the little community : papers. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- ↑ Opler, M. E.. (1955). [Review of Village India: Studies in the Little Community.]. The Far Eastern Quarterly, 15(1), 146–153.

- ↑ Cappannari, S. C.. (1957). [Review of Village India: Studies in the Little Community]. American Anthropologist, 59(3), 558–559.

- ↑ Museum of Modern Art press release of February 19, 1953, for Always the Young Strangers.

- ↑ Steed, G. P. (1956). Indian Village. By SC Dube. Foreword by Morris E. Opler. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1955. xiv, 248. Glossary, Bibliography, Index. $3.00. The Journal of Asian Studies, 15(04), 620–622.

- ↑ Ivory, James; Long, Robert Emmet (2005), James Ivory in conversation : how Merchant Ivory makes its movies, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-23415-4

Bibliography

- Arensberg, Conrad 1963 Unpublished letter on file in the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y.

- Berleant-Schiller, Riva 1988 Gitel (Gertrude) Poznanski Steed. IN Women Anthropologists: A Biographical Dictionary. Edited by Ute Gacs, Aisha Khan, Jerrie McIntyre, Ruth Weinberg. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 331–336. Gitel (Gertrude) Poznanski Steed

- Bunzel, Ruth 1962 Unpublished letter on file in the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y.

- Contemporary Authors 1972 "Gitel Steed." 1st rev. ed., vol. 41–44, p. 663. Ann Evory, ed. Detroit: Gale Research.

- Lesser, Alexander 1979 Obituary of Gitel Steed. American Anthropologist 81:88-‐91

- New York Times 1977 Obituary of Gitel Steed. September 9.

External links

- The Gitel Steed collection at the University of Chicago Library