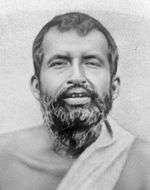

Girish Chandra Ghosh

Girish Chandra Ghosh (28 February 1844 – 8 February 1912) was a Bengali musician, poet, playwright, novelist, theatre director and actor. He was largely responsible for the golden age of Bengali theatre.[1][2][3] He can be referred to as the Father of Bengali Theatre. He was a versatile genius, a scholar without having any formal educational background, an actor of repute and a mentor who brought up many actors and actresses, including Binodini Dasi.

He cofounded the Great National Theatre, the first Bengali professional theatre company in 1872, wrote nearly 40 plays and acted and directed many more,[4] and later in life became a noted disciple of Sri Ramakrishna.[5]

Biography

Early days

Born in Bagbazar, Kolkata, in 1844, the eighth child to his parents Nilkamal and Raimani, he received his early education at Hare School, and later studied at Oriental Seminary in the city. His father Nilkamal Ghosh was a generous and kind hearted person and Girish retained some of his father's large heartedness. He lost his parents early in life and went up to educate himself.

Professional career

Girish was a prominent actor in the Bagbazar Amateur Theatre where he had Ardhendu Mustafi, another great contemporary actor, as his partner. Together they performed in 'Sadhabar Ekadashi' by famous playwright Dinabandhu Mitra which became very popular. Later Bagbazar Amateur was renamed in 1871 as the National Theatre. Girish however left National Theatre and went to form the Great National Theatre in 1873. However he could not run this theatre for long. Later he also worked in Minerva Theatre and went to become a manager in Star Theatre. The maiden show at the Star Theatre was 'Daksha Jagna' by Girish Chandra Ghosh on the auspicious day of 21 July 1883. With Binodini Dasi, he staged his play, Chaitanyalila, at the Star Theatre on 20 September 1884, with, Sri Ramakrishna in the audience. Girish wrote about 86 plays, most of which were based upon stories from Purana, Ramayana and Mahabharata. Among his famous works were Buddhadev Charit, Purna Chandra, Nasiram, Kalapahar, Ashoka, Shankaracharya, Chaitanyalila, Nimai Sannyas, Rup-Sanatan, Vilwamangal, Prahlad Charit. Most of his plays were performed in Star Theatre in Calcutta.[6]

Girish's mind worked so fast and prodigiously that he required secretaries to take down his words. Absorbed in the flow of ideas, he would pace back and forth in his room and dictate all the dialogues of the drama in a loud voice, as if he were acting each role himself. His secretary always kept three pencils ready at hand. He could not use a pen and inkpot because there was never enough time to dip the pen into the pot. Once his secretary Debendra Nath Majumdar could not keep up with the speed of the dictation and asked Girish to repeat what he had just said. Girish became angry and asked him not to break his mood. He told the Debendranath to put dots where he had missed words, and that he would fill them in later. There are many stories about his writing talent. Sitar Vanabash (The Banishment of Sita) was written in one night. He also wrote twenty-six songs for Sadhavar Ekadashi in just one night. Sister Devamata mentioned in Days in an Indian Monastery, 'One of the greatest, a six act drama entitled Vilwamangal the Saint, was written in twenty-eight hours of uninterrupted labour.’

Personal life

Girish came into much grief in his family life and became a staunch atheist till he met Ramakrishna Paramhansa. In his personal life he met with many tragedies, losing both his wives, two daughters, and his younger son whom he loved very dearly, at the age of three. He was a very hard worker in his earlier days. It became common practice for him to work all day at the office then go to the theatre in the evening to act in a play, returning home at three or four o'clock in the morning. But when his first wife Pramodini gave birth to a still born daughter, Girish regretted his negligence of his wife and engaged best doctors for her. However she died leaving a son and a daughter. Girish was 30 years old at that time and this incident hardened his disbelief in God.

Influence of Sri Ramakrishna

Although a notorious libertine, Girish eventually became one of the close disciples of Sri Ramakrishna, the 19th century Bengali saint. The story of Girish's relationship with Sri Ramakrishna, and his eventual transformation into a renunciate who was "second to none" is documented in the Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita later translated into English as "The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna".

Girish first met Sri Ramakrishna in the ancestral home of his neighbour Kalinath Bose. On 21 September 1884 Sri Ramakrishna went to watch Chaitanya Lila in Star Theatre. It is said that Girish's first meeting with Sri Ramakrishna, was not very cordial. He saw Sri Ramakrishna in divine ecstasy and thought it to be some kind of a trick. But later when Ramakrishna met him the Master told him that the incident was no trick and Girish was extremely surprised to find master reading his thought. Later when the Master went to watch his theatre he and Girish repeatedly went on exchanging salutes and ultimately Girish had to give up. Girish later said about this incident that in Iron Age the best weapon is "pranamastra" or the "'salute weapon" with which god kills His enemies. In his play Nasiram, Girish used much of the teachings of Sri Ramakrishna.[7] There are many scenes in The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna involving Girish and Sri Ramakrishna. Sri Ramakrishna went to watch several of his plays in Star Theatre. He also blessed Binodini Dasi, one of the lead actresses.

Relationship with Swami Vivekananda

Girish was very friendly with Swami Vivekananda despite their age difference. They had tremendous respect for each other. Young Naren (Vivekananda) loved watching his plays like Budhha Charit. Swami Vivekananda used to call him "G.C" affectionately. The first meeting of Ramakrishna Mission took place on 1 May 1897 in Balaram Bose's house in which Girish Chandra Ghosh was one of the prominent representatives. He wholeheartedly supported Swamiji's proposal of service for the mankind as one of the mottos of the association in that meeting. When Swami Vivekananda's plan of social commitment for the monks of Ramakrishna order was criticised by many householder and monastic disciples of Sri Ramakrishna as deviation from Sri Ramakrishna's teachings, Girish came out strongly in Swami's defence. In his article "Ramakrishna o Bivekananda" in Bengali (Ramakrishna and Vivekananda), Girish mentioned that "to comprehend Ramakrishna fully, one would have to keep the live model of Vivekananda constantly before one's mind." Girish Ghosh told Sarat Chandra Chakravarti, a direct disciple of Swami Vivekananda, "What a great loving heart he (Vivekananda) has! I don't honour your Swamiji simply for being a Pundit versed in the Vedas; but I honour him for that great heart of his which just made him retire weeping at the sorrows of his fellow beings." During Sri Ramakrishna's Tithipuja in the rented Math premises in Belur, Swami Vivekananda dressed Girish Chandra Ghosh with his own hands as a Bhairava or a divine companion of lord Shiva.

Later years

Girish had unwavering faith not only for Sri Ramakrishna, but also the Holy Mother of the Ramakrishna Order, Sarada Devi. He stayed for a month in Jayrambati, the birthplace of the holy mother while she was staying there and eulogised her as the universal mother in front of a large gathering. He also requested the presence of mother in his Durga Puja, in 1907. The mother, despite her severe illness came to the Durga Puja and received obeisance from thousands of devotees as the embodiment of the goddess Durga.

In films

His novel Bhakta Dhruva was adapted into a film by the poet Kazi Nazrul Islam. He was also the subject of a biographical film, in Bengali, Mahakavi Girish Chandra (1956), directed by Modhu Bose.[8]

Further reading

- From The Undivine Tree to the Divine Fruit: Girish Chandra Ghosh by Sri Chinmoy, 1991. Online

References

- ↑ Drama 1900 -1926 Handbook of twentieth-century literatures of India, by Nalini Natarajan, Emmanuel Sampath Nelson. Published by Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996. ISBN 0313287783. Page 48.

- ↑ Kundu, Pranay K. Development of Stage and Theatre Music in Bengal. Published in Banerjee, Jayasri (ed.), The Music of Bengal. Baroda: Indian Musicological Society, 1987.

- ↑ A Girish Chandra Ghosh History of Indian Literature: 1800–1910 : Western Impact, Indian Response, by Sisir Kumar Das, Sahitya Akademi, Published by Sahitya Akademi. 1991. ISBN 8172010060. Page 283.

- ↑ Girish Chandra Ghosh Britannica.com.

- ↑ Some Great Devotees Ramakrishna and his disciples, by Christopher Isherwood, Ramakrishna Vedanta Centre. Published by Vedanta Press, 1980. ISBN 087481037X. Page 247.

- ↑ Girish Chandra Ghosh Archived 19 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Contemporary Bengali Literature – I, by Hiranmoy Mukherjee, Vedanta Kesari, April 2010

- ↑ Mahakavi Girish Chandra at the Internet Movie Database

- Girish Chandra Ghosh, by Utpal Dutta. Published by Sahitya Akademi, 1992. ISBN 8172011970. Online

"Girish Chandra Ghosh", by Swami Chetanananda, Copyright 2009 Vedanta Society of St. Louis, ISBN 978-0-916356-92-7, www.vedantastl.org