Gibbs free energy

| Thermodynamics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

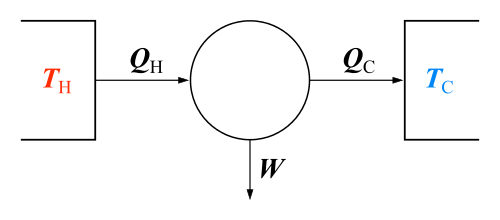

The classical Carnot heat engine | ||||||||||||

|

Branches |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Book:Thermodynamics | ||||||||||||

In thermodynamics, the Gibbs free energy (IUPAC recommended name: Gibbs energy or Gibbs function; also known as free enthalpy[1] to distinguish it from Helmholtz free energy) is a thermodynamic potential that can be used to calculate the maximum or reversible work that may be performed by a thermodynamic system at a constant temperature and pressure (isothermal, isobaric). Just as in mechanics, where the decrease in potential energy is defined as maximum useful work that can be performed, similarly different potentials have different meanings. The decrease in Gibbs free energy (kJ in SI units) is the maximum amount of non-expansion work that can be extracted from a thermodynamically closed system (one that can exchange heat and work with its surroundings, but not matter); this maximum can be attained only in a completely reversible process. When a system transforms reversibly from an initial state to a final state, the decrease in Gibbs free energy equals the work done by the system to its surroundings, minus the work of the pressure forces.[2]

The Gibbs energy (also referred to as G) is also the thermodynamic potential that is minimized when a system reaches chemical equilibrium at constant pressure and temperature. Its derivative with respect to the reaction coordinate of the system vanishes at the equilibrium point. As such, a reduction in G is a necessary condition for the spontaneity of processes at constant pressure and temperature.

The Gibbs free energy, originally called available energy, was developed in the 1870s by the American scientist Josiah Willard Gibbs. In 1873, Gibbs described this "available energy" as

the greatest amount of mechanical work which can be obtained from a given quantity of a certain substance in a given initial state, without increasing its total volume or allowing heat to pass to or from external bodies, except such as at the close of the processes are left in their initial condition.[3]

The initial state of the body, according to Gibbs, is supposed to be such that "the body can be made to pass from it to states of dissipated energy by reversible processes." In his 1876 magnum opus On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances, a graphical analysis of multi-phase chemical systems, he engaged his thoughts on chemical free energy in full.

Overview

According to the second law of thermodynamics, for systems reacting at STP (or any other fixed temperature and pressure), there is a general natural tendency to achieve a minimum of the Gibbs free energy.

A quantitative measure of the favorability of a given reaction at constant temperature and pressure is the change ΔG in Gibbs free energy that is (or would be) caused by the reaction. As a necessary condition for the reaction to occur at constant temperature and pressure, ΔG must be smaller than the non-PV (e.g. electrical) work, which is often equal to zero. ΔG equals the maximum amount of non-PV work that can be performed as a result of the chemical reaction for the case of reversible process. If the analysis indicated a positive ΔG for the reaction, then energy —in the form of electrical or other non-PV work— would have to be added to the reacting system for ΔG to be smaller than the non-PV work and make it possible for the reaction to occur.[4]:298–299

The equation can be also seen from the perspective of the system taken together with its surroundings (the rest of the universe). First assume that the given reaction at constant temperature and pressure is the only one that is occurring. Then the entropy released or absorbed by the system equals the entropy that the environment must absorb or release, respectively. The reaction will only be allowed if the total entropy change of the universe is zero or positive. This is reflected in a negative ΔG, and the reaction is called exergonic.

If we couple reactions, then an otherwise endergonic chemical reaction (one with positive ΔG) can be made to happen. The input of heat into an inherently endergonic reaction, such as the elimination of cyclohexanol to cyclohexene, can be seen as coupling an unfavourable reaction (elimination) to a favourable one (burning of coal or other provision of heat) such that the total entropy change of the universe is greater than or equal to zero, making the total Gibbs free energy difference of the coupled reactions negative.

In traditional use, the term "free" was included in "Gibbs free energy" to mean "available in the form of useful work."[2] The characterization becomes more precise if we add the qualification that it is the energy available for non-volume work.[5] (An analogous, but slightly different, meaning of "free" applies in conjunction with the Helmholtz free energy, for systems at constant temperature). However, an increasing number of books and journal articles do not include the attachment "free", referring to G as simply "Gibbs energy". This is the result of a 1988 IUPAC meeting to set unified terminologies for the international scientific community, in which the adjective ‘free’ was supposedly banished.[6][7][8] This standard, however, has not yet been universally adopted.

History

The quantity called "free energy" is a more advanced and accurate replacement for the outdated term affinity, which was used by chemists in the earlier years of physical chemistry to describe the force that caused chemical reactions.

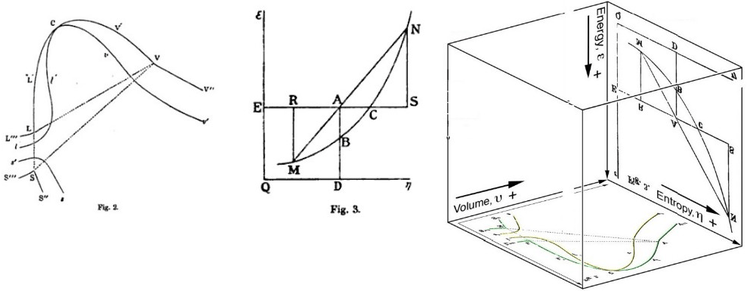

In 1873, Willard Gibbs published A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces, in which he sketched the principles of his new equation that was able to predict or estimate the tendencies of various natural processes to ensue when bodies or systems are brought into contact. By studying the interactions of homogeneous substances in contact, i.e., bodies composed of part solid, part liquid, and part vapor, and by using a three-dimensional volume-entropy-internal energy graph, Gibbs was able to determine three states of equilibrium, i.e., "necessarily stable", "neutral", and "unstable", and whether or not changes would ensue. Further, Gibbs stated:[9]

In this description, as used by Gibbs, ε refers to the internal energy of the body, η refers to the entropy of the body, and ν is the volume of the body.

Thereafter, in 1882, the German scientist Hermann von Helmholtz characterized the affinity as the largest quantity of work which can be gained when the reaction is carried out in a reversible manner, e.g., electrical work in a reversible cell. The maximum work is thus regarded as the diminution of the free, or available, energy of the system (Gibbs free energy G at T = constant, P = constant or Helmholtz free energy F at T = constant, V = constant), whilst the heat given out is usually a measure of the diminution of the total energy of the system (internal energy). Thus, G or F is the amount of energy "free" for work under the given conditions.

Until this point, the general view had been such that: "all chemical reactions drive the system to a state of equilibrium in which the affinities of the reactions vanish". Over the next 60 years, the term affinity came to be replaced with the term free energy. According to chemistry historian Henry Leicester, the influential 1923 textbook Thermodynamics and the Free Energy of Chemical Substances by Gilbert N. Lewis and Merle Randall led to the replacement of the term "affinity" by the term "free energy" in much of the English-speaking world.[10]:206

Graphical interpretation

Gibbs free energy was originally defined graphically. In 1873, American scientist Willard Gibbs published his first thermodynamics paper, "Graphical Methods in the Thermodynamics of Fluids", in which Gibbs used the two coordinates of the entropy and volume to represent the state of the body. In his second follow-up paper, "A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces", published later that year, Gibbs added in the third coordinate of the energy of the body, defined on three figures. In 1874, Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell used Gibbs' figures to make a 3D energy-entropy-volume thermodynamic surface of a fictitious water-like substance.[11] Thus, in order to understand the very difficult concept of Gibbs free energy one must be able to understand its interpretation as Gibbs defined originally by section AB on his figure 3 and as Maxwell sculpted that section on his 3D surface figure.

Definitions

The Gibbs free energy is defined as:

which is the same as:

where:

- U is the internal energy (SI unit: joule)

- p is pressure (SI unit: pascal)

- V is volume (SI unit: m3)

- T is the temperature (SI unit: kelvin)

- S is the entropy (SI unit: joule per kelvin)

- H is the enthalpy (SI unit: joule)

The expression for the infinitesimal reversible change in the Gibbs free energy as a function of its 'natural variables' p and T, for an open system, subjected to the operation of external forces (for instance electrical or magnetic) Xi, which cause the external parameters of the system ai to change by an amount dai, can be derived as follows from the First Law for reversible processes:

where:

- μi is the chemical potential of the ith chemical component. (SI unit: joules per particle[12] or joules per mole[2])

- Ni is the number of particles (or number of moles) composing the ith chemical component.

This is one form of Gibbs fundamental equation.[13] In the infinitesimal expression, the term involving the chemical potential accounts for changes in Gibbs free energy resulting from an influx or outflux of particles. In other words, it holds for an open system. For a closed system, this term may be dropped.

Any number of extra terms may be added, depending on the particular system being considered. Aside from mechanical work, a system may, in addition, perform numerous other types of work. For example, in the infinitesimal expression, the contractile work energy associated with a thermodynamic system that is a contractile fiber that shortens by an amount −dl under a force f would result in a term f dl being added. If a quantity of charge −de is acquired by a system at an electrical potential Ψ, the electrical work associated with this is −Ψde, which would be included in the infinitesimal expression. Other work terms are added on per system requirements.[14]

Each quantity in the equations above can be divided by the amount of substance, measured in moles, to form molar Gibbs free energy. The Gibbs free energy is one of the most important thermodynamic functions for the characterization of a system. It is a factor in determining outcomes such as the voltage of an electrochemical cell, and the equilibrium constant for a reversible reaction. In isothermal, isobaric systems, Gibbs free energy can be thought of as a "dynamic" quantity, in that it is a representative measure of the competing effects of the enthalpic and entropic driving forces involved in a thermodynamic process.

The temperature dependence of the Gibbs energy for an ideal gas is given by the Gibbs–Helmholtz equation and its pressure dependence is given by:

if the volume is known rather than pressure then it becomes:

or more conveniently as its chemical potential:

In non-ideal systems, fugacity comes into play.

Derivation

The Gibbs free energy total differential natural variables may be derived via Legendre transforms of the internal energy.

- .

The definition of G from above is

- .

Taking the total differential, we have

- .

Replacing dU with the result from the first law gives[15]

- .

The natural variables of G are then p, T, and {Ni}.

Homogeneous systems

Because S, V, and Ni are extensive variables, an Euler integral allows easy integration of dU:[15]

- .

Because some of the natural variables of G are intensive, dG may not be integrated using Euler integrals as is the case with internal energy. However, simply substituting the above integrated result for U into the definition of G gives a standard expression for G:[15]

- .

This result applies to homogeneous, macroscopic systems, but not to all thermodynamic systems.[16]

Gibbs free energy of reactions

To derive the Gibbs free energy equation for an isolated system, let Stot be the total entropy of the isolated system, that is, a system that cannot exchange energy(heat and work) or mass with its surroundings. According to the second law of thermodynamics:

and if ΔStot = 0 then the process is reversible. The heat transfer Q vanishes for an adiabatic system. Any adiabatic process that is also reversible is called an isentropic process.

Now consider a subsystem having internal entropy Sint. Such a system is thermally connected to its surroundings, which have entropy Sext. The entropy form of the second law applies only to the closed system formed by both the system and its surroundings. Therefore, a process is possible only if

- .

If Q is the heat transferred to the system from the surroundings, then −Q is the heat lost by the surroundings, so that corresponds to the entropy change of the surroundings.

We now have:

Multiplying both sides by T:

Q is the heat transferred to the system; if the process is now assumed to be isobaric, then Q = ΔH:

ΔH is the enthalpy change of reaction (for a chemical reaction at constant pressure). Then:

for a possible process. Let the change ΔG in Gibbs free energy be defined as

- (eq.1)

Notice that it is not defined in terms of any external state functions, such as ΔSext or ΔStot. Then the second law, which also tells us about the spontaneity of the reaction, becomes:

- favoured reaction (Spontaneous)

- Neither the forward nor the reverse reaction prevails (Equilibrium)

- disfavoured reaction (Nonspontaneous)

Gibbs free energy G itself is defined as

- (eq.2)

but notice that to obtain equation (1) from equation (2) we must assume that T is constant. Thus, Gibbs free energy is most useful for thermochemical processes at constant temperature and pressure: both isothermal and isobaric. Such processes don't move on a P-T diagram, such as phase change of a pure substance, which takes place at the saturation pressure and temperature. Chemical reactions, however, do undergo changes in chemical potential, which is a state function. Thus, thermodynamic processes are not confined to the two dimensional P-V diagram. There is an additional dimension for the extent of the chemical reaction, associated with the changes of the amounts of the substances in the system. For the study of explosive chemicals, the processes are not necessarily isothermal and isobaric. For these studies, Helmholtz free energy is used.

If an isolated system (Q = 0) is at constant pressure (Q = ΔH), then

Therefore, the Gibbs free energy of an isolated system is

and if ΔG ≤ 0 then this implies that ΔS ≥ 0, back to where we started the derivation of ΔG.

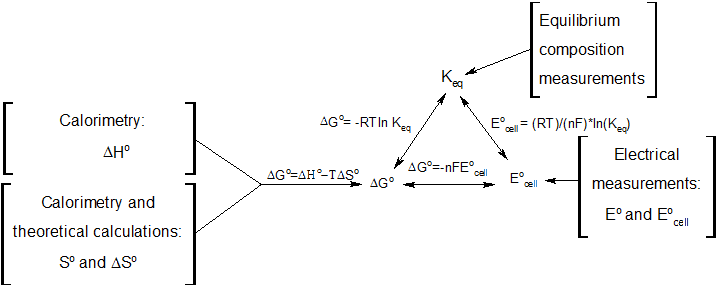

Useful identities to derive the Nernst equation

During a reversible electrochemical reaction at constant temperature and pressure, the following equations involving the Gibbs free energy hold:

- (see chemical equilibrium)

- (for a system at chemical equilibrium)

- (for a reversible electrochemical process at constant temperature and pressure)

- (definition of E°)

and rearranging gives

which relates the cell potential resulting from the reaction to the equilibrium constant and reaction quotient for that reaction (Nernst equation).

where

- ΔrG = Gibbs free energy change per mole of reaction

- ΔrG° = Gibbs free energy change per mole of reaction for unmixed reactants and products at standard conditions

- R = gas constant

- T = absolute temperature (in K)

- ln = natural logarithm

- Qr = reaction quotient (unitless)

- K = equilibrium constant (unitless)

- welec,rev = electrical work in a reversible process (chemistry sign convention)

- n = number of moles of electrons transferred in the reaction

- F = Faraday constant = 96485 C/mol (charge per mole of electrons)

- E = cell potential (in V)

- E° = standard cell potential (in V)

Moreover, we also have:

which relates the equilibrium constant with Gibbs free energy.

Gibbs free energy, the second law of thermodynamics, and metabolism

A chemical reaction will (or can) proceed spontaneously if the change in the total entropy of the universe that would be caused by the reaction is nonnegative. As discussed in the overview, if the temperature and pressure are held constant, the Gibbs free energy is a (negative) proxy for the change in total entropy of the universe. It is "negative" because S appears with a negative coefficient in the expression for G, so the Gibbs free energy moves in the opposite direction from the total entropy. Thus, a reaction with a positive Gibbs free energy will not proceed spontaneously. However, in biological systems (among others), energy inputs from other energy sources (including the sun and exothermic chemical reactions) are "coupled" with reactions that are not entropically favored (i.e. have a Gibbs free energy above zero). Taking into account the coupled reactions, the total entropy in the universe increases. This coupling allows endergonic reactions, such as photosynthesis and DNA synthesis, to proceed without decreasing the total entropy of the universe. Thus biological systems do not violate the second law of thermodynamics.

Standard energy change of formation

The standard Gibbs free energy of formation of a compound is the change of Gibbs free energy that accompanies the formation of 1 mole of that substance from its component elements, at their standard states (the most stable form of the element at 25 degrees Celsius and 100 kilopascals). Its symbol is ΔfG˚.

All elements in their standard states (diatomic oxygen gas, graphite, etc.) have standard Gibbs free energy change of formation equal to zero, as there is no change involved.

- ΔfG = ΔfG˚ + RT ln Qf ; Qf is the reaction quotient.

At equilibrium, ΔfG = 0 and Qf = K so the equation becomes ΔfG˚ = −RT ln K; K is the equilibrium constant.

Table of selected substances[17]

| Substance | State | ΔfG°(kJ/mol) | ΔfG°(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO | g | 87.6 | 20.9 |

| NO2 | g | 51.3 | 12.3 |

| N2O | g | 103.7 | 24.78 |

| H2O | g | -228.6 | −54.64 |

| H2O | l | -237.1 | −56.67 |

| CO2 | g | -394.4 | −94.26 |

| CO | g | -137.2 | −32.79 |

| CH4 | g | -50.5 | −12.1 |

| C2H6 | g | -32.0 | −7.65 |

| C3H8 | g | -23.4 | −5.59 |

| C6H6 | g | 129.7 | 29.76 |

| C6H6 | l | 124.5 | 31.00 |

See also

- Calphad

- Electron equivalent

- Enthalpy-entropy compensation

- Free entropy

- Grand potential

- Thermodynamic free energy

Notes and references

- ↑ Greiner, Walter; Neise, Ludwig; Stöcker, Horst (1995). Thermodynamics and statistical mechanics. Springer-Verlag. p. 101.

- 1 2 3 Perrot, Pierre (1998). A to Z of Thermodynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856552-6.

- ↑ J.W. Gibbs, "A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces," Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 2, Dec. 1873, pp. 382-404 (quotation on p. 400).

- ↑ Peter Atkins; Loretta Jones (1 August 2007). Chemical Principles: The Quest for Insight. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1-4292-0965-6.

- ↑ Reiss, Howard (1965). Methods of Thermodynamics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-69445-3.

- ↑ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Commission on Atmospheric Chemistry, J. G. (1990). "Glossary of Atmospheric Chemistry Terms (Recommendations 1990)". Pure Appl. Chem. 62 (11): 2167–2219. doi:10.1351/pac199062112167. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ↑ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Commission on Physicochemical Symbols Terminology and Units (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry (2nd Edition). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. p. 251. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ↑ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Commission on Quantities and Units in Clinical Chemistry, H. P.; International Federation of Clinical Chemistry Laboratory Medicine Committee on Quantities and Units (1996). "Glossary of Terms in Quantities and Units in Clinical Chemistry (IUPAC-IFCC Recommendations 1996)". Pure Appl. Chem. 68 (4): 957–1000. doi:10.1351/pac199668040957. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ↑ J.W. Gibbs, "A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces," Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 2, Dec. 1873, pp. 382-404 .

- ↑ Henry Marshall Leicester (1971). The Historical Background of Chemistry. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-61053-5.

- ↑ James Clerk Maxwell, Elizabeth Garber, Stephen G. Brush, and C. W. Francis Everitt (1995), Maxwell on heat and statistical mechanics: on "avoiding all personal enquiries" of molecules, Lehigh University Press, ISBN 0-934223-34-3, p. 248.

- ↑ Chemical Potential - IUPAC Gold Book

- ↑ Müller, Ingo (2007). A History of Thermodynamics - the Doctrine of Energy and Entropy. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-46226-2.

- ↑ Katchalsky, A.; Curran, Peter F. (1965). Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics in Biophysics. Harvard University Press. CCN 65-22045.

- 1 2 3 Salzman, William R. (2001-08-21). "Open Systems". Chemical Thermodynamics. University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 2007-07-07. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ Brachman, M. K. (1954). "Fermi Level, Chemical Potential, and Gibbs Free Energy". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 22 (6): 1152–1151. Bibcode:1954JChPh..22.1152B. doi:10.1063/1.1740312.

- ↑ CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 2009, pp. 5-4 - 5-42, 90th ed., Lide

External links

- IUPAC definition (Gibbs energy)

- Gibbs free energy calculator

- Gibbs energy - Florida State University

- Gibbs Free Energy - Eric Weissteins World of Physics

- Entropy and Gibbs Free Energy - www.2ndlaw.oxy.edu

- Gibbs Free Energy - Georgia State University

- Gibbs Free Energy Java Applet - University of California, Berkeley

- Using Gibbs Free Energy for prediction of chemical driven material ageing